Silk and Milk

Tessa Silva’s Smock collection pays homage to historically gendered labour practices by using hand-pleated fabric, as well as techniques and materials typically found in kitchens (image: Benedict Brink).

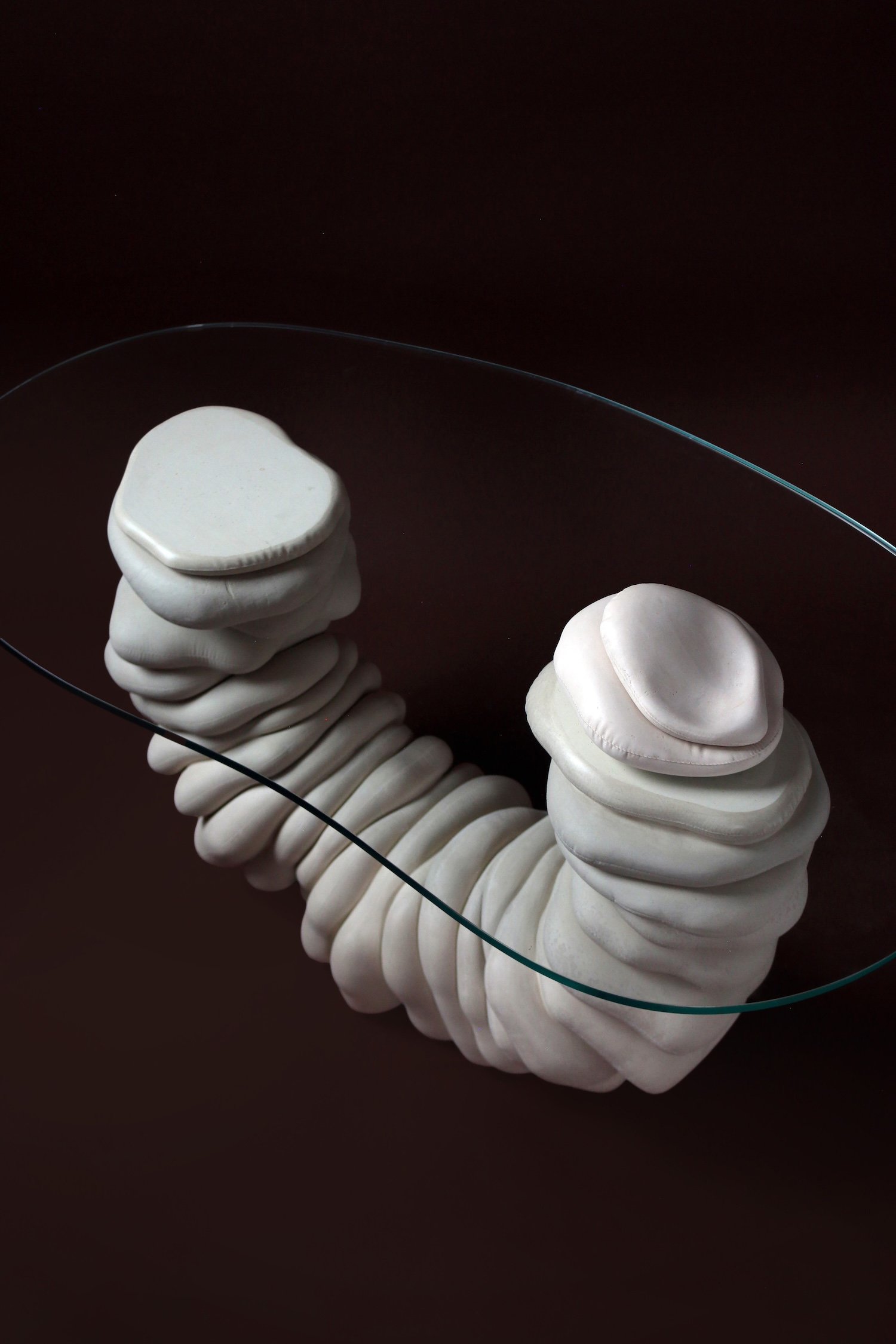

Artist and designer Tessa Silva’s Feminised Protein collection has the doughy look of unbaked clay. Made from milk curds mixed with chalk, each sculpture and piece of furniture bears the shadows of the fabric moulds the material was cast from, with the edges of their forms puckering at the seams like pillowcases. Her latest series Smock, however, shines a light on fabric – in the place of a ghostly imprint, the textile has now been used to create hand-pleated stools and vases whose shapes are as organic and bodily as her previous work.

Silva first came across the idea of working with milk after reading about a Tudor floor made from milk and chalk while researching pre-industrial materials. “During my Masters at the Royal College of Art, we were all being pushed to carve out a niche for ourselves, and everyone wanted to be working with something different,” Silva says. “I kind of got in a bit too deep, you know – I’ve been pretty much solely working with milk for the last 10 years.” Inspired by architectural fabric forming, which is typically used to cast concrete into curved shapes, Silva taught herself to sew fabric moulds to use with milk. “I was spending all this time sourcing deadstock fabric, and I wanted to develop my sewing skills,” she says, explaining the transition towards creating pleated furniture and homeware. “I wanted to take a skill that I taught myself for this quite utilitarian purpose, and then transform it into a whole new project.”

For her previous collection, Feminised Protein, Silva made sculptures and furniture out of milk and chalk, which were cast into organic shapes using fabric moulds (image: Tessa Silva).

Beyond the use of fabric, the two projects share similar techniques. “With the vases, I make a mould of pleated fabric and then I inflate them with a mixture of sand and a sugar-based hardening agent,” she explains. The mixture has the consistency of papier-mâché, and in order to transfer it into the pleated fabric Silva uses a sausage stuffer – the same piece of equipment she used to transfer the milk material into fabric moulds in her previous work. “The fabric literally blows up like a balloon, all the sand gets into all the little creases and crevices and expands it,” she describes, explaining that the mixture later hardens into a sturdy material. “I don’t know where I got the idea for that recipe,” Silva says, “but I’m quite used to using kitchen materials and things that are used in food.” When Silva began turning her milk and chalk sculptures into utilitarian objects such as tables, she even sourced a protective varnish made from milk whey. “I didn’t want to use resin varnish because then it kind of defeats the point of it being a natural material,” she explains, adding that she uses natural fibres such as silk, cotton and wool for her Smock project.

The Smock vases are made from hand-pleated fabric which is inflated using a mixture of sand and a sugar-based hardening agent (image: Benedict Brink).

While the vases are made from hard curves of fabric that resemble piped icing, the stools have pleats that are irregularly stuffed with loose wool, with some appearing wide and voluminous while others are neat pin-tucks. The thin pleats cinch the stool’s form, creating structural lines that act as waists and hipbones, while the wide pleats drape off the stool like bellies, the fabric oozing between each stitch as though exhaling after unbuttoning a pair of jeans. “I find it really hard to use bold colours because I’ve been working with white for so long,” Silva says, explaining that she typically uses earthy or spring-like colours, although she has experimented with one hot pink vase whose colour accentuates the cake-like quality of its fabrication. “My friend is an image researcher and she gathered images from runways, and archival imagery like old cartoons and illustrations, and I zoomed in and cropped little bits of the image collection that I thought worked well and brought them to the fabric shop,” she says.

The stools are made from hand-pleated fabric which has been irregularly stuffed with loose wool to create bodily shapes (image: Benedict Brink).

The stool’s seats are typically upholstered in a contrasting colour – light pink against dark red pleats, for example, or bright orange against brown – and the pleated fabric hugs the stool’s frame like an evening gown midway through being rolled off someone’s body. “I think maybe, subconsciously, it’s a bit of a celebration of female forms, which has also come from years of developing the milk material which was tied to female mammals,” she explains, alluding to her previous furniture and sculptures made from shapes that resembled fat rolls. Both the milk-derived material and its soft forms aimed to make visible the acts of creation, sustenance and care which non-human animals contribute to society. “It doesn’t really make sense to cast a very straight edged, right angled piece from a material which is liquid, and which came from an animal,” she says. “The same applies to the fabric as well – the material kind of dictates and guides what we do with it, and it feels like it wants to be used in a more organic way.”

While Feminised Protein drew comparisons between the visceral realities of dairy production and the societal structures that obscure and devalue women’s contributions, Smock continues this focus on gendered labour by invoking the history of sewing. “Women did a lot of the work to do with fabric and mending, and they would use stitching as a way to record their experiences and pass down stories,” Silva explains, adding that sewing has often been used to pass along covert information or as a form of protest. “My grandma’s family emigrated from Lebanon to Brazil, and she was a professional knitter and embroiderer there and would use embroidering as a really therapeutic way of recording her stories and teaching them to her daughters.” Silva sees her focus on labour as something which connects her to women in her family and throughout history. “There’s this softness to my work that I don’t think should be seen as a vulnerability or weakness,” she says. Silva’s stools, after all, are made from more than 3,000 stitches each, and despite its malleable appearance, her milk material hardens into the consistency of stone. “It’s more about connecting with the ways in which women have made and worked.”

Words Helen Gonzalez Brown