Factory Diaries

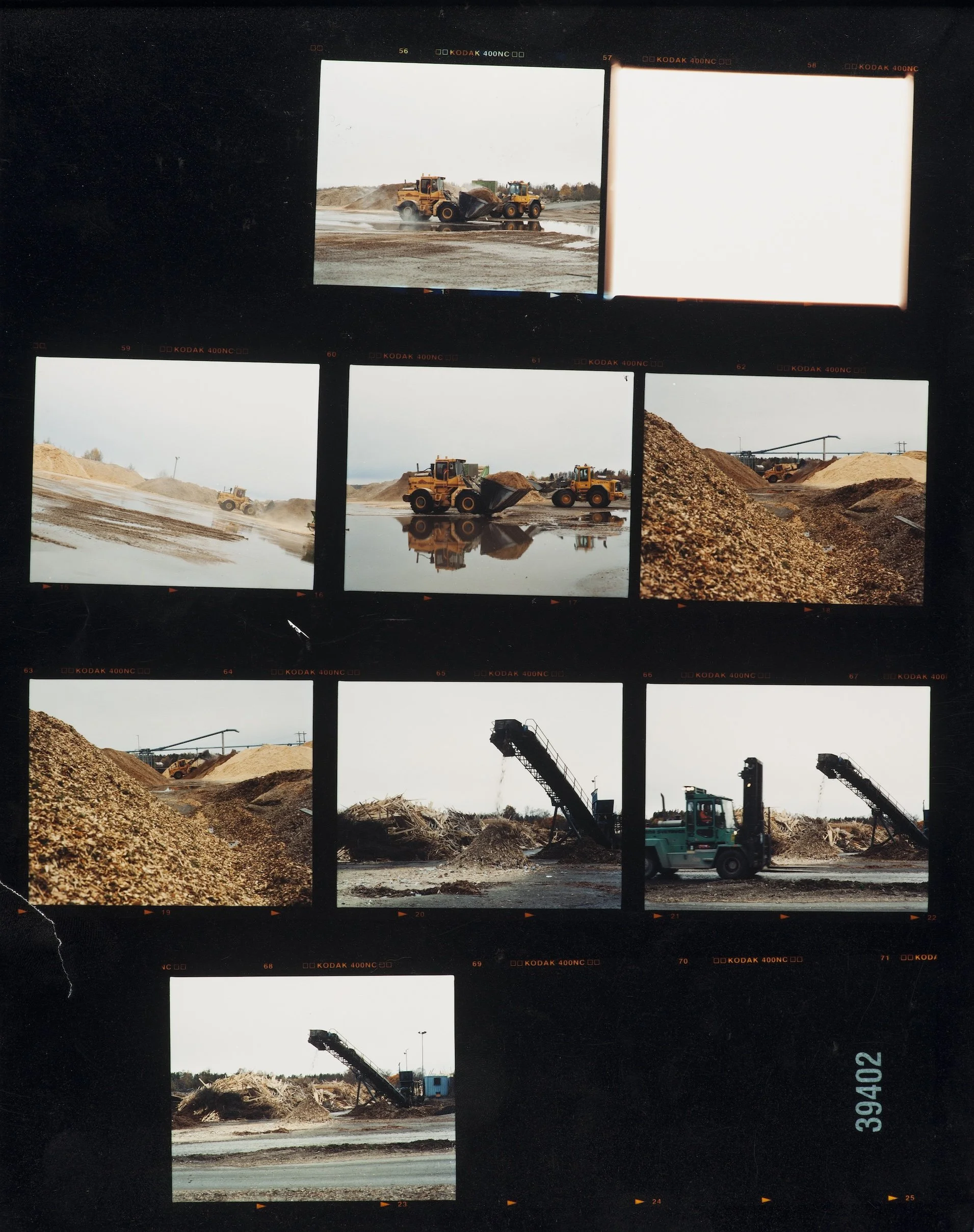

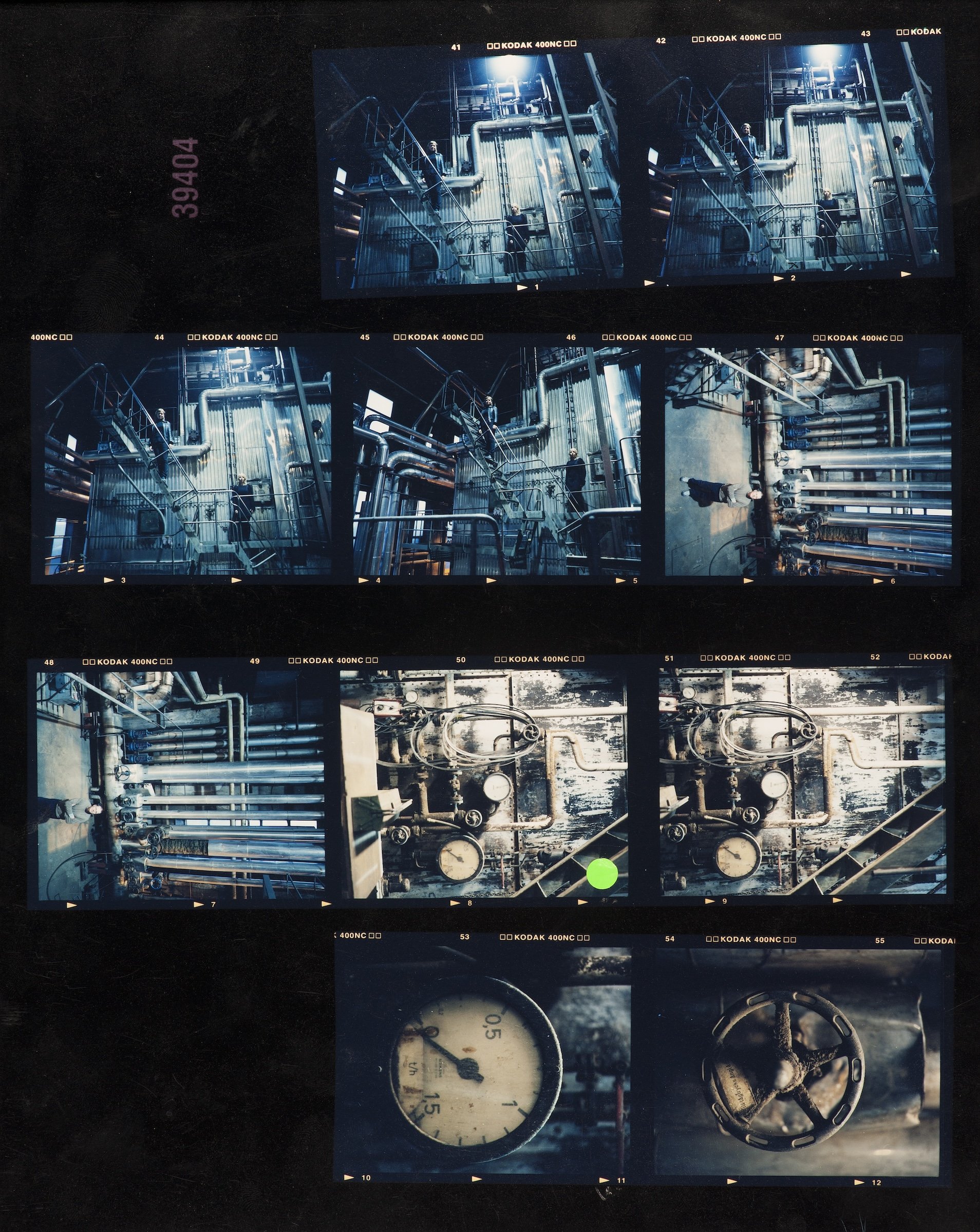

Folkform’s ode to the last Masonite factory in Sweden documents the design studio’s first visits to the rumbling factory up to its eventual closure (image: Magnus Laupa).

“We see a potential for design to create a narrative that visualises the production process and material,” writes designer Anna Holmquist in her 2023 PhD thesis ProduktionsNoveller, newly published by Konst/ig Books. “This points towards a new designer role inspired by craft – a designer working close to production to highlight old manufacturing techniques and make the industrial heritage visible.”

For the past 20 years Holmquist and her design partner Chandra Ahlsell, who together founded the Stockholm-based design practice Folkform in 2005, have been experimenting with Masonite. Invented in America in 1924, and soon highly popular in Sweden, Masonite is a hardwood material formed from a sawdust and wood fibre pulp that is subjected to intense steam and heat, before being compressed and formed into final shape as a board.

“The areas of use for the material seemed limitless during [the early 20th century],” Holmquist explains. “[The] wooden hardboard was used [for] everything from building temporary pavilions and kiosks to more permanent buildings such as garages and a surface material in interiors, especially kitchens.[…] In Sweden, Masonite was used as insulation panels during the winter and for small cabins where the family could spend their holiday during summer. The Masonite hardboard was part of the construction of the Swedish Welfare State and became a symbol of the period’s belief in the future.”

By the second half of the 20th century, however, Masonite’s status had fallen, with the material no longer carrying the sense of progressiveness that it once did. Today, Masonite is mostly used as a cheap construction material for theatre sets, skateboard ramps, and artists’ canvases, yet Folkform saw potential in the material and its past. Beginning in 2004, they began regularly visiting Sweden’s first Masonite factory in Rundvik, a town in Västerbotten County, northern Sweden, with which they had been invited to collaborate. “How could we renew this material, which had been forgotten since the 1950s,” Holmquist writes, “and make people look at it with new eyes?”

In part, the studio sought to use Masonite as a vehicle to explore the collective amnesia surrounding industrial processes that has grown up in the Global North. “In a time where many of the products we consume are imported from countries where labour is cheap and production is anonymous and impossible for the consumer to trace,” writes Holmquist, “the sincere and transparent story of a product’s origins is more important than ever.” As part of this, they began to reinterpret the material and its production through new design techniques, creating experimental Masonite cabinets and drawers, embedded with pressed flowers and butterflies.

The factory in Rundvik closed in 2011, the last of Sweden’s Masonite factories to do so, and its machinery has since been transported to manufacturers in Thailand. Yet throughout the factory’s last years, and even after its closure, Holmquist and Ahlsell repeatedly visited the facility, with Holmquist documenting all their experiences in ProduktionsNoveller. Throughout this process, their work has been guided by the ideas of philosopher Vilém Flusser, whose 1991 essay ‘The Factory’ argued that “anybody who wants to know about our past should concentrate on excavating the ruins of factories. Anybody who wants to know about our present should concentrate on examining present-day factories critically. And anybody who addresses the issue of our future should raise the question of the factory of the future.”

In what follows, Disegno presents a curated timeline of Folkform’s journey through the Rundvik factory, drawn from excerpts in ProduktionsNoveller. From the studio’s arrival in the factory in 2004, to its return in 2019 when it was already desolate, Holmquist’s memories reveal both Masonite’s manufacturing process and the human stories behind the material. To immerse oneself in these fragmentary memories is to step into Folkform’s practice: to experience the rhythm of the humming steam press, the scent of raw materials, and the connections forged between designer and production method. These are paired with imagery from photographer Magnus Laupa, which is rich with nostalgia. To critic and writer John Berger, “the thrill found in a photograph comes from the onrush of memory,” which is exactly how Holmquist utilises Laupa’s imagery. “I use images to remember,” she explains, “to notice the details, and to communicate with other readers and practitioners.”

2005 The first time we visited the factory in Rundvik was an early winter morning in 2005, when Jan Persson, the head of the factory’s laboratory, collected us from the airport. After what seemed like an eternity in his blue Volvo on a country road lined with dark forests, we drew closer to the factory. We were completely taken aback – it felt as if time had stood still since it was built in 1929.

Steaming wood pulp filled the space with its odour, while the loud noise of the machines was persistent, almost frightening. The heat was overwhelming. Jan showed us the large steam press that compressed the Masonite. He showed us the machine hall, where hundreds of gears and engine parts lay spread across the floor. We said a quick hello to the factory employees, who were sat in a circle having their coffee break.

That first visit to the factory made a deep impact on us. We realised that this was a unique opportunity and that we were about to work with a material that represented a living story of the 20th century. This project would be an experiment in design process just as much as in material innovation.

2005 We proposed to change the surface of the material by blending it with new organic materials, such as flowers, embedding them within the wood pulp. Our aim was to challenge the composition of the Masonite and change its surface to give this humble material a completely new expression.

By changing the surface we attempted to make this everyday, often hidden, material more visible – to give these boards new life and meaning. During the 1930s, just after Masonite was invented, there had been different board patterns and reliefs, but none are still in production today. The idea to add flowers to create natural ornament was completely new.

Folkform’s Masonite Chair, made through a 2021 collaboration with Åke Axelsson (image: Folkform).

2005 Our initial experiments were conducted at night, whilst the production line was not running. Jan carried out all of these first tests with rose petals in secret and it turned out that our idea worked. The colour of the roses, however, disappeared and we ended up with an effect that looked like wilted leaves.

We climbed up the side of the production line where the Masonite hardboards were manufactured and began to scatter flowers to form the patterns that we wanted. We had three minutes at our disposal – regular production had needed to come to a halt on behalf of our flower experiments. With fear-tinged delight, we found ourselves in the middle of mass production – in the heat, the rumbling noise, and the humidity from the press.

2005 The 32 dead butterflies were slowly merging with the hardboard in the press. The patterns of the thin butterfly wings became one with the raw surface of the material. The expression of the traditional material was imbued with new meaning before being placed in the steam press.

2005 We received so many requests that we had to stop buying flowers in Stockholm and instead initiate collaborations with various gardens in Västerbotten. They could deliver sacks full of herbs directly to the factory so that we could make our hardboards on a larger scale. When the first sack of thyme arrived early one spring morning, the staff at the factory entrance thought that the delivery had ended up in the wrong place. They ardently argued, “This is a Masonite factory, not a restaurant.”

2011 When the factory was still operational it was surrounded by 10m-high mountains of woodchips from the surrounding sawmills: the waste that the boards were made of. This cheap, local raw material from the great forests of Norrland was the fundamental element in the manufacturing of Masonite hardboard.

2011 It has now been nearly seven years since we laid down the first flowers. In May, the whole factory will be transported to Thailand. The Norwegian owners have sold the wood processing to Metroply in Thailand and the machines from Rundvik are to be reassembled at a new facility near the Cambodian border. In Thailand, Nordic pine will be replaced with eucalyptus as the chosen raw material.

2019 Jan welcomed us with a smile. He still lived in Rundvik, even though the factory had closed. Now he worked as a consultant with his own company. Jan had been allowed to borrow the factory’s key from the bankruptcy trustee and he opened the gate to let us in. It echoed in the now quiet industrial premises as we walked around. We were both sad and curious, devoutly moving between the halls.

Among abandoned tools and leftover machine parts lie bulging remnants of Masonite. We were still surrounded by the brick shell that once contained a lively production. The ceiling was high and the morning sun shone through large dusty windows. The dismantled machines had left jagged edges in the building. We passed the place where the huge, haunting Masonite press had once been placed. Now there was a square void several meters high, which cut through the room in several planes.

2019 It was the compact silence that made the biggest impression on us. The rumbling machines had fallen silent. The steam that had previously filled the room had been replaced by dry, dusty air. Maybe it was our imagination, but we could sometimes smell a faint scent of Masonite.

2019 Nils-Olof Engstrom, a former mechanic in the factory, had a dark blue work jacket and was by himself when he met us at the factory on that warm June day in 2019. When he took the jacket off, his fair skin and muscular arms became visible. He seemed a little uncomfortable at first, but then extended his upper arm and showed us a large tattoo representing the Masonite logo, or “Masonite Guy” as it was called by most of the factory.

He walked into one of the smaller rooms in the factory and we followed him in. There, deep inside, something green loomed in the middle of all the grey. It was a fragile fern that had started to grow in one corner. Nature had slowly begun to re-enter the site.

Nils-Olof still lived near the factory, as did most of the others who had worked here. He was the fourth generation to have worked at the Masonite factory, which his great-grandfather and grandfather had helped build over 100 years ago. As a child, he had accompanied his grandfather and, even then, Nils-Olof knew that he wanted to work here. “It was my dream job,” he told us.

2019 We spent the night in Rundvik. Jan and his wife had invited us to dinner, and we slept in their guest room on the top floor of the house. The next day we left Rundvik, the factory and its chip piles. Perhaps for the last time?

Introduction Albie Fay

Words Anna Holmquist

Images Magnus Laupa