Do Androids Dream of Acid House?

Sound designer Yuri Suzuki trained Google’s Music LM to reflect the essence of acid house and create his new album, Acid AI (image: courtesy of Yuri Suzuki).

Without a tailwind or extra molecules, my body’s bpm is about 120. Provided the surface is good, it still dances well at lower speeds, using different styles, but it hits problems over 135. Whatever the velocity, my angles and arcs want a grooove, a reliable motor they can lock onto. My default choreography likes those circular rhythms that have the next cycle moving out while the current one is still working its way round. Above all, I crave repetition. Music that freezes time by looping it forever. Holding those calligraphic shapes in suspension so you can really bite down on the electricity they spark in your brain.

The right sequence of thumps, pats, clicks and crashes can make you weightless. A great rhythm lifts you off the ground so your energy is spent dancing back to Earth rather than pushing against it. To do their best work, my joints need beats with bounce; anything too inelastic becomes an effort. Last weekend I stayed up all night in a forest with Glasgow’s Optimo. They kept me on my toes despite the mud, long after bedtime, even with their high-energy and hardcore interludes, because whatever they played always had plenty of bounce.

I’m all about the one. The funk. Or a solid four-on-the-floor. I can move to drum and bass if I have to, but its skippiness chokes me with reverb. All those beats start to bottleneck and defuse each other. To try and meet the music, I gear down into the groove and dance on the half-speed like reggae. But that feels as if I’m not respecting the track – not paying back enough energy. So every few minutes I go wild to the full tempo. But that’s no good either because I still can’t relax into an unbroken rotation. Also, it sounds too much like 1994.

For a dancer, music is furniture. Architecture. It’s the world you move around. The kickdrums thump out a path, cymbals slash the air, silver strings stretch tight above your head. The best definition of music is “organised noise”. When you’re dancing, the producers and musicians design environments for you, then the DJ leads you through them.

Suzuki’s record, Yuri Suzuki, was released by Chicago house label Trax Records in 2020 (image: courtesy of Yuri Suzuki).

Sound artist Yuri Suzuki builds musical scenery. His raw materials are sound and innovation, combined in curious instruments that invite participation and generate smiles. “I want to create a playground,” he says. This puts him at the sharp end of design: making seductive objects to interact with humans. Modules clip together like a construction toy to clarify the mysteries of electronic circuits. A toy train turns your scribbles on paper into its sound track. Beautiful sculptures translate digital signals back into analogue instruments. A microphone lets you bash a drumkit with your voice.

With roots in product design, Suzuki began his career making fun musical electronics for Japanese pranksters Maywa Denki and playful synths for Teenage Engineering. He is intrigued by the effect of sound on humans in all its forms, toying with audio in public art pieces staged from Milan to Singapore, Tokyo to San Francisco. He has lectured at the Royal College of Art, was previously a partner at design consultancy Pentagram and a member of the BBC’s New Radiophonic Workshop, and he’s also both a producer and a DJ in the conventional sense, with many releases, including on foundational Chicago house label Trax.

His latest work is an invitation back to 1988, when the dual technologies of ecstasy and house music came together in thousands of dancing bodies. The resulting “acid house” culture brought a fractured nation together in the face of Thatcher’s militant de-industrialisation for a wave of illegality: raves, warehouse parties, sound system convoys. It transformed social attitudes, broke down class and race barriers, and defused UK pop culture’s violent tribalism.

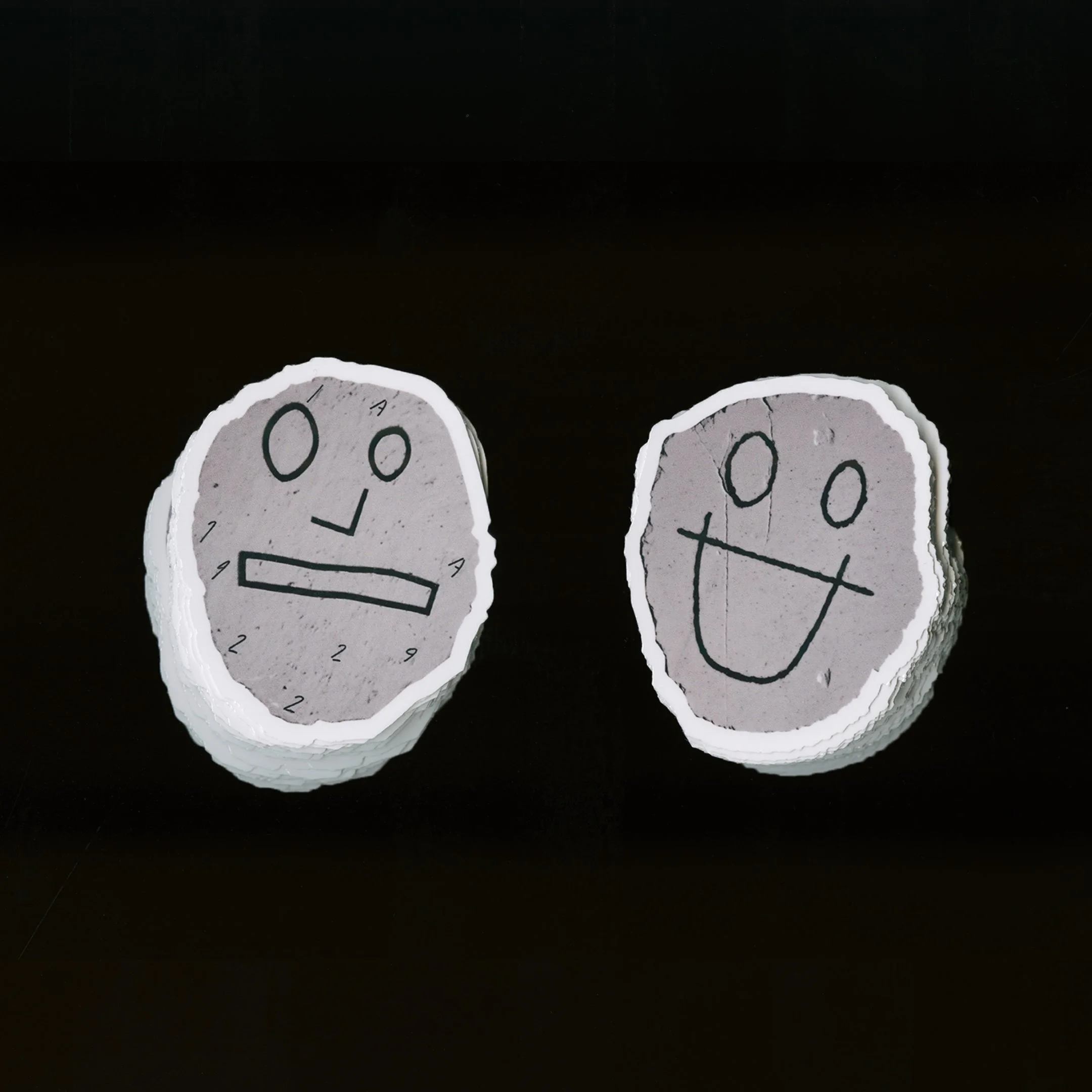

AI Acid’s artwork by Jody Hudson-Powell and team at Pentagram (image: courtesy of Yuri Suzuki).

“Techno and acid house brought up so much cultural possibility,” Suzuki says. “My work is a perspective on design and art, but I always feel attracted to Detroit and Chicago and techno culture. That’s my main inspiration at the moment.” For a Japanese kid born in 1980, the period is fascinating. “The second summer of love in the UK in 1988 created a movement,” he says. “It’s not only one music scene, the whole country was into that acid house party. It was a protest as well, against the Conservative government. The producers were activist, like KLF, Psychic TV and Underground Resistance.”

The revolution was British, the music originally American, but at the heart of it was Japanese product design. Dance music in the 70s needed expensive studios, professional producers and engineers, session musicians, often whole orchestras. But in the mid-1980s, house and techno was the sound of amateurs and consumer electronics: Akai samplers, Roland drum machines, Casio keyboards. Clubbers and DJs grabbed the means of production and put the machines centre stage.

Acid house was a specific genre style before it was a movement. While most early Chicago house records seemed content to reheat disco, “acid” house was aggressively futuristic: alien tracks built from warbling digital squirts. This style, first encoded in Phuture’s 1987 release ‘Acid Tracks’, was as much discovered as created: the signature acid squelch came from the presets of a Roland TB-303 Bass Line machine, pushed to distortion levels by a trio of Chicago DJs. As DJ Pierre told me in 1997: “I started turning the knobs up and tweaking it and they were like, ‘Yeah, I like it, keep doing what you’re doing.’ We just did that, made a beat to it, and the rest is history.” Here was music derived purely from the soul of the machine.

“There’s another way to think of AI art. It’s not that this music, or this image, sprang from nowhere; rather it’s a co-creation, a collaboration with thousands of previous minds. ”

Suzuki’s AI ACID: Digital Echoes of Second Summer is an album of tracks evoking the classic acid sound. As a text-originated AI project, it is built from nothing more than words and memories – words input by the artist evoke machine memories of the world’s music. “I was thinking, what if AI can create acid house, acid techno, even if there’s no human hand in there apart from writing text?” he tells me.

The best AI art can feel like it was found, not made, and Suzuki’s work revels in this ambiguity. At first the AI model he used – Google’s MusicLM – was largely ignorant of the style descriptions he was entering. The public AI music sites have been slow to develop much sophistication because copyright limits the data they can be trained on, and most platforms won’t let you reference actual artists or tracks in your prompts. But Suzuki persevered, and the AI eventually got on one matey.

The tracks are each just 1m20s long, suggesting fragments. They zip through different acid styles, and could conceivably be discoveries as much as creations, the spoils of a dusty vinyl basement. Suzuki’s description invokes “the crossroads of tradition and innovation… an unforeseen fusion of coincidence”. Are we listening to history or memory? Pastiche, homage or re-creation? The artist’s prompts instructed a machine mind to generate unique new music in a style based on its accumulated knowledge of a historical genre created from the presets of a failed 1981 music machine (which itself was designed by a human mind, Tadao Kikumoto). There are a lot of layers.

Suzuki’s 2019 sculpture The Welcome Chorus played AI-generated Kentish folk songs out of colourful horns (image: courtesy of Yuri Suzuki).

At around 150bpm these tracks are well beyond my velocity, and the beats are thunderously inflexible. I close my eyes to enjoy them, starting to imagine a dark basement pulsing with strobes. There would be smoke and physicality, people crammed in dancing fit to bust. I recall moments when the energy drove me to that place: a Richie Hawtin rave in Toronto, a club called NASA in 90s New York. I summon others that I missed: Detroit’s Music Institute, Chicago’s Music Box. Or the raves around Slough and Hazlemere, immortalised by Gavin Watson in Raving ’89, a book I published. “More punk than punk ever was,” was his brother Neville’s verdict, who makes great acidinflected music to this day. Then I think of visual projects by AI artist Omar Karim, who “discovers” images of the scenes I’m imagining, undeveloped film found on the floor of raves that never happened.

There’s another way to think of AI art. It’s not that this music, or this image, sprang from nowhere; rather it’s a co-creation, a collaboration with thousands of previous minds. AI’s ability to juggle vast datasets brings the power of composite creativity. Some artists develop fictional creatives with rich backstories – a 1950s Martian photographer, an edgy Victorian stylist. Another approach is to crowdsource art from multiple living minds.

In his 2019 sculpture The Welcome Chorus at the Turner Contemporary gallery in Margate, Suzuki generated Kentish folk songs from the transcribed words of 3,000 people. Workshops across the county gathered their thoughts, and an AI trained on local folk melodies turned them into songs. Gallery visitors were met by 12 singing horns at people height. “Each horn has one specific voice,” he explained, “so you feel like you are standing in front of a choir.” Despite their synthetic voices, the songs were warm and authentic, and the sculpture conjured a choir’s communal spirit. AI made this egalitarianism a reality. “It’s an impossible task for one human being to consolidate 3,000 people’s different opinions to make one song,” says Suzuki. “The only way to do it was use an algorithm to learn about old lyrics and melodies, based on the people’s contributions, then create brand new songs.” Instead of an artist selecting a few privileged elements, he made a composite mind – a genuine 3,000-way collab.

Another AI piece reclaimed the memory of a forgotten music machine. Suzuki tells of Raymond Scott, a 50s engineer and bandleader who built the first sequencer, the Electronium. An early milestone of generative music, this played a unique counterpoint to any melody the user entered. Scott used it successfully for years, composing music for the Looney Tunes cartoons, and also became the “chief researcher for advanced music” at Motown, where label boss Berry Gordy believed the Electronium would automate his pop conveyor belt. “It’s the first instrument that writes music on its own,” boasted Scott. “And it never writes the same song twice.”

With the machine long decayed, its current owner, Mark Mothersbaugh of avant-popsters Devo, had given up hope of its resurrection. But Suzuki and his AI collaborators were able to make it sing again. “I knew AI was capable of doing this, because what Raymond Scott wanted to do was AI music. He wanted to make generative music.” Suzuki created an AI-derived model of the machine from its circuit diagrams and, using Google’s Magenta platform, coaxed music from it, releasing an album of the results in 2020 that he named Scott’s Dream.

As a DJ, Suzuki is practised in musical seduction. “Engagement of the audience is the main thing I seek,” he says. “I always look at people, how they behave, how they react to the music. I want the next track to make a natural transition, I like to make a narrative connection also – a link to a sample or a producer or lyrics, but most important is to predict how the record will make the audience feel.” He keeps a careful eye on the dancefloor’s energy, too. “It has waves. People get tired, so you need to make an oscillation through the night.”

The cassette of Scott’s Dream, an album Suzuki made using a vintage Electronium, the first sequencer built by engineer and bandleader Raymond Scott in the 1950s (image: Pentagram).

Good DJ-dancer communication is two-way, and the same logic applies to his sculptures. “I’m working a lot with public art installations and the process is very similar – how the audience or the visitors interact with the installation is very similar to the DJ process.”

Much of Suzuki’s work reflects the science behind music’s power to engage.“I’m interested in ambient projects because it brings comfort to people,” he says. “Human brains find it easy to hear patterns, but with ambient music you can avoid duplication. It needs to be something unrecognisable, a loop. White noise is particularly good, because we remember being inside our mother’s body, so white noise is very calming.”

Alongside his art, Suzuki has a commercial practice developing sonic branding, something I’ve done too. We share the frustration of seeing so few clients appreciate the power of audio. Most brands have hundreds of pages of visual guidelines but often don’t think at all about what their world might sound like, despite the fact that hearing is a more emotional sense than sight, and aural recognition is far faster. “We think with our eyes and we feel with our ears,” as Malcolm Gladwell puts it.

Suzuki’s graphic design for Scott’s Dream (image: courtesy of Yuri Suzuki).

There are other certainties. Humans have mirroring circuits, so we get more pleasure from music if we can see others enjoying it too. And recent research reveals that we possess “aesthetic resonance”: when our brains are lost in music, they don’t just receive it passively, neurons fire in response and create sympathetic waves. In a measurable way, your brain is vibing along, a bit like dancing. Thanks to this, an AI can tell from a brain scan which song we’re listening to.

An associated phenomenon emerges when you play with the separation of the sound signal. “I did some pieces using binaural sound,” says Suzuki. “There’s a lot of research on it. Basically, if the left and right ears have a slightly different beat tempo in the low frequency, it makes concentration better – it’s easier to focus on work.”

Music is often used for performance training. “People are saying sound is a drug in a way, a way to increase your body’s performance,” Suzuki says. “I think sound definitely has that capability to increase your hormones.” High-tempo pulse-raising workout tunes are the obvious example, but the opposite effect is possible, too. Olympic archers practise against a heavy metal soundtrack so they can train for extreme relaxing under pressure.

“I’m quite excited about creating a brand new music genre. That’s my dream.”

Music works by balancing familiarity with surprise. Perhaps we have this tension because our hearing evolved with a dual function: sound comforts us with a heartbeat or a lullaby, but the same sense alerts us to wild beasts and dangers overhead. Great music makes the balance precarious. Trusted rhythms and reassuring chord progressions pitted against unpredictable rimshots, a guitar ambush, a scribbly mess of synth. Regularity v improvisation, order v chaos, expectation v shock. My noodle quotient is low: I can’t engage with music that revels in its irregularity without also propelling itself with something solid. All jazz, no booty and I’m out. Acid music is powerful because its structures can be really simple, even when its bubbly machine textures are bewildering.

Electronic music machines exploded the non-musician’s possibilities, letting DJs and club scenes evolve entirely new styles, including acid house and many before and after. Today, the machines are powerful enough to shortcut the process and take on the whole creative brief. Yuri Suzuki’s ambition is to stir the circuits at the highest level. “I’m quite excited about creating a brand new music genre,” he says. “That’s my dream.”

Words Frank Broughton