Four Legs Good

The S 243 stacking chair, designed by Frank Rettenbacher for Thonet (image: Alan Archutowski).

In the early-20th century, the Thonet furniture company emerged as a key protagonist in the modern movement’s development of new typologies of tubular steel furniture. The company had already achieved renown in the 19th century for its bentwood seating, not least the celebrated 14 café chair, yet throughout the 1920s and 30s Thonet came to specialise in the development of metal chairs whose curved shapes would recall aspects of the brand’s earlier work in wood, albeit recast in a material more befitting of the machine age.

Today, a series of chairs from that era of Thonet’s design work still remain in production. Marcel Breuer’s S 32 (1929/30) suspends a wicker work seat over its swooped steel framework; Mart Stam’s S 33 (1926) and S 43 (1931) similarly soar over loops of metal, casting their seats in leather and moulded plywood; while Mies Van der Rohe’s S 533 (1927) is the most formally dramatic of all, balancing the user atop rolling curves of steel. There are many differences between these projects, all of which served as important markers in Thonet’s wider tubular steel programme, but one similarity is obvious. They’re all cantilevers.

The design is intended as a continuation of Thonet’s tubular steel chair programme, begun in the 1920s (image: Alan Archutowski).

“Back in the 1920s and 30s, everything in that category of tubular steel chairs was a cantilever,” notes Frank Rettenbacher, an Austrian contemporary designer whose studio is based in Amsterdam, where he serves as creative director of the A.D.O. Amsterdam Design Office. While Rettenbacher’s work at A.D.O. is centred on the world of consumer electronics, with A.D.O. serving as the in-house design agency for Philips TV and Audio, he has also operated an independent design practice since 2013 within the realm of furniture, with the bulk of his collaborations coming through Italian brand Zanotta: his Mina table is built around steel wires that hook around one another to form an understructure, while his Ivo stool also employs steel rods to strengthen its solid wood form. Yet a meeting with Thonet at the IMM Cologne trade fair in the early 2020s led to a new challenge, with Norbert Ruf, the company’s creative director, inviting Rettenbacher to address what he saw as an omission in the brand’s collection. “When I started talking to Thonet, the brief was fantastic,” Rettenbacher explains, “because they felt that they didn’t have a four-legged tubular steel chair in their portfolio.” The task before him, he explains, was to remedy this. “I was basically asked to fill that gap,” he says, “which was an amazing honour.”

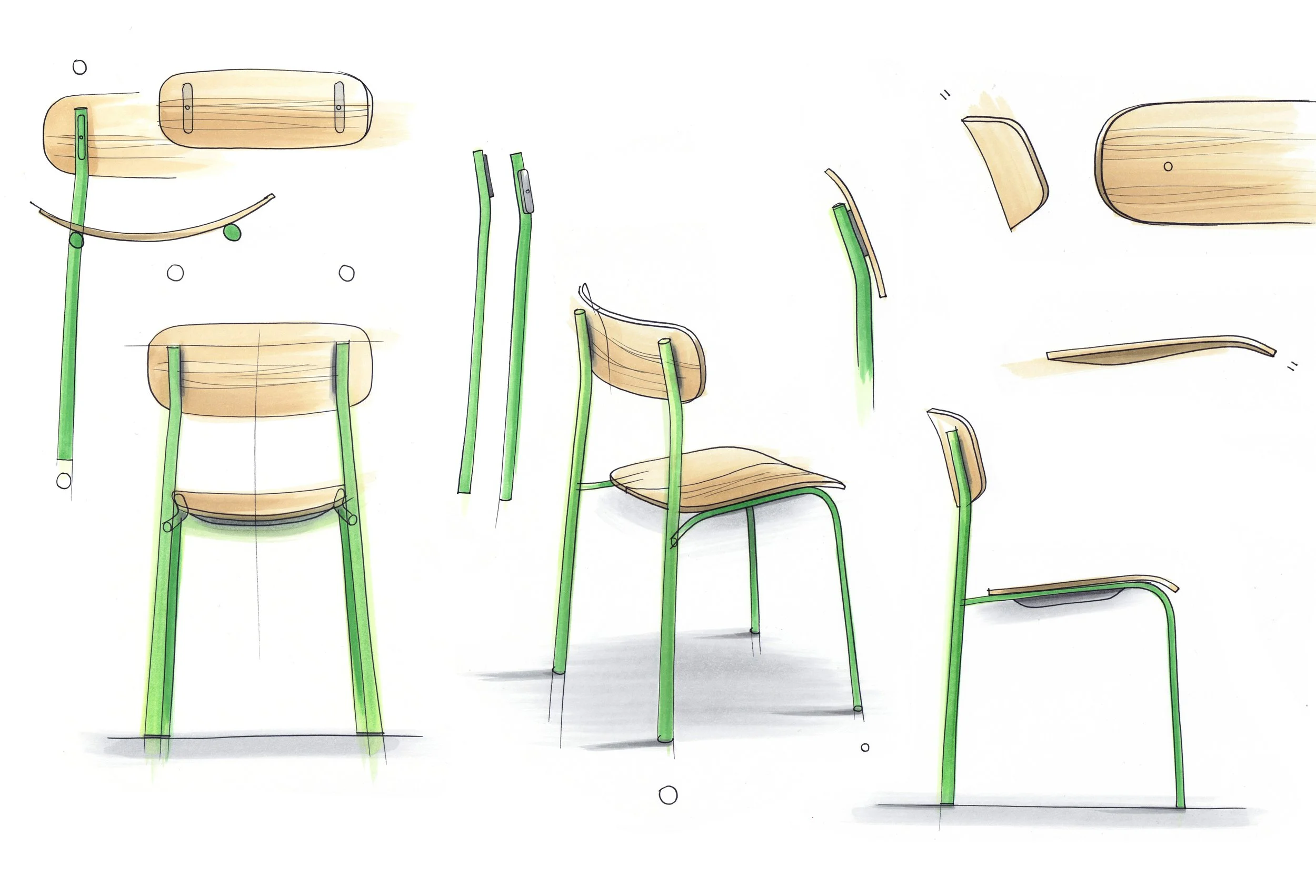

Rettenbacher’s development sketches of the chair (image: Frank Rettenbacher).

While Thonet does offer a selection of four-legged steel chairs within its catalogue, such as Industrial Facility’s S 220, all of these designs feature a single seat shell, whereas Rettenbacher’s ambition was to create a more open structure with a separate seat and backrest – a design that would place its metal framework front and centre, and thereby continue in the same vein as the brand’s 20th-century offerings. The project began, Rettenbacher explains, with a desire to recall the design language of Stam’s S 43, which was notable for its pared back structure and reduction of extraneous detail, but with the ambition to recast this approach in a new, more versatile form that might round out the brand’s portfolio. “That was the challenge of the whole project,” he says, “because you want to reflect [the S 43], but also find your own modern expression, or develop a contemporary design that stands on its own.” The goal, he explains was to interpret this challenge in the form of a stackable four-legged chair that would prove adaptable enough to work across domestic space, while also proving suitable for the rigours of hospitality and office spaces. “But there are so many chairs out there in this segment of the market,” Rettenbacher observes, “so what do you do?”

Prototypes of the chair, photographed in Rettenbacher’s studio (image: Frank Rettenbacher).

Rettenbacher’s answer to these questions is the S 243 – a design that is intended to be contemporary, but which also references aspects of its predecessors in Thonet’s range. The chair’s steel back legs angle up and inwards, before bending back to accommodate a plywood backrest, while the front legs tuck down from its scooped seat. To develop the design, Rettenbacher explains, “I started to scan Thonet’s portfolio, and I realised that all of these cantilever chairs have a diameter of 25mm for the tubular steel – I thought that was a good starting point.” A 25mm tube, however, is thick and robust, with Rettenbacher reasoning (in much the same fashion as designer Jean Prouvé did in his famous 1934 Standard chair) that this kind of strength was only actually required in a back leg, where the majority of the force of sitting is directed. “So I realised we could make the front legs thinner, which gives it a bit more elegance,” he says. This design detail played a functional role in that it aided with the chair’s stackability, with the S 243 featuring small stacking pads towards its back legs to prevent scratching when they are placed atop one another, introducing a sense of clarity and precision in the design’s construction, which in turn help to generate the chair’s character. “It’s a touch of personality,” Rettenbacher explains.

Frank Rettenbacher and the S 243 (image: Fabien Frinzel).

To ensure the chair’s competitiveness on the market, Rettenbacher designed the S 243 to require as little specialised tooling as possible in a bid to keep production costs down, and therefore lower the cost for the final consumer. As a designer accustomed to working in the realm of consumer electronics, “where it’s all about millimetres, whereas chairs and furniture are normally centimetres,” he quips, this meant that he would instead focus his design on small details, rather than bold expressive forms. Whereas the S 43’s backrest connected to its frames through four screws, for example, Rettenbacher’s design strips this back to a single connection point on each side, with a spacer introduced between the two materials to achieve a lighter visual effect that allows the plywood to float at a distance from the metal. In chairs such as Breuer’s S 32, meanwhile, these connecting screws are visible on the back of the chair, whereas in Rettenbacher’s design they are concealed to leave no obvious connection point when seen from the reverse. “It gives you a cleaner back, because most of the time the chair is tucked under a table,” he says. “In general, I think that’s the type of designer I am. I'm very rigorous and perfectionistic in many ways. I don’t think a lot of companies give you the room to play and to go into those details.” A positive corollary of this approach, which prizes legibility and clarity of construction, is that all of the chair’s components can be easily replaced or repaired, thereby extending the chair’s lifespan. “Modularity is key,” Rettenbacher stresses.

A leg detail of the chair, showing the stacking pad (image: Fabien Frinzel).

Across the chair, small construction details – the connecting screws; the feet produced at an angle to keep flush to the floor rather than protruding from the steel; the spacers; and stacking pads – are all executed in black as a highlight colour, whereas the rest of the chair has been produced in a range of tones. Alongside more familiar shades of silver chrome and natural wood, Rettenbacher has also created editions in rust red and olive green, produced in a high gloss powder coating. “Traditionally, Thonet has been very much into chrome, but in the past decade you’ve seen a lot of Scandinavian brands go towards more muted, static colours,” Rettenbacher explains. “So I wanted to do some colours too.” While the range of tones that he selected for the design “needed to have a certain sophistication,” he was also adamant that “it should still have a charm.” As such, colour became a means by which Rettenbacher could express the contemporary approach of the chair, but also link back to the company’s past. In determining the palette, for instance, Rettenbacher looked back through Thonet’s archives, coming across a series of chairs designed by 20th-century Austrian architect Josef Hoffmann. “He’s always been a great inspiration,” Rettenbacher says, “and I saw a few chairs he’d done for Thonet in this beautiful red. I’d always liked the idea of doing a completely red chair, so that became the starting point.”

The chair’s red colour is an homage to earlier work for Thonet by Josef Hoffmann (image: Alan Archutowski).

In this respect, the S 243’s colour palette serves as an embodiment of Rettenbacher’s project as a whole – an attempt to create a chair grounded in Thonet’s past, while also gesturing towards the company’s future. It is, he says, a balancing act that is captured in the design’s name. It is no coincidence, for instance, that the S 243’s name recalls that of Stam’s S 43. “Every Thonet design has a number,” Rettenbacher recalls, “and the 43 in the S 243 is a nod to its historic predecessor.” It’s a linguistic hint towards the ancestry and purpose of Rettenbacher’s chair, albeit one that the final design wears lightly. “I think very few people will notice,” he says, “but it’s a nice detail if you know there’s a little link in there.”