Socially Kinetic Colour

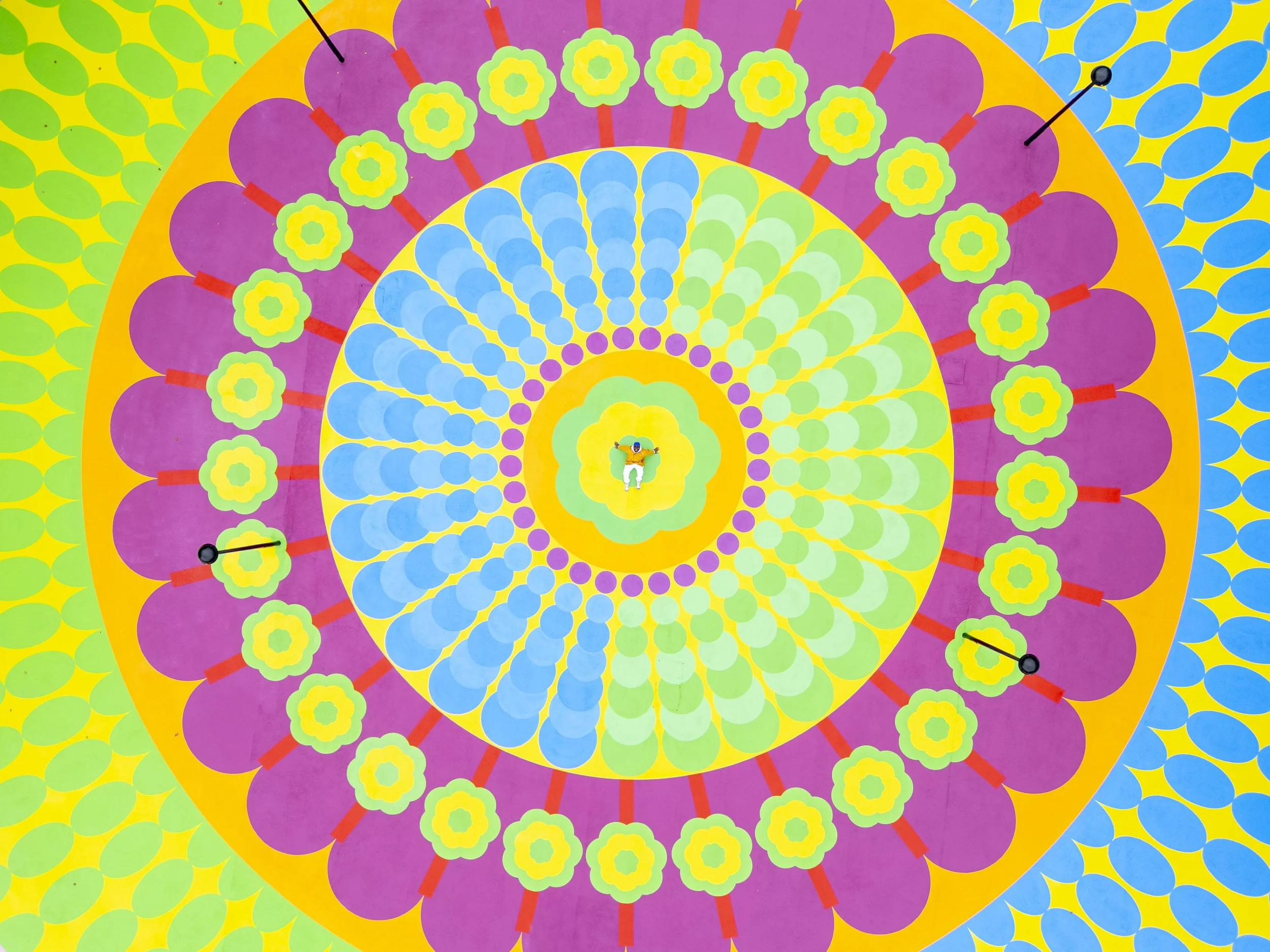

Yinka Ilori, photographed in his Walk With Your Dreams mural in Milton Keynes (photograph: Stephen Chung).

“I really care about creating work in public spaces for people who don’t get access to art.” So spoke Yinka Ilori in Disegno #33, in dialogue with writer Georgina Johnson about his growing interest in public murals. The design work he hoped to create, Ilori told Johnson, would be for those “who can’t afford to get the bus or train to a museum, or who don’t feel comfortable going to those places.”

This reference to trains, albeit in a different form to that originally intended, has now proven prophetic: last week saw Ilori open Walk With Your Dreams outside of Milton Keynes’s train station, his largest public mural to date. Spread across the full expanse of the city’s Station Square, rich in the two-dimensional interplay of colour and pattern that is distinctive of Ilori’s work, the mural is the first thing that those arriving in the city by train will see upon exiting the station. “That [site] is what first drew me to it,” Ilori explains. “With my work, especially when you come to my studio, you cannot control your emotion. I think with this artwork, when you come out of the station, you're going to want to run into it, you’re going to want to smile. I think kids will love it, and I’m hoping it becomes a place where people can sit down, reflect and engage.”

An aerial shot of Walk With Your Dreams, showing its expanse across Station Square (photograph: Stephen Chung).

Commissioned by Milton Keynes City Council, Walk With Your Dreams replaces the previous iteration of public space in Station Square – a 28,000sqm field of grey concrete lined by modern office blocks that had, perhaps understandably, fed into negative stereotypes surrounding the city. “Something you hear from people who haven't been to Milton Keynes is that we can come off a bit soulless,” notes Shanika Mahendran, Milton Keynes’ Cabinet Member for Planning and Placemaking, “[whereas] I think [Walk With Your Dreams] really embodies the soul of our city.” Mahendran’s mention of seeking to transform attitudes surrounding the city is apt. Milton Keynes was founded in 1967 as one of the new towns developed by postwar British governments, and, despite many of the considerable boons gleaned from its progressive planning – today, the city is 35 per cent green space, with a plural population of whom 34 per cent identify as hailing from ethnically diverse backgrounds – it has also attracted criticisms common to modernist developments, frequently focused on the rigidity of its grid and a perceived artificiality.

Ilori and Walk With Your Dreams (photograph: Stephen Chung).

Faced with these issues, Ilori’s mural is intended to introduce a more fluid, vibrant entry point to the city’s grid, which Mahendran describes as “highlighting the vibrancy and the diversity and creativity in the city.” To capture this, Ilori’s artwork swirls in circles of lime, yellow, blue and pink, bordered with Prairie-grassland planting overseen by landscape architects Planit, who have also seeded the square with mature plane trees to introduce verticality to its broad horizontal vista. Radiating out from the circular centre of his mural, Ilori has painted tractor beams of candy pink stripes that draw visitors down into the twin underpasses that lead out onto the similarly plane-lined Midsummer Boulevard, Milton Keynes’ central artery. “There are different paces within the artwork,” Ilori says, “I want you to run down those [stripes], whereas when you’re in the middle of everything, that’s slower and circular. It’s a moment to reflect.”

Ilori’s design approach towards public art has often worked around the interplay between pattern and text, with works such as Better Days are Coming I Promise, Love Always Wins and This Is Human Kind pairing their colour work with affirmations and direct calls for social cohesion. By contrast, Walk With Your Dreams avoids this approach in favour of greater abstraction, relying upon immersion within the artwork itself as the means through which its social messaging might be achieved. “I think I was more and more interested in actually letting the audience form their own perception of what this makes them feel,” Ilori says. “I think living in Milton Keynes, there is a kind of dream-like experience and excitement around the fact that it’s only 50-years-old.” The artwork, he explains, hopes to evoke something of the optimism surrounding the city’s founding, and reflect the diversity of its community, as well as the abundance and generosity of its green spaces. “We’re at a very difficult time now around the world, with so much pain and so much war, [whereas] this is about celebrating people,” Ilori adds. “I think we forget the strength that comes when we come together, rather than remaining in a place of division and pain and confusion.”

The planting for Walk With Your Dreams was designed by Planit (photograph: Stephen Chung).

Walk With Your Dreams seems a fitting culmination of Ilori’s career to date, not purely in terms of its scale. Since his early bricolage work with upcycled chairs, using hacked seating forms to convey the Nigerian parables he was told as a child, Ilori has been consistent in his design approach. Whether working across personal projects, public art installations, or product design, Ilori’s interest lies in the capacity of colour combinations to narrate often underreported stories (a central theme to his work is the translation of the personal elements of his British-Nigerian upbringing – be it garments, interiors or narratives – into public space), and trigger an emotive response in audiences. Ilori’s work with colour and pattern may be technically sophisticated and subtle – and rich in its references to Nigerian wax cloth fabrics and the different treatments and social significances of colour across communities – but the effects he is interested in are always broad, direct and universal. Ilori resists the over-intellectualisation of his work, and often speaks in terms of immediately understandable concepts such as joy, as well as emphasising his design’s social impact. “I think it’s about trying to reassure people that their ideas are heard and listened to,” Ilori told Johnson of his approach towards collaboration in Disegno #33, but the same might be said of his design work itself. Ilori emphasises inclusion and openness above all else.

Photograph: Stephen Chung.

In Walk With Your Dreams, the social themes of Ilori’s work have been allowed to come to the fore in a manner that is not possible in all areas of his practice. As the renown of Ilori’s studio has grown, an increasing number of brands have sought out partnerships across editions and one-off products that range from watches and cars to packaging and bags. There are, perhaps, few arenas within design in which ideas of joy and celebration are not welcome, but Ilori’s aesthetic takes on greater emotive resonance in social contexts such as Walk With Your Dreams, or his earlier Flamboyance of Flamingo playground, in which pattern is not only pattern, but also an enabler of the life that surrounds it. The Milton Keynes mural is vibrant, swirling and aesthetically kinetic, but is ultimately static colour, painted on on the ground. What brings Ilori’s work to life and motion, however, are the quivering feather grasses that Planit have bedded around it, which have been seasonally landscaped to complement tone in the artwork and draw pollinators to the area across the year; the people drawn across its multicoloured circles as they pass into the square from the station, and onwards down the pink stripes and into the city; and the communities who can gather on its surface, shaded by plane trees.

Photograph: Stephen Chung.

“I’ve been doing murals for ten years now, and colour has always been my strongest point,” Ilori says. “I think sometimes we forget the importance of colour within a space and how it can change space. It can make a space bigger, smaller; it can invite people in. I think I always try to work out what experience I want you to have in that space with the colours. So if I'm looking at pinks or yellow, am I trying to uplift your mood? Am I trying to tap into a certain type of emotion? Am I trying to bring you together?” Colour is a catalyst in Ilori’s work, deployed in service of drawing in the people, and triggering the emotions, that might complete his intentions with the spaces and objects he seeks to create. “Certain colours can make people sort of feel some way: they want to engage, they want to talk,” he says. “That's powerful, because just by [using] colour, we can engage. And I love that.”

Words Oli Stratford