Preteen Dreams

The Tamagotchi Connection, which was first released in 2004, has been rereleased 20 years later for the children of the millennials who grew up with it to enjoy (image: Bandai-Namco).

You know the feeling: when you pat your pockets and realise it’s not there. You throw open your bag and rummage through in a haphazard way that speaks to your rising level of panic – but it’s not there either. Your stomach lurches, its absence crashing down upon you.

That’s how I feel when I lose my phone, too, but at the moment I’m searching for my Tamagotchi.

For readers who weren’t pulled into a nostalgic reverie by the mere mention of its name, the Tamagotchi is an egg-shaped digital pet that was one of the biggest toy fads of the late 90s and early 2000s. The device features three small buttons, and soon after turning it on, an egg made from a handful of pixels appears on its tiny black and grey screen, which quickly hatches into an alien character that the user must attempt to raise into adulthood. According to The New York Times, the toy sold out so quickly in the first six months of its release that Japanese shoppers began camping outside stores to secure one, and within three years developer Bandai had sold more than 40m units worldwide.

“Pets are only cute 20 to 30 per cent of the time, and the rest is a lot of trouble, a lot of work,” Tamagotchi inventor Yokoi Akihiro told The New York Times in a 1997 interview explaining why he created a toy that regularly demands its users feed it, play with it, give it medicine and clean up its poo by emitting high-pitched beeps. “But I think that you also start to love them when you take care of them.” Yokoi understood that the flip-side of love is loss: left unattended for even half a day, the Tamagotchi would die from neglect. To avoid this macabre fate, children began taking it with them everywhere; The New York Times even reported that some children dropped their pencils during a timed standardised test in order to check on their toys. The Tamagotchi’s grip upon users was new and startling: researchers coined the term “the Tamagotchi effect” to describe the phenomenon of humans starting to develop emotional attachments to machines.

Pixel graphics of the Original Tamagotchi’s characters (image: Bandai-Namco).

Many critics consider Tamagotchis to be a precursor to our contemporary relationships with smartphones. Academic Laura Lawton even argues that the Tamagotchi influenced the developing mobile technology market and “prepared people for the constant presence of technology that we are so familiar with today”. The Nokia Communicator, a mobile phone that opened like a clamshell and had SMS capabilities as well as (painfully slow) internet access, was released in 1996, the same year as the Tamagotchi. Only a few months later, a downloadable Tamagotchi ringtone was available for purchase, and Lawton notes that advertisements increasingly began to anthropomorphise mobile phones, giving them arms, legs and faces. Bandai even released the Tamapitchi device in Japan the following year, which combined a standard phone’s functions with raising a Tamagotchi, and then released the Tamagotchi Connection worldwide in 2004, which used infrared technology to allow users to connect with nearby devices.

Tamagotchis were soon eclipsed by Furbies: fuzzy robots programmed to speak their own language, which became the next toy fad. While Bandai (which merged with video game and entertainment company Namco in the mid-2000s to become Bandai-Namco) frequently continued to release new models of the Tamagotchi in Japan – including a Christmas-themed iteration where users look after Santa Claus, and a model where they can parent the devil – the company released far fewer abroad. But this all changed in 2019, when Bandai-Namco re-released the original Tamagotchi globally and launched the Tamagotchi On, the first international version with a colour screen. Over the last five years, it has continued to launch new generation models with ever more complex features, such as a camera and motion sensors, while also kicking up nostalgia by re-releasing the Connection this year, on its 20th anniversary.

The model that Bandai-Namco has loaned me for this essay is a re-release of its first ever digital pet. When I finally find the device at the bottom of my backpack, it greets me by bouncing up and down. I’ve turned the sound off, so it opens and closes its mouth inaudibly, like a cat meowing from behind a window. When I spy a steaming pile of poo, I surprise myself by stroking the device with my thumb and making a cooing sound before I clear it up. Although I would never act so tenderly with my iPhone as I do my Tamagotchi, my phone has been in my hand all night – I wouldn’t even think to let it go.

Image: Bandai-Namco.

The Tamagotchi has been welcomed back into the zeitgeist in recent years, for which there’s a couple of obvious reasons: many people rediscovered and took comfort in old hobbies during pandemic lockdowns, and Y2K style is back in fashion, making its aesthetics bang on trend. Nowadays, Tamagotchis are even sold at Urban Outfitters, as well as in more traditional toy retailers. “I think nostalgia is just generally really popular at the moment,” Tamagotchi brand manager Priya Jadeja tells me, adding that sales skyrocketed even before the pandemic. “It’s also a play pattern that is quite unique and original.” The resurgence makes sense: many of the millennials who were part of the first wave of Tamagotchi fans now have kids of their own who they are keen to share the toy with.

After anxiously checking on my Tamagotchi at a work event, filled with concern that it had passed away during an hour-long panel talk, I strike up a conversation with someone who happens to relate. Alice Dousova owned a Tamagotchi as a child and recently bought one for her six-year-old daughter, Mélodie. “I always thought it was an incredibly sophisticated toy,” she laughs, comparing it to other games she played at the time, such as Tetris. “Now I see how incredibly simple the graphics are, but it’s still really fun.” Both Alice and her partner enlisted their parents to help care for their Tamagotchis back in the day, and now provide community care for Mélodie’s, with Alice hooking the Tamagotchi’s keychain through the belt loops of her jeans. “I quite enjoy it, it’s a conversation starter when it beeps at work,” she says.

I don’t have a child and I wasn’t allowed to own a Tamagotchi when I was younger, but luckily I now get to live out my preteen dreams. My Tamagotchi is very cute: its shell is pink and white with berries on it, and I show it off excitedly to many people in my life, most of whom don’t care. But once the novelty wears off, it feels much more like a chore than a toy. My resentment increases as my character grows up: midway through day three, it evolves into Kuchipatchi, a large blob with duck-like lips that it continuously smacks together in a way that feels ungrateful. Two days later, it grows legs and pops its hips from side to side in a mocking dance routine. When I ask Alice if she shares my feelings of resentment, she responds graciously: “As a mum, you have so many extra chores that it doesn’t really feel like a big deal.”

An illustration of the first-generation Tamagotchi character Kuchipachi (image: Bandai-Namco).

When the Tamagotchi was first released, it was primarily marketed to girls, and in her book Millennial Monsters: Japanese Toys and the Global Imagination, cultural anthropologist Anne Allison writes that the Japanese edition of the device’s guidebook was even designed to look like the health records women used to chart the growth of their babies. A year later, Bandai released Digimon, Tamagotchi’s masculine counterpart, which allowed characters to fight as well as play. While children of all genders clamoured for a Tamagotchi, defying its gendered marketing, back in the 1990s the responsibility of helping children to care for their devices still largely fell on mothers. “One of my friend’s mums ran a Tamagotchi daycare,” Jadeja remembers. Though I’m sure that many mothers still do the lion’s share of Tamagotchi care, I am pleased to hear that Alice’s partner, having grown up caring for one himself, is also invested in Mélodie’s digital pet.

I can track my own caregiving skills via three on-screen meters that show whether my Tamagotchi has received enough food, play time and discipline. Nevertheless, I can’t bring myself to press the discipline icon, which resembles Pac-Man shouting, particularly often. I’ll admit that sometimes its refusal to eat the sweets I offer inspires a spontaneous fury within me and I enjoy pressing it maliciously, but most of the time this feature just confuses me. Whenever I do use discipline, my Tamagotchi fumes back at me, emanating small black clouds of frustration that make it look like it’s farting in revenge. It never backs down, so I just feel like I’m stoking greater animosity between us. “I want it to die but I don’t want to kill it,” I whine to my partner at the end of week one, as I clean away poo while nursing a hangover.

“You’re going to be such a good mum one day,” he laughs.

The Tamagotchi Uni, released in 2023, has a colour screen and encourages a softer parenting style (image: Bandai-Namco).

The Tamagotchi is parenting me as much as I am parenting it, and this becomes extremely apparent once I try out a different model.

The latest of the new generation models, the Tamagotchi Uni (2023), is wifi-enabled so that its games can regularly refresh, and has a colour screen and a pink wristband so you can wear it like a smartwatch. In comparison to the Original, the Uni feels like a cosy paradise: my character has its own home, and I can take it for walks in the park or swing by the arcade. Its kitchen has mint green checkerboard floors and the bedroom has a circular window that frames the changing sky. I can rack up points by playing games or completing care tasks, which I can then use to personalise my space by visiting the Tama mall. It only sells essentials, such as bagpipes, a framed portrait of a pumpkin, and a Marie Antoinette-style sofa.

The Tamagotchi brand does an impressive job of bridging nostalgic play with new technologies. “It still keeps some play values alive that are found in other things, like when kids have dolls that they nurture,” Jadeja says. But the caretaking features in the Uni are much more complex: even if two users get the same character, its traits will be influenced by the care they give it, creating the impression of more developed personalities. My character, for example, is a solemn ninja called Gozaruchi, whose defining trait is shyness because I rarely remember to take him outside. The Uni also has motion sensors so users can steer the screen from side to side while playing games, which Jadeja points out is similar to old-fashioned pinball mazes. While it retains the same high-pitched digital beeps as the Original and the animation is still pixel art, there are additional sounds and much more detailed graphics: you can see the characters blush or look surprised, for example.

Inside the Tama mall, where users can pick up items to personalise their character or home (image: Bandai-Namco).

Despite some of these key similarities, it feels like the Uni motivates me to care for it by dangling a carrot, while the Original uses the threat of a stick. This feeling is underscored by the fact that the Uni doesn’t even feature a discipline button – in this model, it only matters that my Tamagotchi is kept happy and full. Due to its superior animation and world-building, the Uni feels like both a pet and a place: a pastel-coloured universe where I can hang out away from whatever dull task I’m doing in real life, offering a reprieve that feels similar to going on social media. Accustomed as I am to algorithms seducing me into a never-ending scroll, I realise that I was unused to the Original’s barefaced manipulation, and how little it seemed to offer me in return. Gozaruchi even models this addictive behaviour back to me: at around 7pm each day, he automatically starts playing on a tablet like a bored child at the airport.

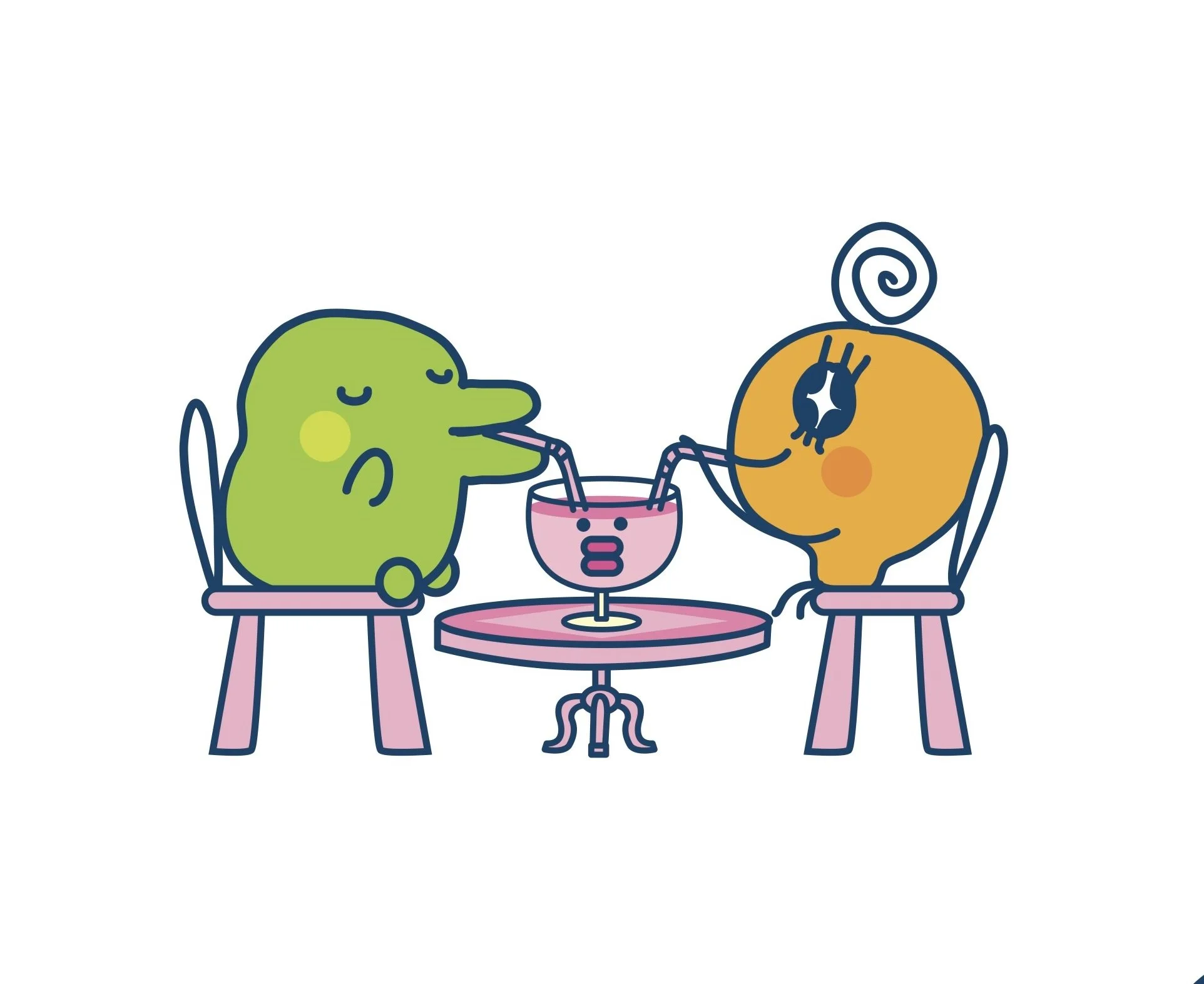

The spatial aspect of new technologies is highlighted even further by the Tamaverse feature. Inspired by ideas of the metaverse, Gozaruchi can put on a virtual reality headset and quickly arrive in a parlour where he is greeted in various languages by the characters of other Tamagotchi users. “We tried to make a device with lots of new features to explore and connect in ways that are relevant for the times we’re living in,” Jadeja says. Each character represents a real person who is tuning into the Tamaverse at the same time as me; but in order to ensure younger users can play safely without needing parental supervision, we can’t do anything more than automatically greet each other in our native tongues. “We wanted to make sure it is accessible for older fans, but still totally safe given that you potentially have six year olds playing as well,” Jadeja says. My favourite part of the Tamaverse is taking Gozaruchi on dates: after selecting a match from a Tinder-style deck of characters, my ninja gets to sit with them briefly in a jazzy art deco-style bar or a peach-toned café.

But Alice tells me that she enjoys how austere the Original is. “When kids watch too many cartoons, they become a bit numb, and just want more and more,” she says. “But Mélodie doesn’t get like that with the Tamagotchi, it’s different. You feed it and play with it, see that it’s OK, then put it down.” The Tamagotchi revival has also coincided with the rise of using retro mobile phones, or “dumbphones”, as a way to fight social media addiction. The first ever mobile phone I owned, the Nokia 3310, was re-released in 2017; I still have vivid memories of its buttons rubbing under my thumbs like jelly sweets. It strikes me that I have very few sensory impressions of my iPhone; its smooth touch screen offers me a seamless window into another world.

Due to the Tamagotchi Uni’s superior animation and world-building, the device feels like both a pet and a place which users can visit (image: Bandai-Namco).

Everything in the Uni gives the impression of sentience: all the furniture has Tamagotchi-style faces with little eyes and beaks, including the bath and the toilet, and outside in the garden there’s a green hedge with a face who likes to flirtatiously nuzzle Gozaruchi and shimmer with hearts. The emotional attachment that Tamagotchis engender in humans comes from this same phenomenon – attributing a life-force or essence to inanimate objects, otherwise known as animism.

In Millennial Monsters, Allison suggests that the animism of Japanese traditions, such as the indigenous religion Shintoism, shaped the design of Tamagotchis, and in an article about human relationships with technology for Emergence Magazine, ecologist and philosopher David Abrams points out that animist beliefs are actually common to most indigenous cultures. “The instinctive experience of reciprocity or exchange between the perceiver and the perceived lies at the heart of all human perception,” he writes, arguing that we have an innate tendency to view our surroundings as full of life. Coupled with a new and unfamiliar technology, this inclination meant that some children in the 90s struggled with the mortality of Tamagotchis; in 1998, CNN reported that a pet cemetery in Cornwall had fenced off a section for electronic pets, where owner Terry Squires carried out burials for Tamagotchi lovers from Switzerland, Germany, France, Canada and the United States. The feature was accompanied by photos of solemn children with mullets holding tiny coffins.

The Original Tamagotchi’s death screen features a black skull, while other models incorporate gravestones (image: Bandai-Namco).

“When [the Tamagotchi] first died, we hadn’t told Mélodie that it was going to come back, and she was really upset, really, really distraught,” Alice says. The Original’s death screen is pretty distressing: a black skull hovers over the character while the device emits beeps that sound like a life-support machine slowing down. No matter how many buttons you press, there’s nothing you can do, and eventually it turns into an angel and floats off the screen. But the poignancy of this saga is dulled once the Tamagotchi is reset and a new egg instantly appears on the screen; once Mélodie realised the cycle of care could start all over again, she was no longer affected.

After helping to raise around eight characters with Mélodie, none of which have lasted beyond ten days, Alice’s heart has grown weary. “I’m a bit more reluctant to kind of love it, or make an attachment, because I just think, well, it’s probably going to pass away anyway,” she says. Alice believes that if it was easier to keep the device alive for longer, then even greater attachments could be formed. But as Allison points out in Millennial Monsters, “making the toy labour-intensive from the minute it hatches was part of Yokoi’s design, intended to make players attach immediately to their ‘pets’”, a feature which privileges forming an instant attachment over sustaining a long-lasting one.

“Tamagotchis show that care can only be briefly manufactured through programming, while soft toys demonstrate the staying power of love that is given freely.”

When I ask Alice if the Tamagotchi is Mélodie’s favourite toy, she immediately says no. “She goes to bed with a couple of soft toys and I think these are like, her top toys,” she says. Soft toys also invoke a sense of animism: a 2007 study by psychologists at the University of Bristol and Yale University concluded that children become attached to soft toys or blankets they sleep with because they believe they have “a unique property or ‘essence’”. Unlike Tamagotchis, this essence can’t be replicated: when offered copies of their beloved toys in the study, the vast majority of children distinguished their original objects from doppelgängers and stayed faithful to them. And although they can be mangled or lost, soft toys don’t threaten expiration – in fact, researchers at VU University Amsterdam even found in a 2013 study that cuddling a soft toy can help alleviate people’s anxieties around death.

I would never look at a new soft toy with pristine fur and think it had an essence, but when I remember the black horse with a diamond on its forehead that was large enough for me to spoon as a child, and my brother’s well-loved sock-puppet named Johnny, it’s hard not to feel like they soaked up a part of us, subtly animated by the daily embrace of our sleepy arms. An article from design trends magazine Hype&Hyper suggests that designing animistic products could be a potential tool for avoiding overconsumption by making people feel more attached to their possessions, and this is certainly true for soft toys, which retain their charm long after their beauty fades. But when it comes to technology, this theory doesn’t seem to hold water. “We become attached to our electronic devices not for their own sake, but for what the technology they contain enables,” Hype&Hyper writes. “Our cherished phones will soon be replaced by a newer and smarter model, and the old one can go in the trash.” Tamagotchis show that care can only be briefly manufactured through programming, while soft toys demonstrate the staying power of love that is given freely.

Characters in the Tamagotchi Uni are able to go on dates and get married, a move which ends the lifecycle of a character without having it die (image: Bandai-Namco).

As befits the Uni’s softer approach to parenting, my ninja doesn’t have to die. At the end of every date in the Tamaverse I am given the option to let Gozaruchi propose and, once married,[1] he will disappear. After a few days I tire of caring for him, and when I see his health starting to deteriorate, I finally allow him to marry a pudgy, starry-eyed character wearing a panda hat. “I will protect you with everything I have!” he proclaims, and she responds with fluttering hearts. Fireworks explode, and they ride off into the sunset in a white car with a duck beak while other characters throw confetti. Almost instantaneously, an egg rolls on to my screen, which my good-for-nothing son has left me to raise.

[1] Tamagotchi models that allow characters to get married do not permit same-sex bonds, even though the characters themselves often appear quite gender-neutral. Fans, however, have rebelled against this heteronormative programming, with multiple TikTok videos and a guide on Inverse about how to raise a queer Tamagotchi.

Words Helen Gonzalez Brown