Personalised Insights and Core Functionalities

Technology for tracking menstruation cycles, which has existed for centuries, enters the app era (image: Clue).

The rise of the app-based period tracker seems to take something relatively simple – counting the days of a menstrual cycle, an average total of 28 varying from person to person – and turn it into something emotionally fraught, personally invasive and inexplicably costly. When applied to the female reproductive cycle, networked digital technology does not change the phenomenon at hand, but it does turn it from an embodied process that society still encourages us to experience as squeamishly private to a source of data extraction. Such harvesting could very well violate ethical as well as legal boundaries, and have far-reaching social consequences.

Of course, period trackers predate the smartphone and the internet. Prehistoric human artefacts such as the Lebombo bone, a baboon fibula with 29 notches carved more than 43,000 years ago, have been described as possible lunar-calendar trackers, although that temporal phase could have many other biological and cultural meanings attached to it. Closer analogies to today’s apps can be documented in the few dozen patents for period trackers – designed as calendar wheels, mechanical devices or electronic gadgets – that were submitted from the 1930s until the early 2000s. Similarly to contemporary options, these trackers grappled with issues of privacy, accuracy and purpose. Most assumed, however, that the user was interested in bringing on pregnancy rather than avoiding it. It was not until 1961, in Wilbur Dickinson’s Menstrual Cycle Indicator patent, that the focus on fertility expanded to include the aims of personal convenience: “birth control may be effectively practiced, vacations may be properly scheduled, etc.” Most patents also assumed that such information would embarrass the user if it were publicly broadcast: John Cwiekalo’s 1941 Computing Device hid the words “Fertile“ and “Sterile” under a disc discreetly labelled “‘Menstruation’ only”, while Emil Josef Biggel’s 1993 Menstrual Cycle Meter was the first to offer password protection and was “outwardly designed to look like an ordinary calendar and timer in order not to invoke any embarrassment”. The only other people who could be privy to the user’s readings were their doctors or husbands, which brings us to a third assumption: that users of the trackers could only be cisgendered, heterosexual women who were sexually active solely within the boundaries of marriage.

These issues are obviously entangled with design. Take something as basic as colour. Red, green, yellow, blue, pink, maroon, purple, grey – these all have complex associations with both bodily discharge, conception, pregnancy, risk and safety. In William Rahn’s 1938 patent for a Cycle Calendar, coloured cellophane was used to indicate the fertility period in green and the menstruation period in red, but Martin Lichter’s 1945 Calculating Device made the interval of possible conception “advantageously conspicuously marked by being colored red”. Other patents used more neutral symbols. Joseph Jackson’s 1998 Personal Fertility Predictor used a star for the menstrual cycle, a plus sign for ovulation, a triangle for decreased fertility and a square for increased fertility.

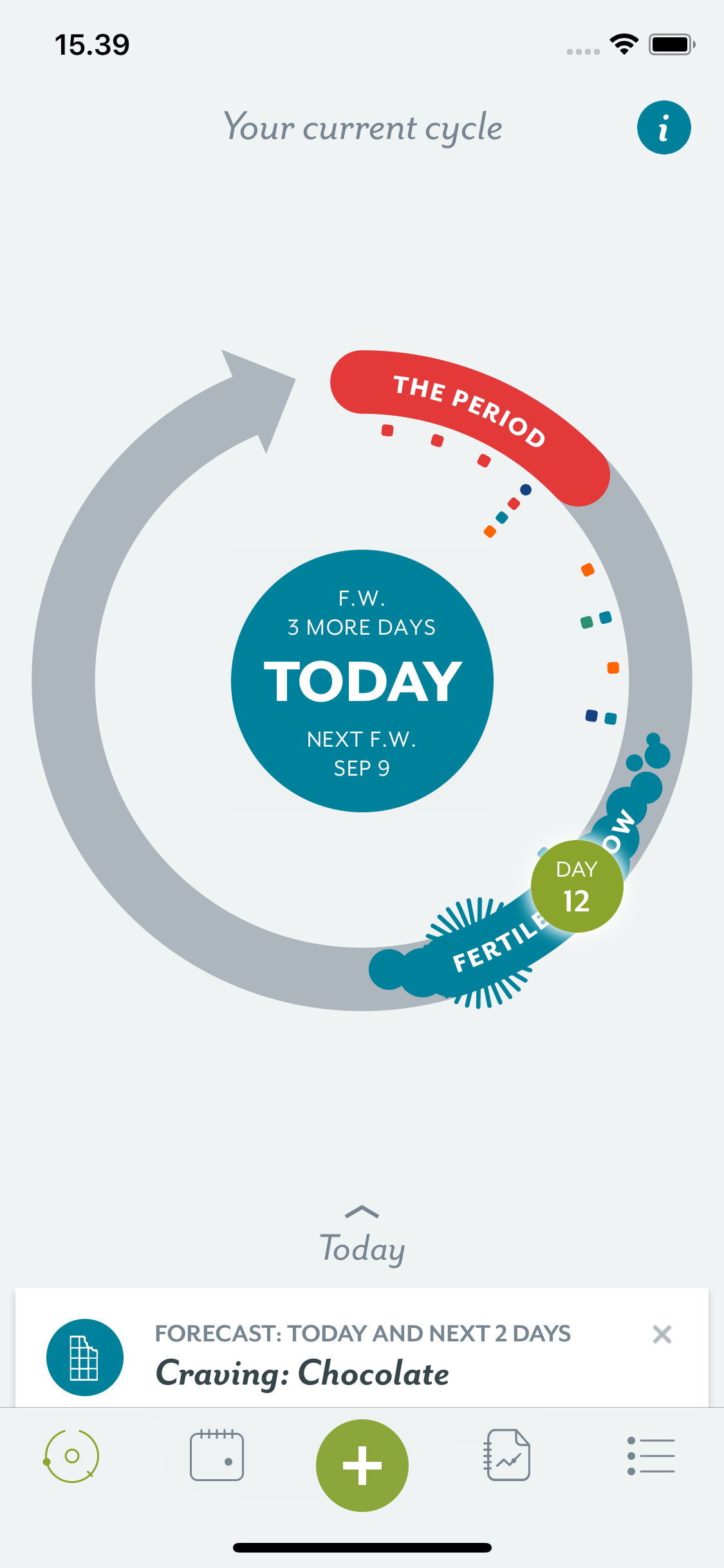

Circles are a prominent design feature in period-tracking apps (image: Natural Cycles).

If today’s apps have different aesthetic properties – attractive colour palettes, minimalist layouts, universal abstract iconographies – this is not indicative of any real improvement in the underlying mechanism. Rather, it seems that the assumed user – a cis woman between adolescence and menopause – is being reconstituted more clearly as a consumer: someone to entertain and flatter as much as to inform, and someone to entice into buying premium services. Apps such as Flo, Period Tracker, Clue, Eve, Natural Cycles, Spot On and Femometer use pink, red, or maroon in their icons but tend to avoid design decisions – such as the traditional green and red system – that might suggest a value judgement on menstruation, fertility or inability to conceive. To indicate calendar phases, they stylise dates more subtly with circled numbers, boldface type or colour fills in grey or turquoise. Their logos often incorporate flowers, circles, or both, invoking notions of cyclical time or the finite linearity of living creatures – birth and “blossoming” anticipating inevitable mortality. Inside the apps, symbols such as drops, hearts, suns, smiley faces, babies and animals are used to refer not only to periods and pregnancies, but also to lifestyle choices and body statistics, including physical pain, psychological changes, sleep patterns, exercise, sexual activity, nutrition, hormones, birth control, medication and more.

“No method of electronic storage is 100% secure.”

One outlier to this standard schema is Cube, an app made by Flask, a studio founded in 2013 by the Japanese software engineer Hideko Ogawa and product designer Takako Horiuchi. With its three-dimensional pixels and single-colour themes – blue is the default, but other colour options can be purchased – Cube looks like a cross between the game apps Threes! and Monument Valley. It is also a major outlier in three other respects. First, it does not ask for any data bar the starting date and length of your cycle. Second, it does not offer any advice based on a given moment in the calendar. Third, it does not require profile registration or host any data beyond the local device. (Its privacy policy does remind users, nevertheless, that “no method of electronic storage is 100% secure”.)

Cube’s differences reveal a critical fact about other period-tracker apps: they are less functional tools for personal health than Trojan horses for the capture of personal data. Considering the obsession with innovation among high-tech firms in the past decade, there is a remarkable lack of new patents for period tracking since the rise of algorithmic computing: less than 10 in the last decade and only a few of them mentioning artificial intelligence. But what is there to innovate? The calendar method has been common knowledge for millennia and other techniques for estimating cycle position – such as measuring the body’s basal temperature – were already established in the 20th century. The computer programmers behind today’s period tracker apps have very limited means to make their predictions any more accurate than the tools that already exist and thus have no new intellectual property to claim. This is not entirely surprising, given that human beings evolve rather slowly.

Data on women’s fertility is a valuable asset to online advertisers (image: Clue).

This conceptual dead-end has significant implications for the way period-tracker apps work, because investors in technology are less interested in utility than they are in profit. To go beyond the algorithmic processing of self-reported data on cycle length (and other personal conditions) would entail medical tools or devices, such as vaginal thermometers and chemical reagents for vaginal discharge. By contrast, apps want to be borderless, effortless and continually optimising their service. Medical instruments would be anathema to this – subject, as they are, to governmental approval, insurance coverage, physical manufacture, distribution, legal accountability and customer service management. But period-tracker apps do pose financial opportunities in other ways – because, according to a Financial Times report, identifying a pregnant woman has equivalent value to knowing the age, sex and location of as many as 200 people in the eyes of online advertisers. Presumably, women trying to conceive and women trying not to get pregnant are also valuable financial assets.

Often, the details these apps request from users have only the most tenuous connection to fertility. In the course of researching this article, I have volunteered personal information about my sex drive, masturbation, condom usage, how easy it is for me to achieve orgasm and whether I am sexually active during my period. I have provided data on my weight, acne, breast tenderness, cramping and digestive condition; my feelings of guilt or depression, stress levels and obsessive thoughts; the texture and colour of my vaginal discharge; the height, openness and firmness of my cervix; my travel patterns, alcohol intake and food cravings; my ethnicity, education level and my mother’s education level.

“It’s great that the discomfort that you experience doesn’t really affect your life.”

While providing such information to Flo, I was offered in-app dieting advice and dubious trivia (such as the unverified claim that “cycle and period length[…] are unique for women of each ethnicity”), but when I sought information about cramps – the only thing about periods that really bothers me – I received surprisingly little useful feedback. Less than half of the apps offered advice about the range of cheap, over-the-counter medication that can quickly eliminate such pain, from non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as ibuprofen or naproxen, to hyoscine butylbromide (Buscopan). Instead, they suggested hot baths (I don’t have a bath) or orgasm for pain relief (not the most pragmatic option for those at work, taking care of children or the elderly, or in transit). When I reported to one app’s chatbot that I experience moderate pain from cramps, it responded: “It’s great that the discomfort that you experience doesn’t really affect your life.” It only gave me one option to reply: a winking emoji.

Period-tracker apps are thus faced with a paradoxical challenge: to extract as much personal data as possible without breaching regulations on medical practice, personal rights and privacy. This leads to some bizarre formulations in their terms and conditions. First, most insist that they should not be used for contraceptive, diagnostic or other medical purposes and claim no responsibility for personal injury or damages that could result from their use. Femometer “does not guarantee the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any content” it provides. Glow demands that the user be a resident of the United States and a patient of a healthcare provider that offers GlowCare – requirements that seem too important to bury in the fine print.

Period tracker apps must not breach regulations on medical practice or privacy (image: Clue).

Second, most trackers prohibit users from using the in-app community services to advertise for commercial activities (which the app itself may be engaged in) or, in the case of Cycles, “contribute to propaganda, religious and/or political views”, which seem impossible to extricate from any dealings with pregnancy, infertility, contraception and abortion. Cycles allows you to share information about the phases of your menstrual cycle with a partner, though it implies a framework of monogamy: “You can invite as many people as you like, but only connect with one person” – let’s hope the right one responds. Similarly, Femometer invites users to log information about assisted reproductive technology (ART) used to address infertility, but refers to this as “Artificial Insemination of Husband”. (The app, made by the Hangzhou-based company Bangtang Network Technology, may reflect standard requirements for ART in China’s national medical system.)

Third, most apps prohibit children under the age of 16, in some cases 18, from using them. Flo has particularly Byzantine requirements: users must be at least 13 years old to use the app, but in the EU they must be over 16 (a consequence of GDPR), and the online courses are only for those 18 years and over. Inexplicably, some apps nevertheless encourage users to input the names and ages of their newborn children or log the development of their foetuses. They still collect data about the very young while excluding adolescents – some of whom get their period as early as age 10, and are the very people who often need the most advice on their periods and for whom the awareness of pregnancy risk is most crucial. In other words, these age restrictions shut out those for whom the service might be most useful. Even worse, some apps, such as Cycles, encourage parents or guardians of under16s or under-18s to contact the developer if they suspect their children have used them.

“If you disagree with the collection and processing of this data you should stop using Cycles, delete your account and uninstall the application.”

For over-18 users, the terms of service make divulging personal information unavoidable. “By using Cycles,” for example, “you agree that all of the personal data provided by you is accurate and up to date.” While they claim such information is not publicly accessible, they also explain, “we aggregate and de-identify certain information about our users to use for business purposes.” Natural Cycles claims that personal data will be held for three years and asserts ownership of user information as possible transferred assets in any future business acquisitions or mergers. In some apps, users can also opt in to community features to compare their cycles and symptoms to those of other users anonymously, or consent to provide their data for “academic and clinical research purposes”. Information is shared “where necessary in the public interest, such as most common symptoms related to menstrual cycles,” as well as for the “legitimate interest” of the app developers and their business partners.

“We do this to understand your needs, improve Cycles, deliver personalised insights and other core functionality.” Information such as the frequency of app usage or symptom reporting, IP and email addresses, devices and more is combined with external data connected to the user profile obtained from the company’s other apps or third-party suppliers. “If you disagree with the collection and processing of this data you should stop using Cycles, delete your account and uninstall the application.”

Words Tamar Shafrir

The apps discussed in this essay are available to download from the Apple App Store and on Google Play. Some contain in-app purchases.

This article was originally published in Disegno #25. To buy the issue, or subscribe to the journal, please visit the online shop.