No Fidget Spinners

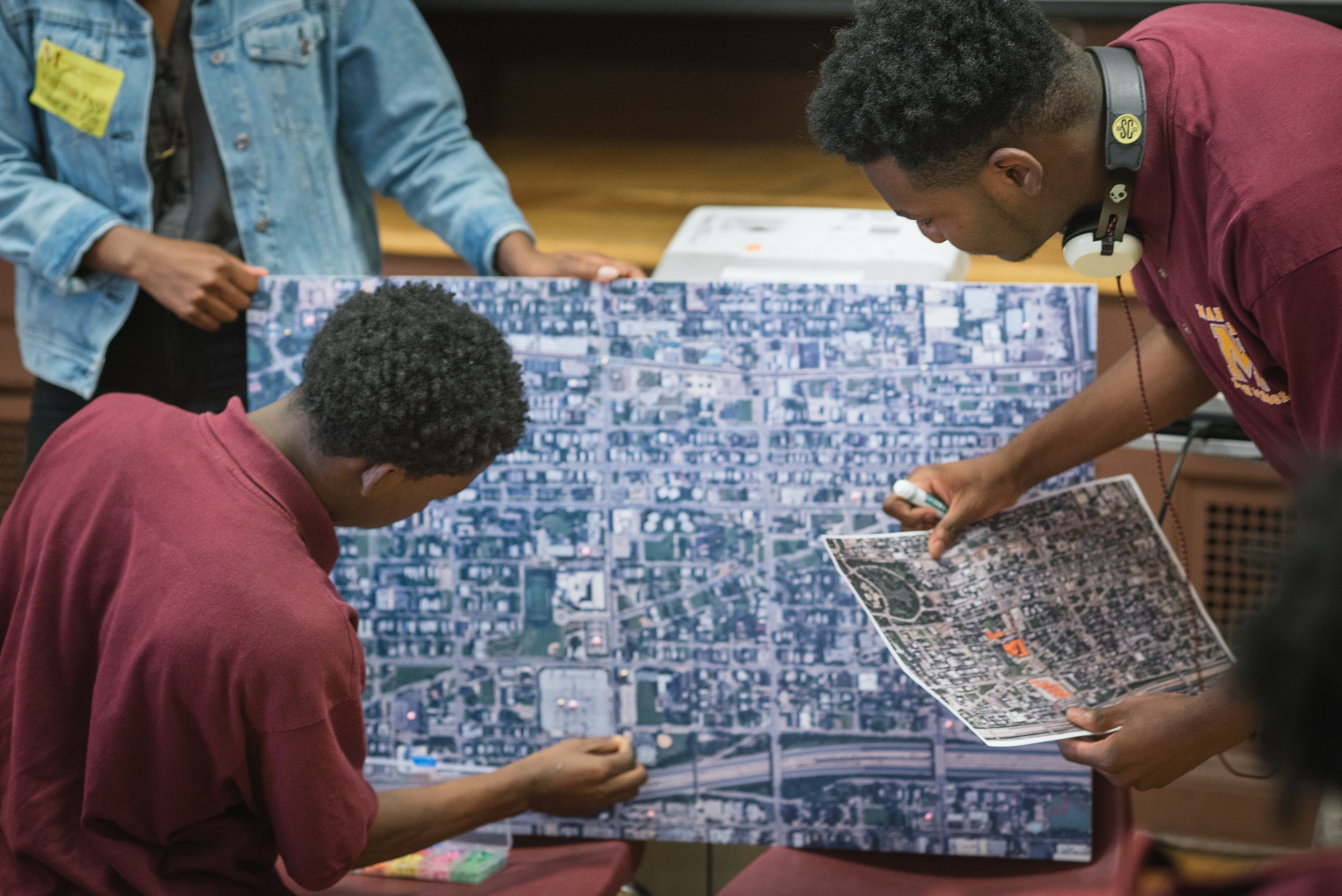

Image courtesy of Mobile Makers.

Attending the Virgil Abloh exhibition Figures of Speech at Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art in 2019, I was not very moved by the work. While I could catch the genius of his approach in glimpses – most powerfully in his early work, in which he wielded his hunger, youth, and Blackness like a knife – the later pieces felt too shaped by a palpable desire for monumentality. But as fashion critic Rikki Byrd pointed out to me, what distinguished the exhibition was who it brought into the museum: huge numbers of young people – particularly young men – came to the show in droves to pay homage to work that moved them. Recalling the streetwear-clad teens and twenty-somethings intently studying Abloh’s creations, I can think of no recent visual artist who touched so many under the age of 25.

Maya Bird-Murphy, too, knows something about how a passion for design can light up a certain kind of kid moved by the look of things, be it a sneaker or a planter, a skyscraper or a public park – even if they might never use the word “design” to describe this passion. Mobile Makers, the organisation she founded in 2017, runs design-focused workshops in Chicago and Boston where students from diverse social, economic, gender, and racial backgrounds learn not just what design is, but what it can do and how to start doing it themselves. When I visited a Mobile Makers workshop at the iconic Wrigley Building in the Chicago offices of architecture practice Perkins & Will, what most lit Bird-Murphy up that day (and, soon enough, me as well) was the prospect of sneaker designer Chelsea B attending a design summit that Mobile Makers is hosting in the fall. Below us lay the Magnificent Mile, Chicago’s downtown crown jewel and the recent subject of much panicked theorising about the crisis of American downtowns at large, given the number of retail vacancies and uptick in crime. But Bird-Murphy’s vision aimed elsewhere, as she imagined how to bring the city to Mobile Makers’ West Side headquarters in Humboldt Park to rethink design and architecture. Not for the last time in my stint with them, I sensed that the future of cities – and who designs them – was being radically remade by Mobile Makers, one workshop at a time.

One of the organisation’s mobile workshop spaces (image: courtesy of Mobile Makers).

While Mobile Makers has received much coverage through the architectural press, it’s important that architecture is not in the organisation’s name, nor its named priorities. Despite her personal love for architecture, Bird-Murphy “can see it for what it is”– a profession that is often ego-filled, competitive, performative, and doing little to solve the world’s most pressing problems. And yet her frustrations with architecture come from her deep awe for what it can do. “Architecture is life and death,” as she says. “People are dying and architects have every skill needed to do something about that.” She particularly hates it when architects claim to be powerless, fashioning themselves as mere cogs in the machine run by clients and capital. Mobile Makers instead approaches architecture as a set of superpowers that can help solve just about every problem imaginable. Part of their mission is to arm a new generation of residents and makers with the awareness of this power to better harness it for themselves and their communities.

But while Bird-Murphy cares deeply for architecture, she is careful to disaggregate her personal penchant for it from Mobile Makers’ commitment to many forms of design. The “mobile” in Mobile Makers marks the range of design practices their workshops teach, but also their multi-site strategy. Bird-Murphy began the organisation out of a delivery van she converted into a classroom, enabling her to hold workshops anywhere in the city. And even with their recent move into a new permanent location, Mobile Makers remains committed to running workshops in multiple places. When working in schools, for instance, Mobile Makers can reach kids who might never think to sign up for a design class, while at Perkins & Will, teens from across the city get a taste of what it’s like to work in a global firm. Bird-Murphy eventually imagines Mobile Makers expanding to support multiple tracks of design interest, from introducing kids to the concept, to helping students assemble portfolios and research design schools.

Image courtesy of Tom Harris Photography and Mobile Makers.

At Perkins & Will, the Form Work workshop that Mobile Makers ran takes place adjacent to what I can only describe as a shrine to diversity, kitted out in masquerade masks and Chinese calligraphy. Photographs of staff celebrating Diwali sit on shelves next to framed printouts of the company’s “JEDI strategies”, which stands for Justice, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion. A nearby placard touts the firm’s fellowship opportunities for underrepresented students, while another proclaims, “We believe diversity drives innovation and inclusion sparks creativity.” Holding the workshop in the shadow of these declarations feels a little on the nose, but the kids pay it no mind as they work intently on their own plans to reimagine nearby DuSable Park. One student, for example, works on a model for a new Native American museum incorporating elements of indigenous design; another envisions a public space that could serve those in search of music and quiet simultaneously (she was particularly keen to stack different shades of plastic in her model to conjure a rippling pond). This diverse array of students have travelled from across Chicago and its suburbs for these sessions. To enter this architectural mecca, a guard in the lobby checks their IDs and their names off a list. The tension between this inaccessible space proclaiming its accessibility seems to be part of the lesson; this is one route that design can take amongst many others.

As the kids worked on their models, Bird-Murphy and I chat about the uptick in interest that Mobile Makers received from architectural firms after the murder of George Floyd. She describes being flooded by requests from firms to speak, hold workshops, and generally buttress their various JEDI, DEI and D&I commitments. But this surge has since turned to a trickle, Bird-Murphy notes, a fact that is unsurprising if no less disheartening; I experienced a similar surge and decline of interest in engaged work by firms and schools in my roles as both a scholar of race and architecture, and faculty director at Arts & Public Life, an initiative that is similarly committed to introducing youth in Chicago to civically-minded design and arts practices. Such predictable patterns only reinforce that “changing things from the inside doesn’t work,” Bird-Murphy insists. Hiring a few Black or Brown designers at majority white firms will do little to transform the demography of architecture, never mind its mission and approach. Mobile Makers is, instead, an effort to change things from multiple outsides – outside of firms, outside of architecture alone, from the literal outside through workshops hosted in parks and parking lots, and outside and beyond the racial homogeneity dominating most architectural spaces.

Image courtesy of Mobile Makers.

Despite the downtick in interest from firms, Mobile Makers remains busy. In a year, they can easily run 150 workshops, and demand from schools, organisations, and students remains fierce. Unlike the monumental digs of Perkins & Will, the group’s Humboldt Park offices feel lived-in and decidedly local. Spilling out from every corner of their large loft space are a gaggle of past projects held together with glue, decorated with markers, or fabricated in-house in plastic. This space will soon come to look a bit more firm-like. Bird-Murphy shares with me the renderings for the imminent renovation that will separate their current large undifferentiated space into distinct sections including a lobby, classrooms, a conference room, and a library (architecture books are expensive and hard to access, she reminds me). While I’m excited for what the space will become, I’m no less charmed by the space as it is. As Bird-Murphy narrates some of the past projects on display, we admire a cardboard structure representing a design for a new backpack made for firefighting, while nearby sits a “Purring Station” meant to house a robot cat. By the 3D printers we see remnants of mini-planters from workshops past. Kids come to know the spaces here, allowing them to feel ownership over both what they make and where they make it.

But even as this space in Humboldt Park is refurbished, the core of what’s taught here will remain the same. Bird-Murphy describes introducing students in workshops to the concept of design by starting with their own sneakers or bedrooms. I can’t help but think of my own younger brother who, as a teenager, braved long lines for sneakers or the latest Apple drop. Though he would have never described himself as someone “into design”, he devoted precious time and even more precious resources (he worked at a local diner after school to afford these luxuries) to these objects whose every curve he had studied.

Image courtesy of Francisco Lopez de Arenosa and Mobile Makers.

Mobile Makers introduces design to students as a practice that already touches their lives. And in the same way that choir club and team sports forge communities of like-minded doers, Mobile Makers seeks to facilitate forms of belonging around design. The coming renovations will allow for more hanging out space so kids can geek out together over this shared passion. The organisation’s location in Humboldt Park – a historically Puerto Rican neighbourhood that is now being gentrified – is also key to the community they hope to magnetise. White families are willing to drop their kids off here, Bird-Murphy notes frankly, even as the neighbourhood remains majority Black and Brown. Workshops bring together students who might not otherwise meet, especially within the still deeply segregated city of Chicago.

In addition to its commitment to both roving and rootedness, Mobile Makers is grounded by its principles. Bird-Murphy is not interested in teaching design for design’s sake or fetishising design as an autonomous art object to be worshiped in isolation. The things students make in Mobile Makers workshops must have use and meaning. Projects should be aimed toward transforming communities, be it in the form of self-watering planters or public structures. One rule for Mobile Makers’ 3D printing workshops proves illustrative: no fidget spinners. “We’re not making shit just to make it,” Bird-Murphy underscores. Every workshop connects back to the world, while still making room for fun and beauty and meeting students where they are. Given that Bird-Murphy’s training is in architecture (she has an MA in architecture from Boston Architectural College), her approach to curriculum-building has evolved through trial and error over many long hours. When creating new workshops, her team generally begins with the contours of a studio project and then boils it down to its essentials. Unlike high school architecture programs that tend to focus on technics, Bird-Murphy has found that such a rigid emphasis can turn kids off design before they even start to grasp its power. “Teaching a high schooler to work to scale,” she insists, “is counterproductive.” She instead starts by asking what is actually relevant to the lives of young people and builds projects and prompts from there.

Image courtesy of Francisco Lopez de Arenosa and Mobile Makers.

I caught a glimpse of this strategy’s pay-off when talking with a student at the Perkins & Will workshop. Asked what session she most enjoyed, she described an activity in which they transformed a sheet of paper into a functional form by bending and curving it, off-handedly referring to this as an exercise in which “form meets function.” This insight was gleaned not from reading Louis Sullivan or studying architectural textbooks; it came from experiencing it herself while making a structure for a park she observed, studied, and then reimagined. Her keenness brought to mind the young men I had earlier observed worshiping at the altar of Virgil Abloh, as well as my own sneaker-and-tech-loving little brother – each of whom seemed to be finding new ways of living, touching, and feeling in and through design, even if that was not yet a term they used. Mobile Makers helps students find and wield the language of design, not for recitation’s sake, but to use it for themselves, their communities, and – if they decide to share their talents with the broader world that has so frequently refused to share with them – to solve the life and death problems that design is inherently equipped to transform.

Words Adrienne Brown

This article was originally published in Design Reviewed #2. To buy the issue, or subscribe to the journal, please visit the online shop.