Kazam!

The second of two Molded Plywood sculptures with a hand to denote scale (image: courtesy of the Eames office).

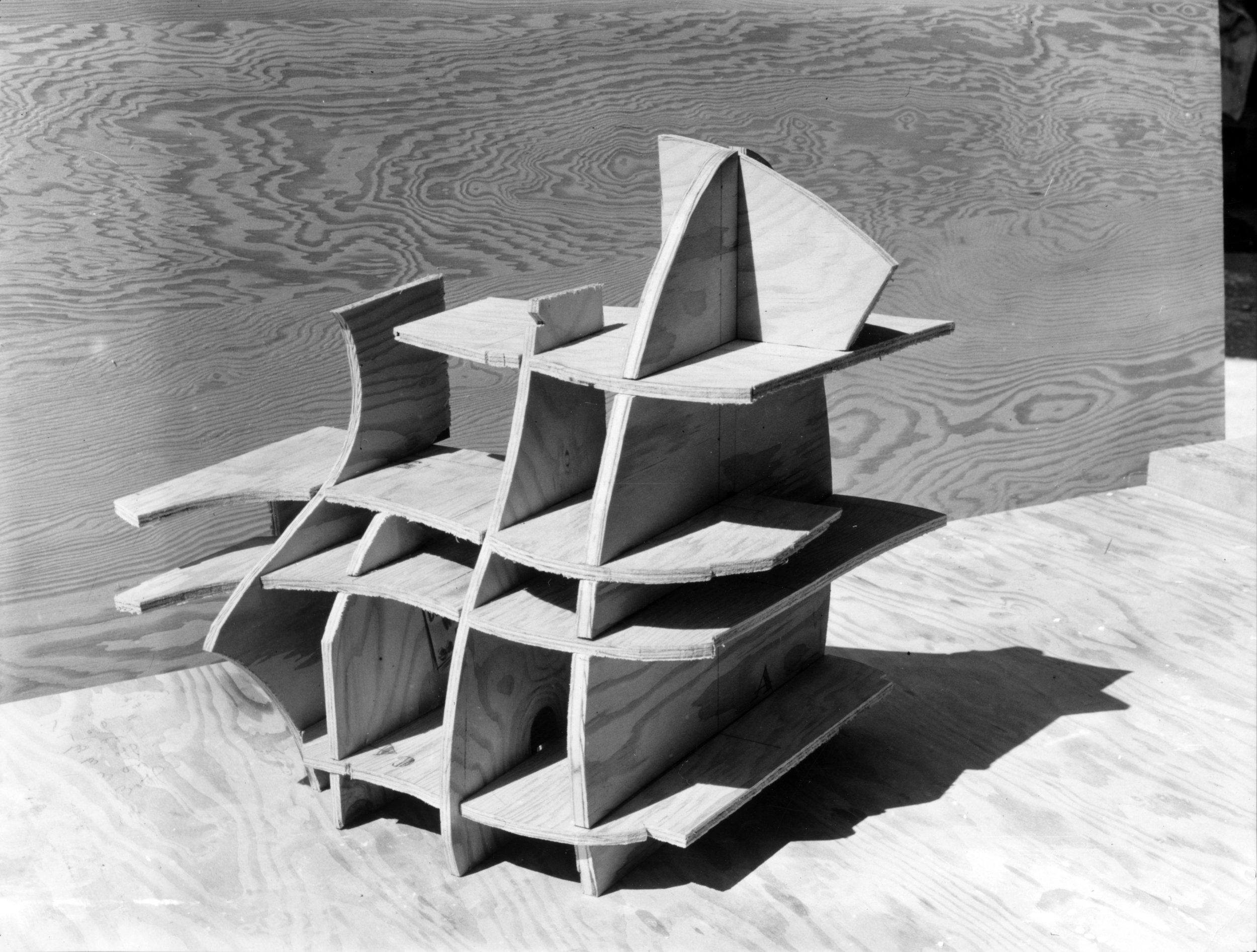

In 1943, Charles and Ray Eames produced two plywood sculptures. Full of rolling compounds curves and contortions, the sculptures showed the promise of the designers’ Kazam! machines – homemade devices that they had created to enable their experiments in moulding plywood.

The sculptures were exhibited in 1944 at MoMA in New York for the museum’s Design for Use show, but their role in the Eameses’ practice has often been overshadowed by the designers’ subsequent work with moulded plywood furniture, such as the 1945 LCW and the subsequent wider Molded Plywood Group. The sculptures were one-offs – rare artisanal works that slip into the margins of history when seen alongside the design for industry that followed.

Now, however, the Eames Office is returning the Molded Plywood Sculpture to the centre of the Eames story. To mark the office’s 80th anniversary, a limited edition of 12 plywood sculptures has been created according to the Eameses’ original methodology. The edition is based upon the version sculpture currently owned by the Eames Office; the second sculpture came up for auction in 1999, and is currently held by the Vitra Design Museum.

Charles and Ray Eames, with Eames Office staff members posing on the staged set for their 1948 MoMA “International Competition for Low-Cost Furniture Design” entry (image: courtesy of the Eames office).

According to Eames Demetrios, Charles and Ray’s grandson and director of the Eames Office, the sculpture represents a pivotal turning point in the design career of the Eameses. For Demetrios, the extreme curves of the sculpture were not only a mode of artistic expression, but also a form of material experimentation that enabled the later works within furniture. Meanwhile the complexity of the sculptures also demonstrates the growing mastery of the material and its methodology that the designers developed through their work producing plywood splints and airplane fuselage parts for the US war effort.

The sculptures required consummate engineering to be possible. The production was a time consuming, hand-craft process, in which between eight and twelves sheets of ply were cross-layered as according to the sculpture’s need for rigidity and suppleness at different points. The Kazam! machine would subsequently mould the form over the course of a four-to-six hour process. Even with the benefit of a 3D scan of the original sculpture, and a one-year research process, the new edition of the sculpture is still technically challenging to produce.

To discuss the sculpture, its new edition, and the design’s significance to the Eameses’ work, Disegno spoke to Demetrios over Zoom. An edited version of the resulting conversation follows below.

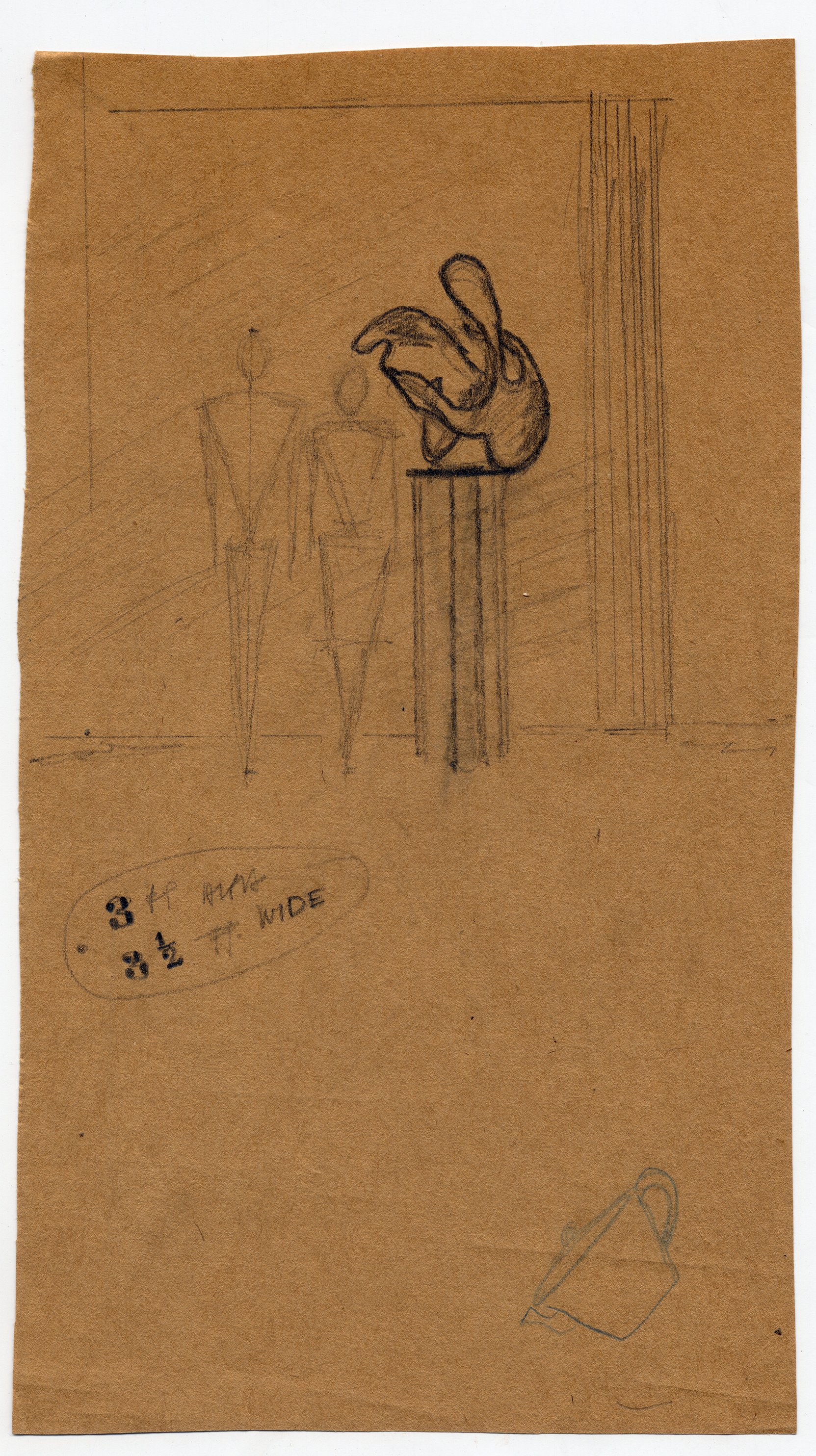

A sketch by Ray Eames of the human-to-sculpture ratio for an exhibition in 1943 (image: courtesy of the Eames office).

Disegno What’s the experience like of delving back into the Eames Office’s history? That kind of research must always be interesting, but it must be a strange experience with additional resonances given that it’s your own family you’re investigating.

Eames Demetrios There are five kids in my generation and we all had our own experiences of Charles and Ray, which drove us to want to participate in the studio. I made a film about closing the office [901: After 45 Years of Working, 1989] because I'd always loved that space. Meanwhile, Ray had asked the family to be sure to take care of the house and make sure that things were made right: so in the end, that's kind of an IP question. So I thought, gosh, if we're gonna do this, we really need to know more. So I did over 200 hours of interviews. And I think because I was a grandchild, a lot of people were willing to have really great conversations with me and I learned the deeper ways that [Charles and Ray] were in fact remarkable people. They weren't perfect people, but that is much more interesting anyway. They had passions, they could be very intense when they were trying to get things exactly right. But they were also amazing and compassionate. We’ve made a conscious attempt to navigate that and see that some of their stories are recovered.

Disegno Did Charles and Ray leave specific instructions around how they wanted their legacy to be managed? Because it's not just a case of making sure everything goes to museums, for instance. A big part of the work that you do is in trying to extend their legacy and carry it on. But that's a difficult thing to interpret in terms of what feels like a positive continuation within the spirit of and respectful towards their work.

Eames There's not a particular manifesto. Charles died very suddenly, but Ray had a lot of conversations with our mother, in particular, because she was trying to figure out exactly how this should work. In the the end, it came down to seeming like the best way was to make sure that the family felt empowered to do what it felt was correct on these things, because you can't write a roadmap for everything. If people think we've done an imperfect job, they have the right to think that, but I feel pretty proud about what we've done.

The first of two compound curve plywood sculptures created by the Eameses in 1941-42 (image: courtesy of the Eames office).

Disegno So where does the sculpture fit in? When did you start looking into that and consider bringing it back?

Eames We've been thinking about it for a long time. It's an object that is incredibly beautiful and important, and it captures the complexity of Charles and Ray in the sense that they both brought their capacity as artists and technological innovators to this object. I've always thought that it was extremely important in their story and that its blend of art and technology almost perfectly expressed them. Every time the original has been at a show, we grandchildren have taken the chance to look at it and treasure it. Then, probably more than 10 years ago, another sculpture appeared and a couple of journalists asked me, “Are you bummed out that you don't have the only one?” Actually, I think it's great, because it proves what I've been saying all along, which is that this was a test of the technology. What better test of achieving multiplicity is there than doing another one? I had always figured that there would be another one.

The armature used to create the first of the two Molded Plywood Sculptures by the Eameses, 1941 (image: courtesy of the Eames office).

Disegno Was that disputed by others?

Eames There were clearly pictures of this other one. It was shown at MoMA in the 1940s [Design in Use, 1944], and if you look at the pictures of that from a certain angle, the three points that touch the ground are more spread out. So it was clear that there was another one out there. The one that Charles and Ray kept had been in a number of shows, so even though it wasn't in dispute, there's something very different about actually seeing it. So when the Barbican show [The World of Charles and Ray Eames, 2015] went to Vitra in 2017, that was the first time that the two sculptures were together since they had (presumably) both been somewhere in the office in around 1943. But the point is that the sculpture has always been special and we’ve always had this question around how we should share it with other people. It was a similar thought process to the Elephant, in the sense that we really wanted to come out the first time in its purest form – the original wood. We thought it would be a great thing to do for the 80th anniversary of the office.

A sketch of the molded plywood sculpture, including coding for the various layers of plywood veneer, 1942 (image: courtesy of the Eames office).

Disegno It feels a very good representation of the synthesis of the arts that Charles and Ray were interested in, and which still speaks to a lot of designers today.

Eames Absolutely. The other thing that Charles and Ray were very good at was understanding that aesthetics could be a part of function. So, an example that Charles used was to talk about the old telephone that Henry Dreyfus designed [the Model 302 for Bell Labs, 1937]. It looks alright; and it sounds nice; and it smells okay; and it actually tastes alright, because everybody tastes their phone at one point or another. And Charles said, “Now, if you changed all that so it didn't look great; sounded like nails on a chalkboard; smelled bad; tasted bad, would you say it was more functional or less functional?” Presumably you'd say it's less functional even though all those things are subjective and aesthetic. They grasped that. And while they resisted the temptation to go all the way down that path, they never walked away from it either. One of the things that helped them with that was that they built most of the tools for their early furniture. When you're designing a tool, you need to know exactly what it's going to do – nobody ever designed a tool by drawing a couple of doodles on a notebook. So Charles and Ray wanted to use that same intentionality within tools for the design of the furniture and things like that.

Installation of the Design for Use exhibition at MoMA (image: courtesy of the Eames office).

Disegno So how does this come to bear on the sculpture work?

Eames One nuance that hasn't been clear to a lot of people is that the work they did with the splints [Molded Leg Splints,1943] was an awesome stepping stone towards moulding plywood for furniture. So there's actually another sculpture that they made in 1942, and what's interesting is that if you look carefully at that piece, it has a uniform thickness across the wood. That tells you that they didn’t yet have the control over the medium in 1942 that they they did in 1943. So what happened? Well, by the time they make the sculpture in 1943, they had made thousands of splints. They then made these sculptures on a Kazam! Machine too, probably in their apartment, but the Kazam!s weren’t static, [the Eameses] were improving those machines all the time. The later machine gave them much more ability to vary the thickness of the formed wood, particularly because the veneers were now pressed against metal, rather than wood.

A series of sketches of sculpture-related forms by Ray Eames (image: courtesy of the Eames office).

Disegno How did they see that 1943 sculpture? Were they pleased with it and how did they think it would feed into their furniture?

Eames It was very important to them. It's clear that they were proud of it because they showed in different places. They recognised its importance, but they then moved right onto furniture. I think one of the things they learned is that the sculpture’s level of subtlety in terms of thickness would not be needed by the furniture that they had in mind. So it took them to an extreme point which the LCW didn’t need to go to. But that’s why it was an important test, akin to the Elephant [The Eames Elephant was created in 1945 and, like the sculpture, initially only existed as a series of prototypes. An edition of the Elephant was finally produced in 2007, before entering serial production in wood in 2018, ed.], even if that's a little bit later. One of the key reasons that the Elephant never came out is it's actually harder to make than the LCW. Its two pieces require much more complicated moulds. The Elephant was a great further test of the technology, because unlike with an abstract sculpture, where you have a little bit of liberty, any five-year-old can tell you if you’ve done an elephant wrong.

The new edition of the Eames Molded Plywood Sculpture (image: courtesy of the Eames office).

Disegno The way people read the sculpture is obviously affected by knowing the history and what came next, but it’s a very protean form. It’s somehow suggestive of furniture, as if it’s in the process of becoming furniture, but not quite reaching it. It seems to gesture towards functionality, and then pull back from it

Eames I can totally see that. From my perspective, I see it as kind of a tool for beauty. They clearly knew what the forms would look like and how they would work. They also knew that they would look better made that way, than being made with, say, steel or clay. It's this journey of discovery for the two of them really trying to understand what this can be. I also think that’s why they didn't make a tonne of them. They used this sculpture to get mastery over plywood and they they stepped back a little and didn't immediately use all the techniques they’d developed as part of it. In fact, according to the craftspeople we've worked with, some of their techniques didn't show up till 50 years later in furniture. But having gotten that understanding from the sculpture, they can then design the LCW, they can design the whole Plywood Group. They figured all of this out working with the Kazam! machine and the sculpture is really a very full expression of that whole process. I don't think they bragged about the sculpture particularly, but they knew that it was critical to the journey that that they were on.

The layered paper template utilized in the creation of the 1942 molded plywood sculpture, depicting the number of plywood veneer layers (image: courtesy of the Eames office).

Disegno How difficult is the sculpture to produce?

Eames It's pretty tricky, because you're making the the wood do something that it doesn't exactly want to do. You have to persuade it. What that means as a practical matter is that there's a certain three dimensionality it has to have. A lot of the magic in it is being sure that that you’re getting the legs in the right place. And that took a few goes.

The first Kazam! Machine created by Charles and Ray Eames to produce moulded plywood chair formations (image: courtesy of the Eames office).

Disegno Is the new edition produced in the same manner as the original piece?

Eames Yes. Computer modelling played a critical role in setting the target, in terms of knowing were we had to get to, so in that sense we had a big leg up on the original. But in terms of the actual production, it's really wood veneer and glue being pushed against a metal form, which matches the intention of the designers. It's pretty hands on to the degree that, let's put this way, it would be very inefficient to make a chair in this way. But that just proves the whole point – that this was an experiment for them to figure some things out and see what the limits of the material were. Think of it this way: why was what the Wright Brothers did so important? Because they proved you weren't crazy for wanting to fly. Within a few short years, there were massive improvements in airplane design, but before the Wright Brothers people thought the very idea was crazy. So we had that same benefit with the sculpture of knowing that somebody had already done it. We also knew that, in some ways, if we went too far down a path of trying to be super clever and technological, we were actually less likely to get there.