As Big As A....

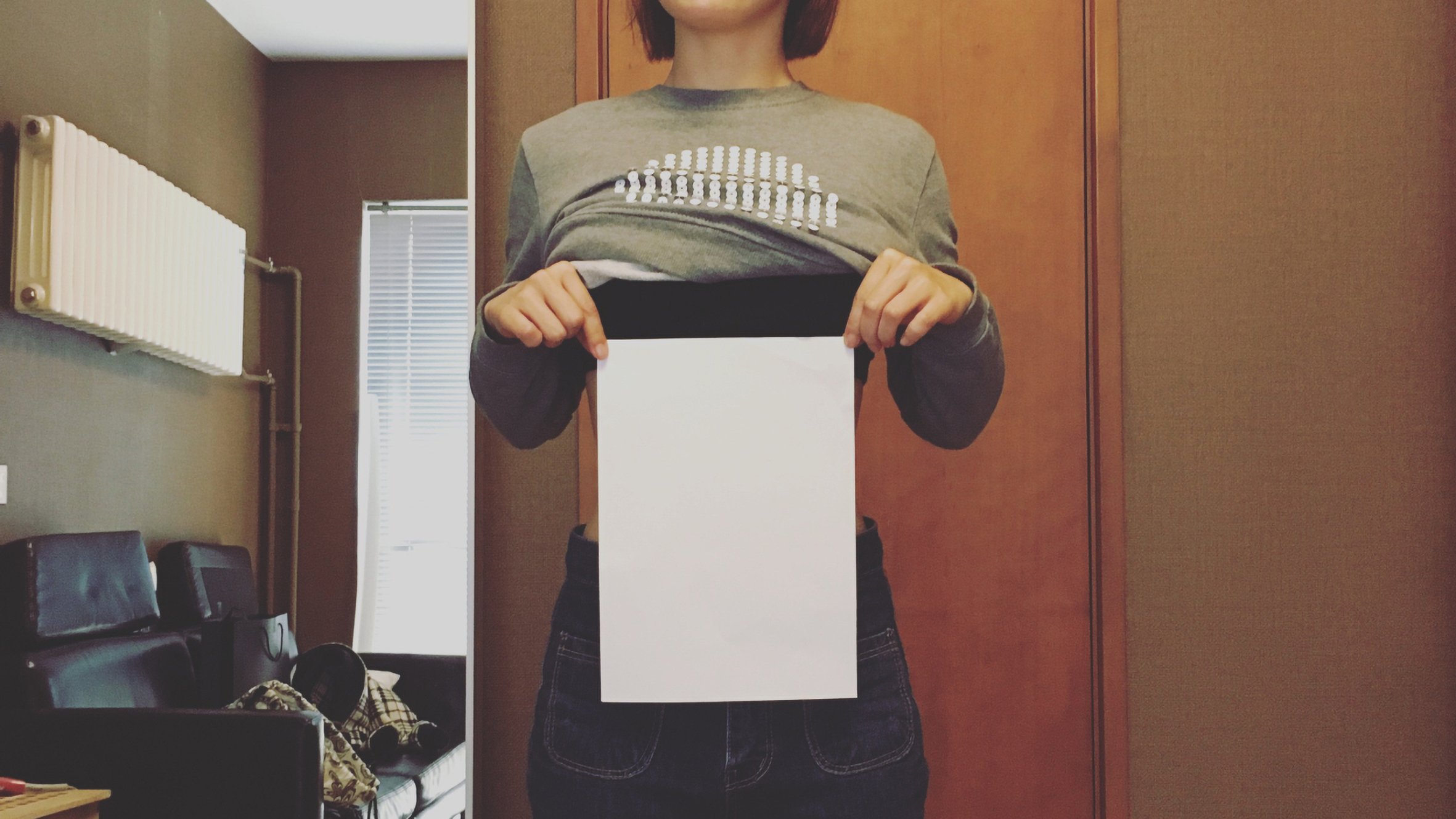

A4 paper and Yuan Shanshan’s waist, 2016 (image: via Weibo).

In 2016, a young woman holds a piece of A4 paper up to her belly. She has an “A4 waist”, which is trending on Chinese social media site Weibo. Two years later, one of my students tells me that the phenomenon has been copied by hundreds of women. As we discuss unhealthy beauty standards, we think, “An A4 waist is skinny, but precisely how skinny? Is it size zero, XXS or 24 inches?”

As many designers will know, A4 is precisely 210mm- wide by 297mm-high, and is the most commonly used paper size in the world (except in North America and parts of Central and South America). It even carries its own international standard (ISO 216). However, it belongs in the world of printed matter, documents and letters – not of bodies or clothing sizes, where sizing is more commonly a numerical measure of circumference. By contrast, the A4 waist is not about digits – it’s about image. In particular, it’s about the front-on flat silhouette, an angle that leaves plenty of room for cheating perspective. But the A4 waist inventively misuses the standard as a visual measure, because it can be found everywhere and understood at a glance online.

Pen and emu egg , 2015 (image: via Vaikoovery, Wikimedia Commons).

A couple of months later, browsing eBay, I eye up a lovely little turned wood vase. In the image it’s paired with a can of Coke. The description says that the Coke can is for “scale purposes ONLY, and not included in the sale”. There is something quite sweet and comical about this odd couple, with the Coke can boldly standing in to vouch for the height of its tiny companion. It’s there to avoid misunderstanding, and to ground the image amid the confusion of online space. After all, digital images are sort of elastic. If I can stretch, zoom and shrink an image with my fingertips, it feels like anything has the potential to be any size.

I begin to wonder: what other objects are being used in this way, and who is correlating these images? As I search the internet for more examples, I realise how much I like looking for things, and how a pre- internet adolescence spent scouring charity shops has led me here – to an endless digital pool of things to be screenshotted, liked, watched and hearted online. It’s addictive. And it’s not just Coke cans and A4 paper that I find. People are using coins, golf balls, pencils, hair grips, bottle caps, matchsticks and lighters – everyday objects that don’t change their standard size over time. I find communities reporting the depths of potholes using Coke cans to measure them. I find an office worker measuring the height of her pile of paperwork with a pencil. I find someone scaling their AK-47 with a ping-pong ball on a Reddit gun discussion thread.

Coke can and mooring rope, 2022 (image: via Raflees Reclamation, eBay).

Hitting what seems to be the jackpot, I discover a category on Wikimedia Commons called “Images with objects to indicate scale”. It’s not the catchiest of names, but it contains many examples of what I’m looking for, classified alphabetically from AA batteries to shoes. The images range from the mundane to the fantastic, including an evocative picture of a cigarette being used to scale a rare Japanese berry branch, by user Namazu-tron, which I save to my archive. Describing my growing collection to a friend at work, we come up with a name – sizegiver.

Over the next year, I notice just how much of everyday life is now navigated through images. From online grocery shopping, lockdown home-schooling, social platforms, and doing everyday work and business, we consume thousands of images daily. As photographers, however amateur, we constantly create and post images to social networks and forums, so it’s hardly surprising that people are making new kinds of images, trying to give a sense of reality and truth to an image by adding a tangible everyday object – a sizegiver. In his 2003 book Arranging Things: A Rhetoric of Object Placement, Leonard Koren explains that an arrangement of objects is a visual language that communicates meaning. “Communication systems,” he says, “like natural languages, grow and develop through perpetual use and experimentation. In the process, the communication possibilities are extended.”

Coke can and porcelain tiger, 2019 (image via @vintiquesmidcentury, Instagram).

Twenty years later, this context of perpetual use and experimentation has deepened. Visual communication feels like our primary mode of interaction. From my collection, I see that sizegiving is becoming an informal practice without particular rules, existing simply to explain something practical – sizegivers often replace the metric/imperial systems of measurement (rulers and tape measures) for speed of understanding. But there is also artistry and creativity in some of the photographs that I find. For example, eBay sellers develop inventive ways to capture the best image of their wares from atop their garage or kitchen table. I notice different stylistic choices through their use of angles, choice of sizegiver, and scale of object – sometimes bizarre, sometimes striking and poetic. A tennis ball in the middle of a plate (for scale, not for dinner); a Rubik’s Cube beside a white leather handbag; a riding crop lying on a domestic carpet, set alongside a US $1 bill. The practice of object arrangement and visual description is unique to each person.

I talk with some of these people on online message boards to understand more about how and why they do this. Gardener Leo Smit uses a golf ball on a stick to measure the rare peonies he grows in his nursery in Nova Scotia. Aptly, peonies begin as golf ball-sized buds, and bloom over a period of days into a dense explosion of petals. He’s been blogging about this process, as well as rare varieties of peonies, since the mid 90s. He tells me that the golf ball is not only for size, but also for white balance and exposure – if the dimples on the golf ball disappear, you can tell the photo is overexposed. We discuss the qualities of a golf ball, its shine, weight and texture, the fact that it is bright and visible against dark backdrops of foliage and earth. Later, I begin to see examples of it being used as an underwater sizegiver to scale coral and aquatic plants. The ball sinks, of course, and it reflects light in murky water. Leo sends me a link to a newly discovered shipwreck, photographed for the local news; its rusty anchor is pictured on the seabed with a golf ball for scale.

Golf ball and peony, year unknown (image via Leo Smit).

I begin to understand there are established methods of sizegiving within particular communities. Pick hammers are generally used as sizegivers by geologists, being a tool that they carry with them. Ed Fox (@foxult), an Instagram user, geologist and teacher in Utah, uses a Sharpie pen instead. His close-up images of rocks, cracks and minerals suit the scale of the Sharpie, which is a handy pocket sizegiver (he tells me he also uses it to correct grammar and spelling on handwritten signs that he sees out and about). This type of pocket object appears in other nature contexts too – a lighter is a common sizegiver for rare or giant mushrooms. It feels like a sizegiver is a key part of a good story; its mundanity proves just how amazing the natural phenomenon you discovered actually is.

I find sellers on Etsy and eBay selecting sizegivers for their aesthetic, as well as practical, qualities. Raflees Reclamation in Somerset sells vintage nauticalia and furniture, mainly as props for the film industry. Its co-owner Lee tells me that they use a Coke can as it’s “obviously world-recognised and gives an instant product size perspective”. Many of their items are vintage, so he thinks a modern, red Coke can gives the correct visual look. I notice that Coke red also calibrates the colour balance of the image, acting a bit like an element in a photographer’s colour chart. I ask Griet, who runs Etsy shop Galerie68, why she chooses a Duracell Plus 9V battery to model her collection of beautifully photographed 1960s Italian homewares. She uses the battery for its universal dimensions, but also because it “does not take up too much space in a photo and therefore does not distract attention from the object”. Batteries exist to collaborate with other objects, but they don’t fit into the objects that Griet sells. This creates a strange and beautiful relationship between the two. The graphic quality of the battery, juxtaposed with the ceramic, plastic and paint-lacquered surfaces of the objects in her shop, again calls to mind the beginnings of a narrative.

Coin and hair donation, 2015 (image: via @eleniswong, Instagram).

Everyday objects have material qualities that we don’t always consider beyond their function. A cork or bottle cap exist to keep liquid in containers, but could have second lives as sizegivers. In Arranging Things, Koren meditates on the sensorial qualities of an object within an arrangement. I start to consider everyday objects beyond their intended function and instead as part-time models and performers of their own physical characteristics. Just as museums, archaeologists or forensics experts use professional scale and colour charts to calibrate a photograph, could a combination of objects convey something similar, or beyond? What could be the potential of everyday things to vouch for texture, softness, temperature, sound, time or weight in an image? I remember the similes that I learned at school, where everyday things are used as points of comparison to enrich an image conjured up by a text: bold as brass, bright as a button, tough as nails. Maybe the sizegiver is a simile in visual form.

In design terms, the most successful sizegivers are the most common, the most famous, the most iconically everyday things that surround us. You could say that they indicate the material culture of our time. For some products, their “design classic” status has meant they have not changed – a Bic 4-colour pen (designed by Marcel Bich in 1969) is universally recognised. For others (not typically noticed as design objects), it is their standardised nature, or the process of manufacture that lets them be reliable sizegivers, such as a 26mm metal crown bottle cap (British Standard En 17177). The more virtual the world becomes, the more I can trust objects: real, simple, everyday objects. They tell me what is real and true.

Coin and dolls’ heads, 2018 (image: via @thehauntedlamp, Instagram).

Or perhaps those truths exist temporarily? I’m looking through a Bruno Munari book, From Afar It Was An Island (1971), which plays with the scale of stones found on an Italian beach, and I discover an image and description of small pebbles scaled by a five-lire coin:

So many stones all different:

one very shiny black one, one dull white one,

one yellow as a pumpkin, one red as a tiny cherry,

one is chocolate-coloured, one black with a white stripe,

one green with spots in a different green,

one grey and black, one gleams as if it contained

fragments of glass; so many little stones no larger

than a five lire coin.

Pencil and sperm whale tooth, 2019 (image: via Akrasia25, Wikimedia Commons).

The coin has a beautiful image of a whale on it, but is now obsolete – replaced by the Euro in 2002. I have no idea what size it is until I buy one on eBay and it arrives in the post. It is the same size as a British 1p, slightly smaller than a European or American 5¢, and unusually lightweight. I try to remember the last time I paid for anything with coins, but can’t. As we move to a cashless society, perhaps we are living through an intermediate period where the only function of a penny is to be a sizegiver, even if it can only function as long as people have living memories of it.

Would a CD still be recognised by gen Z? Many of the sizegivers I’ve found seem to be threatened by obsolescence in one way or another: pencils and paper replaced by laptops; batteries replaced by charging leads; cigarettes, matchsticks, matchboxes and lighters replaced by vapes. Technology is changing fast. Smartphones, cameras and other devices can’t be sizegivers because they update and re-edition faster than they can become familiar. Which everyday objects will become relics of the past, and which will be sizegivers in the future, I wonder? Which timeless, common things will connect my generation with the everyday reality of the next? What objects will live in our pockets in 30 years time?

Words Corinne Quin

This article was originally published in Disegno #36. To buy the issue, or subscribe to the journal, please visit the online shop.