Time and Time Again

“You know,” remarks designer Jamie Wolfond, relaxing in a chair at the back of Milan’s Riviera cultural space, “a lot of people have asked me, ‘Did you find these clocks?’”

From all around Wolfond’s chair, 24 clocks are variously ticking, whirring and spinning, as well as a couple that are doing some more unconventional verbs too. One timepiece is printing receipts, for instance, another is colouring in, while a third is busy live-streaming cows. It would, I think, be a lot of different clocks for Wolfond to have found. “But that wouldn't have been interesting to me,” Wolfond continues. “This is definitely not about putting objects together. I think, maybe, it's more like an experiment in variables and controls.”

24 Hours, curated by Wolfond and Simple Flair for the 2025 Milan Design Week, is a fine example of a typology exhibition – a format in which multiple studios and designers present different interpretations of the same object. In the case of 24 Hours, the brief received by the participating studios, who have been drawn from around the world, was the creation of “a wall-mounted clock that could fit within a 50 x 50 x 50 cm box”. The dramatic differences in the resultant works, however – from the industrial, beautiful and functional, to the absurd, witty and poignant – reveal the naivety of attempting to reduce the work of designers to any cohesive discipline or approach. “I think the interpretable nature of clocks made for a really good lens through which to see completely opposing practices,” Wolfond explains.

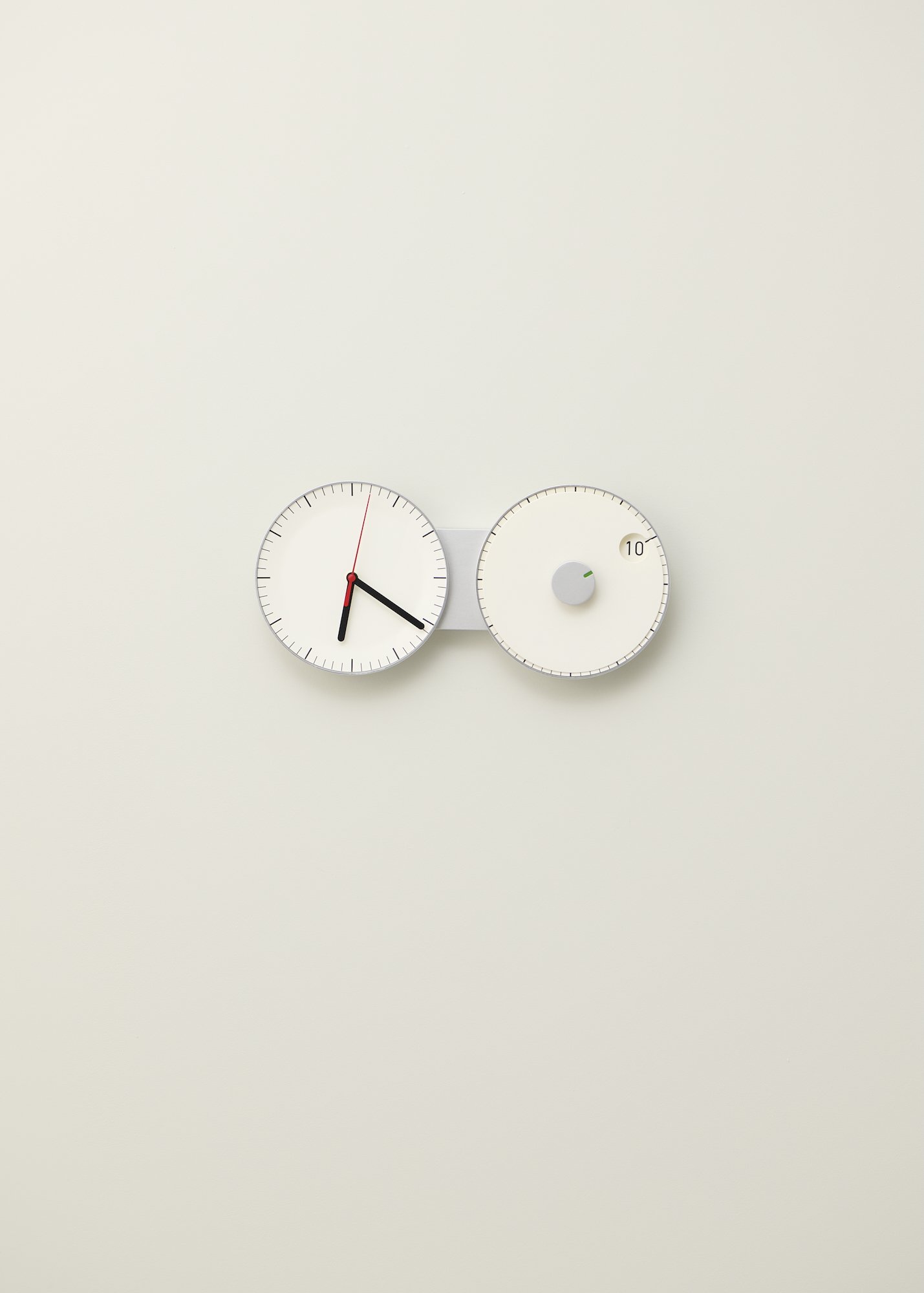

There are works on display, for instance, that speak to industrial design as a rationalising force that seeks to extract maximal value from minimal material. John Tree’s Punch is a pink powder-coated clock, formed from a single sheet of folded steel that allows for two faces punched through the metal. The clock can be mounted on walls or ceilings, while the punched holes interact with the powder coating to create a two-tone effect that improves legibility. A similar effect is achieved through Rachel Griffin of Earnest Studio’s Trim – which is also a pink, tone-on-tone design – but rather than solicit the same precision and economy as Tree’s design, Griffin has instead reduced her design to employ only a single hand, allowing for a less exact, but more meditative and hazy experience of the flow of time. A small tweak gives an entirely different clock, with an entirely different purpose.

Elsewhere, more openly exuberant approaches are on display. Chris Fusaro’s Ravioli with Butter and Sage is a gloriously kitsch sight gag that converts a bowl of bronze pasta into a timepiece (whose dressing of two ceramic sage leaves serve as hands); dach&zephir’s Dendrochro rotates wood veneer at three speeds (hours, minutes and seconds) to reflect the use of tree rings as a means of measuring time; Sam Newman’s 24-hour Clock (Manual) recasts timekeeping as a fantastically bureaucratic nightmare, with a towering 1,440 notebook printed with 86,400 tick boxes for each second in a day; and Shigeki Fujishiro’s Time by Crayon marks out moments by slowly revolving a red ball of crayon around a white frame, the ball smearing itself into oblivion as the trail it leaves behind darkens and thickens over time with the buildup of rubbed material.

The latitude afforded by clocks to enable such varying interpretations, Wolfond explains, was the central driver for the show. “If I had not come up with clocks, I wouldn’t have wanted to do this,” he tells me. “But what is completely different about clocks from any other category is that although they’re a measuring tool, like a ruler or a compass, they also have this completely secondary function as a symbol for a way that people express their craft values, or use craft to express their values in general. Every object does that to a certain extent, but there is this duality within a clock of doing something very basic and necessary, while at the same time being very expressive.” I think of Maddalena Casedei’s Rittorno – an instrument-like stainless steel wall clock, whose aura of solid functionality is accentuated to the point of anachronism through the addition of a spiral cord. In 24 Hours’s accompanying publication, Casadei explains that she wished to play up the analogue quality of her clock to near absurdity, positioning it in direct contrast to the surfeit of digital technologies (and their attendant notifications) that we are now surrounded with: “That dangling cord becomes a quiet invitation to slow down, to notice the small, overlooked details of life.”

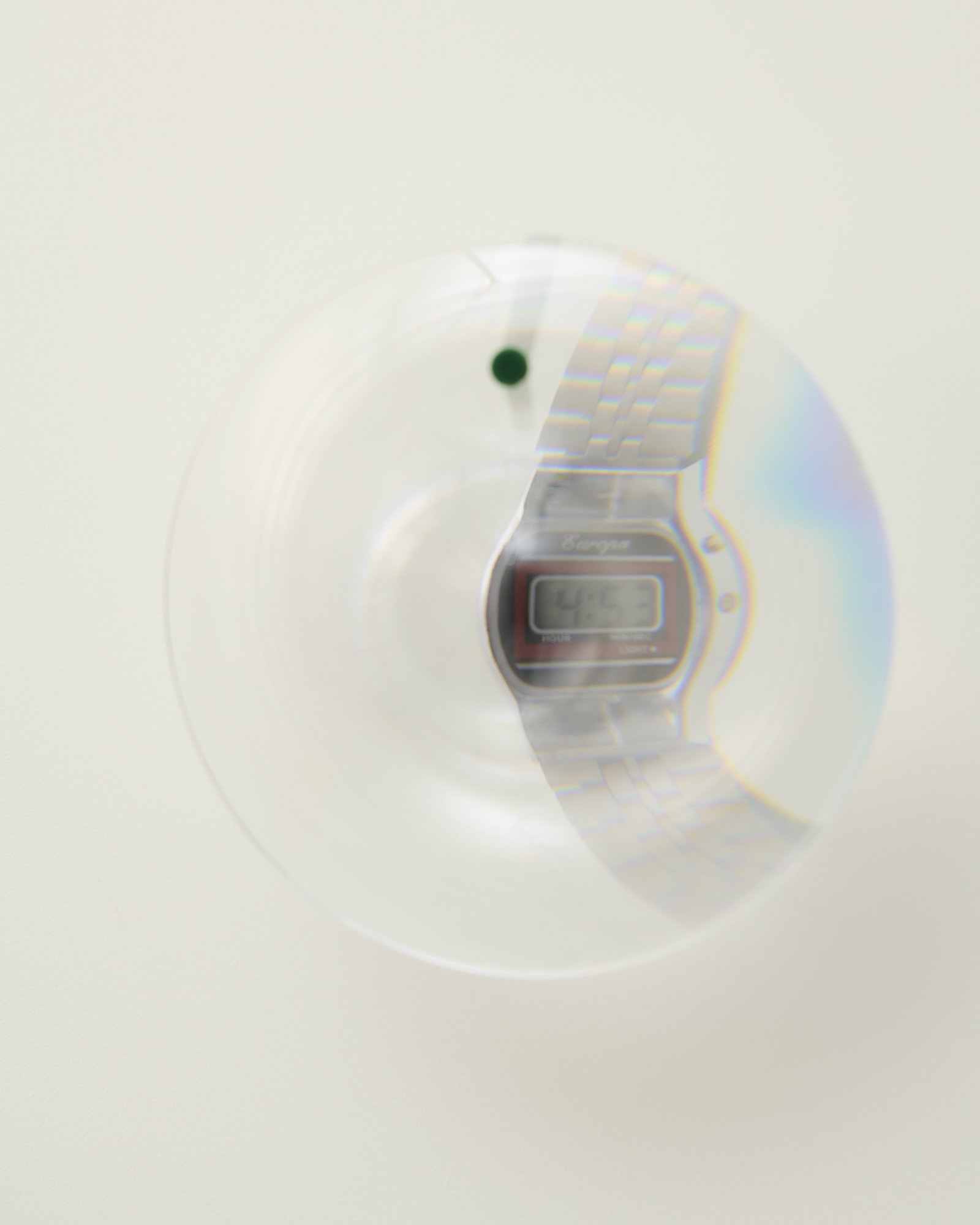

Across the exhibition, designers have made hay by exploring the contemporary status of dedicated clocks and watches in everyday life, and the assimilation of their functionality into smartphones and other digital technologies. Chris Kabel’s Wrist to Wall, for instance, meditates on the relative obsoletion of wristwatches, mounting one of the devices on a flocked armature behind a fresnel lens – a setup that magnifies the watch’s face to the size of a wall clock, cunningly converting (and revitalising) the dead tech at the heart of its design “from something private to something public.” Sina Sohrab’s Real Time, meanwhile, ingeniously displays its time through a four-screen device that offers live streams from CCTV cameras around the world, all of which are spectacularly engrossing through their sheer banality, offering fascinatingly tedious windows onto cow sheds, car dealerships, barbershops and more. Sohrab’s device poignantly “measures its abstract passage through an unfiltered sprawl of everyday life,” but is rich enough to also provoke reflection on topics such as the attention economy and the expansion of digital platforms to fill an ever expanding proportion of people’s time.

Wolfond has chosen his subject well. The reduction in status of clocks as measuring tools has, in turn, correspondingly emphasised their expressive role, with 24 Hours revealing the different considerations, values and approaches that drive its participating designers (or, more accurately, drove them in this project). Tree’s emphasis on economy and industrial elegance plays off against Fusaro’s sculptural wit; Casadei’s concern for an individual user’s wellbeing finds a complementary balance in Sohrab’s wider social lens. No approach is more valid than any other, and the show delights in the diversity it encompasses. “Think of chairs,” Wolfond tells me. “Why do we make new chairs? I don't think people's bodies are changing, so the need to make a chair a certain shape is not evolving either. Technology is evolving, but those are small, incremental changes, so I don’t think that’s a reason to design new things either. I think we design new things because our cultural environment is changing, and we use objects to help us digest those changes. That could also explain why we still have clocks.”

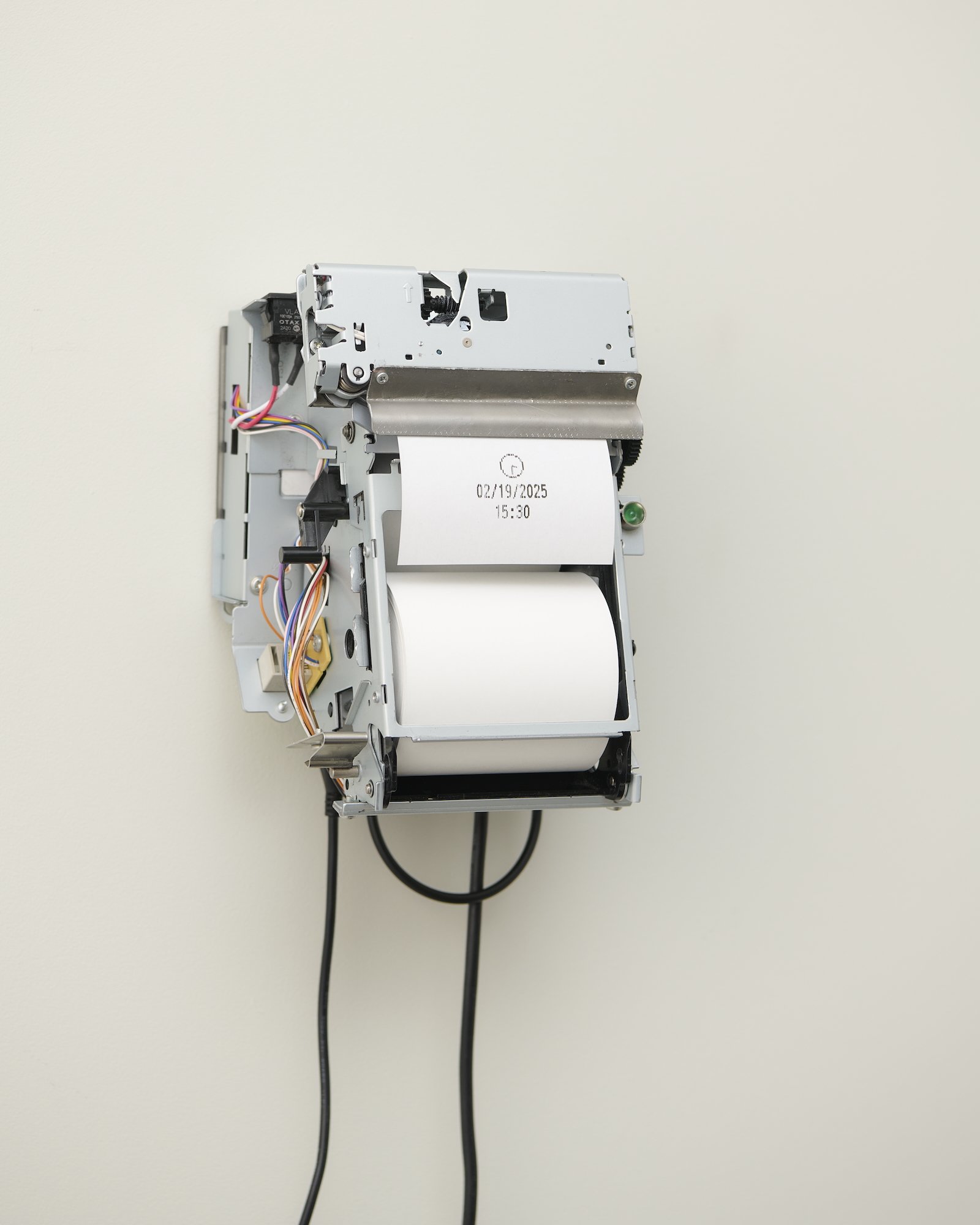

In this vein, Wolfond’s own contribution to the show becomes relevant. Final Sale is a hacked receipt printer, programmed by artist Matt Nish-Lapidus to print the date and time every single minute. A blinking light marks the passage of seconds, while Wolfond has adapted the printer so that it fully slices off each printed minute, allowing the time to flutter to the floor, accumulating in vast piles over the course of its installation – a performance of hilarious pomp and ceremony, wickedly undercut by the steady accumulation of its dead minutes in ever increasing mounds. It is a perfectly functioning clock – its printouts as horologically precise as anything else in the show – but it is also strange, funny, mournful and gloriously bathetic. It is, in itself, a fine embodiment of the multitudes that are embodied not only in clocks, but also in design as a whole.

“There was no expectation that people would make a clock that necessarily functions,” Wolfond tells me, “and at first I was getting a few messages from designers saying, ‘I don’t know if you’re going to think my clock is really a clock.’ My response to that was, Well, my clock prints garbage.” He sits back in his seat, surrounded by the ticks, whirs, rips and rolls of the 24 clocks. “Usually that calmed people down.”

Words Oli Stratford

Photographs Benjamin Lund