Politically Erect

World’s Best Condom Factory in Denmark (illustration: Alastair Philip Wiper).

Between the Monkeypox outbreak[1] and the overturning of Roe v. Wade – coupled with the ongoing documentation of all aspects of our lives through TikTok in desperate attempts to go viral – Alastair Philip Wiper’s short films and photographs shot inside the Worlds Best Condom Factory in Denmark begin to feel like a fertile allegory for our present moment.

Founded in 1956, Worlds Best today occupies the corner of a cheese factory owned by DKI Group, a relatively anonymous operation that, according to its website, “consists of 10 companies with activities within a wide range of business areas.” Cheese and condoms appear to be two of these.

As you may have guessed from its present location, Worlds Best’s glory days are long gone, a period from the 1970s to 1990s that were, in part, brought on by an increased demand for condoms as a result of the AIDS epidemic. The brand’s standalone factory shuttered in 2018 and the company moved into the aforementioned factory, which specialises in grated varieties for pizza toppings. I can’t help but wonder if the two tribes of workers take their lunch breaks together, comparing notes on quality control.

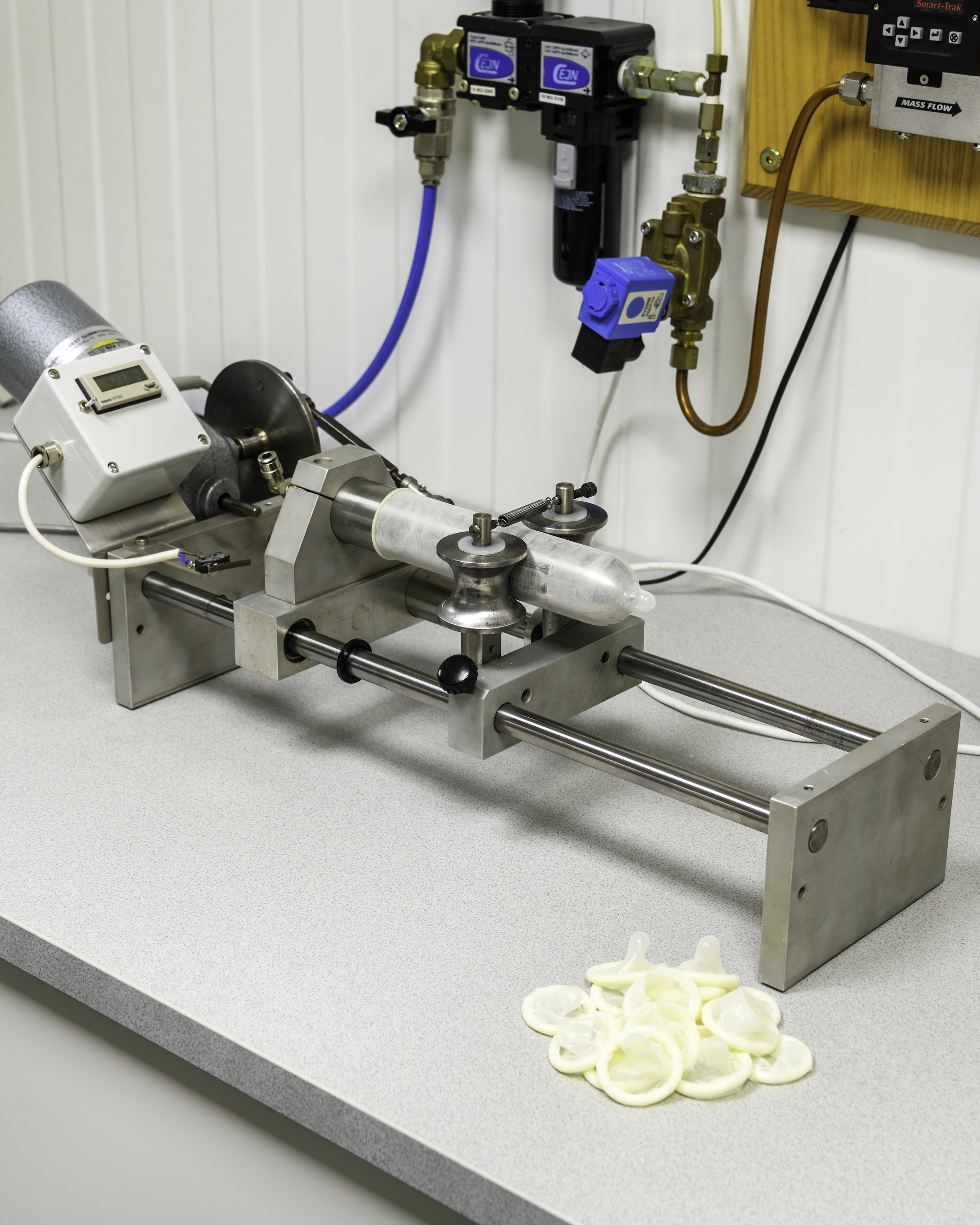

In the tradition of “How It’s Made”, Wiper’s photographs and videos from this factory grant us access to a rather whimsical production process. The machinery looks as though it has changed little since the 70s and human presence is constant. The effect is something that I imagine Wes Anderson would appreciate, and provides a stark contrast to the outside world, increasingly ruled by algorithms and automation. Videos of the testing process – a condom being inflated to the size of a human torso, a row of water-filled condoms swinging to and fro, a condom-covered metal shaft repeatedly thrusting between two gears – are hypnotising and absurd. Watching these objects subjected to such physical extremes through primitive measures is intensely satisfying. Ironically, I suspect these videos would perform well on TikTok.

Since somewhere around the dawn of civilisation, humans have desired to fornicate without risking inconvenient results. In Ancient Rome, condoms were made from linen and animal intestines, and there are unsubstantiated reports that tissue from defeated (human) combatants was used as well. Casanova was anti-condom when he was younger, but came around to their value after contracting STIs. He apparently became accustomed to inflating them before use to make sure there were no holes (if only he’d had Worlds Best).

Since then, condoms have come a long way. Until the 19th century, they were essentially luxury items, primarily used by the wealthy, but a confluence of social activism and industrial innovation (in the form of rubber vulcanisation) served to ultimately bring condoms to the mass market – despite the best efforts of legislation such as the US’s Comstock Laws that attempted to limit their dispersal. In spite of their spread, however, condoms’ fortunes have often been tied to tragedy. STI rates tend to surge in accordance with wars, with access to and promotion of condoms following to varying degrees across different countries throughout the 20th century, while the discovery of AIDS in the early 1980s caused unprecedented promotion of condoms, despite many conservatives’ beliefs that abstinence was the only answer, and that rates of infection amongst homosexuals were a deserved moral consequence for victims’ “sins”.

This brief history of condoms illustrates a cycle we find ourselves facing once again. As issues of sexual health return to the top of news agendas, as bodily autonomy comes under threat, and as misinformation spreads like wildfire, our current moment starts to resemble a game of 4D chess against a sociopathic algorithm. Wiper’s images, in their depiction of a methodical and consistent world, bring this sinister complexity to light through harsh contrast. As I watch a condom being inflated to the point of resembling a birthday balloon, or a half-dozen sheaths filled with water, jiggling back and forth like cartoon characters, or countless little condoms on their little condom conveyor belt, I can’t help but see them as jolly and confused volunteers. They’re bouncing their way to the front lines, striving to protect the fragile human race, wielding their durability and elasticity to the best of their ability.

Worlds Best Condoms are ready for whatever comes at (or in) them, having survived their rigorous and comical testing process. The real question is how we can create government policy, public-health programmes, and scientific innovation that can surpass the efficacy of our latex friends from Denmark. As a wise man once said, “Condoms aren’t completely safe. A friend of mine was wearing one and got hit by a bus.”

[1] Monkeypox is not an STI, it is a disease spread by close contact and fomites, but it does represent a sexual health equity issue for the LGBTQ+ community.

Words Ria Roberts

Photographs Alastair Philip Wiper

This article was originally published in Disegno #34. To buy the issue, or subscribe to the journal, please visit the online shop.