Design for the People

The few photographs of Vilhelm Lauritzen that exist show a shy and serious man. The Danish mid-century architect was a more humble figure than his better-known contemporaries, Arne Jacobsen and Finn Juhl, who are often pictured puffing on cigars or pipes, and reclining proudly in their iconic chairs. Since Lauritzen’s death in 1984, these vintage portraits of a man who wanted little attention have been closely guarded by his family and can only be viewed at his Copenhagen firm Vilhelm Lauritzen Arkitekter (VLA) – a now mid-sized practice that continues the work that the architect began in 1922.

One photograph of Lauritzen in his later years shows him patiently at work on a butterfly collection, carefully pinning specimens’ wings into pristine glass cases. From behind the camera and drawing board, he was an observer of the natural world, borrowing its motifs and sense of order to put a spin on modern architecture and design that was unique for the time. Modernism renounced vernacular materials and frivolous decoration, but from within the movement Lauritzen found a more sensitive expression that fits the canon, but occasionally subverts its functionalist dogma. “There is no life without aesthetics,” is his famous quote, allowing himself the artistic freedom to insert clever touches and personal details into a portfolio of landmark projects that included a department store, an embassy, airport terminals, theatres and concert halls.

Lauritzen worked in a golden era when an architect would handle all aspects of a building, down to its fittings and furniture. As such, VLA has been left with a rich archive of designs specific to individual projects. Most familiar is the VL Radiohus lighting range produced by Danish brand Louis Poulsen, which stems from Lauritzen’s bespoke fittings for the Radiohuset – the headquarters of national broadcaster DR, completed in 1945. The VL45 pendant is a simple elongated globe of white opal glass that hangs like a raindrop about to fall from a strand of spider’s web.

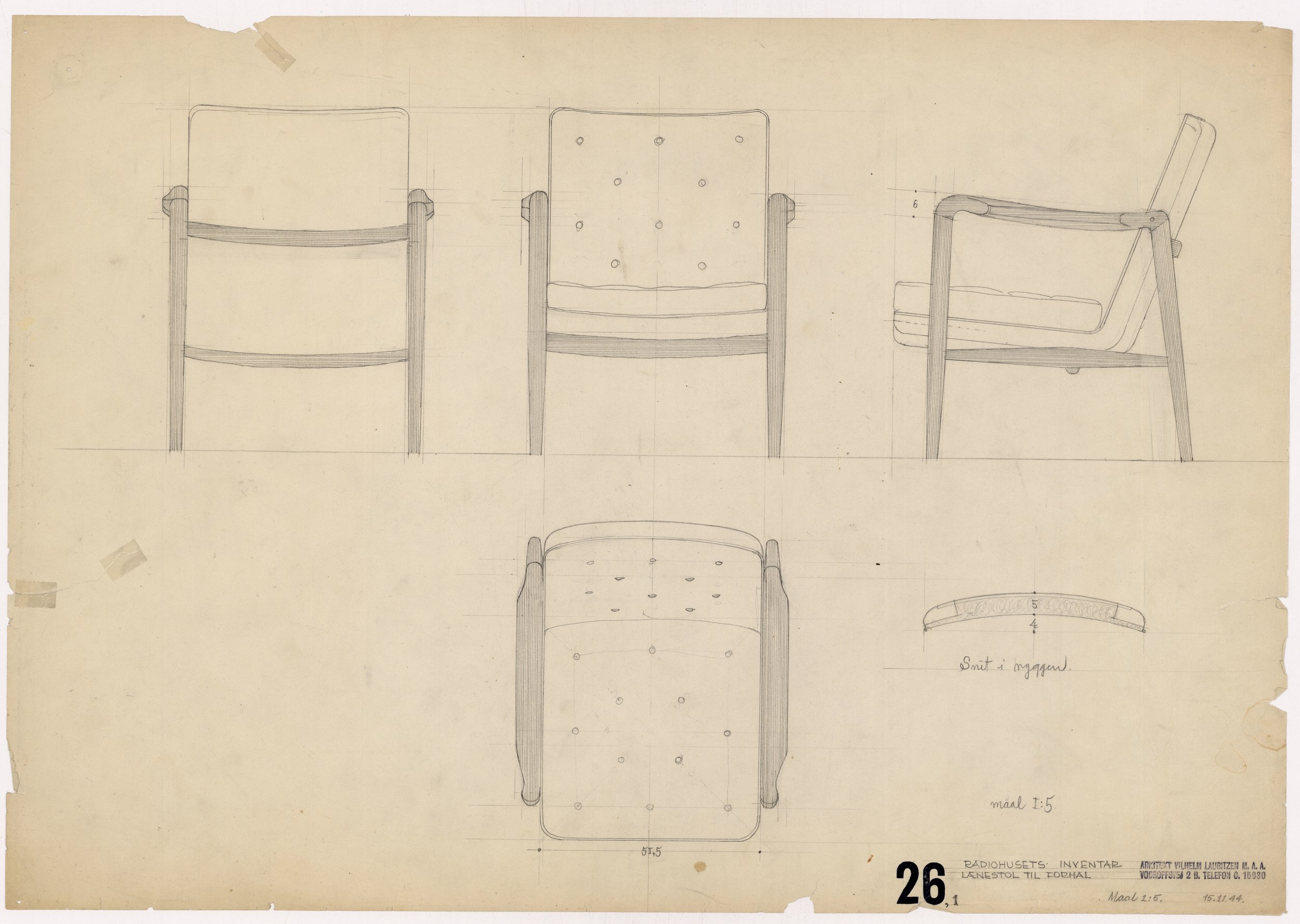

VLA's centennial this year gave it an opportunity to revisit the archive and look at other products and furniture. “We were blown away,” says VLA partner Anne Møller Sørensen. “There are over 1,100 original designs by Vilhelm Lauritzen. We thought it would be great to bring some back to life and make it possible for people to enjoy them at home, the office or elsewhere.” Working with the Danish furniture brand Carl Hansen & Son, VLA selected the original bench, chair and couch designed for the waiting areas at Radiohuset to revive under the title of the Foyer Collection. Lauritzen’s VLA26 Vega chair will also be reissued – a stackable design that is original to one of Copenhagen’s most-loved live music venues, Vega, which was oiginally designed as a community centre by the architect in 1956.

The original bench featured in the Foyer Collection is still in use at Radiohuset, now home to the Royal Danish Academy of Music. The building is a dense complex on a tight urban plot that manages to combine subterranean recording studios, a hangar-like canteen, wisteria-framed roof gardens and a premium 1,000-seater auditorium made for visitors to appreciate music live as it is broadcast. The bench is made in two- and three-seat sections shaped to meet the auditorium’s curved outer wall. It’s a clever, space-saving design for this compact venue, using the teak-lined wall as back support and giving waiting concertgoers a radial view of the spectacular first-floor lobby. The multi-height space is a mix of modernist hallmarks and surprising decorative details. Thick white cylindrical columns support a ceiling that tapers smoothly to the floor above, and a zebra-striped floor laid with teak and birch meets expansive windows to the north and south. There are sweeping metal balustrade details that border on filigree and, in the ship’s hull of the timber-lined auditorium, chains of delicate white opal lights are entwined along the brass rails separating tiers of seating.

These stylistic contrasts speak of a shift for the architect and the age. Lauritzen’s early designs were in the classicist tradition, but his travels around central Europe in the early 1920s would come to influence him as a modernist. He saw the auditorium at Radiohuset as a chance to set the standard for a modern concert hall; its design predates London’s Royal Festival Hall and the Sydney Opera House by five or more years. The building’s interiors are materially rich with a consistent palette of Greenland marble, timber, brass and leather, combined in different ways to provide subtle changes in atmosphere and acoustic effect. Radiohuset was designed both for the audience fortunate enough to hear concerts in-person – its door handles are mounted on steel plates so as to avoid ladies’ cocktail rings scratching the wooden doors – and for the one at home.

“He was very interested in the time he was living in,” says Sørensen. “The radio was an expanding media at the time, a new way of communicating, of bringing the world [into] your living room. For Lauritzen, broadcasting meant bringing time and space closer together.” Constructed during the Second World War, the building has a sense of robustness and resourcefulness too. The striped birch and teak floors were a response to limited quantities of each timber at the time. It was originally due to complete in 1941, but construction was purposefully delayed until the end of the war to avoid Nazi occupation of the building during the German invasion. Lauritzen cleverly built in bespoke features such as clocks and mirrors so they couldn’t be dismounted and taken away.

Getting into both the era and the architect’s mindset were key to developing the Foyer Collection. Mads Holm Rabjerg, head of product development at Carl Hansen, worked from a combination of drawings, old photos, and a few original pieces that still exist. “We were very lucky to find a sofa in the basement, but it had been reupholstered a few different times,” he says. “Looking at it closely we saw holes in the wood, so we knew it originally would have had buttoned upholstery.” This detail has been faithfully restored in the new collection, as have the two precise folds of leather that cover the narrow arms of the chair and sofa. But the aim of the collaboration was not to make replicas; both parties felt the furniture had to be relevant to today’s consumer. The furniture’s shapes and sizes have been rethought to be more versatile. The rounded back of the sectional bench was made straight. The three-seat version was abandoned in favour of the two-, to suit smaller living spaces.

“When we sat in the original, and also our first prototype, we could see these were made for a different era,” says Rabjerg. “For this collection to be relevant again we had to change the angles a little bit for comfort.” The back and arms now have a more relaxed profile, and the oak-framed range is comfortable to sit in despite its formal look. Pieces come upholstered in leather, as they would have been at Radiohuset, or wool, which Rabjerg says gives the pieces a “much younger visual expression”. Taking Foyer out of context also meant redesigning small elements that would not have been noticed in a large space such as Radiouset. “The legs of the bench especially looked a bit too thick, so we took the dimensions down a notch to be more elegant and fitting to the rest of the series,” says Rabjerg.

If the Foyer collection was made for the genteel classical concertgoer, the Vega chair was for the working man’s knees-up. The 1956 design is original to Lauritzen’s Folkets Hus, or people’s house, a place where workers and their families in the Copenhagen neighbourhood of Vesterbro could come together and celebrate life events. Since 1996 it has been known as Vega, a popular venue on the live music circuit. Past performers here include Bjork, Prince and David Bowie.

“It’s a very different project to the Radiohuset,” says Sørensen. “It’s much more festive.” Embodying a sense of postwar optimism, the interiors are freer in their use of colour. Dark wood veneer lines the floors, wall and ceiling of most of the interiors. Lauritzen used the medium to vary the acoustic performance depending on the space’s function, whether speaking, listening to music or general socialising. The architect packed multiple event spaces into an efficient building of just 42,000sqm. At the edges are long bars and banquet rooms with natural light and views over the busy thoroughfare of Vesterbrogade. Hidden in the centre are two halls for audiences of 500 and 1,150 people. Vega’s complex construction of mezzanines, various entrance and exit points, and double staircases were designed for people to flow in and out quickly – several events can happen simultaneously without the audiences ever meeting.

“If you look at the plans and sections you’ll see it’s super compact; everything has a function and it’s kind of playful the way it’s put together,” says Sørensen. “I’ve been here several times and I always get lost trying to get out!” The venue sees 200,000 people pass through annually, hosting up to 360 shows, from children’s theatre to club nights. It is designed to be intensively used and, despite signs of wear and tear – and a few glitzy additions such as a light-up bar from the 1990s – the building is in remarkably good condition. Many of Lauritzen’s original features remain intact. Decorative details are less precious than at Radiohuset, but still show the architect at play. In both halls there are marquetry artworks of intersecting geometric shapes. The same scattered approach to lighting is here, with small, bud-like opal lights set in chandeliers over the staircases, uplighters that provide diffuse and direct light, and large hanging globes that illuminate punters’ faces at the bar.

Vega is a more basic building than Radiohuset, and while neither is conventionally beautiful, the former’s charms are better hidden. There was an attempt to pull it down in the 1990s; its sticky floors and smoke-filled social rooms were due to be replaced with a steel-and-glass supermarket complex. Luckily, a couple of local politicians saw its importance, however, and it lives on. Musicians love to play here for the atmosphere, which is a tribute to Lauritzen’s architecture. Timber-lined interiors, low ceilings, and warm lighting all give it an intimate feeling, and Vega’s convivial energy comes from the multiple crowds that can throng through it thanks to Lauritzen’s efficient use with space. The building is a puzzle box, with rooms that can be subdivided in various ways to make them just the right size for the type of event. Panelled doors between rooms fit into niches either side when opened, to give the feeling of one continuous space. When closed, the use of matched veneers makes them seem to disappear into a single plane.

Lauritzen furnished his building with 800 foldable stacking chairs that, like the building, were designed to take a few knocks. The design has now been re-imagined by VLA and Carl Hansen as the Vega Chair. Sørensen describes the original being “as common as possible” and “a design for the people”. Updating this practical, steel-framed chair with a bentwood back and seat meant optimising its stability and improving its comfort. It no longer folds, but can stack eight-high compared to the original four. To make it a more versatile piece across home and contract use, it comes in a version with an upholstered seating pad. “Most importantly, we needed it to meet today’s standards in terms of durability,” Rabjerg says. “So we designed it to come apart. If a part gets knocked, stained or scratched, it can just be replaced.” The new version also has small bumper pads underneath the seat to avoid the chairs damaging each other when stacked. Although some of the chair’s fixings have been concealed to give it a more streamlined look, the oak seat and back sit a little proud of the powder-coated steel frame, hinting at its potential for disassembly.

Research on reviving the chair began two years ago, with an auction-house search for early prototypes, close examination of those that remain in use at Vega, and a contradictory set of Lauritzen’s archive drawings. “Every time you design you make compromises, and it was the same then,” Rabjerg explains. “There are some great details in the drawings that didn’t end up in the original chair. In some cases we were able to bring them back.” One “quite charming” element that the design team felt compelled to keep are the wooden feet that cap each of the chair’s splayed insect-like legs. Like dancers’ shoes, these feet make it seem the chair could skip off at any moment across Vega’s dancefloors. The chair comes in a range of colours in tune with the building’s retro spirit: black, white, pale pink and blue, as well as a natural oak version.

The new Vega chair is a fine balance between Lauritzen’s intentions and today’s expectations – not a replica, but a composite of past design and present manufacturing capability. A further challenge was to keep this “people’s chair” at an affordable price: the new version will sell for around €500. Despite addressing all these demands, it doesn’t feel like a compromise. There is practicality, charm, robustness and even a little flair. Lauritzen was determined that his work should be his legacy, not his personality. In reviving both these designs, VLA and Carl Hansen haven’t attempted to make him a household name. Instead, a new generation has been allowed to appreciate the fame-shy architect’s unique take on modern values, life and design.

Words Riya Patel

Photos courtesy of Carl Hansen & Son