The Biodegradable Aphrodite

Biodegradable packaging samples (image: Theresa Marx).

Apparently, you’re not meant to keep a lipstick for more than eight months. “And I never knew that,” says the designer Insiya Jafferjee, eyes widening behind her spectacles. “Personally, I’ve never been a big beauty user, but beauty enthusiasts will throw a lipstick away after eight months. I mean, I had my lipstick for years.”

Well, eight months really doesn’t sound very long at all, which makes me suspect this whole thing could be a bit of a scam. You know, beauty’s equivalent of the Phoebus cartel, rigging the system to keep sales of Rouge Dior, Ruby Woo, and Black Honey Almost firmly in the pink. “I’ve heard it’s not meant to be good for your lips if you use it for longer than eight months,” explains Jafferjee. “Certain things dry out.” Now, I’m not sure whether those things are ingredients in the lipstick or else elements of your lips should you apply old product. Could out-of-date lipstick trigger an instant shrivelling? “So there is quite a bit of waste in that industry when you use the products correctly,” Jafferjee summarises. She is presumably unaware that I’m now solely concerned about my lips withering when touched by eight-month-old Pillow Talk.

Nevertheless, the waste she mentioned should probably be a concern too. Jafferjee tells me that, pre-pandemic, the global cosmetics industry produced an estimated 120bn units of packaging per year, the bulk of which is plastic. “Which, in terms of packaging, places it second behind the food industry,” adds her colleague Amir Afshar, who has just brewed a very good pot of coffee indeed, making expert use of a French press. He explains that coffee-making in the studio can be a competitive business and that they all have their own preferred methods. And while he admits to being a bit underwhelmed with his latest effort, I personally like a French press, enjoying both how manual and French it is, the former of which actually has some relevance to the issue at hand.

“At its base level, food packaging is a box with a lid,” explains Afshar, “but cosmetics packaging is much more complex, because you have mechanisms and systems.” Lipsticks roll up; creams pump out; coffee is pressed. This, I think, is a good point, and in a bid to join in with the conversation1 I explain that it had never occurred to me that lipstick even has packaging. The holder just sort of is the lipstick, I suggest, with the stick and container integrated in a fashion you simply don’t get in food, bar notable exceptions such as the Push Pop and the Calippo. “Beauty has ways to dispense things that are between packaging and engineering,” agrees Afshar. “When you look at a pump, it’s made of around five different types of plastic, and there’s likely glass and metal in there too.” In the world of beauty, packaging is product.

The long and short of this, Afshar and Jafferjee explain, is that a significant proportion of cosmetics packaging is sufficiently complex such that it cannot be readily handled by existing recycling streams. This, in turn, ought to pose questions over the effectiveness of prioritising recycling in combatting plastic waste. “We would love everything to end up in exactly the right waste stream and if that was the case, recycling would be great,” says Afshar, “but the reality is that those systems are broken.” That isn’t particularly pessimistic either. According to a 2017 paper in the peer-reviewed Science Advances, only 9 per cent of the 6,300 metric tonnes of plastic waste estimated to have been produced up until 2015 has been recycled. Seventy-nine per cent of this plastic waste has simply accumulated in landfill or the natural environment, with the remaining 12 per cent having been incinerated. It means that the bulk of your used cosmetics are probably still out there, polluting the waterways, shredding into microplastics and getting stuck up turtle’s noses like wrathful ghosts of your past beauty.

“Recycled plastic is fabulous,” summarises Afshar, “but at the end of its life, the recycling system is still broken. All you’ve added is an additional step.” And he’s right. The authors of the Science Advances report conclude that if current production and waste management trends continue, around 12,000 metric tonnes of plastic waste will be in landfill or the natural environment by 2050. “That means that when we design materials,” Afshar explains, “we need to design them such that if they don’t get captured by those waste streams, they remain benign and don’t do anything detrimental to the environment.”

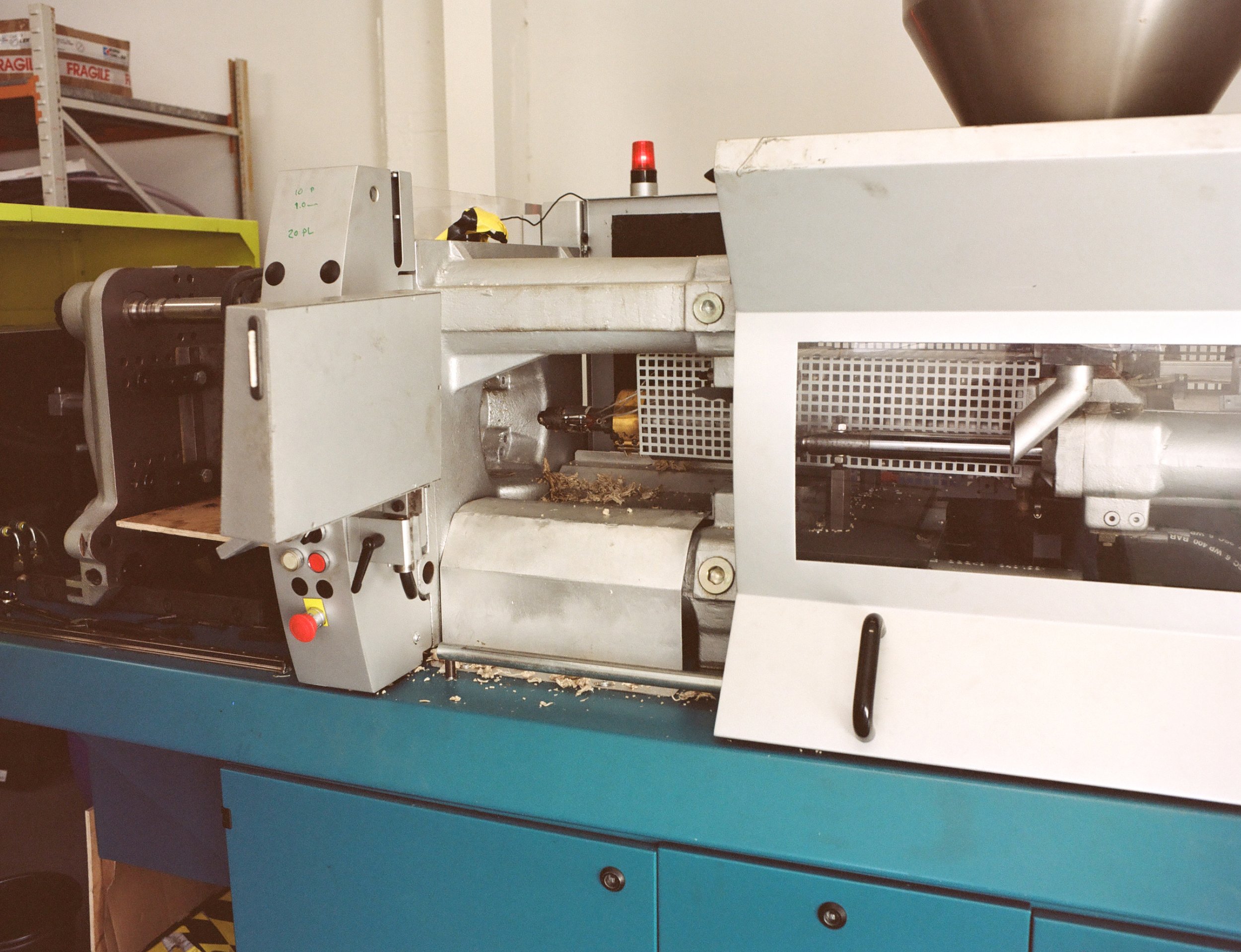

Pellets of Shellworks’ Vivomer material, ready to be injection moulded.

Someone should probably do something about all of this, which is why Jafferjee and Afshar have set up their design practice to try and intervene. The pair are two of the co-founders of Shellworks, an eastLondon startup that has created a range of packaging made from a biodegradable polyester typically used within medicine to create resorbable medical devices, such as sutures, meshes and implants. This polyester eschews petroleum as its base material, and is instead synthesised by bacteria. “It’s made from a fermentation process that is quite similar to how vinegar or beer is made,” says Jafferjee, explaining that as bacteria feed on a carbon source, they create polyesters in their cells. “You can think of it as fat,” adds Afshar, cutting through the science with an instinctive understanding of the communicative value of well-fed, contented bacteria. “It’s an energy storage system, which we then extract before the bacteria, and this is a loose term, start exercising and using that energy.” That liposucked polyester, once combined with natural additives such as cellulose-based fibres, forms a bioplastic that can be processed in the same manner as any conventional thermoplastic. “It’s [environmentally] benign,” adds Afshar, “but also injection-mouldable and mass manufacturable.”

As well as avoiding fossil fuels in its production, the Shellworks bioplastic has a number of material traits that support its use within the cosmetics industry. “It’s got good barrier properties against oils and waters, which for packaging is obviously great,” says Afshar. “It’s very rigid, although we’re now working on a more flexible variation too, and it’s also fairly robust. But the major selling point is that it naturally degrades without the need for any special conditions such as high humidity or temperature – bacteria that exist abundantly within marine and soil environments break it down through an enzymatic process.” This is significant, not least because it’s not true of many biodegradable plastics, which tend to be prima donnas about when and where they’ll begin their personal disintegration. Polylactic acid (PLA), for instance, is technically biodegradable, but requires industrial composting conditions, including temperatures above 58°C, if this reaction is to take place. “You put it on the package [that it] is biodegradable,” notes Frederik Wurm, a chemist at the Max Planck Institute for Polymer Research, in conversation with the University of Minnesota’s Ensia, “but at the point where these materials are[…] fear[ed] to end up, they will not biodegrade.” If PLA ends up on a roadside or floating down a river, it won’t reach the temperatures required to compost. It will simply endure, stoically.

“Recycled plastic is fabulous, but at the end of its life, the recycling system is still broken. All you’ve added is an additional step.””

In this respect, Shellworks’ material represents a significant improvement. While it will still be subject to the vagaries of environmental conditions and temperature to some extent, it won’t just sit there, mournfully waiting for an industrial composter to come by and end it all. Which all sounds very encouraging, because if we’re going to be buying new lipsticks every six months for fear of oral desiccation, it seems only right that the empties should themselves shrivel up, ashamed. Enthused, I ask about the new material’s name. “We call it Vivomer,” says Afshar. “We wanted something that could take the notions people have of polymers, but also suggest something living.”

But what is it known as in the medical industry?

“The base material is polyhydroxyalkanoate,” Jafferjee replies.

That’s less catchy, I say.

***

Shellworks, delightfully, is based on Fish Island, a former industrial area of east London close to the Olympic Park. For those who enjoy nominative coincidences, it is also a few doors down from a Shell garage. “We didn’t think about it at first, and then our packages began getting delivered to the garage,” says Jafferjee, with couriers sending photographic proof of delivery for parcels that were nowhere to be seen. The only clue as to their location, Afshar explains, was “a very blurry photo in which you could see some shelves,” with those shelves no doubt well stocked with de-icer and Boost bars. “Then you think, Hmm, maybe they’re at the Shell garage.”

That name, Shellworks, reveals something of the company’s origins. The studio began life as a student group project for the Royal College of Art and Imperial College London’s Innovation Design Engineering (IDE) MA/MSC. “We specifically wanted to do something with an ecological impact,” explains Jafferjee, who had worked with Afshar before. “Amir had been working with new materials for a couple of years already, so waste materials kept coming up in the conversation.” The pair partnered with course-mates Ed Jones and Andrew Edwards, and the four began exploring the possibilities of chitosan – a biopolymer extracted from the exoskeletons of shellfish. Although used in medicine for its antibacterial properties, chitosan, the team discovered, is not widely used in design or industry, despite being the planet’s second most abundant biopolymer after cellulose. “Very early on we identified that our strengths were design, engineering and manufacturing,” Jafferjee explains, “which was interesting because the reason why chitosan hadn’t taken off as a polymer was the manufacturability of it.” Developing a series of processes and machines, the team were able to create chitosan objects and packaging that could be used as natural fertilisers at the end of their lifespans. As well as being ecologically responsible, these pieces were oddly beautiful: duskily translucent vessels, amber and veined, like a rich bisque left out to achieve glorious solidity. After graduating in 2019, Jafferjee, Afshar and Jones decided to take the project on as a start-up.

Shellworks was an early success. Prior to moving to Fish Island in August 2020, the company received studio space as part of the Makerversity programme at Somerset House, and over the course of its lifespan it has raised $1.2m in investment and an additional $600k in grant funding. Alongside this institutional support, the team also began fielding enquiries from the beauty industry. “Within the beauty or personal care space, people already care about ingredients because they’re having to interact with the body,” explains Afshar. “Perhaps they also think more about sustainability because they’re already considering where things come from and how they interact. It’s an interesting space because [historically] there doesn’t seem to have been a lot of solutions, but at the same time there is a very vocal community asking brands for something different.”

Packaging samples and material experiments created by the team.

In response, Afshar explains, a number of “clean beauty brands” have emerged that trade on their environmental credentials. The Ordinary sells its skincare within apothecary-style glass dropper bottles with pipettes; Kankan packs body products in aluminium drinks cans like artisanal colas; and Lush sells “naked” lipstick refills sealed in biodegradable wax à la Babybel, with the brand reporting to have sold 16,108,320 unpackaged products in 2019, accounting for 62 per cent of its total sales. “There’s a definite shift and some brands now have an ethos of saying, ‘I don’t mind paying a little bit more for my packaging as long as it’s sustainable,’” Afshar summarises. “We’ve had a lot of conversations with brands of all different scales, because even the bigger players are cognisant that change is coming. If they don’t invest or make decisions towards it now, it’s going to be problematic down the line.”

The chitosan products, which Shellworks branded as Shellmer, seemed as if they might play a role in this change, with an order arriving in 2020 for 5,000 pieces of packaging. “It was as we were trying to scale up to complete that first order that we understood how difficult the manufacturing was going to be,” explains Jafferjee. The issue, the pair explain, is that chitosan is a stubborn polymer that resists industrial processes, which is probably what you might expect of something extracted from the mighty mantle of a crab. “Getting it to scale in conventional manufacturing processes was pretty difficult,” says Afshar. “It doesn’t operate like a traditional plastic. While it has really good properties in that it can degrade quickly, those also mean that it’s difficult to put anything in, because as soon as you do so it starts to break down.” Although these issues can be somewhat mitigated by the addition of other materials, chitosan’s material quirks make it difficult to fit within existing manufacturing systems. “We were going to have to create our own factories,” says Jafferjee, “which would have taken immense amounts of money.”

“For chemicals in general, there are very few people trying to innovate at a large scale. It’s conservative as a industry.”

At the same time as these manufacturing issues became apparent, retailers began asking questions about provenance. “They have a checklist you have to go through,” Jafferjee says, “and one is that your product has to be vegan.” Shellmer, of course, is not – given that what cellulose is to trees, chitosan is to prawns – which itself raises questions about the ethics surrounding material alternatives to plastics. It would clearly be preferable for plastic substitutes to not require the death of animals, but Shellmer is also a material created from a pre-existent waste stream that isn’t going away any time soon. According to the UK’s Marine Management Organisation, British fleets alone caught 146,800 tonnes of shellfish in 2019. Those are a lot of waste shells, the bulk of which enter landfill, yet an early video explaining Shellworks’ chitosan material on YouTube saw debate erupt in the comments section:

“Those shrimp and lobsters need their shells,” commented JE Hoyes

“The global production of farmed shrimp in 2017 was estimated between 2.9–3.5 million tonnes,” responded Pyrotixs. “All those shrimp were grown in farms and were purposely bred to be eaten and discarded. The purpose of this research is to utilize the discarded shells. Its better for it to be recycled than to end up in a landfill.”

“Pyrotixs It’s better for shrimp to be left alone and not caged in intensive farms on coastlines,” replied JE Hoyes, undeterred. “Shrimp farms cause environmental damage.”

“Get with the times hippie, it’s not 1960s anymore,” interjected Richard Russell. “You should be more worried about Yellowstone.”

I don’t tell Afshar and Jafferjee this, but JE Hoyes is my kind of hippie. I am staunchly against catching shellfish for food, or any animal for that matter, and believe there are good ethical reasons for this. I also, however, have sympathy with the environmental rationale behind making use of waste materials, as argued for by Pyrotixs:2 it’s an imperfect world, and it may be better to play the hand that society has dealt us, rather than foregoing incremental improvement in favour of a sea change that is unlikely to come. At the same time, it’s difficult to stomach ongoing harm to animals, even if their polymer-rich remains could be useful in the service of a supposed greater good; it’s hard to see how systematic change can be brought about unless you hold the line somewhere. Shellmer’s veganism debate, then, is an interesting real-world dilemma, but not one that can be accommodated for by marketing. The need to dive into murky ethical waters, Jafferjee explains, is incommensurate with brands looking for sustainable packaging as an easy selling point for consumers. “Dealing with the question over veganism becomes an additional thing for brands to take on, whereas we wanted to make it as easy as possible,” she says. “It becomes a very personal issue,” Afshar adds, “and so it’s better that we don’t add yet another level of complexity to that.”

Faced with these technical and ethical issues, the company pivoted towards polyhydroxyalkanoate, a material that had come up during its early research into medical materials. “We spend a decent amount of time looking at the medical industry because, ultimately, if something can go in the body, then it has probably been rigorously tested so as not to be detrimental to the environment,” says Afshar. “It just so happens that a lot of those materials are really expensive, because they’re either produced at a very high purity or else in small quantities for a specific process. There are always opportunities to say, ‘How can we use this in a different way? How can we reduce the cost, and increase the amount available?’”

As such, while the team grappled with the dual limitations of chitosan, ultimately turning down that initial order for 5,000 pieces (“Quite a big decision,” summarises Jafferjee), they were also reassessing polyhydroxyalkanoate. “I was working on fundraising and looking at all of these different technologies we’d considered in the past,” Jafferjee explains, “and I asked Amir, ‘Why is this one bad again?’ And we couldn’t find an answer, because in fact it’s a really good solution.”

The new material, the team explain, is simply better suited to the industrial demands placed upon packaging than chitosan. “With the previous material, even if we had a rigorous process, 10 parts would come out perfectly and then the 11th or 12th would be a disaster,” says Afshar. “And there’d be no reason for that, beyond it was perhaps a little bit more humid on a Tuesday afternoon.” For the past eight months, however, the team have been able to produce consistent injection-moulded Vivomer parts. I ask whether they’ve managed to recoup that lost order for 5,000 units using the new material. “We started with a 1,000-piece order, we’ve just done 5,000, and now we’re working on 25,000,” Jafferjee responds. “After that, we’re talking about doing 100,000 units for customers on a monthly basis.”

So many fat bacteria.

***

The fruits of Shellworks’ labours are littered around their Fish Island space. Metal tooling adorns its tables and shelves, and a Boy 55M injection moulder sits proudly next to buckets of putty-coloured test parts, freshly pumped out. Another machine, a twin-screw compounder, is on order and due to arrive soon, unless it was inadvertently delivered to the Shell garage weeks ago. Meanwhile, a miniature laboratory sits to the rear of the space, complete with a chemistryclass fume cupboard and petri dishes filled with plastic smears and powders. Tubs of various gums, one of which promises high acyl, sit mystifyingly among the detritus. Nearby, a set of egg-yolk yellow lockers is discreetly labeled with a flammable materials hazard symbol. It must, I realise, be where they keep the serious chemicals. Or else fireworks. Probably the chemicals, though.

The team has been in the space for just over a year, but they’re already operating a micro production facility from within its confines. “We design our own tools, get parts, injection-mould them, and then test them,” says Jafferjee. “And we work on the material formulation in tandem.” The team currently develops Vivomer’s chemistry in-house, experimenting with different compositions, but Afshar tells me that they’re also hoping to begin working with the bacteria directly. “Can we go right back to the cell?” he says. “Could we get the bacteria to actually create different types of polymer?”

“Too may people told us what we couldn’t do when we started out and said that the things we wanted were impossible. That hasn’t been our experience.””

“We’ve been working with a supplier on that so far,” adds Jafferjee, “but think we could learn about the material more deeply and make changes at a more granular level ourselves.” We have, I realise, moved a long way beyond establishing the ideal method for coffee preparation Although Shellworks works with industrial partners to produce in volume, the studio tries to operate in as self-sufficient a manner as possible. “For chemicals in general, there are very few people trying to innovate at a large scale,” Jafferjee explains. “It’s conservative as an industry.” The result of this, she says, is stasis. If a factory’s setup is geared towards traditional thermoplastics, it’s difficult for alternatives to get a look in, particularly given that new materials – even those specifically designed to fit within existing industrial processes – demand a degree of calibration. “The industry has been doing the same thing for 50 years or even longer,” Afshar summarises, “and new materials coming into that sphere are typically made by material scientists who don’t really care about the way they’re going to be manufactured. They just give it to someone who does injection-moulding, who will then run it as a conventional plastic before giving up within 10 to 15 minutes because it doesn’t work.”

These issues are largely structural. Although consumer-facing brands are under pressure to move towards more sustainable packaging, it is typically the packaging manufacturers themselves who have direct contact with new materials. “We speak to companies who will say, ‘Well, we’re looking for this particular thing, whereas our existing packaging is just what we could find,’” explains Afshar. The standard model sees brands select packaging from manufacturers’ catalogues before applying branding, or else they hire industrial design consultancies to develop more custom pieces. “There’s a huge industry of those [consultancies],” notes Jafferjee. “So you end up with a lot of intermediaries.” What doesn’t tend to emerge from this ecosystem, however, are new materials, because there’s little financial impetus to fund their industrial development. “People will try to sell new materials to manufacturers, who are then responsible for selling those on to [companies],” says Jafferjee. “And that’s where it breaks down, because the manufacturer doesn’t want to take on a new material if there’s no benefit to them. They have to put in extra work, the cycle time to make the product is longer, and therefore costs go up.”

Amir Afshar and Insiya Jafferjee.

With so many roadblocks to overcome, Shellworks’ bacteria probably have time to exercise around the clock. They’re probably bacterially hench. Which is why the studio’s solution to this tangle of competing interests is to try and reduce complexity by assuming the functions of several different types of companies and, in so doing, better connect the elements of the system that presently short-circuit one another. It is, I think, a little like the plot of Mrs Doubtfire, in which a divorced Robin Williams attempts to gain greater access to his children by dragging up as an elderly Scottish nanny in order to heal family trauma by playing multiple roles at once. Greater synchronicity between elements leads to fewer competing interests (in packaging, not in Doubtfire, where it somewhat backfires to cinematically amusing effect), and so Shellworks is geared towards simultaneously engineering materials, designing packaging, and then organising its industrial production. “It’s not just a packaging company or a design company or a biotech company, but a hybrid of all three,” says Afshar, “because one of the issues facing the industry is that brands speak a very different language to packaging companies, and they definitely speak a different language to scientists and engineers. We see ourselves as a communicator between these different parties.” As, no doubt, did Williams.

“Going straight to the customer is unique in this industry,” explains Jafferjee, “because if you can convince them, they’re then able to convince the manufacturer to take on this extra burden.” Beauty brands, she suggests, are increasingly willing to accept higher prices for packaging as an R&D cost, or else can justify charging more for a product if its sustainability credentials are up to snuff. “Small things like that are where more traditional packaging companies don’t intervene,” Jafferjee says.

Actually, I suspect there are multiple areas of the manufacturing process in which Shellworks intervenes more than most. From listening to Afshar and Jafferjee talk, a significant proportion of their work seems to concern itself with logistics – ensuring that factories feel comfortable working with their material and don’t give up on it before they’ve cracked its industrial production, because the road to thermoplastic relapse is paved with good intentions. “When we send a tool out to someone so they can do a production run, we will also go there, help the person tune it in, and make sure they can comfortably run it,” says Afshar.

“If you can say, ‘Here’s a beautiful piece of

packaging that is high performance, a similar price, and also sustainable,’ why wouldn’t brands switch over?”

And that’s not going to be a 15-minute process. It’s going to be a two-hour process of them learning how to use it,” adds Jafferjee. “Because too many people told us what we couldn’t do when we started out and said that the things we wanted to try were impossible. But when we’ve actually tried those things ourselves, that hasn’t been our experience.”

***

For better or worse, change is coming. In April 2022, the UK introduces its Plastic Packaging Tax, which will impact all plastic packaging manufactured in, or imported into, the UK that does not contain at least 30 per cent recycled plastic. The scheme will, the government argues, “provide a clear economic incentive for businesses to use recycled plastic in the manufacture of plastic packaging, which will create greater demand for this material. In turn this will stimulate increased levels of recycling and collection of plastic waste, diverting it away from landfill or incineration.”

This, I suggest, is broadly a good thing – right? Jafferjee and Afshar are measured in their response. Although Vivomer largely avoids the problems that the changes are being brought in to address, the legislation will tax the material identically to virgin plastics, which perhaps goes to show quite how broad and unhelpful “plastics” can be as a piece of terminology. “Regulation is trying to have a positive impact, but there are certain nuances in the stuff that they’re passing that has upset the renewables industry,” Jafferjee says. There are fears, she explains, that larger companies have bought up supplies of post-consumer recycled materials, thereby positioning them to dominate the market. “And also,” she adds, “we’re trying to make renewable plastics! We don’t want to have any petroleum plastics in it.”

The team’s Boy 55M injection moulder.

“It’s a weird dynamic, because people need to think about the whole picture, rather than just snippets,” agrees Afshar. The problem, the pair suggest, is that although the tax is well meaning, it is too blunt an instrument to tackle the complexity of the problem it attempts to solve. “It’s definitely easier from a messaging point of view to say to a general consumer, ‘Oh, that was 100 per cent virgin plastic, now it’s only 70 per cent and that’s great,’” says Afshar. “But there are questions around how you even assess whether someone’s put 30 per cent recycled plastic into their packaging, because chemically it’s the same.”

Such things matter, because the lattice of policy, economics and industrial systems within which new materials launch largely determines their future success. Afshar tells me that the team identify as “critical optimists”, and the first element of this compound seems the more pressing of the two. As well as being sceptical about the current efficacy of recycling, Afshar and Jafferjee devote similar scrutiny to potential issues with their own material. Polyhydroxyalkanoate may bring advantages over traditional plastics, but it also relies on a carbon source in its production. “You can use something like sugar, or you can use a waste source as well,” says Jafferjee. Of the two, waste seems the more environmentally palatable, tying back into the approach adopted with Shellmer, “but there are pros and cons that come into even that decision,” says Jafferjee. “The primary one is cost, because even though waste may be cheaper initially, you still have to purify it and that purification process may not be the most sustainable.” Although a polyhydroxyalkanoate plastic is positive in terms of end-of-life decay, the production of its bacterial feedstock also has to be taken into account – not least when this plays into issues around land-use if space that could be employed for food production is instead diverted towards plastics. “Where is it grown? How much land does it take up? How much water is needed?” summarised the University of Georgia’s Jenna Jambeck in conversation with National Geographic. “Bio-based plastics have benefits, but only when taking a host of factors into consideration.” Feeding bacteria is more complex than it sounds, particularly as I’d assumed they just ate mud or something.

These debates around production, Jafferjee and Afshar say, play out in their discussions around synthesising polyhydroxyalkanoate in-house, as well as in their reflections on the wider costs of their process. As a base resin, Vivomer is two to four times more expensive than a traditional plastic, but the cost of the packaging can then be brought down through engineering and the nature of the beauty industry. “It’s about where you put your energies in terms of market,” says Afshar. “So food packaging is disgustingly cheap, a fraction of a penny basically, but within the cosmetics industry a large amount of their costs are already in packaging, because that’s where they can communicate something to their customers.” This, he says, allows Vivomer to compete. “Within that industry, we can get pretty close to what they’re paying for conventional plastics,” he says. “It’s more like 10 or 15 per cent more expensive, which is relatively palatable.”

To demonstrate his point, Afshar brings over a box containing a number of sample products that the team has designed, several of which will launch this winter with brands including Liha Beauty, Sana Jardin and Bybi Beauty. Inside the box are monomaterial spatulas, tubs, and containers, and the team have also produced lipstick holders and droppers. A mono-material pump, they say, is currently in development. The present samples are immaculately engineered, with precise screw caps, robust bodies that feel comfortable in the hand, and the Shellworks logo – which looks like a kind of simplified Celtic knot – moulded daintily on their bottoms. Each piece, the pair explain, is not only trying to replace their nonbiodegradable equivalents, but improve upon them. “One thing that we hear all the time from customers is that they don’t have a solution for sampling, so we’re trying to work on that now,” says Afshar. “If companies don’t do sampling, people just end up buying the productand, if they then don’t like it, they throw it away – so that’s wasteful. On the other hand, if they do sampling, they have to send out loads of small packages, which is also wasteful. So we’re trying to find whether we can engineer something that balances the two.”

In addition to careful engineering, the team places considerable focus on the aesthetic of their products. Vivomer is able to stably hold natural dyes, allowing for a range of custom colours across pieces. “That’s more and more becoming our selling point, because matching a brand’s colours gives them confidence in you,” says Jafferjee. “There are some limitations, such that we might tell a customer that there will be a variation between two Pantones, but the fact that we are able to talk in Pantones is massive, because most companies won’t even do that.” She tells me about a conversation with a client that had proceeded positively until, suddenly, the customer raised an issue around colour. “‘Wait, wait, wait. You guys can make green, right?’” she remembers. “And we had actually already tested that brand’s green, so we sent them a sample pack. It was only then that they replied, ‘Let’s continue the conversation.’ It’s nuts, because it’s a simple thing to think about, but it’s something that other companies really struggle with.”

The samples in the box are a creamy oatmeal with ginger fleck, but elsewhere in the studio are teals, purples, blues and greens – some are matt, others speckled, and a handful of more experimental material studies have been executed in swirling ombres. Even within the more basic colours, there is depth. Vivomer is pearlescent, creating layers of colour that run through the material like lacquer. They feel too pretty to rot into mulch, but then I suppose that all beauty is ephemeral. If it wasn’t, the global beauty industry wouldn’t be worth some $500bn, and we’d all have more money to spend on French presses and chocolate bars from the garage. “Having designers in the team really helps, because we can be critical of ourselves,” says Jafferjee. “Sometimes people think that more scientific and material-based companies aren’t going to care about what something looks like, but for us it has to look beautiful and that’s what helps sell it to the customer.” Which sounds about right. Visual flourishes are niceties when considered alongside the severity of the plastic problem Shellworks aims to address, but they do matter in persuading brands to consider alternative materials. “If you approach companies and just say, ‘Here’s a sustainable version of the packaging you’re using,’ they might feel it’s interesting from a personal point of view, but not invest because it’s not a priority,” says Afshar. “But if you can go to them and say, ‘Here’s a beautiful piece of packaging that is high performance, a similar price, and also sustainable,’ why wouldn’t they switch over?”

Vivomer colour samples, produced using natural dyes.

Well, let’s hope he’s right, because if we’re not going to be keeping our lipsticks for more than six months, it seems unfair that the planet should have to suffer them for hundreds of years instead. Given those 120bn units of packaging per year, that’s an awful lot of old lipstick left knocking around. “We talk a lot about this triangle,” says Jafferjee, “which is performance, cost and sustainability. If one is missing, then we’re not going to take off in scale, and the fundamental thing about plastics is that if you want to make an impact, you have to act on a large scale.” And that’s good to hear, I think, because just imagine the global shrivelling that’s en-route if we don’t.”

1 This broadly sums up my interview technique.

2 To my mind, only Richard Russell comes across badly in this exchange. To hell with you, Richard Russell!

Words Oli Stratford

Photographs Theresa Marx

This article was originally published in Disegno #31. To buy the issue, or subscribe to the journal, please visit the online shop.