The Power of the Poster

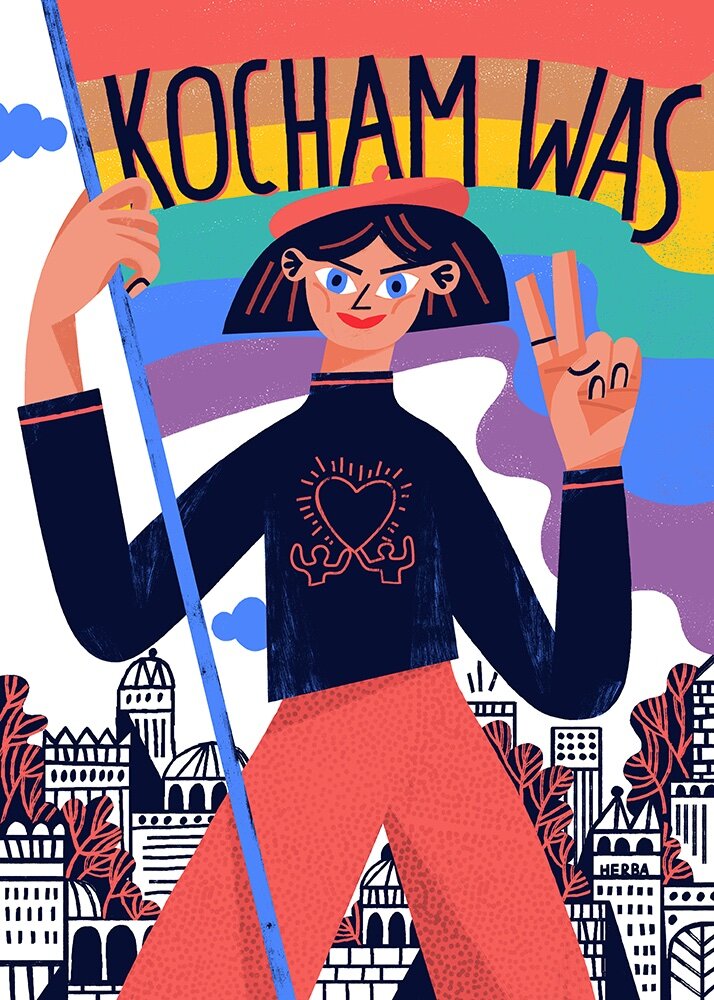

Aga Giecko (@agagiecko), June 2020.

For Disegno’s 10th anniversary, we’re republishing 29 stories, one from each of the journal’s back issues, selected by our founder Joahnna Agerman Ross. From Disegno #27, Zosia Swidlicka talks with the Polish graphic designers who used their art to campaign against homophobia in the run up to the 2020 election.

As a child growing up in 1990s Poland, Aga Giecko would often accompany her parents to the polling station on election days.“I remember how each polling station, usually a local school, gave a strong feeling of its local community,” she recalls. “You’d end up chatting to your friends and neighbours surrounded by official government announcements mixed with kids’ drawings. It made it feel like a day of celebration, like people would drop political disputes for a day and realise we were all part of something bigger.”

This year, in the run-up to the presidential election, the mood in Poland was far less jubilant. Despite the nation experiencing its longest period of true independence since 1795, fears that Poland is being run in an anti-democratic and authoritarian manner have been mounting since the right-wing populist Law and Justice party (PiS) came to power in 2015. Most alarming has been the steady overhaul of the judicial system, which has recently given politicians the power to fire and fine judges for actions they deem harmful. The party says the reforms are needed to fight corruption, but the European Commission has opened a legal case against Poland, fearing that politicians could use the reforms to control rulings. Vying for another five years in power, the government has now run a bitterly divisive re-election campaign grounded in homophobia, with LGTBQ+ activism construed as a threat to the nation.

In a campaign speech delivered in Brzeg on 13 June, the sitting Polish president Andrzej Duda attacked LGBTQ+ rights as a direct threat to Polish national identity. “This is not why my parents’ generation fought for 40 years to expel Communist ideology from schools, preventing it from being foisted on children, brainwashing and indoctrinating them,” he declared to supporters. “They did not fight so that we should now accept that another ideology, even more destructive to man, would come along – an ideology which hides deep intolerance under its clichés of respect and tolerance”. Nor was this bigotry restricted to Poland’s government – the nation’s Church leaders also spoke out. On the 75th anniversary of the Warsaw Uprising, the Archbishop of Kraków, Marek Jędraszewski, thanked God that Poland was no longer affected by the “red plague” of Communism, but added that a new “rainbow plague” was coming to “control our souls, our hearts and minds.”

“The rainbow does not offend! Solidarity is our weapon!”

Amidst the hostility and hatred of the campaign trail, however, a completely different story was starting to unfold on Instagram. Polish illustrators and graphic designers were creating and sharing poster graphics in solidarity with the LGBTQ+ community. Several illustrators, such as Aga Giecko and Zuza Kamińska, worked on their own initiative. Countless others, however, including Gosia Herba, Natalia Łajszczak and Grzegorz Myćka, created works for Pogotowie Graficzne (Graphic Emergency), an initiative which rallies designers to create posters around specific political issues, sharing the results online, as well as making them available for printing so that they can be displayed around town or taken to protests. “We do not agree with the abuse of power against sexual minorities,” the group said in a statement. “We do not agree with the dehumanisation of nonheteronormative people and the open hostility of the state towards them. We do not agree to police brutality. The rainbow does not offend! Solidarity is our weapon!”

Politically-engaged posters are an established tradition in Polish graphic design. The country’s most famous design movement, the Polish School of Posters, operated from the 1950s to 1980s, gaining worldwide renown for expressive, hand-painted film posters that often hid underlying political messages. “The posters were often very euphoric, very colourful, very symbolic or allegorical, and they often had a surreal undertone,” explains cultural historian David Crowley in a 2016 interview with culture.pl, a website set up by Poland’s government-sponsored Adam Mickiewicz Institute. Poster artists working under the Communist regime were subject to strict censorship, which resulted in “a completely unique contribution to visual culture.” These designers found ingenious and increasingly bold ways to toy with state censors and engage viewers in a secret game to see how much they understood. “This marked out the Polish Poster as fundamentally different to what people expected of Eastern Bloc culture, but also fundamentally different from the design practices that were happening in the West,” notes Crowley.

One of the most striking examples of subversive metaphor in the Polish School of Posters is Mieczysław Górowski’s 1982 poster for the play Policja (Police), by one of Poland’s greatest playwrights, Sławomir Mrożek. It depicts a rope winding through the chin, mouth, ears and eyes of a face. It is an effect that the curators of MoMA’s 2009 exhibition Polish Posters 1945-89 noted “is suggestive of both victim and oppressor: like their prisoners, the police hear, see, and say nothing. Martial law was imposed in Poland in December 1981 in an attempt to crush support for Solidarity, the first non-Communist trade union in a Communist country.”

Zuza Kamińska (@nekrofobia), June 2020

Contemporary Polish illustrators seem comfortable employing this same mode of graphic communication, matching their forebears for subversive wit while also creating new visual languages to describe the present day. Operating with fewer restrictions than their predecessors, the current generation of Polish artists and designers are free to confront political issues head-on in their work – at least in theory. There is still a risk of their work being labelled “LGBT propaganda” by government bodies and publicly funded institutions. Speaking to Art Review, artist and activist Karol Radziszewski noted the dangers of this situation. “Sometimes people ask me how much censorship I experience in Poland, but it’s hard to answer because most of the time, I’m not aware of it: people are making these decisions [in] private,” he explained. “A director might say ‘we’re not putting him in the programme, we don’t need the trouble’ and I’d never hear of it.” It’s a situation that won’t necessarily lead to an arrest warrant, but could well affect artists’ reputations and bottom lines in the long run. As Giecko points out, “It saddens me to see politicians encouraging hatred and misinformed people spitting in their neighbour’s face. Anyone could be next.”

To understand where these tensions have come from, we need only to glance at the past five years of PiS rule. Duda’s policies appeal to voters who feel left behind by previous, more liberal governments. To them, Duda is the defender of the traditional Catholic values that they see as synonymous with Poland’s national identity, and they welcome his policies, including the controversial judicial reforms, because they believe Duda is taking money from rich, corrupt judges and putting it back in their pockets. At a PiS rally hosted in Opoczno one week before the Presidential election, for instance, the state-owned broadcaster TVP reported that “women and men admitted to one another that, while each government levied huge taxes, no one had so far shared them so heavily with citizens.” In 2016, for instance, Duda unveiled a generous welfare programme that gives parents a tax-free benefit of 500 PLN (£100) per month per child under the age of 18. It is a policy which risks incentivising women to drop out of the labour market, and which undoubtedly reinforces a traditional conservative worldview, but it has nevertheless helped consolidate support for PiS among many traditional Polish families. That same year, parliament debated a citizen initiative proposing a five-year prison sentence for any woman found to have had an abortion. The proposal had gained 450,000 signatures and the support of the Church before passing through one parliamentary hurdle. It was eventually thrown out of parliament following mass strikes and protests, as well as international condemnation. [1] The Church also withdrew its support.

The Parliamentary election of October 2019 presented a chance to vote against another term of PiS rule. Pogotowie Graficzne rallied the design community around the cause by requesting posters reminding people of their civic right and duty to vote. “It was really important to participate in these elections because the government is promoting ideas and values that go against civil freedom and tolerance,” says Myćka, whose poster for Pogotowie Graficzne shows a dog dropping a ballot paper into the ballot box from its mouth. The election date is at the top, the X representing both the 10th month and a vote. The double meaning, emphasised by the colour red, makes you double take; if you didn’t get the message the first time, you’ll get it the second.

Myćka admits to having an “inborn weakness” for the Polish School of Posters, with which he shares an affinity for dry humour and formal restraint. In one work, Myćka draws a roll of toilet paper in the shape of Duda’s profile. The phrase “papier do du...y” leaves the viewer to fill in the missing letter that determines whether it reads “dupa” (arse) or “Duda”. The caption reads, “Aaah, looks like we’re out. Ink on paper. Toilet paper.” It may be toilet humour, but the message sticks.

“I often base my compositions on the simplest possible shape; a line, a smear, often applied with ink, brush, pencil or scissors, to evoke additional associations than at first glance,” says Myćka. With brushwork and lettering that recall the painterly scrawl featured in the 70s film posters of Jerzy Czerniawski, Myćka appears to be sending a coded message of hope – that art will always triumph over politics.

Meanwhile, Gosia Herba’s poster of a young woman on her way to vote was displayed in shops and cafes around Warsaw’s city centre in the weeks leading up to the election. Pacing through the centre of town dressed in red flares and a red beret, she is pursued by a speech bubble which reads “I’m going to vote”. “She is independent; she will vote according to her beliefs,” says Herba. “She is aware of her rights and that her voice shapes reality. No man, father, husband, or partner will impose a choice on her.”

Aga Giecko (@agagiecko), June 2020.

Although Herba has an international following, a Polish audience will find her work’s play on proportions familiar, recalling the social realism posters of the 1920s and 30s that elevate the worker to a larger-than-life character. The oversized figure towering over a distant landscape was a stalwart of this period’s advertisements for factories, tourist destinations and political propaganda. One of the most enduring examples of this device is a 1930 commemorative poster by Tadeusz Gronowski that celebrates the tenth anniversary of the “Miracle at the Vistula”, the victorious battle that ended the Polish-Soviet War in 1920. Józef Piłsudski, the hero of the day, soars above the Warsaw cityscape, while abstract shapes and tonal gradation hint at a crowd of supporters at his back. At the time, abstraction in poster design was frowned upon by the state, which favoured more literal representations of the nation that could not hide any subversive metaphors. Nevertheless Gronowski’s approach was able to evade censorship, while also gaining approval for a stylistically daring poster that stretched the boundaries of what was acceptable, and paved the way for the Polish School of Posters.

Viewed in the context of the past 100 years, the towering figure in Herba’s poster is as conventional as Piłsudski, or the idealised workers brandishing blades of wheat in social realism posters. Yet her dress, stance and knowing look send a subtle message of resistance. Meeting our gaze and holding it, she seems to be saying, “it doesn’t have to be like back then. We can vote now.”

On election day, turnout was the highest for a parliamentary election since the first free elections in 1989. PiS retained its majority in the Sejm, the Polish parliament’s lower house, but lost its majority in the Senate as the opposition made gains. It was an election that made the 2020 presidential race narrower than ever. Then, two months before the vote, things took a turn for the worse.

In May, the main opposition party, the centre-right Civic Platform, announced Rafał Trzaskowski as its new candidate. Trzaskowski, the mayor of Warsaw, brought new energy to an election that had lost momentum after having been postponed due to Covid-19. “We need to rebuild our community,” Trzaskowski told supporters at a gathering in Ciechanów in June. “This is what differentiates us from our rivals, who have been conducting a policy of fear and divisions.”

As Trzaskowski gained support from those who feared the country’s democratic institutions were at risk, Duda’s lead in the polls narrowed. In response, he launched a campaign designed to position his opponent as an anti-Polish radical, seizing on his support for LGBTQ+ rights as evidence – in 2019 Trzaskowski was the first mayor of Warsaw to attend the city’s Pride march, and he had permitted discussion of LGBTQ+ issues in schools. Duda’s campaign team published a video spot slandering him with unfavourable footage chopped up in a rapid-cut edit, including a shot of Trzaskowski with LGBTQ+ activists in Warsaw. “Hi Rafał,” it starts. “It’s me, Poland. We don’t know each other very well.” The spot came days after the announcement of a new policy, the so-called “Family Charter”, which included a pledge to “defend the institution of marriage” by preventing same-sex marriage and adoption and which additionally promised to “protect children from LGBT ideology” by banning sex education in schools. The move was part of a concerted campaign by the government and its institutions to re-stage the entire election as a false conflict between queer identity and Polish identity.

“I really thought that the pandemic, the lockdowns, and all the uncertainty had shown everybody that we are all the same, that there are bigger issues, and that nature has no sex or political views,” says Giecko. “Unfortunately the presidential campaign focused on very individual and controversial views, digging into extreme concepts that cannot be discussed without endangering the freedom of another human being.”

Gosia Herba (@gosiaherba), August 2020.

Following the announcement, graphic artist Natalia Łajszczak illustrated the prevailing mood in the country. In her poster, a map of Poland takes on a nebulous shape; its folds form many faces showing a range of emotions. “The statement drew a turbulent social mood in Poland,” she explains. And yet, the map’s vibrant hues send a message of hope; that after every storm comes a rainbow.

“This was a campaign aimed at positioning LGBTQ+ people as enemies of Polish culture,” says Herba. “I just had to show support to my LGBTQ+ friends and their families.” A week before the country went to the polls, Herba’s woman in the red beret and flares came back — this time with a rainbow on her jumper. “I live in a homophobic country where the current president and government are denying humanity to LGBT people. Next week, I’m going to cast my vote. I don’t want to live in a country of hatred and ignorance,” Herba wrote in the accompanying Instagram caption. Many women identified with this image of a strong female and its message of empowerment, even showing up at polling stations on the day dressed as her.

The rainbow also appears in Giecko’s poster, in which she takes us on a fantastical trip to the polling stations of her childhood – an effort to “even slightly counterweight the unprecedented negativity and oppression.” “VOTE!” is graffitied onto the wall, surrounded by sparkles and spray paint marks that could be the remnants of an art class. A ballot box strides across the room with a completed ballot paper sticking out of its top and the stern look of a teacher schooling their pupils. A couple of posters are tacked onto the wall; one shows a flower with a rainbow of petals circling its face, posting a completed ballot paper and high-fiving the ballot box. The other shows a pigeon casting a ballot over a rainbow.

As the election drew closer, other presidential candidates started to pile onto the topic of LGBTQ+ rights in an attempt to gain column inches. Krzysztof Bosak, the ultra-conservative candidate for the Confederation Liberty and Independence party, used an interview with Rzeczpospolita’s weekend supplement, Plus Minus, to argue that “the LGBT movement leads to social depravity and we have a moral obligation to oppose it.” He added that “representatives of these sexual ideologies will stand on the heads of normal people and hound them.” On 7 June, he visited Poznań, where Zuza Kamińska is studying at the city’s University of the Arts. In a speech in the city’s Freedom Square, Bosak claimed that it would be him facing Duda in the second round of the election.

Kamińska, whose Instagram profile is packed with vibrant sketches, protest posters and punchy captions criticising the latest political scandals and advocating for human rights issues, says she is “here for people, not for political reasons.” Her naive, manga-inspired illustration style uses brightly-coloured felt tip pens and creates an uneasy tension with the seriousness of the political issues she comments on. It’s not surprising, then, that LGBTQ+ rights are a recurring theme on her page, or even that there is a painstakingly hand-lettered post outlining the “seven reasons why Andrzej Duda is not and was not my president”. But there’s one work in particular that stands out for its compositional similarity to the towering figures we met earlier. In Jak iść to nigdy na Bosaka (If I must go, then never barefoot / for Bosak), a person strides across the page in fabulous knee-high boots, hands on hips: #drag, the artist notes. Kamińska references the same exaggerated perspective as Herba but, this time, the towering figure has evolved from socialist worker to empowered woman to drag queen. And so the motif is reinvented yet again.

On 13 July, Poland woke up to news from the National Electoral Commission that Duda had won by just 2.4 per cent. A hush fell over Instagram, as Polish designers processed what had happened. Kamińska drew a person with a face mask over their eyes. “Well done Poland,” she wrote. The BBC reported that it had been Poland’s slimmest presidential election victory since the end of Communism in 1989, but it was to be the calm before the storm. “After the election, the situation intensified considerably,” says Myćka.

Zuza Kamińska (@nekrofobia), June 2020.

On 7 August, the day after Duda was officially sworn into office, police arrested 22-year-old trans activist Margot and placed her in pre-trial detention for two months. She is being prosecuted for vandalising a van belonging to Fundacja Pro-prawo do życia (Pro-right to live Foundation), a group that drives around Poland’s city centres broadcasting messages over loudspeakers and displaying large banners that liken the “LGBT lobby” to pedophiles and claim LGBTQ+ people want to teach four-year-olds how to masturbate. In a civil lawsuit brought against the group earlier this year, the Polish court ruled that its messages were lawful since they are “true” and in line with the constitutional right to freedom of speech. Margot was denied contact with her lawyer and the right to post bail. If convicted, she faces a multi-year prison sentence.

Forty-eight other people were arrested that day too. Videos circulating on social media show random passers-by being pulled off the street and pushed into unmarked vans in scenes reminiscent of World War II roundups. An investigation launched by the Polish Commissioner for Human Rights found that some of those arrested were not protestors but merely bystanders, and that police had also insulted and humiliated LGBTQ+ detainees. A Human Rights Watch dispatch stated of Margot’s treatment: “Another demonstration of the crumbling respect for the rule of law in Poland.”

The next day, thousands of people filled the streets around Poland in one of the country’s biggest public displays of support towards its LGBTQ+ community. “Fundamental human rights is not a discussion topic,” says Kamińska. “If you see someone disrespecting them, you have to react. Especially if the person doing it is the president of your country. Everyone should feel safe and free in Poland. That cannot be ignored.”

“I don’t want to live in a country of hatred and ignorance.”

Returning home from the protest in Warsaw, Łajszczak was too full of anger and adrenaline to sleep. At 4am, she sat down at her desk and started to draw. The resulting graphic is a striking visual metaphor for human nature. A gradient rainbow arches over the phrase “Byłam, jestem i będę” (I was, I am and I will be), while storm clouds hover above. A lightning bolt is fused with one of the typographic e caudatas in “będę”.

“I wanted to indirectly address the common (and ignorant) refrain that homosexuality is abnormal and unnatural,” she says. “People using this convoluted argument either forget, don’t know or ignore the fact that our lives are based on a social contract that has nothing to do with naturalness. Just as the rainbow is a natural weather phenomenon, the sexuality spectrum is a natural biological phenomenon and has been with mankind since the dawn of civilisation. The way we approach the LGBTQ+ community as a country is purely the result of this and no other social contract. A contract which, in the case of Poland, should be updated. I was, I am and I will be in your social landscape, so let’s do something about it.”

That same day in Poznań, Myćka was walking home alone when he was brutally attacked by four strangers in the street for no apparent reason. The experience made him reflect on the abuse that minority groups have to face on a daily basis in Poland. “Looking at what is happening in Poland today, where LGBTQ+ people have to struggle to have their right to a normal life recognised, and some people are getting locked up because of it, makes my head hurt more than from those kicks,” he says. While tending to his bruises the next day, he created a graphic in which a pair of handcuffs merges with a rainbow. “I’ve never felt discriminated against because of who I am so I will never understand how hard it is for those people, but I am even more convinced that we have to do everything we can to show our solidarity with those who suffer because of who they are, and stand together against all acts of aggression.”

Grzegorz Myćka (@grzegorz.mycka), 2019.

In the 10 days following Margot’s arrest, Pogotowie Graficzne published 44 posters in response to their impassioned plea. Many of these posters were printed and taken to protests, and many more have been shared and re-shared on social media. Online and offline collided as LGBTQ+ politics crashed into the mainstream. Where once Polish poster designers operated in isolation, limited to their surrounding streets, today’s illustrators are able to put out work for the whole world to see thanks to the internet and social media. Instagram now integrates politics and protest movements with its standard fare of brunches and beach trips, while the platform’s sharing and engagement functionalities facilitate a potential reach far beyond that of a printed poster. While there is a risk that increased exposure will lead to protest fatigue, and a dilution of styles in favour of a homogenous brand of global protest graphics on the part of the designers, the medium’s move into the digital has the potential to further democratise the poster.

Following sustained pressure from Poland’s queer community and its allies, Margot was released from pre-trial detention after three weeks. Activists welcomed the news and rejoiced at the triumph of ordinary citizens over politicians. For now, the situation has calmed down, but there is still much to resolve. “I believe we can all use our platforms to create something positive, show solidarity and unite under a well-designed poster,” says Giecko. “However, I would like to see less politics in our department and more honest work in the political department. In other words – doing our jobs.”

1 On 23 October 2020, a month after Disegno #27 went to press, Poland’s Constitutional Tribunal ruled against abortions in cases of foetal defects, effectively banning all terminations apart from cases of rape, incest or a risk to the pregnant person’s life. Two of the judges on the tribunal had previously been MPs for the PiS.

Words Zosia Swidlicka

Graphics Pogotowie Graficzne

This article was originally published in Disegno #27. To buy the issue, or subscribe to the journal, please visit the online shop.