Site Responsiveness

Max Lamb’s Exercises in Seating 3 brings together chairs Lamb has made over the last 10 years of material experimentation (image: Angus Mill, courtesy of Max Lamb).

In Harrow-on-the-Hill, inside of a former church hall, Max Lamb’s chairs sit in quiet contemplation of one another.

The chairs are arranged in a circle, facing inwards. There are chiseled chairs, stitched chairs, cleft chairs and welded chairs. Chairs in wood, chairs in ceramic, chairs in metal, and chairs in leather, variously animal, pineapple and mycelium. The seats have been arranged chronologically, from 2015 to 2025, but as to where this timeline begins or ends is difficult to say. There are similarities across the designs – particular cuts, constructions and textures that recur and reference one another – but far more frequent are dissimilarities and disjuncts. A chair made from transparent glass sheets peers at an amorphous metallic leather armchair; a marble block carved into a rugged cowlick glances at a softly rounded stool formed from curving blue tiles, like the bottom of a swimming pool grown into functional shape. Serene in their circle, the chairs are all different, yet together assemble into an archive of the material and making experiments that Lamb has executed over the past decade.

Exercises in Seating 3 is the latest iteration of Lamb’s semi-regular chronicling of his own practice, as told through the seat designs that punctuate his wider work across furniture and objects. The first iteration of the exhibition was staged in Milan’s Garage Sanremo (before later travelling to the Art Institute of Chicago), bringing together 41 seats from 2006 to 2015, while its sequel settled in Hyères’s Villa Noailles, displaying work from 2006 to 2016. If the first two editions of the exhibition arose in quick succession, the third has been longer in the making, but, happily, arrives in conjunction with a comprehensive new book covering the trilogy of exhibitions, published by Dent-De-Leone. “Ten years is probably a little bit long, but equally, less than ten years feels too short,” Lamb explains. “It’s something that I feel I need to do.”

The chairs in the exhibition speak to central preoccupations of Lamb’s work, not least his attentiveness to landscape (whether natural or industrial) and the capacity for design to express both a sense of place and the activity said place encompasses through material. The designs on display – be they soft enveloping armchairs; carved occasional chairs; or even a stitched football (“People sit on footballs all the time”) – also serve as research projects for Lamb, providing opportunities for him to experiment with new making techniques and approaches towards material. The results may be varied in their materiality, form and execution, but each reveals a central tenet of Lamb’s work: “With all of these pieces, I'd like to think that I've let the material speak for itself,” he says.

The chronological arrangement of the chairs emphasises the manner in which Lamb leaps between different materials from one project to the next (image: Angus Mill).

The pieces in Exercises in Seating 3 reflect Lamb as a designer essentially concerned with material – its extraction, its character and its entanglements, be they environmental, social or industrial. Yet in comparison to many of his peers, Lamb’s work places significant attention on making as an end in itself, and not simply a means of achieving new designs. The seats are all fully fleshed objects that stand independently of their creator, with most sold around the world through Gallery FUMI and Salon 94 Design, yet there is also a sense in which the finished designs that Lamb reaches are a byproduct of their own making. As opposed to material being a mere means to an end, Lamb’s work frames making itself as the principal source of value in his work, and the route through which he can better understand the materials that surround us. As Lamb notes, “the pleasure is in the making.”

This approach is given an additional wrinkle in Exercises in Seating 3. Rather than a formal exhibition space, the hall in which it is based is a part of Lamb’s own home, which he and his partner, designer Gemma Holt, have been restoring and adapting since 2018. Built in 1884 by architect E.S. Prior as a church hall, the space was most recently used as a plastics factory for the manufacturing of products such as Scalextric shells. While work on the space remains ongoing, with Holt and Lamb exploring ways through which it might serve as an ongoing community resource, Exercises in Seating 3 marks the first time that it has been opened since the machinery and detritus of the former factory were cleared out. Like the seats that it contains, the space is itself an experiment in making, and a place whose current usage is steeped in its own history, social context and the materials it once contained. “We want it to become a public space,” Lamb explains. “And that's why this is such a key moment in the history of this building and for our recent history as custodians of it.”

Below, Lamb discusses the exhibition and his approach towards design, making and materials.

The exhibition is hosted in a part of Lamb’s own home, which formerly served as a church hall and a plastics factory, and is now being restored and adapted into a community-focused space (image: Angus Mill).

Disegno I'm curious as to why you stage Exercises in Seating as a recurring series of exhibitions. Is the motivation for Exercises in Seating 3 the same as it was for Exercises in Seating 1?

Max Lamb Exactly the same – which is a very personal thing. It ends up being public as an exhibition, but the motivation for doing it is private in that it gives me an opportunity to gather and spend time with the work – a moment to reflect. I'm not normally a reflective person. I'm always moving forwards; I'm always rushing and scrambling.

Disegno You’re very productive. There are 40 chairs in this room dating from the last 10 years, and that represents only a fraction of the work you’ve done in that time.

Max I am, which is why it's necessary to have these pauses. It's a moment that works as mental archiving and analysis. It gives me an opportunity to pause, breathe, enjoy, reflect, and it also helps me to plan. I really need to do that because the exhibition acts as something like a filter. In the book we’ve made to accompany the show, there is an index of projects and I catalogue all of my projects by number. So whenever a project begins, whenever the first conversation happens or the first email is received, I start a new project folder and assign it a number.

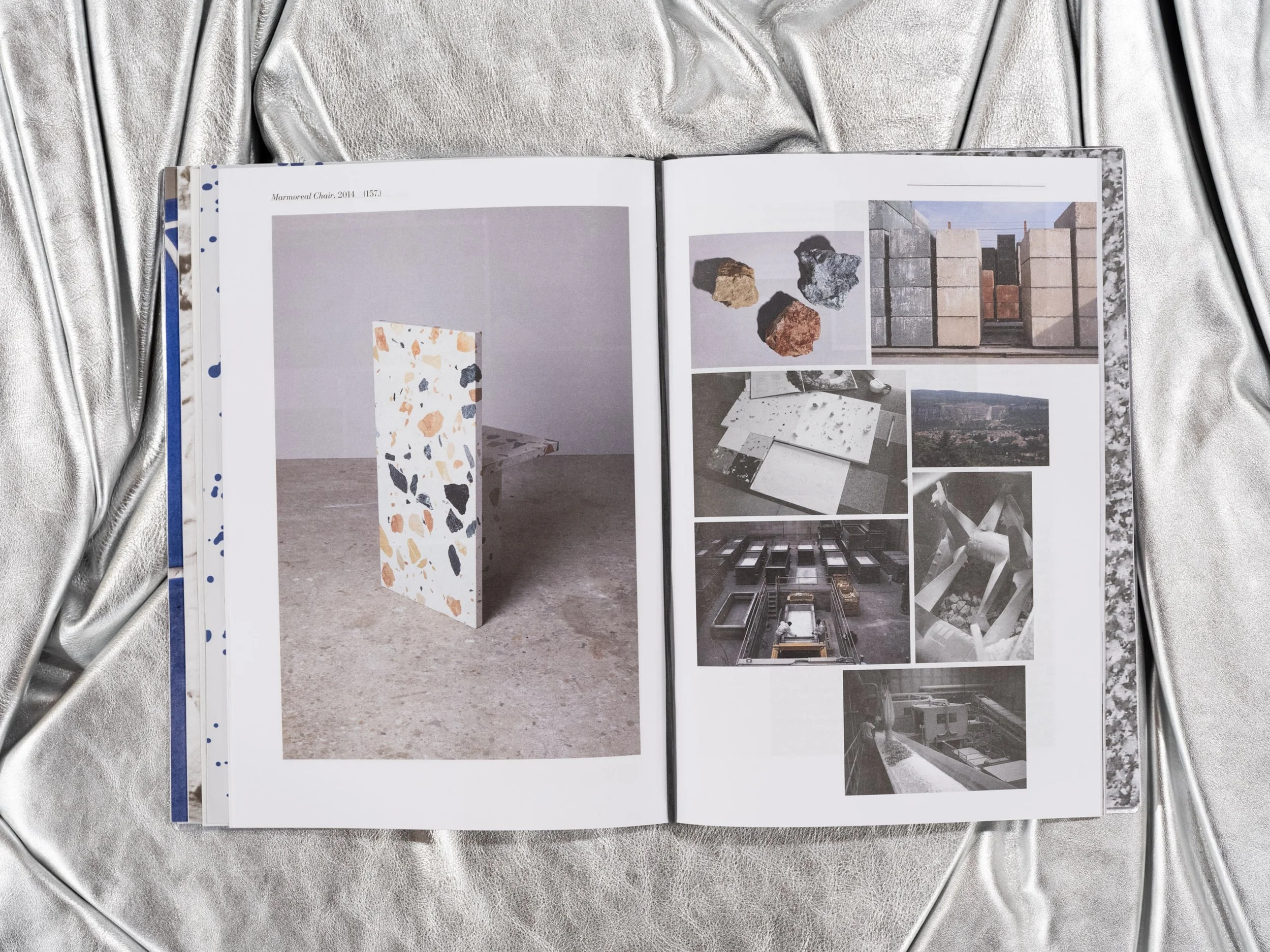

A book accompanying the exhibition, Exercises in Seating 3, provides behind-the-scenes information about each chair’s construction (image: Angus Mill).

Disegno Omer Arbel from Bocci does the same – every project has a chronological number dating to their conception, which means that they don’t always emerge in the world in that order.

Max That's true here too. So SRM Plastic Child's Chair is project number 556, for example. The project was conceived in 2018 but only materialised in 2025. It's taken seven years to get to the point, and that's not because I wasn't developing it. It was just a project that was on the back burner, or which was slowly incubating. It was dependent on lots of other things.

Disegno In what way?

Max It's made using plastic from this hall. So the moment we got the keys to this place, we realised what kind of undertaking we had to clear out all of the machinery and detritus left behind by the previous owner. Some of that detritus was plastic in the form of injection-moulded products: sprues, which are the pieces cut off as part of the process, and nurdles, which are pellets. The machinery sadly had to be scrapped because it was obsolete, but the plastic had value somehow, from a sentimental and historical standpoint. Each of these injection-moulded products had a story to tell, and I wanted to save that. I saw them as raw material and wanted to do something with that, but it was a whole process. It wasn't like I had a clear vision for what it was going to become, but I knew that I wanted to do something.

Image: Angus Mill.

Disegno Is that common?

Max There are other examples in the exhibition. So the granite Feather and Wedge Chair dates from 2020 to 2025. “Feather and Wedge” is the process for making it – you drill or hammer little grooves into the granite, and then you hammer in two feathers, which are two slivers of metal, and a wedge. As you hammer the wedges into the feathers, it forces them outwards, which splits the rock. I've made three versions of this chair now, but they often fail during the making. You do a lot of work to try and split the stone and then a leg breaks off, or the back shears in half, or it doesn't split how you want it to. The first one that I did manage to make back in 2020 was something I really wanted in the exhibition, but it’s in New York and is also big and cumbersome. So I’ve made a cuter version instead: a smaller, more manageable, church hall-sized version. This summer we spent a week in Italy as a family holiday, where I happened to find a stone yard and quarry where I could make that.

Disegno Do you do that that wherever you go? In all of your work, site is important and the pieces are nearly always a response to a particular place and its materials. You mention finding that quarry on holiday – are you always on the lookout?

Max Well, I used to skateboard when I was younger. I never became particularly good, but it was interesting because I explored the landscape with a skater's eye.

Disegno You're attentive to what you can grind on and things like that?

Max Exactly. You’re engaged. I'm looking at the landscape and, even when I don't have my board, I'm walking around thinking about what would be cool to grind or ollie. I could probably apply that sort of analogy to other interests. Now, I explore the landscape as a designer and maker, and as somebody who's looking at things to extract – whether it's a raw material, an idea, or just a tool. Growing up, for example, I spent a lot of time on my grandpa's farm, and I was always interested in the machinery. Farm machinery is designed to do one thing, but could it be used to do something else instead? So there’s a chair in the exhibition called Rosa Aurora, which is a pink marble from Portugal. Although it’s not directly explicit in its form, there are details in that chair which would not be possible to generate in any way other than using the tools of the site from which it’s from.

Image: Angus Mill.

Disegno How so?

Max It was the first time that I had worked in a quarry that was using a machine with a pneumatic hammer drill – the kind you'd see on the road breaking up concrete. They used it here to break up bigger blocks of rock, and it’s usually used on waste rock to make it small enough to put through a crusher to make dust or aggregates. So in that quarry I found a block of stone which had exactly the colour I wanted, but it was too big. Generally, the quarries I go to are dimension quarries, which means that they're cutting out blocks of stone, as opposed to an aggregate quarry where they're using explosives to blow up the ground. Those are the quarries where they're extracting gravel and hardcore and rocks for asphalt and concrete production or whatever. So usually as a designer you go to a dimension quarry, and the prized material is these perfect blocks of stone cut from random shaped mountains or holes in the ground. But in order to get to that, there’s all this other stone on the periphery that is essentially waste or spoil. And I like spoil.

Disegno Rose Aurora was made from spoil?

Max It was. A boulder that was absolutely monstrous, which I loved. I'd seen this pneumatic machine further down the quarry breaking up the blocks, so I wondered if I could use it to break the boulder into smaller pieces that were almost chair-sized. So there’s a big bruise on the finished chair, which was created by that machine smashing that rock into smaller rocks so I could then cut chairs out of it. Obviously I'm going to a quarry knowing that I'm going to create work, so maybe that's not a great example, but certainly whenever I travel anywhere nowadays, I’m looking for things. Whether it’s to the Tube station and I see tree surgeons hired to cut down dead trees or cardboard boxes on the street, everything is an opportunity.

Disegno Cardboard boxes being what you used to create the furniture for your Box exhibition with Gallery FUMI in 2023.

Max The majority of those were made with boxes coming into the studio that I was collapsing and stacking up, but there were other boxes that came from outside the pub or wherever else I went out scrounging. Word got around that I was on the lookout. Anyway, when we moved here, we had a huge amount of box material, but you can never really have too much, because the more you have, the more choice you have, and the more you can start to find relationships between different sized boxes to start nesting them together.

Disegno Box Chair is in this exhibition, so how do you feel when you look back and see your work set out like this? Some designers might be analytical, and almost review their work, whereas others might say that they can’t pass judgment in that way – they can’t assess the work or get critical distance from it, because seeing the piece just makes them think about how and why it was created.

Max It's a really good question, because when I'm making something it is all about the process, and this kind of responsiveness to what is appearing in front of my eyes or in my hands or at the end of a tool operated by my hand. Of course, I’m thinking about the end result throughout the process, but at the moment that it's made, I'm looking for the next thing. I'm looking for the next lump of raw material to start manipulating and transforming into a new piece. So my team don't get many compliments from me, because I never dwell. The piece is done. Great. Photograph it, put a blanket over it, wrap it up, ship it out. Let's make something else.

Disegno Why is that?

Max Because the pleasure is in the making. For me, the enjoyment is the act of doing, not the act of finishing. There's obviously a short-lived satisfaction in having finished a piece, but the greatest satisfaction is in the physical activity. The reason that my team don't get many compliments from me is because I never give myself compliments either. It's just like, “Right, next.” That’s almost frantic. I don’t know why, but I've always been like that. I'm so restless generally.

Disegno It's interesting, because whenever I read writing about your work, people reach for quite familiar language: the pieces are always described as “primal” or “elemental” or whatever, with the idea that you have a very recognisable and specific aesthetic. But if you look around this room, it’s actually full of very different things.

Max It really is. It’s all very, very different. When people look at someone’s work, you're rarely looking at a collection in its entirety. You’re more often seeing an isolated piece in an exhibition. I think I like the idea that my work may be definable, but actually I don't really know how to define it. I mean, I would say that my work is easy, as in I find it easy to make because it just happens. There's a physical challenge, but the mental challenge is almost automatic because of the responsiveness to what is happening.There's a lot of spontaneity in my work.

“There’s only so much control that I want to inflict. With all of these pieces, I’d like to think that I’ve let the material speak for itself. It does what it wants, which is why they all end up being fundamentally different.”

Disegno Something nice about your design is that it always looks like it's just trying to be itself. The individual pieces don’t feel like they’re reaching for any particular style.

Max They almost make themselves somehow. Obviously I'm the one in control of the decisions, but those decisions are informed by what's happening in front of me, and what's happening in front of me is that the material is doing something. Of course, sometimes that is preconceived – I’m not saying it's happening literally at the moment where I’m chiseling or gouging a piece of wood – but there is a responsiveness. So the chair you’re sitting on [Split Wood Chair] requires joinery of all of these beautifully square pieces of pine wood, but then there’s the un-squaring of those pieces’ edges, which is a much more physical, out of control process done with a froe and mallet, which you use to cleave the wood. In fact, testament to its physicality is that there is not a mallet on this planet that doesn't get destroyed when I'm making these pieces. It's a really beautiful dance between human and material, where sometimes you think you’re winning when the froe bites, but then the material resists. Pine has so much personality and so many grain directions and knots, and you have to remember that this is not high grade pine; it’s builders’ grade pine for stud walling. The knottiness has a mind of its own, so the knots in the wood and the grain of the wood win that battle with the human. To make matters even worse, rather than one big chunk of pine, I'm joining 100 pieces together, each of which wants to go in a different direction when it starts splitting. When you start putting the froe in, you face resistance. You start to eat into it and then the grain and the knots take over. I have a sketch of an idea, a theory of an idea, but after your first split, you don't know where that split will end. You realise, “Oh, blimey, I started here, but the splits gone there.” So your next split needs to respond to that. I'm always responding to what is happening, which makes it difficult to pass the reins to somebody else, or outsource production.

Disegno It’s a bit like an acting performance. Two actors playing the same role will interpret and perform it very differently.

Max That’s the mentality of letting material do its thing. There's only so much control that I want to inflict. With all of these pieces, I'd like to think that I've let the material speak for itself. It does what it wants, which is why they all end up being fundamentally different. There’s a glass chair, there’s a polystyrene chair, a ceramic chair, a wood chair, a granite chair, all of which have been made through that process of material speaking for itself. They’ve all done what they wanted to do, even if it's still led by me.

Image: Angus Mill.

Disegno They are all very different, but the obvious similarity would be that they’re all chairs. Why do you focus on that typology? Because someone might say that they want to be responsive to site and material, and a corollary of that is that they want to make a different type of object each time.

Max Well, in a way the seating on display here are the gaps between the projects. They are projects in their own right, but they're also a means to an end, and part of the process of building up a library of knowledge and skills and tools to be a designer of objects. Generally, the chair is an archetype that is a very good test of a material – its capabilities, its wants, and the methods for transforming said material. So there are different ways of making clay furniture and ceramic furniture, and there are different ways of making wood seating – we’ve got seven wooden chairs in the exhibition, all of which are fundamentally different. But seating gives me a focus when it comes to exploring the possibilities of a material, so I can end up with this huge library of knowledge and collection of pieces. They’re like my reference library, but they are also gaps, because this exhibition goes from project 256 to project 648. That’s nearly 400 projects, but only 40 chairs, so its about 10 per cent of my last 10 years’ work in this room. I mean, it's kind of in the title: “Exercises in Seating”. The seating gives me direction, focus and a way of making direct comparisons. You know, I've made polystyrene vases, I've made ceramic cups, I’ve made spun metal planters. Each of the materials are different, each of the processes are different, and each of the objects and functions of those objects are different. It's good to have one common thread between all of these exercises and experiments, so that the feedback is the same.

Disegno When you say that the reason you do the exhibition is to reflect, what do you mean by that? Someone might interpret that as saying that it can serve as a kind of course correction, where you plan ahead based on what you’ve done, but I get the impression that that isn’t necessarily what you meant.

Max It's not what I meant, but I would say that it is part of it. It’s multiple layers of benefit, but there is still that question of what I mean exactly. I guess going back to what I said before, once I finish a piece, I'm done, I'm over it, and I move on to something else – and often something that is very far removed from what I've just done. You get that sense even just looking around this room, because the chairs are displayed in chronological order. You can see that I made a chair out of glulam wood, which is right next to a tufted wool chair.

Image: Angus Mill.

Disegno Very few of the chairs directly alongside one another look similar.

Max True, apart from those two [Ghost Chair and 6 x 8 Chair], because one of those is the polystyrene prototype of the other, which I then made out of cedar – the polystyrene being a very cheap, ephemeral and highly synthetic material compared to the final piece, which was made out of an incredibly expensive and valuable piece of old-growth western red cedar from Canada. The idea of making the kind of extreme incision that the 6 x 8 series needs straight into a piece of western red cedar was something I did not have the confidence to do. I am gung-ho when I can afford to be, and I was with the polystyrene, but I wasn’t with the wood. With that polystyrene seat, I would have cut it five times in the wrong place to learn that it was wrong. But I could then glue it back together again and recut. Western red cedar requires a greater level of accuracy and focus and confidence, whereas I can be more liberal in polystyrene. So there is obviously a direct relationship between those two, but everything else has a disparity between the pieces in sequence. But it’s interesting for me to see those differences. My ceramic Crockery Chair started in 2018 and the first one came out the kiln in 2024, so it was developed over a long period of time. But I began that project at the same time as my 60 Chair project. What’s weird to me is that, although both were conceived pretty much in parallel or in direct sequence, they didn't materialise until years apart. This exhibition is the only way I can gain that kind of insight into my practice.

Disegno It’s interesting that they’re curated and exhibited as a circle, with all of the chairs looking at one another. There’s a parity and flatness to it, whereas typically an exhibition would award priority to certain pieces over others.

Max That is very conscious: the non-hierarchical arrangement and the fact that there is no beginning or end. Although they are chronological, you don't necessarily know which the earliest chair is versus the most recent one. They all inwardly look at one another and become part of this overarching conversation and representation of me and my approach to making things.

Image: Angus Mill.

Disegno It’s accentuated by the setting in this edition. Because of the history of this space as a church hall, it makes me think of a Quaker meeting – a circle of chairs where you can sit in silence and reflect.

Max Exactly. I mean, I think about this all the time: I always think about my work and what it's doing at that exact moment. I do the same thing with humans. I'm imagining what you are seeing right now, the fact that we're sharing this moment together, but as soon as you leave, you're going to be seeing things and experiencing things that I'm not. I have the same with my furniture. You know, I've made thousands of pieces of furniture, and they are all out there somewhere, existing, experiencing something. I know they don't have minds or brains or feelings, but they are, in some cases, living material, breathing material. I think about that, and I think about this place and how all these chairs, when you turn the lights down at night and go to sleep, still exist. Everything still exists in this world. They almost are like people, with feelings and opinions. And, not to get all weird about it, they all certainly have something to say.

Exercises in Seating 3 continues Saturday 25 and Sunday 26 October, and Saturday 1 and Sunday 2 November, 12–6pm. Please contact studio@maxlamb.org to make an appointment to view the exhibition.

Words Oli Stratford