LDF 2025 Round Up

Design gallery Slancha’s exhibition of objects inspired by car boot sales (image: Slancha).

London Design Festival (LDF) 2025 took place from 13 to 21 September, and the Disegno team scampered all over the city to see the exhibitions, launches and projects on offer.

Our round up of some of the most intriguing events we saw includes insertable objects, car boot sales, camping tents, decomposing packaging, and much more.

Design Everything created a portable exhibition of 36 chairs inside of a Luton van, which pulled up in different districts of the city for exhibitions, workshops and talks (image: Design Everything).

New Seats; New Table

It is a truth universally acknowledged that the world does not need more chairs, yet designers continue to produce new iterations of the format en masse, regardless of the typology’s creative opportunities having been well mined for decades. Despite this, one of the freshest, most relevant, and pointed exhibitions of the 2025 London Design Festival saw 36 designers turn their hand to the format once more – with spectacular results. A Seat at the Table is a roving exhibition by the not-for-profit Design Everything collective, an initiative dedicated to platforming new voices, allowing them to exhibit their work and connect with diverse audiences during the festival. Based off an open call, 36 designers were selected to create seats for the show (the only requirements for which pertained to dimensions), which toured the capital in the back of a Luton van, pulling up in different districts for exhibitions, workshops, talks and more – an open format designed around Design Everything’s emphasis on access. It made for a daring, delightful and kinetic show, with the Luton van opening its tarpaulin sides to reveal the treasures within, with chairs taken out to form impromptu and inventive public seating, and guests welcomed into the van to explore its portable archive. The show succeeded, however, not only because the strength of the seats demonstrated the talent and inventiveness of an exciting new generation of designers (whose contributions ranged from material showcases to technical exercises; witty near-readymades to cultural critiques), but also through the ingenuity and social mission of the platform itself. Design Everything (steered by Lewis Duckworth, Tabatha Pearce Chedier, Sammi Cherryman, Eleanor Murphy and Jacob Marks) is notable as a project that not only produces new work, but which also designs the conditions through which new designers might support one another and create opportunities for themselves – no small task in a field more adept at venerating the established than welcoming the unheralded. While the seats created as part of the initiative are wonderful – and ably stand alone regardless of the context in which they were created – it is the platform itself that is most laudable: rather than simply feed their chairs into the existing system, Design Everything has created a new table around which they (and perhaps further works in future) might gather.

Students from Store’s after school clubs, photographed with Attua Aparicio Torinos and Oscar Lessing (image: Katie Kamara).

Early Access

If Design Everything sought to create new pathways into the field for early-stage practitioners, Store in Kings Cross targeted an earlier point in the talent pipeline, exhibiting a project that has been co-designed by local state school students. Titled This Bench has Legs, the project saw designers Attua Aparicio Torinos and Oscar Lessing work with a group of 14-18 year olds to design and cast an aluminium leg element for public benches – an initiative that recalls the designers’ earlier Wealdstone Leg project. A 1:1 prototype, the bench element is produced using recycled material formed into a pleasingly sinuous irregular hexagon, a decision that allows for the legs to simply be rotated to create benches of different heights, rather than requiring different elements for different benches. The prototype is a beautiful and ingenious solution (which now deserves further funding to achieve a final system that could be rolled out), but equally commendable is Store’s work to involve young people within design, and empower them to feel that they have a vital role to play in shaping the public realm. While Aparicio Torinos and Lessing may have led the workshop to develop the bench, the students also worked with designers James Shaw, Marina Dragomirova of Studio Furthermore, Livia Lauber, and Dawn Bendick of Observatory Studio across Store’s series of After School Clubs and Summer Schools. The fruits of these workshops were exhibited within Store’s space in Kings Cross, with the benches placed outside, and the dialogue between the two was compelling – the experiments in manipulating glass, plastic and public space that were led in these workshops becoming apparent in the fluidity and resourcefulness of the bench. Over the course of the initiative, Store and its participating designers have allowed the students to roam widely and freely, creating a body of work whose outputs have fed back into itself, with lessons learned in one session informing those gleaned from later workshops. While the bench is a compelling culmination for the project to date, of more import is the wider Store mission into which it has slotted: “supporting more young people from underrepresented backgrounds applying to creative courses, and addressing the social imbalance in art, design and architecture education.”

Heirloom’s display of insertable objects included a Kegel toner, earbuds, a menstrual sponge and a retainer (image: Heirloom).

Out of Orifice

Everybody loves a game, and Heirloom studio’s Out of Orifice exhibition invited the silliest type of play: guessing where an object would go inside the body. The show featured an oval table filled with insertable objects, some which are easy to identify (lollipops and cotton swabs, for example) and others which left visitors with no choice but to consult the online map of answers (a bulb syringe that removes snot from a child’s nose). The display was accompanied by typographic posters by Studio Frith inspired by the objects’ instruction manuals, with some featuring explicit messages such as “Spread Your Labia” and “Lubricate if Needed” and others touting grandmotherly advice such as “Look Up” and “Chew Thoroughly”, emphasising the varied ways in which bodily orifices are treated and used. Created to display the research the studio conducted while working on a catheter design project, the exhibition visually explored the differences between objects designed for health and for pleasure. Medical objects such as inhalers and sperm injectors are almost all clear or light blue, while sex toys tend to take on purple or fuchsia tones which are also shared by consumer-facing medical products such as menstrual sponges and cups. The exhibition asked what medical design can learn from the silky materials, ergonomic design and joyful tones of objects designed for pleasure, while raising questions around how to maintain boundaries between the medical and the erogenous, and avoid falling into gendered tropes.

Design gallery Slancha’s exhibition was themed around a car boot sale, featuring works inspired by reuse, memory and narrative (image: Slancha).

Car Boot Sale

“For us, car boot sales have always embodied chance, community, and a kind of quiet chaos,” design gallery Slancha wrote in the introductory text for its exhibition Car Boot Sale, a description which could equally apply to the London Design Festival itself. While the exhibition’s theme highlighted the similarities between the two events, which both value fortuitous meetings with people and objects, it also diverged from the status quo by placing design in a context which values narrative and memory over polish and cohesiveness. An open-booted car greeted visitors as they walked in, and all of the designers’ lamps, stools, spoons, vases, ashtrays and more were displayed amongst patterned rugs and crates sourced from car boot sales. Many of the pieces in the show were made from reclaimed objects or materials – Jake Robertson’s pendant lamp is made from a polka-dotted aluminium off-cut, for example, while Studio East x East’s design patched together a chair, table and shelf into a stair-like structure that inspired the same bemusement that car boot finds often evoke. Other pieces spoke to the gaudiness of a car boot sale, such as George Exon’s aluminium fruit bowl designed to look like a star-shaped price sticker, or simply channeled the event’s magpie-like energy, such as Iona Mcvean’s ceramic lamp designed to look like a minke skull found while beach scraping. The show invited reflection on the qualities that make a design worthy of being sold, cherished, and resold again – qualities which include not only sturdiness and history, but a pleasing sense of oddness.

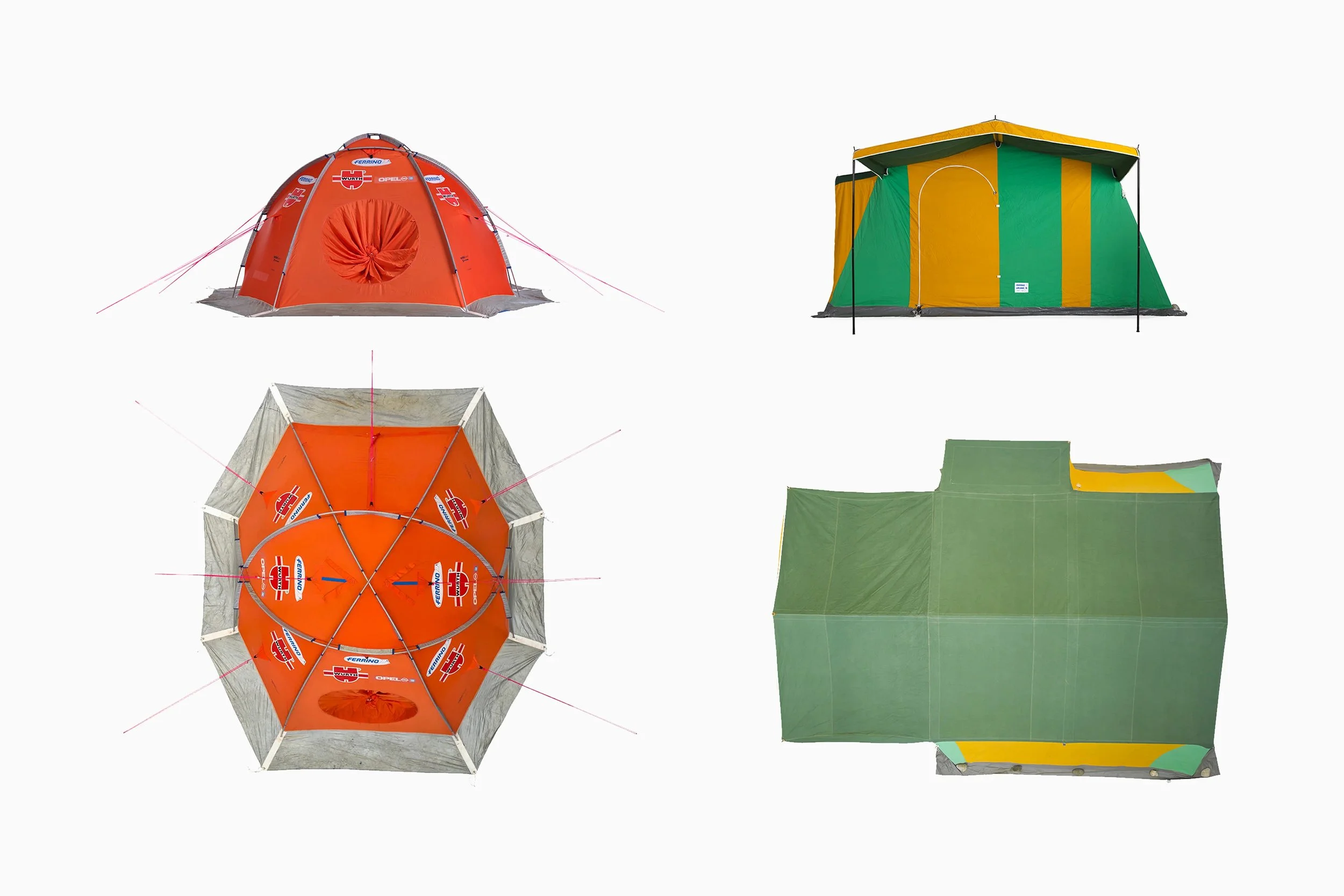

Collection Typologie’s exhibition delved into the design history of the camping tent (image: Collection Typologie).

Gone Camping

Revelling in the design history of a particular object is a passion shared by both Jasper Morrison and French design collective Collection Typologie. Morrison’s previous LDF exhibitions have included shows focused exclusively on drinking glasses, sticky tapes, and carved wooden spoons, while Collection Typologie’s publications have examined the wine bottle, the cork stopper and the wooden crate. After launching the first ever edition, focused on the pétanque ball, at Morrison’s shop back in 2017, the collective have returned this year with a publication and exhibition surrounding their latest fascination: the camping tent. In contrast to Morrison and Typologie’s previous objects of interest, the tent has more wide-ranging sociopolitical implications, something the exhibition acknowledged through archival images that ranged from pictures of traditional American dwellings and boy scout campsites, to Roman military camps and groups of unhoused people sheltering under a bridge. “Even more than the single-material objects studied in previous Typologie reviews, this composite object makes us aware of the complex nature of the things that surround us,” the collective wrote in the exhibition text, describing how tents are used for both shelter and leisure, and are often designed in the West but produced in Southeast Asia. Despite the seriousness of the tent’s symbolism, however, the display retained the collector-like aesthetic of previous exhibitions, delighting in details such as tent pegs made from rustic wood and tent models made by manufacturer Ferrino, whose tiny zippers and crinkled rolls of fabric would make a wonderfully outdoorsy dollhouse.

Morrama’s Eco Flo cassette, an alternative to plastic lateral flow tests made from paper-like cellulose, is designed to decompose (image: Elizabeth Lock).

Designed to Decompose

Lateral flow tests and deodorant packaging sat in jars full of soil at design studio Morrama’s exhibition From the Group Up, each one flaked and papery as they decomposed. “At the moment it feels like we’ve just pushed everything into one bucket, where we make things out of materials that will survive any situation,” said Jo Barnard, founder and creative director of the studio, “even though these materials have a shelf life that’s far beyond the food or cosmetics or consumer products that’s inside it.” Morrama’s show interrogated whether design always needs to be built to last, displaying pieces designed by co-curator of the exhibition Earthmade, such as a portable laptop charger whose case is made from a bamboo-based plastic alternative which shares the same short lifespan as the battery it holds. The exhibition also explored Morrama’s projects using bio-based materials, including the Eco-Flo cassette, an alternative to plastic lateral flow tests made out of paper-like cellulose, and Kibu, a newly launched brand which creates 3D-printed headphones for kids out of plant-based PLA. Throughout the show, materials are shown in their trajectory from powdery fibres into plasticky pellets, and from sleek products into deteriorating husks. The display also shows Morrama’s iterative design process, demonstrating the process of switching Kibu’s artificial colours to earthy hues produced by red clay or wheat fibres, and displaying early experiments with making the headphones out of compostable PHA polymer. “We need to consider what should be designed to be permanent and to be loved and to be cherished, and what is designed to have a function in that moment, to help us in our lives and then fade back into the earth,” Barnard said.

Andu Masebo traced the influences behind his new metal stool, from toasters to makeup swatches and travel reciepts to technical drawings (image: Studio Stagg).

Tracing an Idea

“The design industry requires ownership of an idea so you can package it, sell it and make money from it, and there’s also some level of competition which means that shouting out other people doesn’t serve you,” Andu Masebo said. “But I think lots of people are inspired by their peers and people who went before them.” In order to honour the lineage that lies behind every design, Masebo’s display traced the origin of his new stool, which is made up of two aluminium pieces shaped like oversized cake tins. Wherever possible, Masebo credits his inspirations by name, from OK-RM’s images of boxes and wood stumps being used as temporary seating solutions, to Enzo Mari’s vase with cones of glass in the middle like a flower stamen. But many of Masebo’s inspirations are just the ephemera of everyday life: manhole covers, stacks of pans and cutlery, and samples of eyeshadow and nail polish. “My background was in operating machines, learning about materials and understanding how processes can be used to make products,” Masebo explained. “So I’m not looking at interior palettes or swatches, I’m looking at car finishes or nails or how makeup is applied.” Much like Masebo’s previous LDF exhibition, Making Room, which offered a series of workshops to the general public to make objects that slowly furnished a room, the show was designed to evolve with its audience. “I’ve added to the wall things that have happened in this room,” he said, describing how a visitor came in the day before and shared their memories of Delph, the town where the stool was manufactured. The show peeled back the curtain on Masebo’s design process while demonstrating how a designer’s understanding of a product is continuously evolving, even after it has been released into the world. “I really wanted to show the reality of what it takes to make something,” Masebo said. “It’s messy, it’s chaos, it happens at the last minute, and actually, a lot of the rationale comes afterwards.”

Tione Trice and Ronan Mckenzie’s show brought together works from contemporary artists and designers, creating a space that resembled a carefully curated home (image: Andy Stagg).

Aspirational Home

“The show title, Mirroring Dialogue, isn’t just a title,” New York-based curator Tione Trice said. “It’s about exploring how Black people from all around the world are producing similar works without coming into contact with each other.” Co-curated with London-based fashion designer Ronan Mckenzie, Trice’s show featured pieces from designers from across the African diaspora, highlighting similarities across different mediums and geographies. “I think it’s about the intention behind the practice,” Trice said, using the example of artist Beoncia Dunn’s photographs of people dancing, and designer Myles Igwe’s blue tapestries printed with archival images of women during a ceremony in Nigeria. “I think the common thread between those two is definitely their faith – they both have a very strong faith base, and I think it encourages them to produce in the cleanest of ways, and to constantly dig for the positive.” The show looked like a beautifully curated living room, with Trice’s blue coat with wide lapels inspired by vintage African American tailoring strewn on the floor upstairs, and Mckenzie and Jobe Burns’ pelvis-shaped chair inviting visitors to recline and run their hands across the cushion’s raised embroidery, which is designed to resemble keloid scars. “We’re all having conversations about space, land and housing right now, in different parts of the world,” Trice said. “We wanted to take this opportunity to create an aspirational home, where someone who is in transition could come and aspire to live in this way, to have this sensibility. That is the truth of the show – home, safety, comfort, familial connection and heirloom.”

Ryunosuke Okazaki’s orchid-like sculptural garments are inspired by pottery from Japan’s Jomon era (image: Peter Kelleher for the V&A).

V&A in Bloom

The V&A can usually be relied upon to host some of LDF’s more striking installations, and this year was no different, with the gallery featuring Alicja Patanowska’s rippled ceramic seating installation trickling with fountains in the outside courtyard, and Ramzi Mallat’s display of colourful glass shaped like Lebanese pastries near the entrance hall. But the gallery’s most intriguing display was tucked away in a dedicated room, which was filled with towering orchid-shaped garments that created scribbles of colour like flowers splashed across a field. Working intuitively and without planning a design in advance, Ryunosuke Okazaki threads polyester bones through strips of velvety velour fabric, creating curvaceous and symmetrical compositions that are inspired by pottery from Japan’s Jomon era. An example of an earthenware pot from the V&A’s collections demonstrated the intricate coiled details Okazaki references, and is among the earliest ceramics ever made. Okazaki’s creations, however, are distinctly futuristic, their regal exoskeletons embodying the mixture of ancient and contemporary which makes the V&A itself so engaging.

Words Oli Stratford and Helen Gonzalez Brown