Futuristic Repair

The Textiles Circularity Centre have developed a new method of repairing clothes using 3D printed bacterial cellulose made out of textile waste (image: Textiles Circularity Centre).

Think about the clothes in your wardrobe. Picture those you love most, the ones so worn that their knees are thin, slightly frayed at the cuffs. You know which ones I mean: you’ve had them for years, a slight stain, maybe, but you just can’t bear to part with them, repaired by hand, perhaps, patched. Or what about those that are damaged beyond repair, ripped, stretched. How do you get rid of those clothes in a way that is sustainable?

This is something I have been asking myself recently, just off the back of moving house. I have been faced with a wardrobe of clothing in varying degrees of disrepair, many with signs of my own mending. I resold as many as I could, but eventually the stragglers had to go to charity. After more trips to clothing donation bins than I would care to admit, themselves often already overflowing with other donations, it became impossible to quell that niggling thought – where are these clothes really going?

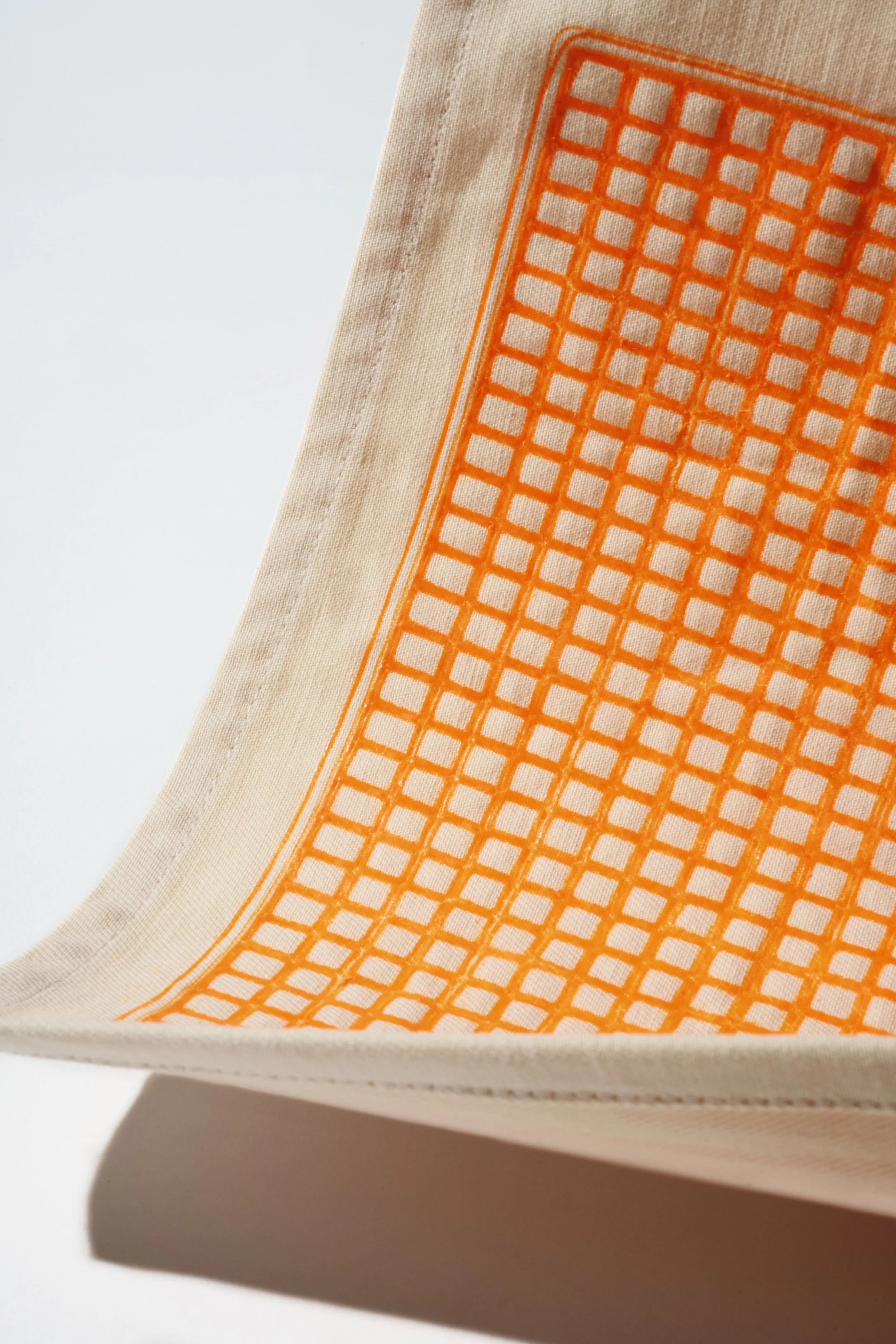

The designs are hyper visible, rather than being hidden away as is often the case in traditional repair (image: Textile Circularity Centre).

The Textiles Circularity Centre began as an exploration of this kind of clothing waste, or, rather, an unravelling of the current system on which it relies. Funded by UKRI, the UK government’s fund for research and innovation, the centre was tasked with designing a model for a new pathway in which waste can become a valuable resource for the textiles industry, and not, as it currently is, an insurmountable problem. Senior research fellow Miriam Ribul and postdoctoral researcher Roberta Morrow, both of whom are based at London’s Royal College of Art and sit within the Materials Circularity research strand of the wider Textiles Circularity Centre, began researching the potential uses of a material called bacterial cellulose, which is created through a recycling process developed by the University of York. In this process, enzymes and bacteria are used to convert any cellulose-based waste – such as clothing, straw, or even used pizza boxes – into a biomaterial similar to viscose or lyocell, which are usually made from virgin wood pulp.

A loose thread upon which to tug, a stitch pulled apart at a seam – in today’s linear economy, most textiles flow in just one direction: from raw material, to manufacture, through to the (often alarmingly short) use phase, before being discarded. These discarded clothes end up, for the most part, in landfill or amassing in unthinkable quantities in developing nations, clogging up both their economies and natural environments. A 2022 report by Greenpeace, ‘Poisoned Gifts’, found that only 10 to 30 per cent of clothes donated in the UK are resold in the UK. The vast majority now end up being “donated” (read: dumped, in many cases) overseas. Out of the 11,000 tonnes of clothing donated to Oxfam annually, over half are disposed of or else head abroad to Eastern Europe and Africa. Recycling in its purest form – in which a used product is turned back to virgin material to then be remade into a new product – has, to date, not been possible for textiles. Most textiles collected for recycling are instead used for furniture stuffing, insulation for buildings, or as cleaning rags. “With the development of bacterial cellulose, we’ve demonstrated that this kind of recycling can be done with textiles, the loop can be closed,” Morrow explains. Were this technology to be scaled, it could provide groundbreaking opportunities for textiles to be recycled in ways that have not been possible before.

The 3D printer can create designs with different patterns and thicknesses (image: Textiles Circularity Centre).

Bacterial cellulose, in its most raw form, appears as a translucent, gelatinous sheet. In the Textiles Circularity Centre’s process, raw bacterial cellulose is spun using a technique called “wet spinning”, which produces long, thin strands that can then be woven to form a thin material that has a similar drape to viscose. However, Ribul and Morrow began to realise that using bacterial cellulose to create new textiles would still risk facilitating a culture of consumption. “We started looking at how we can use this technology not to make new textiles, but to repair existing ones,” explains Ribul. Both she and Morrow studied textile design before moving into materials science and circular design, and the pair began experimenting with applying bacterial cellulose onto existing textiles as a means of customisation, reinforcement or repair, using 3D printing technology. “Being a designer allows me to ask what if?” Morrow says. “There’s a curiosity that comes at the intersection of biology and design, and that’s where the innovation sits.” When 3D printed, bacterial cellulose takes the form of sinuous lines, crisscrossing the fabric in patterns of triangles and circles, in different colours and thicknesses. The threads feel raised to the touch, not dissimilar to the embossed texture of embroidery. The materials and construction of the garments are made hyper visible, rather than being hidden away, as is often the case in traditional repair.

The loose thread cut, a new stitch covers the hole left by the old. An enthusiastic, albeit relatively unskilled, stitcher myself, I’ve repaired or altered many of my garments, to varying degrees of success. Clothing manufacture and repair techniques have changed very little for centuries. Repair still relies on hand stitching, embroidery or darning, while even manufacture itself has moved on only marginally since the invention of the sewing machine. Textiles continue to be produced predominantly using methods of knitting or weaving. For the Textiles Circularity Centre, however, the researchers explored how newer technologies could be used to supplement those more traditional ones. “These technologies already exist, but have not yet been used for the production or repair of textiles,” Ribul says. “We’re demonstrating that 3D printing doesn’t just have to be about printing plastic objects but can be used to create new opportunities for repair and customisation.” The motion of the 3D printing head moving back and forth across the fabric in repetitive, parallel movements is not dissimilar to the motion of a hand, pushing thread and needle backwards and forth through a piece of fabric. It is, perhaps, a natural development, in both technique and outcome. It is not a move away from hand repair but, rather, a continuation.

“We’re demonstrating that 3D printing doesn’t just have to be about printing plastic objects, but can be used to create new opportunities for repair and customisation.”

This is still far from a perfect solution. What about garments deemed too cheap to merit repair, for instance, or those that fall victim to rapidly changing trends? The industry is unlikely to address the volume of waste it produces without wider cultural change in how we consume and manage the lifespans of garments. The concept of fast fashion, which accounts for the bulk of waste, is still relatively young; as recently as the early 20th century, most clothes were still made at home or in small workshops. It was only in the 1970s that the exploitative model of fast fashion, at least in the manner we think of it today, became the default. We now need a return to this previous model of clothes ownership, one in which garments are valued, cared for and repaired, rather than discarded after just a few wears. The question, however, is how to bring about this change. “People need to be an integral part of the process of designing and mending their clothing or at least feel connected to or have an understanding of that process,” suggests Morrow. “To challenge our model of consumption, we need to foster closer relationships between people and their garments. We need to make sure that we are using these technologies in a way that aids people to be creative and innovative, rather than taking away their power to do so.”

Clothes are, physically, one of our closest objects: we wear them on our bodies. They are a signifier of our personalities and markers that reflect who we are. But, as wearers, we are often removed from the way they are made and have little understanding of the process, which helps to facilitate the throwaway nature of our current clothing economy. We are not encouraged to think of our garments as valuable, but rather as cheap objects with a short lifespan, to be changed each season. The Textiles Circularity Centre advocates for closer connections between designer, maker and wearer, allowing consumers an increased appreciation of the skill and materials that have gone into each garment they buy.

The Textile Circularity’s exhibition presented a model of a localised system where people are able to work with designers to modify or repair garments (image: Textiles Circularity Centre).

“I had wanted to work in fashion because, to me, fashion is an expression of yourself,” Morrow says. “But studying textile design and working in the industry changed my outlook. Our clothes are so personal in some ways, but totally impersonal in others. So many of the clothes we buy are just mass-produced carbon copies.” This is one of the things I love most about repairing my clothes. I like to think that each embroidered shape does more than merely disguise a hole. It makes them uniquely mine. Of course, not everyone has the time, patience or inclination to repair their clothes, and so, the Centre has modelled a “Social Production Network”, a localised system in which designers and makers engage with consumers in a circular system on the high street. In this model, the ability to recycle and repair clothes using these technologies would happen on a local scale, and consumers would have close links to the people designing, making and repairing their clothes. The possibility to alter or repair garments would be designed into the manufacture process, so that even when buying something new, consumers understand the options they have to customise or mend them, either at the point of purchase or in the future. It would be, in many ways, a return to the model of garment production on a local scale that had been the norm until the mid-20th century, and encourage a closer relationship between maker, wearer and garment.

A patch, a modification. Two pieces of old garments stitched together to form something new. Throughout the four-year project, which ran from 2021 to 2025, the team hosted a series of exhibitions in prime high street locations to engage the public in the research. This was my first introduction to the centre’s work, in an October 2022 in Stratford, London, mere minutes from the paragon of consumerism that is Westfields Shopping Centre. There were samples of bacterial cellulose ranging from the thin, spidery threads of the spun material in its most basic form, to samples of woven and knitted textiles. There was a “Circular Shirt Builder” that allowed visitors to adapt and modify a shirt by changing or removing the collar, pockets, cuffs and hemline, demonstrating how increased involvement in the design process encourages consumers to feel more connected with their clothing. It was here that the role of the designer in this project became apparent. The material innovations form the basis, but it is through the design elements that consumers are engaged and encouraged to consider their garments’ design and manufacture.

the 3D printer is able to create sharp lines and shapes with exact symmetry, precision that would be difficult to achieve by hand (image: Textiles Circularity Centre).

It seems idealistic – unrealistic, even – to picture a high street without the fast fashion giants who have dominated for the last half century, and a move to a system like this would require an enormous amount of investment and infrastructure. The exhibitions allowed the Textiles Circularity Centre’s ideas and innovations to be put to the public, and tested against the expectations of real world consumers. As a research project, commercial feasibility is not necessarily the main aim. Instead, it is about designing and modelling alternative systems. The research focus of the project allowed space to explore and test ideas, without a commercial imperative. There is a beauty in designing solutions, even if those solutions never come to fruition on a large scale.

Think about the clothes in your wardrobe again, the well-loved, the thin with wear. Think about where they came from, where they are going. The textiles industry is still a long way from solving the problem, and this project certainly does not claim to have all the answers. But it has demonstrated a first step on a pathway to a circular fashion future, and how new technologies could be used to offer alternatives to the traditional means of repair that have proliferated for decades. It has shown how vital designers will be in modelling potential solutions for the fashion industry, and then ensuring that the new technologies and materials are adopted. This was a science-based research project, but ultimately, it is a project by and for designers.

Words Rosily Roberts