The Forensic Kit: A redesign

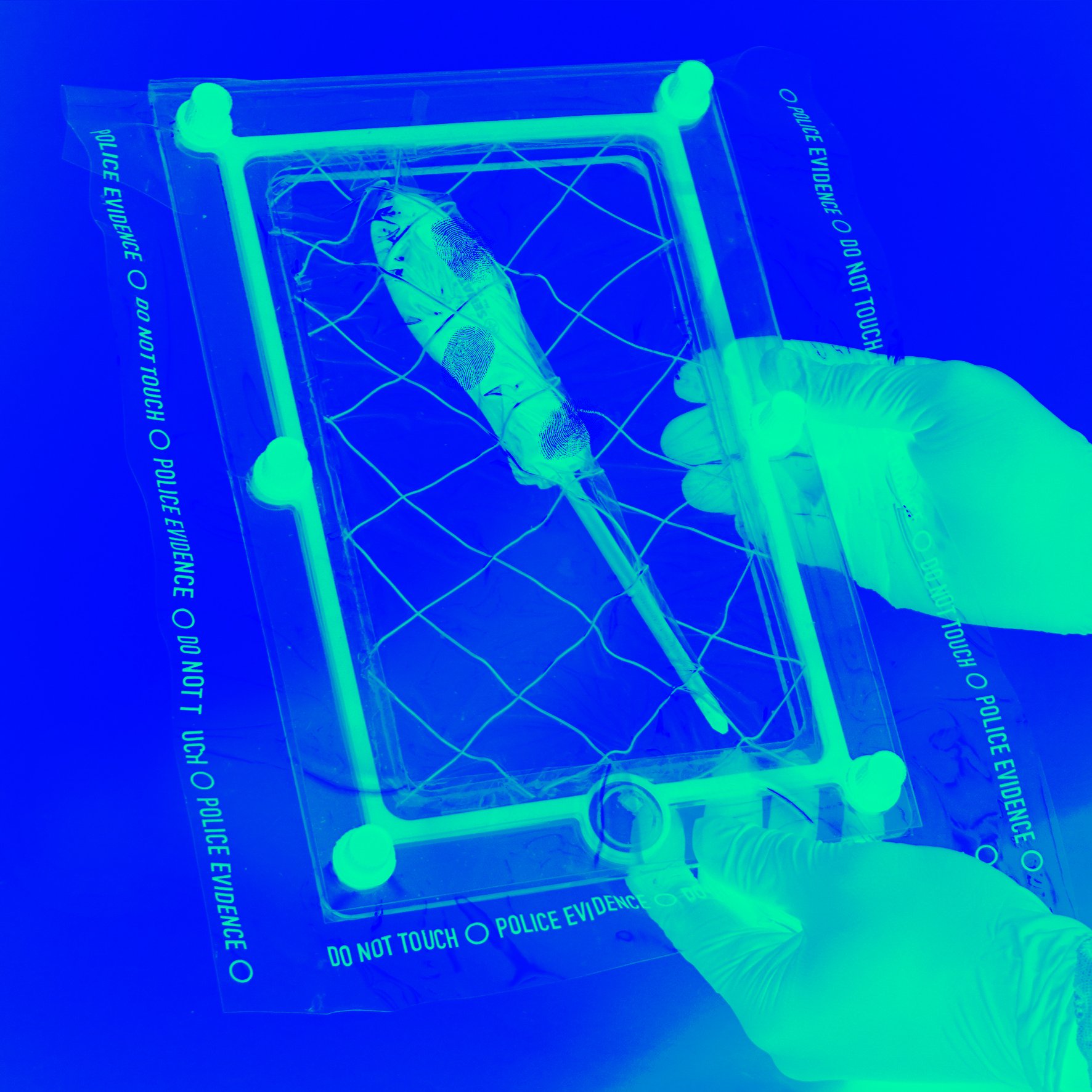

Kate Strudwick has developed a type of forensic packaging that holds items of evidence in position while minimising contamination.

In 1910, the criminologist Edmond Locard set up the first modern forensic laboratory.[1] From his premises in the attic of a Lyonnaise police station, Locard – who had trained in both medicine and law – set about analysing hair, clothing fibres and skin. He wrote treatises on the uses of fingerprints (1914), tobacco ash (1929) and lip prints (1932) as evidence.[2] Locard’s Exchange Principle, which holds that “every contact leaves a trace”, became the core maxim of modern forensics.

In the decades that followed, forensics developed exponentially, quickly becoming a science. In 1984, almost 20 years after Locard’s death, the British geneticist Alec Jeffreys pioneered DNA profiling. Forensic scientists today can marshal a bewildering array of techniques: ballistics, fingerprinting, pathology and entomology, toxicology, DNA analysis, 3D modelling, and more besides.[3] With such an extensive toolbox, its powers can seem miraculous when viewed from afar. TV dramas like Silent Witness (1996-present) and CSI: Crime Scene Investigation (2000-15) have often fuelled this image, to the extent that by 2004 commentators in the US worried about the so-called “CSI effect”, where jurors place so much faith in forensics evidence that it distorts their judgement. “I just met with the conference of Louisiana judges,” recounted one expert interviewed for a 2007 New Yorker report, “and, when I asked if CSI had influenced their juries, every one of them raised their hands.”

Last year, the London-based designer Kate Strudwick discovered how false such glamorised ideas of forensics can be. Strudwick had become interested in forensics through the recent wave of true crime podcasts, led by 2014’s Criminal and Serial, and then spoken to family friends who worked as detectives for London’s Metropolitan Police about Future Crimes, a bestselling explication of cyber-crime from former Interpol adviser and FBI futurist Marc Goodman. “I just started having a conversation with them,” recounts Strudwick, “because as people who work regularly with evidence, I was interested in hearing their perspective.”

Strudwick’s interlocutors painted an entirely different picture from the CSI fantasia: a cash-strapped force reliant on cumbersome and outdated systems, where everything from the security of evidence on the crime scene to the labelling and logging of stored objects was prone to human error. As a student on the Royal College of Art and Imperial College London’s joint MA in Innovation Design Engineering (IDE), she decided to devote her graduation project to finding a better way to proceed.

For.Form is the result of extended research, experimentation and testing with potential users. After identifying the numerous flaws in the present processes, Strudwick set about designing items that would allow evidence to be secured on scene, stored and logged. The outcomes – a mouldable wrapping material; a kit centred on a piece of that material to protect and package evidence; a proposed system of storage – may, if put into production, mitigate many of the problems facing forensics officers today.

Strudwick began her project with extensive contextual research. She visited a police station, the Old Bailey and a Home Office violent crime prevention workshop, and attended the annual Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851 lecture by Susanna Challinger, a researcher into the applications of Kelvin probe force microscopy in examining fingerprints. A particularly eye-opening experience was a visit to the Forensics Europe Expo at Kensington Olympia, the only European exhibition covering every aspect of forensic science. “I felt like a spy,” she recalls. “There were a lot of military products like armour, but there was also some really advanced technology for detection.”

Among other things, Strudwick saw devices utilising Lidar measurements to create 3D simulations of crime scenes through laser light. The exhibition also included 3D mapping programs and technology for extracting deleted data from phones and apps. Other recent innovations with the potential to make forensics more accurate include the portable Lab-on-a-Chip, which could allow forensic analysis to be carried out on the spot by police rather than sent to labs, and the miniPCR, which rapidly creates billions of copies of a DNA sample in order to study it.[4] However, it is unlikely that these devices will be used by police forces anytime soon. “There is a gap,” explains Strudwick, “between the sort of stuff being produced and the equipment the police can actually use. There’s budgeting and a lot of tests they have to go through to ensure that something answers every question it needs to.”

A decade of Conservative-led government in the UK has made budgeting increasingly tight. There has been an overall 19 per cent slash in police funding over the course of the decade, with around 45,000 staff lost across the country. “Crime scene management,” wrote Val McDermid in her 2014 book Forensics: The Anatomy of Crime, “has become the front line in the investigation of murder”. Nonetheless, according to Strudwick’s research, since 2010 the number of crime scene managers (CSMs) has halved, challenging the ability of those who remain to be on the scene during the vital “golden hour”, the early stages of the investigation in which the greatest police resources are deployed. One of Theresa May’s earliest edicts as home secretary was to close the government-funded Forensic Science Service, forcing police to rely instead on private-sector contracts. Due to the expense, as Strudwick learned, only five pieces of evidence can now be submitted for analysis, forcing CSMs to make quick decisions on the most pertinent gathered objects. The effects of this are reflected in statistics: Home Office figures show that, in the twelve months running up to March 2019, only 7.8 per cent of recorded offences led to a summons or charge, compared to 9.1 per cent in the previous year. A 2018 BBC News report, meanwhile, identified a 70 per cent rise in England and Wales of cases that have collapsed due to a failure to provide evidence.

Through her conversations with members of the Met Police, Strudwick identified problems at three stages of the present system, beginning with protection of the crime scene. A rambling process, whereby first response officers, then detectives, then finally the protective-clothing clad CSMs arrive, can see evidence exposed to natural contaminants. This is especially true outdoors, where crime scenes can span extensive areas. Items used to cover evidence can take further time to arrive, and require cleaning before use. “Chances are,” said one of Strudwick’s interviewees, “you’ll ask for a tent [to cover part of the scene], and so and so has the key to get it and they’re busy, or they’re not working, or you get it and it hasn’t been cleaned since the last scene. We just end up using bin lids or crates, anything we can find really.” As the technologies available to forensic scientists become more sensitive, these deficiencies in police processes become more apparent and the margin of error wider.

Secondly, Strudwick found issues with packaging evidence once it has been removed from the scene. Forces currently deploy a legion of different sized bags, in paper and plastic, with little consistency. “There are,” revealed another of Strudwick’s respondents, “about 43 different ways of packaging a knife or a bottle.” These bags are not sterilised before use, allowing for possible contamination. Plastic bags are not breathable, so wet evidence degrades, while paper bags are opaque, meaning that evidence cannot be seen without the bag being reopened. Both types suffer from weak seals.

In Britain, pieces of evidence may be retained for several years after a conviction, to allow for appeals. Strudwick’s third insight concerns the problems of processing and storing these items, which are often inconsistently labelled. The station Strudwick visited had a significant backlog of objects from different cases, preventing them from being quickly stored. And evidence can change over time. “There was a case in Italy,” explains Strudwick, “where the blood dried and became powder.” While in storage, this powder gradually spread from its original location on the shirt, making it hard to use as evidence. The loose structure of a bag means that even fingermarks on the evidence within can move while being transported. Once evidence is stowed, in large boxes stuffed with rows of bags, their handwritten labelling can lead to further errors. “As there’s not a huge amount of investment into technology and future-proofing,” says Strudwick, “they’re struggling with certain things at the moment.”

Perceiving these problem areas, Strudwick set about designing a solution that could improve all three. The police’s stringent budget offered an unusual advantage for a student seeking an implementable product. “It’s interesting working on a student budget,” she says. “You’re forced to be quite cheap with your materials, which is exactly what the police have to be as well.”

While her initial sketches contained an imaginative range of ideas – early inspirations included silly string, origami, sticky back plastic and Monsters, Inc.-style vacuum pods – she narrowed down the possibilities through a series of “what if” questions that suggested a potential form. “What if a mould could be made of the evidence on site to create a unique protective shell?” ran the first. She then investigated whether a membrane could be created to surround and gather information; whether the current plastic bags could be augmented to hold the evidence in place; whether the bags could be inflated in different ways to trap and protect; and finally, whether a membrane could take and preserve the shape of the evidence without requiring the use of any additional equipment. At each stage, she eliminated unsuccessful techniques. Using her home as a makeshift crime scene, she marked dummy pieces of evidence with her fingerprints. After the evidence was contained by her materials, she rubbed iron filings over the protected samples to test whether her fingerprints could be retrieved.

“I set down what the parameters had to be,” explains Strudwick. “What was necessary and what was ideal. I started playing around with different materials. It was quite rigorous and logical – not the most creative way of working.” Seeking materials that would be transparent, elastic, breathable, waterproof and able to morph while maintaining the shape of the captured object so that it could be removed, then repackaged in the same position, she worked methodically through more than 20 pre-existing substances: homemade organics such as agar and gelatine, alginate, thermoplastics, plaster, latex and parafilm. Strudwick consulted Imperial’s Future Materials research group for advice, while ordering small plastic samples from manufacturers, Amazon and artists’ supply shops. It eventually emerged that no single material met all of her objectives, so she began investigating composites.[5]

Strudwick invited the two officers she initially interviewed to test her work so far and assess what forms worked best and most intuitively. The prototype that emerged from her findings centred on a weighted, transparent, mesh-like sheet that can be placed atop potential items of evidence. It then forms a dome around them, weighted down by a sandbag-like system. The skirted dome can be collapsed when crime scene officers arrive and turned into packaging without being directly touched by a human hand. A foldable, reusable plastic frame resembling a food clip can be used to seal the material. Finally, Strudwick proposed magnetic security cards to store the packages tightly and consistently, adding RFID chips[6] that could allow each piece of evidence to be tracked automatically.

For.Form may prove the initial phase of a lengthy process of prototyping, testing and refinement. Although further development is on hold – Strudwick has recently started working at Google’s Creative Lab – she has begun discussions with a leading manufacturer of police equipment to develop her ideas further. “If they decide they want to use it,” she says, “and it makes a small improvement to an incredibly complicated system, that would be great. To know that you’ve done something to help – I think that’s what design is all about.” While high-tech developments continue to push forensics into the orbit of science fiction, For.Form may elevate the work on the ground.

1 Forensics does of course have a long and diverting prehistory, stretching back at least as far as the Chinese bureaucrat Song Ci’s Washing Away of Wrongs, written in 1247.

2 In this, he was building on the work of fictional detective Sherlock Holmes, who in 1887’s A Study in Scarlet, was noted to have examined cigar butts. And indeed, Locard became known as the “Sherlock Holmes of France.”

3 It also has applications outside criminal cases, as the human rights research group Forensic Architecture’s work amply demonstrates.

4 DNA advances are particularly astonishing. In 2018, for instance, the serial rapist and murderer known as the Golden State Killer was captured for crimes committed between 1974 and 1986 after detectives uploaded a genetic profile from a rape kit to a genomics database, constructed a virtual family tree, narrowed down potential matches, and then collected DNA samples from the suspect’s car handle and a tissue in his garbage can. “Without this technique,” said investigator Paul Holes, “I’m not sure we would have solved this case anytime soon.

5 I will have to leave the reader to solve the case: Strudwick is under an NDA regarding For. Form’s material components.

6 Radio frequency identification tags (RFID) use radio waves to consistently monitor an object’s status or location. They are already used to track pets, cars, cattle and whether an aeroplane seat has a life jacket beneath it. Plans are afoot to use them for retail, so that at the check-out all the products in your basket would immediately be scanned and charged to your bank account, incidentally alerting the retailer to exactly what you have bought.

Words Joe Lloyd

This article was originally published in Disegno #26. To buy the issue, or subscribe to the journal, please visit the online shop.