A Floral Algorithm

“I want to look more broadly at issues of nature, ecology, biodiversity and loss,” the artist Daisy Alexandra Ginsberg told Disegno in issue #24 of the journal. “We’re fucking up this planet and I’m not hopeful that we will stop.”

Ginsberg had recently completed a PhD by practice, ‘Better: Navigating Imaginaries in Design and Synthetic Biology to Question “Better”’, as well as a series of projects that revolved around interconnected questions. What does it mean to suggest that design can make things better? Better for whom? What can art and design actually offer in an age of climate collapse? And how might we think about “different ways that the world can go” in order to think through our own present values and priorities. “I’m not depressed!” Ginsberg assured Disegno’s interviewer, but she nevertheless acknowledged an emergent strain of melancholia within her work, which she characterised as having to come to “look more broadly at issues of nature, ecology, biodiversity and loss.”

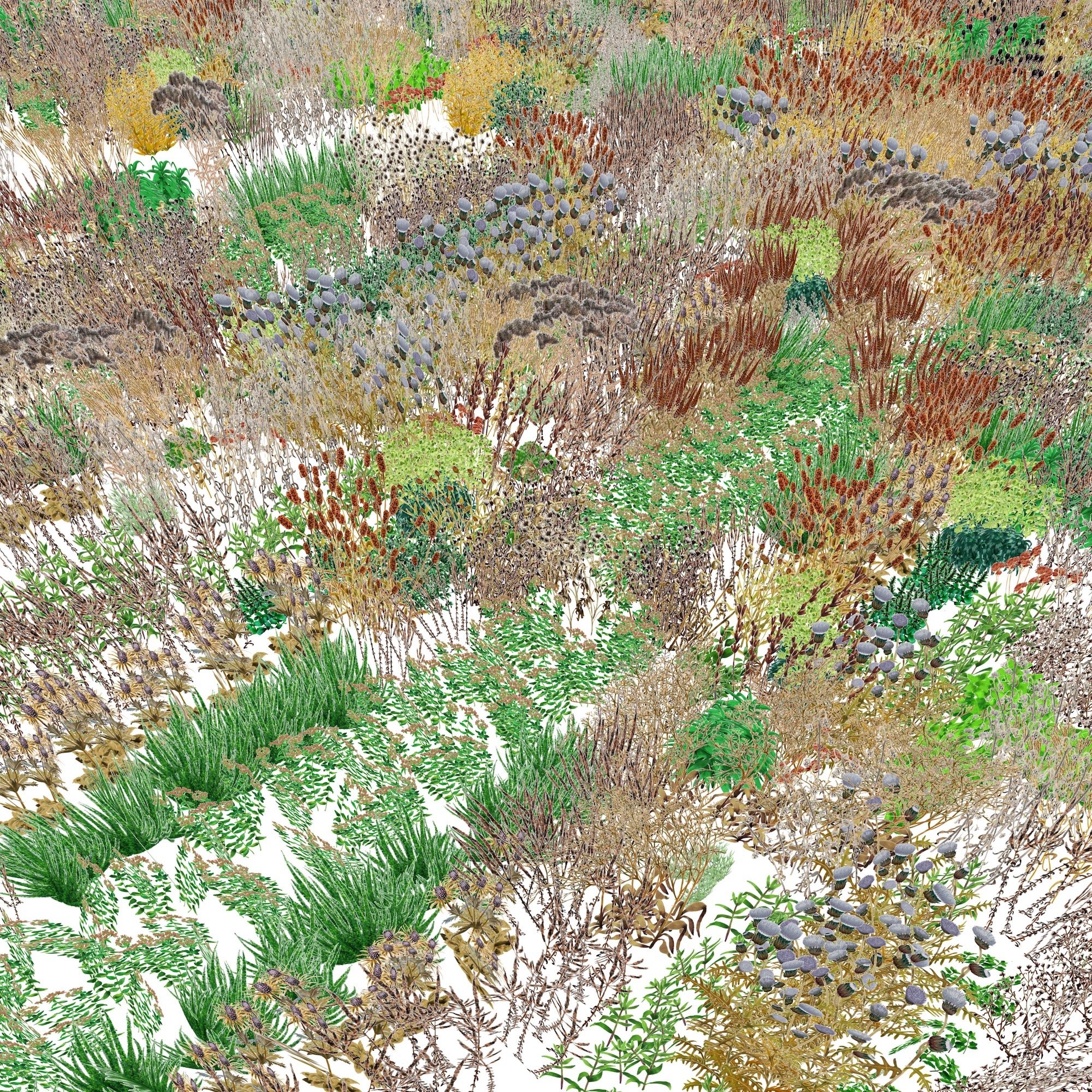

Pollinator Pathmaker, Ginsberg’s most recent work, sees the designer embark upon a more obviously upbeat path. Commissioned by Cornwall’s Eden Project, Pollinator Pathmaker is an online platform that allows users to create gardens designed for pollinators, rather than humans. Users input a series of values (the size and rough shape of the land they wish to plant; soil type and PH; light levels; and a handful of other preferences), which are then assessed by an algorithm. Working through a list of suitable plants, the algorithm then generates a garden designed to specifically cater to the tastes and needs of as many pollinator species as possible (such as bees, hoverflies, butterflies, moths, wasps and beetles). The creation springs into life through a digital model rendered in watercolours painted by Ginsberg herself, with the model revealing how the garden will change across the seasons, and providing different viewing options to show how it may be perceived by pollinators.

“I want to look more broadly at issues of nature, ecology, biodiversity and loss. We’re fucking up this planet and I’m not hopeful that we will stop.”

While Ginsberg’s past work has been restricted to galleries and their ilk, Pollinator Pathway is intended to resonate more widely. Users are able to print off instructions to physically plant the gardens they create using the platform, while a flagship 55m-long pollinator garden has already been planted by Ginsberg at Eden. Further gardens are to be planted in 2022 at the Serpentine Galleries in London and the Light Art Space in Berlin.

Pollinator Pathmaker, then, sees Ginsberg’s work take on a more explicit public and participatory edge, but it raises the same kinds of questions that have preoccupied her other recent works. A garden is typically a space in which nature is sculpted to suit human aesthetic tastes, but could the typology be reframed to meet the needs of other species and might our urge to “better” the world be extended to account for ideas other than its utility to humans? To find out more, Disegno spoke to Ginsberg over Zoom about the project.

Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg, photographed at the Eden Project planting a Pollinator Pathmaker garden (image: Steven Tanner).

Disegno The project is reminiscent of some of your recent work such as The Wilding of Mars, as well as your PhD and its exploration of the notion of “better” in design – better for whom? Extending those ideas to non-human pollinators is an interesting continuation. So how did Pollinator Pathmaker come about?

Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg I'm pleased that you spotted a thread! The four works I completed after the PhD – Resurrecting the Sublime, The Wilding of Mars, The Substitute, and Machine Auguries – form a series, putting into practice ideas I set up in my PhD, but didn’t get to test. Pollinator Pathmaker learns from them and is the next step. Two questions that came up for me around those earlier pieces were “What does it mean to put this kind of work with this kind of subject matter – environmental crisis caused by certain humans – in a gallery?” and “What am I asking the gallery audience to do?” You may be emotionally affected by them, but then what? And does that matter? Is a moment of emotional transformation enough or should there be a call to action? Those four works use technology to bring attention to the paradox of our obsession with innovation; the idea that the new is somehow better than preserving what already exists. In different ways, they all try to make the viewer the subject of the work: The Substitute is a digital rhinoceros, that looks you in the eye–

Disegno Which is a very visceral experience.

Daisy –but can we then design from that perspective? How do we step into that perspective and use it to see the world through the rhino’s eyes? Instead of highlighting how we use technology to better the world for ourselves, can we use it the other way around? Can we use technology to buffer the natural world from us and (in this case, with Pollinator Pathmaker) our aesthetic tastes, and instead focus on the tastes of other organisms and their interactions? What was fundamental with Pollinator Pathmaker was this existential question of what is it to make ecological artwork and put it in a gallery. When I was shortlisted for the Eden Project commission, it was really inspiring to learn about their principles. Eden wants their audience to feel a sense of awe and connection with the natural world and a sense of jeopardy, but also to inspire hope and agency. And it was that word “agency” that really resonated with the questions that I was facing.

The Pollinator Pathmaker website (image: courtesy of Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg).

Disegno In what way?

Daisy When The Substitute was shown at the Royal Academy as part of the Eco-Visionaries show, there was a review in The Times by Rachel Campbell-Johnston which picked it out and said something along the lines of “Ginsberg has no answers”. I loved that. I’m often told that I only have questions, but why are artists and designers expected to have solutions to the climate crisis? My PhD research challenged the assumption that design can “make the world better”, so why should artists and designers in particular have answers? Pollinator Pathmaker is not about finding a solution, but it is exploring the idea of agency. I’m trying to deal with my own panic. What on earth am I doing making pretty things that sit in museums?! I love doing that, and I'm not going to stop, but what else can I do? Can I usefully use my skills in other ways too?

“What does it mean to put this kind of work with this kind of subject matter – environmental crisis caused by certain humans – in a gallery and what am I asking the gallery audience to do?”

Disegno How do you feel about exhibiting work in a more neutral forum? Galleries and museums can clearly be public spaces, but people are often in a particular mindset when they go into them: they’re perhaps expecting to see critical artworks, whereas an audience coming across a garden or an online platform is not necessarily primed for thinking about those as a means of challenging how we think about design or who we're designing for. With Pollinator Pathmaker, you don’t have a gallery or museum doing some of that initial work in setting the tone for you.

Daisy Well, you say that people in museums are already in that kind of critical mindset, but lots of people might go to a museum for a date or something – they’re good places for lots of different things. But I agree that these spaces are places of reflection and so there all sorts of questions about how you design the communication around a project like Pollinator Pathmaker, which isn’t in a gallery, so that it makes sense to people. For the general public arriving at pollinator.art, how do you begin to explain that a garden is not just for us, but that this is an artwork for pollinators; that you can use an algorithm to create and download a garden design for free, which you can plant as your own edition, and join in to help create the world’s largest climate positive artwork. That’s a lot of new stuff to communicate and design for.

A concept image for the project created by Ginsberg (image: courtesy of Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg).

Disegno So how did you approach tackling that?

Daisy The first assumption we made is that people are going to end up on the website already having at least some idea of what it is, but we want to get them into the experience as quickly as possible. We tried to simplify the experience as much as possible as we developed the site with The Workers. But it’s additionally challenging because there are so many different audiences that I want to reach. It needs to not be scary for the kind of person who probably has a garden, but who may be less interested in digital art or less computer-savvy, as well as for the kind of person who is interested in digital art, but has never gardened and may not have a garden. It's about getting through those first few stages of explanation such that you arrive at the algorithmically generated garden itself, this moment of excitement and wonder, and then you can start to understand it.

Disegno The website is very intuitive to use, but it’s interesting because, typically, these platforms that let you design something – be it a character in a video game or a brand’s AR system for trying out products in a space – are very centred on you as the individual creating something exactly for you. The experience is presented such that you can tailor something to suit you perfectly. But this project is explicitly about not designing for you.

Verbascum nigrum or dark mullein: one of the plants included within the initial Pollinator Pathmaker species list (image: courtesy of Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg).

Daisy For more experienced gardeners, there's a real challenge in that. In our user research, I spoke to volunteers at a community garden, who are all very experienced gardeners, and who got frustrated by the idea. They were like, “Well, I have certain plants that I want to use. Can't I just tell the programme which plants I have?” The loss of control may be fun for a beginner because it gives you a confidence to design that you otherwise might not have, but for the more experienced gardener there is this sense of “But I know more.” What's conceptually interesting about that challenge, however, is that it presents this fundamental question of what is a garden and who is it for? That's a real mind shift. Why do you want to use the plants that you normally choose? Well, you may have spare cuttings or something, but a lot of it ultimately comes down to the fact that you probably like the way they look. But those plants may not be the best for pollinators. User testing was great fun because we had all these conversations, giving us understanding of what the work was doing. The tagline we ended up with – “If pollinators designed gardens, what would humans see? – sums up that feeling of this not being for you. “It’s not for us, it’s for the bees”, as one of our testers explained to another.

“What’s conceptually interesting about the challenge is that it presents this fundamental question of what is a garden and who is it for? That’s a real mind shift. ”

Disegno So what factors does the algorithm taking into consideration, because figuring out what pollinators actually want must be the central challenge.

Daisy An algorithm can never remove human bias, but I wanted to buffer design decisions. The algorithm was developed by Przemek Witaszczyk, who kept saying, “Daisy, what is the top problem to solve?” because I had this whole list of things that I wanted the algorithm to do. We figured out that the fundamental idea was to make a garden that's empathetic to other species. Even if you were to design a pollinator friendly garden, you would still arrange the plants according to how you want them to look. You’re still making choices. You may prefer one foxglove to another, and you’re also making decisions about which pollinators you’re designing for. Even if you’re making an empathetic garden, you still have to define what empathy means. I had to make a codeable choice and I ultimately decided that empathy in this context should mean maximising diversity – optimising for the maximum number of pollinator species possible in every solution that the algorithm makes. Well, there’s lots of ways to skin a cat and part of the problem is that nature is really complex because co-evolution is an amazing thing. For example, it had never occurred to me before why flowers bloom at different times of the year – because that's when their pollinators emerge! The flowers and their pollinators come out at the same time and the flowers are a particular colour because they’re pollinated by specific pollinators, who see different colours.

Disegno It starts to become very complicated.

Horticulture apprentices and students assist with the planting of the Pollinator Pathmaker garden at the Eden Project (image: Steve Tanner, courtesy of the Eden Project).

Daisy Right. Every parameter is interlinked. The next task was to construct a plant palette – a database of plants that are good for pollinators - for our starting region of Northern Europe, which has 154 plants in it. We know each plant’s pollinators, when it flowers, its soil and climatic conditions, and more. Then there are different “architectural” groups of plants to ensure variation. So, there is an element of human aesthetic choice, but at the same time plant architecture also relates to what pollinates a plant. Small primroses will come out earlier, while taller plants that would otherwise shadow the primroses flourish later. As one of our advisors Marc Carlton put it beautifully, you need flowers of different sizes in a garden, with different shaped flowers for different shaped mouthparts. All these factors overlap and the algorithm uses them to compute a planting design that serves the maximum pollinator species possible.

Disegno But the user does have some influence on how the algorithm achieves that, right?

Daisy If it was less nuanced, it would just choose one flower that serves everyone and suggest a field of daisies or something, but then you don’t have blooming across seasons, for example, so it’s not the best solution. The algorithm solves the problem in multiple ways. The patterning itself is divided into different scales. There’s the macro scale – pollinators coming into and across this big, bright field – which the human user can play with its boldness. If you choose to use more or fewer species, you’re adjusting how many plants you’re picking from the database, which is interconnected to the intricacy or boldness of the pattern. If you choose a bolder pattern, it will choose more plants that suit many pollinators, while intricacy is going to give you a more specialised species. The next field of scale, the mid scale, deals with how pollinators forage. Some, like bees, visit thousands of flowers in a day, remembering their locations, and calculating the shortest paths between them. We cater to them through a slider which offers you a choice between more paths, or more patches. Paths will select a subset of plants that suit bees and path-following species, and add more of those into the garden, whereas more patches will use a subset of plants in blobs for more random foragers, like beetles. Whatever solution it comes up with, it will still have calculated it to serve the maximum number of species.

“Even if you’re making an empathetic garden, you still have to define what empathy means. ”

Disegno Was it a difficult decision to include things like that which give people a degree of control? Because a key feature of the project is the importance of surrendering choice and thinking about things from a different perspective.

Daisy Well, although you do have choices to make, they're both for you and not for you. In a way, it's trying to make you feel a sense of responsibility: if I tweak this parameter, what will the effect be? There's also something in providing choice in terms of offering people a route into this. If it just gave you a garden once you’d inputted your environmental conditions, then you perhaps wouldn’t have the same understanding of or compassion for what’s going on. The options are a way to invite thinking about these issues. We have user inputted values, and we invite people to engage with them and their implications by calling them something weird like “paths or patches”. They’re making choices, but they're choices they wouldn’t normally make and which give them pause for thought. That’s why put these parameters into the oddly-named “empathy toolbox”

A preparatory sketch for the project (image: Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg).

Disegno The gardens have been executed as watercolours–

Daisy iPad watercolours.

Disegno They look beautiful, but I was curious as to why you adopted that art style. For a project that is about putting forward an idea of gardens that differs sharply from the familiar sense of them being principally for human enjoyment, it’s the most traditionally “pretty” aesthetic you’ve worked with.

Daisy There are three reasons. Firstly, I don't want to not make the kind of work that I’m doing, but I wanted to not feel like the project manager or art director for once! It was a conscious decision that I really wanted to draw, which I basically haven’t done since A Levels. I may not have 3D modelling skills, but I can paint.

Disegno That’s interesting, because so many times people speak about the figure of the designer as a connector and someone who links everyone together. It’s quite a romanticised framing that is often wonderful – and that way of working does enable some incredible things – but it also sounds much less glamorous and enchanting as a position when you describe it as “project management”.

(Image: Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg).

Daisy Right. I’ve been making big complex projects and you can see that when you look at the credits list, so for Pollinator Pathmaker I was determined to do this myself. But the second reason for the aesthetic is that it was really important to me that it not be “scary” as an algorithmic artwork, given the audiences I want it to appeal to. I’ve previously used aesthetics as a way of gently prodding certain tropes that we’re used to seeing in terms of a colonial representation of nature – which is something I looked at in The Wilding of Mars, for instance, with the sublime landscape. Pollinator Pathmaker, however, uses the softer language of watercolours, rather than CGI, to make the experience of moving through an algorithmically designed garden more pleasurable and less intimidating. But it also brings a kind of synthetic newness to it. It's garish yet plays with the language of botanical illustration.

Disegno And the third reason?

Daisy When the pandemic hit, I had to essentially close my studio. When I was developing the pitch, I didn’t have much option but to draw in coloured pencils. But that necessity gave an interesting juxtaposition between the naïveté of the initial sketches and the sophistication of the final algorithm – which ended up being the pleasure of the aesthetic. It’s got a weirdness insofar as the illustrations are flat, so when you zoom around the garden you get a visual glitchiness. It's not perfect – plants become transparent, or go strange and bendy. It reveals the computation behind it.

Disegno We’ve spoken a lot about the digital aspects of the work, but it’s important to note that this project is also resulting in actual gardens – you can go to Eden and walk around the one you designed, and users are encouraged to plant their own. That must be satisfying for you.

“When you zoom around the garden you get a visual glitchiness. It’s not perfect – plants become transparent, or go strange and bendy. It reveals the computation behind it.”

Daisy There are so many things that I'm experimenting with or excited to learn about with this. I mean, the Eden garden is 55sqm and 7,000 plants. That’s exciting, particularly because in designing this garden, I didn't really know what it’s going to look like, which is thrilling. I'm not a garden designer – I can't just visualise it from a plant list. When we designed the scheme for Eden, we generated hundreds of options and then narrowed it down to one, but we planted it without really knowing what it was going to look like, because the visualisation tool wasn’t finished – I hadn't painted all of the flowers yet! Even with the tool, there is still an uncertainty about a garden: it’s going to change, it's going to do its own thing like one plant taking over. There’s something conceptually interesting that insects are going to come and steal bits of the artwork, give bits to it, or that new bits will grow.

Disegno And new gardens will emerge as people engage with the online platform.

Daisy You can plant a whole artwork from seed. You can create the design online, then go off to buy seeds online, and have them sent in the post. That's interesting in terms of distributed manufacturing and fabrication. I’d been in conversation with Google Arts & Culture [a partner on Pollinator Pathmaker, ed.] for a while about doing an online experiment, but I'd struggled with what an online experiment could be. The Google Arts & Culture digital experiments are fascinating, but I wondered whether they could also transition into the physical world, as something you could print or take away. What we've ended up with is something you can not only print out, but which you can subsequently plant in the ground – it's really nice to think about those online experiments as tools to make physical things. It’s anti-NFT In a way,

Disegno I’m very relieved to hear you say that, because it would have been incredibly easy – and of the moment – for the algorithm to produce NFT gardens.

Planting for the Pollinator Pathmaker garden at the Eden Project (image: Steve Tanner, courtesy of the Eden Project).

Daisy People have asked that: “Can you do NFTs?” No! If it's for private use, you can download your instructions for free, and then plant it at your own cost and risk. That's part of this ethos of empathy and generosity, which everyone who's been involved with this has been really excited about. I’m the caretaker of my DIY edition of the artwork, and I'll enjoy looking at it and watching the bugs that appear, but the artwork isn't really for me: I’m looking after it for other species. The idea is that there should be a generosity throughout the model: when new international editions of Pollinator Pathmaker are commissioned for new regions, the research that goes into developing a new database of plants is given back to the website, free for anyone to use. I’m very aware that it’s an incredible privilege to have a garden at home; what we really want to work on next is the community element. The Pathmaker tool is for private use, but there’s a form on the website to get permission to plant gardens in a community spaces or in schools, which I really want to happen. The challenge is finding a mechanism to help people do this. There's an inbuilt privilege to gardens and so to Pollinator Pathmaker DIY editions, but we don’t want this to just be about private gardens. We need to find a way to make a network of big and small, private and public and shared pollinator gardens?

Disegno You could see it being useful in an educational context. It could provide a route into thinking about the way in which we treat the natural environment.

Daisy It’s very challenging to talk about this from a place of privilege and say, “Well, what is a garden? Who's it for? Well it's not for people, it's for insects.” Especially given what we've all been through with the pandemic, and the privilege that access to gardens represented during this period. The gardens on the website are built on 50cm pixels, which we had to set as a minimum to include fully grown plants. To get an interesting pattern, you do need a bigger plot, but we also give advice on how to scale the pattern down to flowerpots, for instance. Actually, none of the specificities of the garden really matter. What matters more is thinking about what we plant, where we plant it, who it's for, and why that matters. We want to get people engaged with thinking about how we do better for other species.