Enter the Matrix

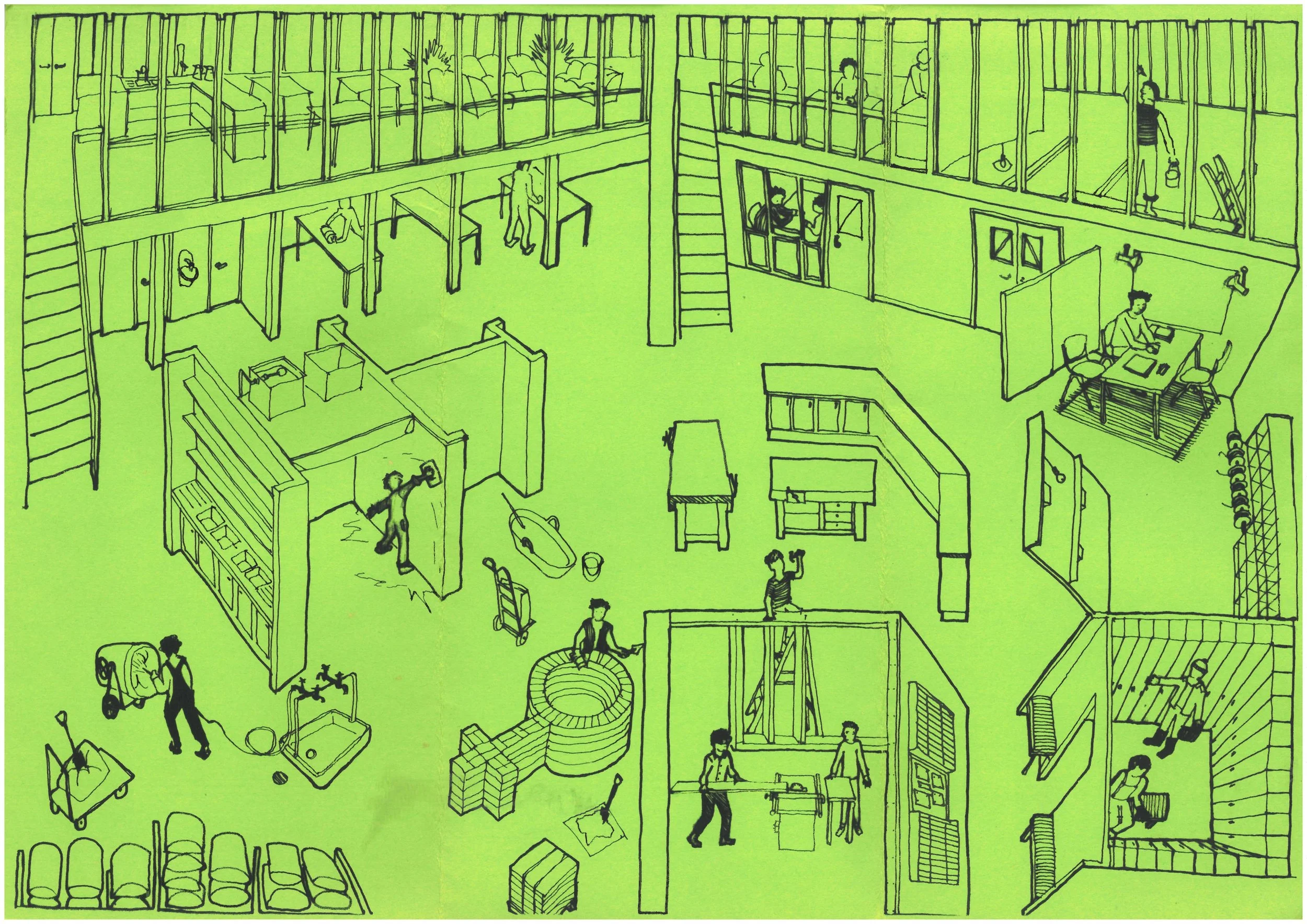

A promotional postcard for Matrix (image: Matrix Open Feminist Architecture Archive).

The contribution of women to design practice and history has largely been ignored. Full stop. This has been an accepted truth for decades, but only recently has it materialised in concrete efforts to rectify this erasure.

Yet while we are finally coming to appreciate the full scale of the contribution of practitioners such as weaver Gunta Stölzl or architect Lina Bo Bardi, more questions have emerged. Are our historiographic tools out of date? Is the lens through which we view the history of design too myopic? If we dump existing definitions and cast a broader net, could we start to find role models who may guide us toward a more socially and ecologically sustainable design practice? We have become accustomed to attributing the authorship of works to individual designers, as well as recognising their innovation through the material or formal aspects of their work. But the large-scale teamwork necessary to bring a project to fruition, or the participatory processes that can make, for example, a community hall more innovative than a developer-funded commercial office building are hard to show in portraits and pictures. They have, therefore, slipped under the radar of recognition.

In this vein, many narratives of design and architectural history have overlooked – or at the very least under-recognised – the work of the Matrix Feminist Design Co-Operative, a London-based architectural collective that was founded out of a left-wing feminist design movement active in the late 1970s. Despite this lack of recognition, however, it is impossible to underestimate Matrix’s potential for providing a model of future practice in multiple ways.

The first point to note is that Matrix ran their practice as a collective, not as a hierarchical structure with a domineering “genius” as its face. As companies and design studios alike grapple with finding ways to work more collaboratively, they need look no further than Matrix to show them how. Secondly, Matrix intuitively developed an understanding of intersectionality decades before a more mainstream recognition that marginalisation and discrimination usually happen on more levels than just one. Matrix was particularly attuned to working with communities that were marginalised in multiple ways, such as single mothers from migrant backgrounds. Thirdly, at a time when both design education and practice were still dominated by the one-size-fits-all doctrines of standards and universal solutions of post-war modernism, Matrix recognised that the act of designing is neither passive nor neutral. As the architecture writer Jon Astbury identified in his opening text to How We Live Now, a 2021 exhibition on Matrix that was staged at the Barbican, Matrix were aware that “consciously or otherwise, designers work in accordance with a set of ideas about how society operates, and who or what is valued.”

“Urban Obstacle Courses”, a photo of Ann Thorne and her children.

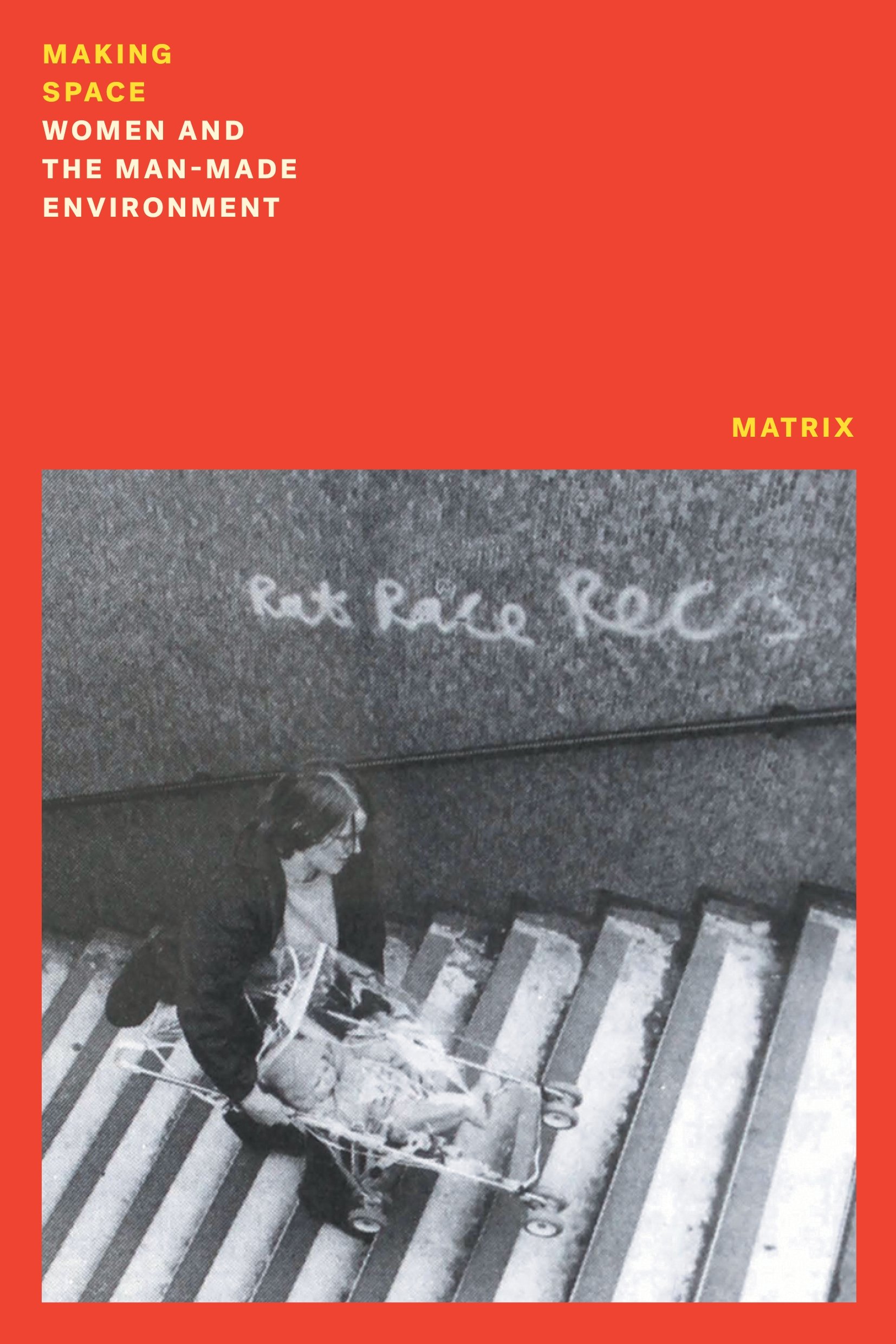

Matrix explicitly addressed the relationship between gender and the built environment. Combining both a practice of research and a practice of building, they formed a group to investigate and reveal the deficits of cities produced by male-dominated urban planning. Making Space: Women and the Man-Made Environment, their collaboratively written treatise, was published in 1984 (today, a much sought-after original copy would likely set you back hundreds of pounds). Meanwhile, at the practical level, Matrix designed social housing and women’s shelters, and launched a number of initiatives aimed at making the architectural profession more accessible to women.

Although Matrix dissolved in the 1990s – around the same time that the ecosystem of housing and property in which they operated was fundamentally changed by the UK’s Conservative government – interest in the collectives’ groundbreaking work has been rekindled in recent years. Making Space was republished by Verso Books in March 2022, accompanied by a new foreword from researchers and architecture historians Katie Lloyd Thomas and Karen Burns. Elsewhere, some of Matrix’s original members have been working to create an archive to document and preserve the collective’s work: How We Live Now, for example, was co-curated by Jos Boys, co-author of Making Space. All of this illustrates that the questions Matrix were grappling with in their work have lost none of their relevance for today’s architectural practice. Who are our buildings and shared spaces designed for? Who is excluded from this designed environment and what effect does that have on the communities who live there?

In the roundtable that follows I spoke with Boys, Ann de Graft-Johnson and Mo Hildenbrand, all of whom were original members of Matrix. Together, we aimed to make a contribution towards keeping the legacy of the collective alive.

A photo of the central courtyard of the Jagonari Asian Women’s Centre.

Viviane Stappmanns Matrix was active from 1981 to 1994, and you were an all-female workers cooperative with a non-hierarchical structure. You worked on state-funded social building projects, including women’s centres and refuges, facilities for women and children, construction training workshops, and lesbian and gay housing projects. There is so much in that description. I would like to deconstruct that a little bit and go back right to the beginning and ask you: how did Matrix actually start?

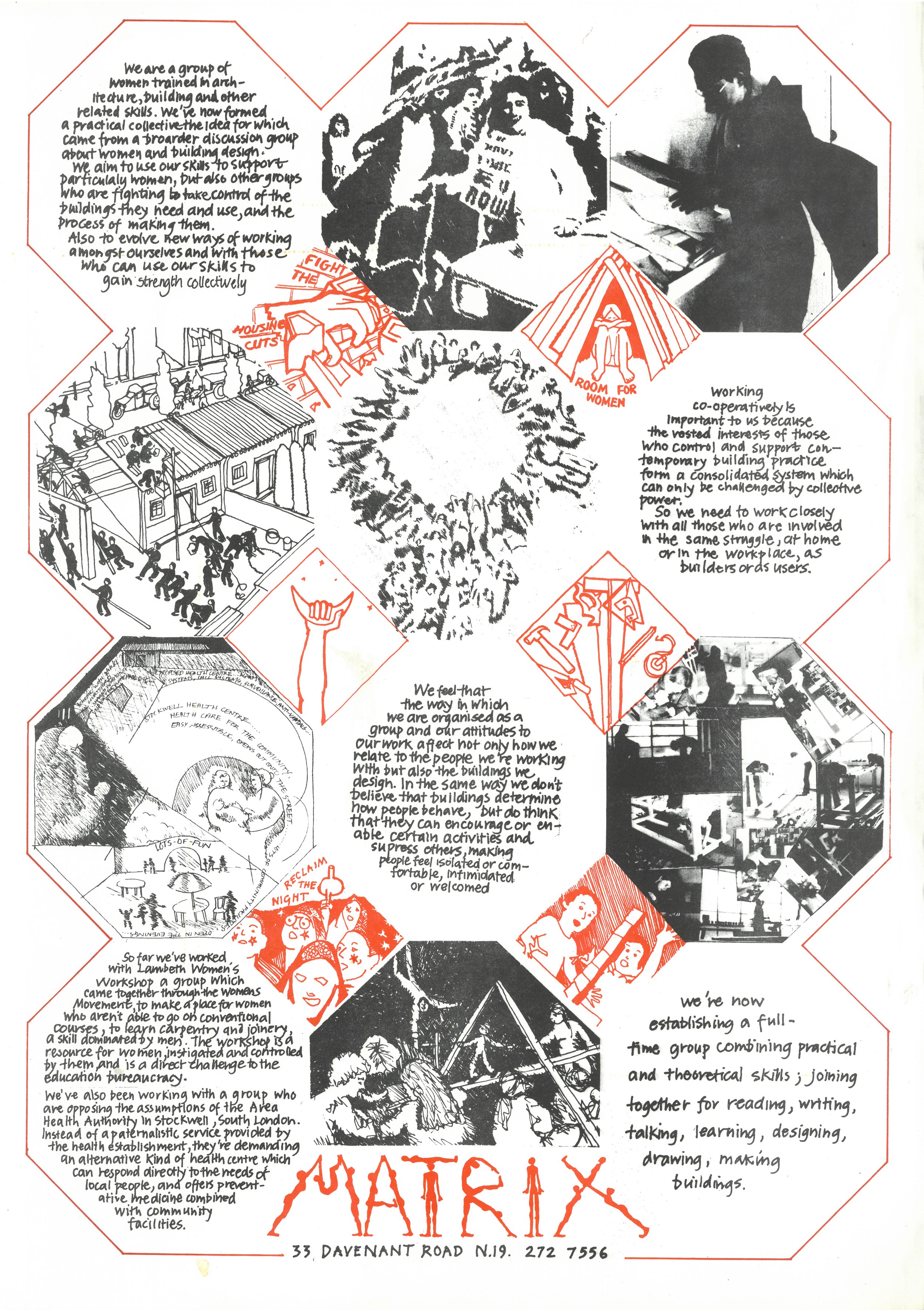

Jos Boys It grew out of something called the New Architecture Movement, which was unionising architects nationally towards the end of the 1970s, as well as Community Technical Aid Centres – shopfronts providing direct architectural services to community groups. London was very derelict at that time, and community groups were resisting office developments being thrown up. Out of that, the New Architecture Movement developed a feminist wing. It was still a time when those left-wing movements were very male dominated and women were expected to just make the tea. I met the women who actually set up the practice in the early days, such as Anne Thorne, Sue Francis, Barbara McFarlane, at that time. I was working as a freelance journalist and squatting in Covent Garden. I had an office at Five Dryden Street, partly because I was squatting around the corner and we didn’t have any washing facilities, and partly because I was a freelance journalist and I could rent a shared desk. It was one of the first WeWork-type offices, but with a much more community-based understanding. I had access to all this kit like Xerox machines and receptionists. It was quite anarchistic and the basement became a place where we had our meetings, which I remember as being really full: like, 60 women turning up. Out of that discussion group there was a relatively amicable split between women who were more interested in how women could be much more equal within the architecture profession, and women who thought that architecture as it was taught and done and practised needed to change completely. In that first camp there was a group called Mitra, which did organise as an architectural practice for a bit, but Matrix really grew out of the feeling that the way to move forward was to have a design practice. We did a couple of schemes, not under that name, which didn’t come to anything, but they did began to clarify this idea that that you could have a feminist design practice.

Ann de Graft-Johnson Part of the discussion was questioning the nature of architectural education and the culture of the profession. Quite a few of the women involved in the early days were resisting becoming architects, because they didn’t feel that the culture accommodated the practice and ethos that they went on to adopt. Most of the women studied architecture, but there were also journalists and writers. It was broader than just people who had architectural training. There were people who wanted to become architectural practitioners but didn’t want to qualify, although most members of Matrix did end up qualifying as architects at a much later date. When I joined the practice in 1985, I was one of the few people who was actually a qualified architect.

Jos There were also all those other connections from people involved in community action and squatting. Women like Julia Dwyer, who came into it through her experience setting up lesbian households in derelict houses; being interested in training in architecture and then becoming disillusioned by the way architecture was taught. Mo, your experience was similar?

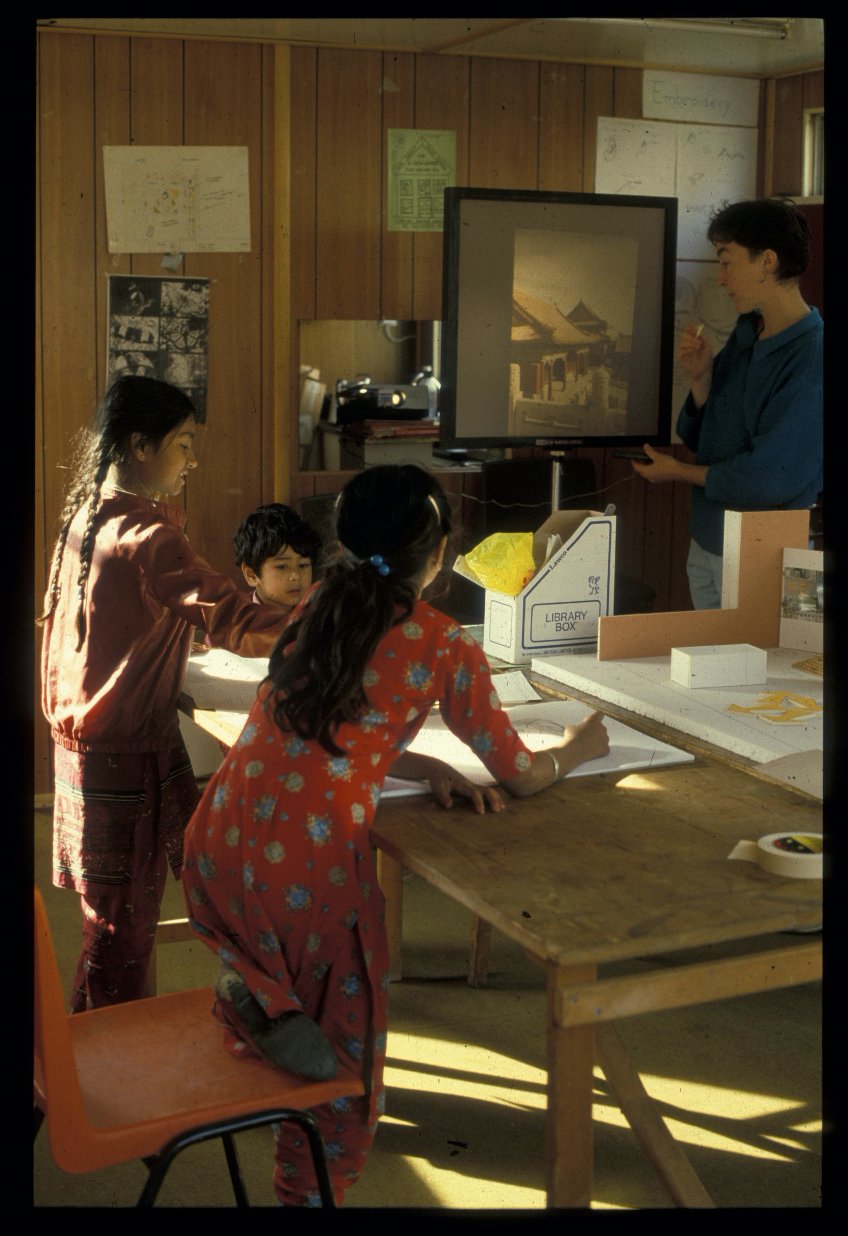

A photo from a consultation for the Jagonari Asian Women’s Centre (1985).

Mo Hildenbrand I trained as a social worker but got frustrated. Working with community groups and in a women’s refuge was important for me. When I came to England, I lived in London Fields in a mainly lesbian housing co-operative that got funding to buy houses and refurbish them. I was interested in studying architecture from having been a part of that building process.

Jos We should mention Sue Francis, too, and Fran Bradshaw and Mary-Lou Arscott – all people who were very much involved in building as much as architecture, having studied architecture.

Ann Fran became a bricklayer, but she was in the same year as me at Newcastle University. I’m a university dropout and then went to the AA to complete my Part One and Part Two, whereas Fran did Part One and Part Two architectural studies and then decided to go into manual trades, before joining architectural practice in later years.

Viviane How did this actually work in terms of daily practice? How did people become a member of Matrix?

Mo When I applied it was a very detailed application. I got the job after an interview, but there was a probation period of half a year and an interim assessment. You took part in all the meetings all the time, and also worked on budgets. For me, it was actually quite difficult, because I had just finished my Part One, so I did not have any experience whatsoever. I was thrown in at the deep end. But after half a year, I became a full member of the cooperative and had full responsibilities for the practice and projects.

Ann We were very clear about the job description, but we also had a person specification. It was a tight system. We anonymised recruitment, so details about identity were separated out from the actual application. Today, I work in a university where we still don’t have anonymous recruitment. One of the critical issues was that we were trying to make sure we were diverse. Making difficult decisions about whether or not somebody met the equalities criteria was quite often a problem. There were times when, although we’d shortlisted people, there was nobody who we felt met the standard. That was very difficult. We had racist micro aggressions – somebody coming for an interview and just barging past us when Gozi [Wamuo] and I went to answer the door. We were actually running the interview, so you can imagine that that didn’t go down well. That person lost the job before they even crossed the threshold, frankly. We were working with diverse groups, so it was important to build engagement and not make stereotypical assumptions.

A wheelchair accessible shower in the Essex Women’s Refuge (1992).

Mo Most of us worked very, very long hours, including Saturdays and Sundays, just to keep it going. Everything was discussed. The finances, which everybody was responsible for, as well as policy issues. We discussed each project in full.

Viviane Was there a particular atmosphere in London at that time that made it a fertile ground for these discussions? When you talk about the squatting and cooperatives, it seems like there was an atmosphere for experimentation and discussion; that everyone was campaigning for better conditions.

Ann At the time, the Greater London Council (GLC) – before Margaret Thatcher managed to abolish it – was very supportive of different groups. A lot of funding went to lesbian groups, gay groups, women’s groups and Black Asian and minoritised groups. Matrix was one of the practices which offered technical aid and fell within that bracket. The Jagonari Asian Women’s Centre [an educational centre for Asian women designed by Matrix in Whitechapel, London, ed.] was one of the last – if not the last – projects to get funding through the GLC. Matrix was working for community-based organisations through that funding, with groups like the Claudia Jones Organisation [a London non-profit providing services to women and their families of African Caribbean Heritage, ed.], which was looking at Saturday schools because of what was happening to Black pupils who were not getting equity in education. There was dialogue between different, diverse communities, and ongoing discussion within Matrix about what is feminist practice. What is feminism? How do we approach working with people in a collaborative and participatory way? The office protocols and structures were very well thought-through when I joined. It was a completely different way of working.

Viviane What were the ideas that resonated with you?

Ann The commitment to the rigour of how you practise architecture, which included accommodating people’s lifestyles. The fact that women who had children were accommodated with core working hours; having a minimum of two people on every project so there was continuity; a non-hierarchical basis and everybody having equal wages; an assumption that everybody can take responsibility for decision making. Some of it didn’t work, but quite a lot of it did.

Feminist analysis of building design guides and marketing material.

Viviane How did it turn from a place where you regularly met and discussed into an actual practice with projects?

Jos Those things happened in parallel and were to do with different groups of women who came together because they were more interested in particular aspects. Via Sue Francis, we got asked by Stockwell Health Centre to help them out with a redesign. They were quite radical, but they’d had a conventional architect and disliked what they had done. I got involved in that, but it still wasn’t under the name Matrix. That happened when we moved on from squatting in Covent Garden and into what was called short-life housing. The front room of those houses was the seedbed of what became Matrix. As for the book, the group of women [working on that] overlapped in some ways with the practice, but not in others. There were women who just worked on the book group, but weren’t involved in the practice. In the early days, anyway, there was also a support group of women who were already in practice and were experienced. The early workers were straight out of architecture school, so there was a network of [more experienced] women who did that role in an unpaid capacity.

Ann There was a lot of discussion about protocols. Through developing the publications and the talks, we were able to describe what kind of processes we adopted. For example, recognising that quite a lot of our client and user groups would be laypeople who may not necessarily be able to read architectural drawings. So processes might include offering training in reading drawings and adopting techniques for getting across spatial understanding. That might be producing rough working models that didn’t feel intimidating. Sometimes, if they were in existing premises and we were either designing a new build or adapting those premises, we’d mark the layout of the existing floor with the proposals for the model, so that they could have an idea of scale. Sometimes it would be about going on visits to different projects so that they could see pros and cons and talk to people staffing the place. It was thinking about different ways of looking at the process, not just, “We’re experts, this is the design you’re going to get.” Obviously, the argument against that is how time-consuming it made the consultation process. But we were able to gain a much better understanding of the user’s needs, and some of the actual buildings worked better as a result. I don’t know whether Mo would agree, but quite often the aesthetic wasn’t as important as the process. Aesthetics were important, but they needed to reflect the culture of the organisation. Most of us had gone through a modernist education, but it wasn’t really our remit to impose that model on our client groups.

Mo The most important thing was to incorporate the end-users’ views into the design and into the final building. With the women’s refuge in Essex, for example, the external design was not imposed on the end users, even if the ideas came from us.

Mockup of the front cover for Making Space: Women and the Man Made Environment, Pluto Press, 1984.

Jos If we’re talking about the cost of consultation, the thing that I didn’t know about until we were developing the Matrix online archive was how much funding there once was for feasibility studies.

Ann That was what enabled Matrix to offer the kind of service it did. When that funding went, it seriously impacted on the groups we could work for. It removed a community layer and it left us working on housing association projects where there wasn’t the scope for participatory approaches. I would basically be finding a site, working out density requirements, and producing proposals. We weren’t necessarily involved with the user group and it very much depended on the nature of the housing association representative. With the Essex Women’s Refuge, that was a project which straddled the government rates cap, and a housing association rather than the local council took over as the client. This impacted on the inclusivity of the design. We’d originally designed the lift to go up to the top floor where women could bring their possessions, and donations of clothes and toys could be stored there. It was supposed to be wheelchair accessible. When it was taken over by the housing association, they refused to endorse having a lift up to that level. We did manage to win the battle of not having the wheelchair accessible bedroom being on the ground floor, but that housing association went against the ethos of what we were trying to do.

Mo Having an accessible bedroom on the first floor was for the safety and security of the women. A lift to the first floor was absolutely necessary.

Viviane Why was the budget for feasibility studies cut?

Ann Because Margaret Thatcher didn’t like the fact that the Labour-led GLC was bang across the river from Westminster. She managed to dissolve the GLC and the London Boroughs Grant Scheme came in instead. We did get funding from the London Boroughs Grant Scheme – for a couple of years. Then, although the grant schemes officer had said they were going to support the renewal of our funding, when that meeting actually came, it was a case of “Off with their heads” and they discontinued it. It was really problematic because the groups that lost their funding were mainly Black and Asian-led projects. The Boy Scouts, which had at least £3m in the bank, got their funding. It was a rout.

Jos What was brilliant about the funding for the feasibility studies was that it enabled not just Matrix, but lots of architectural practices interested in participation. It meant that you could work with users to think about what was needed, be supported in writing a brief, and in doing costing. A very good example is Jagonari, where the client group assumed that all they would be able to afford would be a few porta-cabins. Working with Matrix, they could discover what they actually wanted. It gave time to talk things through and think about the design implications and the cost, the budgeting implications, and to be supported in making an application. They could meet their ambitions. Relatively speaking, it was a big and generous scheme for a community-based project, and that feasibility study enabled that building to happen in an equitable way. That feasibility funding was also good, solid, daily income.

Meeting notes from the Making Space book group.

Ann We had an annual income, obviously, and we had to do reports on how the money was spent. But it did allow lots of groups that wouldn’t otherwise have been able to resource it to get to a point where they could put in for funding to actually realise a project. With Jagonari, it enabled extensive cultural conversations. Meetings carried on during construction, discussing aspects such as having a mixture of Indian continent toilets and Western toilets. There was a detailed discussion about being really mindful about security, because there had been a lot of racist attacks at the time, but trying to treat the building elevation in a way that was positive in terms of sending a cultural message, rather than a building that looked like a castle.

Viviane That example illustrates how all these processes are driven by the structures and policies around it. You did these participatory processes which, until I discovered Matrix, I thought were only a recent discourse in architecture education.

Jos When I studied architecture in the 70s at The Bartlett, UCL, it had a radical moment. A lot of the people studying there were also working in community action. Participation was very current. Nick Wates [a writer and project consultant specialising in community involvement in planning and design, ed.] in the year above me wrote a book called Community Architecture and we were reading books like After the Planners [a 1971 text by Robert Goodman, ed]. There was a lot of stuff going on in the States about grassroots community action around architecture and cities. The way that Matrix did it was very current in recognising that the language of architecture and its tools, such as plans and sections and elevations and models, are often alienating. In terms of a general ethos, we needed participation in this process.

Ann It’s very much dependent on what architecture school you went to, because Newcastle wasn’t like that. I went to the AA because Paul Oliver [an architecture historian and expert on vernacular architecture, ed.] was teaching, but the year I joined I think he’d fallen out with Alvin Boyarsky [the chairman of the AA from 1971 to 1990, ed.] and left, and Brian Anson [an architect and planner who lost his job at the GLC when he joined local residents in protest against the demolition of buildings in Covent Garden to make way for car parks, ed.] had also left. By the time I got there, that kind of ethos had disappeared.

Mo When I was at architecture school in the 80s it wasn’t really discussed. But what was interesting when I studied at the Polytechnic of North London was the woman’s access course [the Women into Architecture and Building (WIAB) was founded by Yvonne Dean with Matrix members including Susan Francis to teach courses helping women enter the built environment sector, ed.], so women who didn’t have the A levels to enter architecture school could go through that way.

A poster for Women’s Realm: A Weekend Event on Women, Building and the Environment held at the Polytechnic of North London (1987).

Viviane London at that time sounds like a kind of paradise compared to now, although I have to be conscious of not romanticising it. Was it a conscious decision from Matrix to only work on public schemes?

Ann We didn’t turn down private schemes. In fact, we did go for a number of private schemes, but there was quite a lot of sexism going on. We were put forward to go and look at some premises in terms of designing offices for a bank. I think we made the mistake of saying, “Why do you want to be on the top floor?” So we failed the interview. In terms of Jagonari, there was a lot of support from the then GLC from one particular person and they went on to London Docklands. They tried to recommend us there, but people were very suspicious of an all-women practice that called themselves feminists so we didn’t succeed, even though people were trying to put us forward for private projects. We had discussions with banks who were looking at having crèches and nurseries associated with them, trying to increase staff gender diversity. But I don’t recall any of those actually coming to anything. We wouldn’t necessarily turn down a private project, unless it was iniquitous, but we did have a way of working that didn’t always fit what they were expecting.

Viviane In her foreword to the reprint of the book, Katie Lloyd Thomas said there wasn’t much interest from the architectural profession at the time. What’s your recollection of the climate back then?

Jos It was very much a time when it was generally assumed that the built environment was neutral and wasn’t affected by gender or race or sexuality. It was a gentleman’s club – this idea that professional knowledge and balance and compromise would give you the best solution. There was no idea about bias. Even the word sexism was still relatively new, so there literally wasn’t the language to talk about it. Putting the book together was about trying to find that language. When I gave talks to the architecture profession, I found responses generally tokenistic. They couldn’t grasp the idea that it should change anything about how they worked. I was told that it’s good to have some women in architecture because they could—

Ann —design kitchens!

Jos Exactly. Design interiors. Then you’d go off and have kids and that would be the end of it. A “waste of money”. That was the 70s and 80s.

The Cover of Making Space: Women and the Man Made Environment, Verso, 2022.

Ann When we were doing our paper ‘Why Do Women Leave Architecture?’ [a University of the West of England report for the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) diversity panel Architects for Change (AFC) written by Ann, Sandra Manley and Clara Greed, ed.], which was published in 2003, one of the interviewees said that women were doing interiors, and men the exterior design. There was still that pattern of behaviour going on in terms of gendered allocation in work.

Viviane It’s still going on. You look at any architecture school, the interior design course will be packed with women and the architecture students doing parametric modelling are the technical guys. Even when I was studying, I wasn’t aware of things like gendered space. I’m interested to hear what it feels like for you now, because suddenly there’s traction. The language exists to name all these issues so perhaps we can get closer to them. But does it feel, for you, a little bit like “I told you so”?

Ann Well, yes. What’s that film called – Groundhog Day? Sometimes it was difficult that there were things that just didn’t get a platform for discussion, but a lot of the discussion around process was productive and constructive. There was a certain amount of autonomy in the practice, rather than working for a conventional architectural practice with a very strict hierarchy. The last practice I worked in I was very definitely de-skilled. There wasn’t any autonomy, my opinions weren’t respected, so I ended up needing to leave. Whereas in Matrix, we did work very hard, but the people who worked and stayed were very, very committed to the core ideals.

Mo What I find nowadays in the workplace is that young women don’t know anything about Matrix. When you talk to them about it, they may be interested, but they’ve got no clue.

Ann Matrix was unique, perhaps, in bringing together lots of ideas, but the ideas weren’t new. It was a combination of being born out of different movements, but also bringing in people like me – I wasn’t involved in any of the movements before I joined Matrix. It wasn’t a homogenous group of women all coming from the same background and the same starting point.

A hand-drawn promotional poster for Matrix (1979).

Jos These things hit a moment, they trend, they fade, and then they come back again. I’m getting a flurry of requests at the moment to talk about how to make cities safer for women. Right. Fuck that for a laugh! There was plenty of work done in the 1970s and 80s, and huge numbers of publications done by the GLC and the Women’s Design Service. The problem is men still asking women how women can make themselves safe, and how the design of the built environment can make things safe. I get asked to explain, yet again, to white guys, what the problem is. What’s great from Black Lives Matter and #MeToo is it puts the burden onto the dominant groups. Whether that’s being white or middle class, or being male, or just being an old fart. Putting the burden back onto those people to think about this, and actually investigate this themselves, rather than endlessly leaving it up to the minority groups to do all the work and do all the continual persuasion. It does go round in circles, which has to do with power and how dominant groups reclaim their territory. It’s interesting why Matrix is suddenly back in and gender and architecture is back on trend and in the discourse. The stuff I do around disability is on trend now, too. It’s really weird. It’s not like disabled people haven’t been campaigning for access since the 1960s.

Ann We have what I call a very contradictory situation, certainly in the UK, where on one level, we’ve got culture wars and dog whistles, and at the same time we’ve got much more grassroots activism and Black Lives Matter. And they’re on a collision course in terms of who’s going to win that dialogue. I think it’s quite a precarious time, frankly.

Jos The thing that was really important about Matrix was it focused on more than the user. It was empowering not just by recognising that people didn’t understand what the tools of architecture were, but by acknowledging that users are not a homogeneous group.

Ann Even at that time there were other practices working on a so-called participatory process basis, but it was quite often incredibly tokenistic or excluded certain groups. There was a power structure that meant only certain voices got heard or, in some instances, no voices got heard. There’s a scheme in Peckham, for example, where the architects were proud of having kept a very narrow width with the layout, but it has a kitchen and a dining room on the ground floor as separate rooms. This was, and is, an area where there are lots of quite large families, five or more people, quite often with small children – it’s difficult to supervise small children in the way that these house plans were divvied up. It became obvious that the plans were ones that suited the architect in the practice. Similarly, there were conversion projects where, because that particular architect didn’t like sinks under the window, it meant a family-sized fridge couldn’t fit anywhere or else you took out the dining space. People weren’t considering the family structure or the culture. You get this white layer, this middleclass layer, from an architect about how they perceive a living space being imposed onto the people who are going to be in it.

Part of a leaflet for Women’s Education in Building, advertising courses in trades jobs run by and for women.

Jos Matrix refused to just have this notion of “the user”. The thing was really unpicking that, listening to those diverse experiences, and trying to engage with them and understand how space is gendered.

Ann Adding to that, the Jagonari Asian Women’s Centre entrance and the treatment for the ground floor were very different to how some of the white-majority women’s centres were. Quite often those had a shop window frontage that was more transparent. Whereas with Jagonari, because of racist attacks, it had to have a defensive entrance that opened out as you went into it. Matrix acknowledged that women aren’t all the same. That there are different issues that people face. That included things like, with Jagonari, not meeting after dark, because safety was more of an issue in relation to those women, whereas we were meeting after dark with white women quite a lot, even though it was the era of Reclaim the Night.

Viviane How did the archive come together? When you look at the archives of many architectural practices, they have models and plans of buildings that were built, but Matrix was about so much more than that.

Jos The [Matrix Open feminist architecture] archive was almost accidental. It came out of some of us meeting every now and then over about two or three years to talk about getting the book re-published, because it was unavailable. We all kept getting emails saying, where can we find the book? I don’t know how much you paid for it but it was going for £350 online.

Viviane I found someone in Sussex who had no idea and auctioned it on eBay for £9, so I pounced. I had an alert set up, because the museum would have been prepared to pay £400.

Women measuring a floor plate on a building site.

Jos Of the group of us who met over the book, two of the women sadly died in relatively quick succession [Sue Francis and Julia Dwyer, ed.]. So that focused our minds on both the book and [the archive]. For practices like Matrix, community-based practices operating in that pre-internet period, stuff is just under people’s beds and in cupboards in Ikea and Tesco bags. There was no sense of a collection in the way that a lot of traditional architectural practices have some sense of their legacy. I managed to get a little bit of money from my employers to help in this process. It’s been completely precarious, because it has depended on the goodwill of a very large number of women, including Mo and Ann and Gozi. Some women have vanished into the ether. People assume that the Matrix archive is what they can see from the website, that it’s a kind of collection or it’s in an institution. We’re increasingly being asked for permission to use stuff from it. I’ve no idea how that works. And I’ve no idea how long I’m going to be responsible for making that happen. It’s a rather random process, but for me it was a way of honouring Julia and Sue, and feeling that if we didn’t do it now, it would all get lost. A lot of it has been lost already.

Viviane What were some of the surprising things that came to the fore that people had under their beds? So much of your work was based on the process of the discussion, the research that was going on, that the final projects are only part of your legacy.

Jos How do you make an archive? You make an archive out of what people have and are willing to share. And a lot of that is handwritten and hand drawn, even if Matrix was quite early in using computers. I can see from the paperwork, the handwritten minutes from all those meetings, how exhausting they were. There’s resignation letters and some of the paperwork that Ann mentioned, the forms for recruitment. The complete specification of Jagonari – someone sat there and typed all of that. That’s what makes a building a feminist building – a huge amount of work. We’ve all been really interested in not just sticking to the building plans. The models don’t exist anymore and we either can’t find the drawings or they’re in the RIBA Drawings Collection, which won’t let us access them unless we pay. It really needs somebody, or a group of people, to commit their lives to it.

Ann I don’t know whether it comes across in the archive. But the process largely contributed to the current users’ feeling of ownership. There is a drawing in the archive of the proposal for the Brixton Black Women’s Centre, which never went ahead, but got taken over by the council where it became about saying “You will have this,” whereas we were trying to work with a participatory process. At certain points you could see the guy from the council we were supposed to be dealing with crawling past the door to avoid coming into a meeting. Even though it was a female architect who took it over from us, she didn’t recognise the fact that you have to co-create. We didn’t have the terms “deficit model” and “social model” back then, but there was a continuum of deficit model, and we still have that in terms of social housing. It’s very difficult to get away from that and it goes into cycles. The next generation has to relearn it and then describe it as being innovative when it’s actually decades and decades old.

Introduction Viviane Stappmanns

With thanks to Jon Astbury

Making Space: Women and the Man Made Environment by Matrix is published by Verso, price £14.99.

This article was originally published in Disegno #32. To buy the issue, or subscribe to the journal, please visit the online shop.