Beta Testing

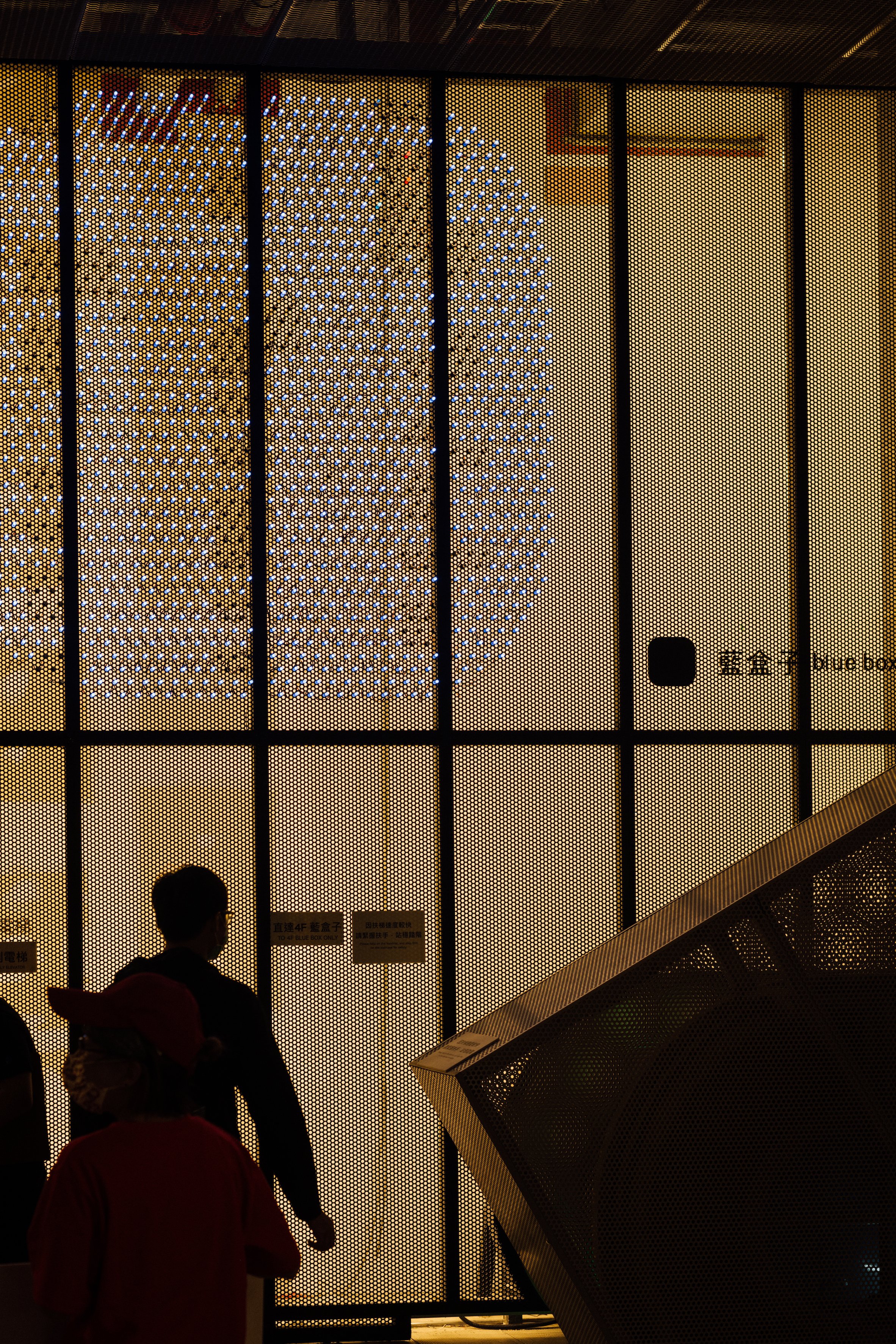

(image: Tei Koukei).

Like most high-profile architectural projects in Taiwan’s capital, the OMA-designed Taipei Performing Arts Center (TPAC) has experienced significant delays in construction. Originally planned during the 2006-2014 mayoral administration of Hau Lung-bin as part of a competition conducted in 2009, and having broken ground for construction back in 2012, the building is now open – seven years later than originally planned – for a trial period running from March to May 2022. Costs for the building, which is owned by the Taipei city government’s Department of Cultural Affairs, eventually came to 6.7bn NT (around £178.3m), a marked increase on its initial budget of 3.8bn NT. It is one of the most expensive development projects in Taipei’s history.

TPAC has been billed as a new focal point for the performing arts in Taipei. While most theatre complexes in Taiwan’s capital are situated downtown, TPAC stakes out its claim slightly outside of the urban centre, in a part of the city that reaches towards the Yangming Mountain that overlooks Taipei. The building is set to host both experimental productions and more commercial fare in its three theatres, with the centre comprising a glass cube with a large silver orb protruding from one side (the site of one of those three theatres), along with two further projections (the remaining two theatres, which can also connect together to form a single larger space). It strikes a distinctively more contemporary profile than the city’s existing performing arts centres, which more often feature neo-classical Chinese stylings, as with the National Theater and Concert Hall.

When Taipei’s current mayor Ko Wen-je took office in 2014, he insisted that the centre would be completed within his initial four-year term. He doubled down on this promise the following year, stating that it was akin to a “military order” that the project had to be completed by 2016. Yet 2016 in fact saw the sudden cessation of work on TPAC, when the International Engineering and Construction Company, the contractor for the project, went bankrupt, owing subcontractors more than 80m NT for building materials. It was later found that the company actually owed more than 2bn NT, having accepted a 760m NT loan from the city government after taking on the project, while concealing a loan of 540m NT from 11 banks in 2011. At the time, Ko – a figure frequently drawn into political controversy due to his tendency to exchange barbs with opponents and to venture off-script with public comments – stated that he would “strangle one by one” each of the officials responsible for the construction of the project if they were unable to complete it according to his schedule. Evidently, neither the strangling nor the completion of construction took place.

By the time the official launch of TPAC takes place later this year, Ko will likely be out of office having served a full two terms, with fresh mayoral elections slated to take place in November 2022. Yet such issues are far from uncommon in the Taiwanese construction industry, particularly with regard to companies bidding on expensive tenders from the government. Things become all the more fraught in relation to projects that carry high international prestige through their architects, with mayors sometimes touting such projects as part of their legacy: particularly if they have future political ambitions. The National Kaohsiung Center for the Arts, better known as Weiwuying, for example, was designed by Mecanoo Architecten and built under the 2006-2018 Kaohsiung mayoral administration of Chen Chu. Opened in 2018, Weiwuying is the world’s largest performing arts centre housed under a single roof, but the space has attracted criticism for its budget of 10.7bn NT and the fact that seven comparable venues already exist or are currently under construction in Kaohsiung. “Is there really a need for eight such venues in a city of just under 3 million people?” asked a critic writing under the pseudonym David Evans in Taiwan’s The New Lens. “Do they offer the residents of Kaohsiung value for money?” Reflecting on Chen’s motivations for authorising Weiwuying and other projects during her administration, Evans further noted that “[perhaps] it was inevitable that she would seek to leave a lasting, physical legacy of her time in office, as many mayors are wont to do. It is just unfortunate that her focus was on grand infrastructure and building projects rather than improving public services and the lives of the city’s people.”

Whether Weiwuying proves its worth remains to be seen (it says that it received 800,000 visitors in its first nine weeks after opening, but more recent figures are not readily available), but there are wider concerns within Taiwan about the risks of “white elephant” projects – prestige commissions that are often seen as failing to connect with local residents and which run the risk of falling into Taiwan’s long history of expensive public properties that ultimately sit derelict, having been built to advance the career of a local politician. Further examples of this phenomenon include the Yingtsai Academy in Miaoli, which in 2015 reported receiving only 10 visitors per day, despite having cost 91m NT, or the Hakka Roundhouse, also in Miaoli, which similarly receives few visitors despite a cost of 64.8bn NT. Both structures are thought of domestically as the pet projects of Liu Cheng-hung, Miaoli county commissioner, who was likely hoping to leave his stamp on the region. In fact, so familiar is this phenomenon in Taiwan, that there is even a term for these disused public structures: “mosquito halls”, in reference to the fact that their only occupants are insects despite construction costs having potentially run to hundreds of millions of new Taiwan dollars. The term was coined by art critic and historian Yao Jui-chung, with notable mosquito halls including the 3.1bn NT Linnei Waste Incineration Plant in Yunlin and the largely empty Changhua Coastal Industrial Park, which was built for a staggering 123bn NT but is now scarcely occupied. White elephant projects, those underused public structures that are intimately linked to the careers of local politicians, can be thought of in a similar vein. Although most have not yet become fully fledged mosquito halls, and their cost is many scales of magnitude higher, there is a fear amongst members of the public that they too may share a similar fate.

Given the international pedigree of its architects OMA, TPAC has always had the potential to become a political lightning rod, but to date it has largely been spared detailed scrutiny during Ko’s administration. Instead, the combative mayor’s attention has been taken up by the saga of the Taipei Dome, a stadium designed by Populous for Taipei’s Xinyi District. The Dome began to be constructed in 2012, but it became mired in controversy when Ko ran for election in 2014, using his campaign to criticise the scheme for corruption and mismanagement. Ko had originally called for the dome to be demolished after its construction was halted for five years from May 2015, but he has more recently switched to pushing for its immediate completion, seemingly mindful of its potential role within his political legacy. Operating within a similar timeframe, the Taipei Music Center (TMC), designed by Reiser + Umemoto, is another high-profile project designed by a prominent international architecture firm, which opened in September 2020. This building, too, was an expensive project that premiered with much fanfare, but which has prompted questioning as to whether it can genuinely carry out its purpose of providing a home for Taiwan’s vibrant music scene. Although the TMC hosted Is Your Time, a high-profile 2021 exhibition by composer Ryuichi Sakamoto and artist Shiro Takatani, it has otherwise not managed to stand out amidst the city’s existing programming, with relatively few high-profile domestic or international exhibitions or performances having taken place there. The TMC offers a parallel to TPAC, then, in terms of the challenges facing a prestigious cultural structure aiming to fulfil its intended purpose.

For a theatre of its size, TPAC sits on a relatively small plot of land directly adjacent to the Jiantan MRT station. The centre overlooks the Shilin Night Market, one of Taiwan’s major tourist attractions in non-Covid times and a hot spot for street food. This location in northern Taipei, just outside of the city centre, situates TPAC alongside other art infrastructure in the Shilin-Beitou area, including the Taipei Fine Arts Museum and the National Palace Museum. The location also serves to distinguish TPAC from what is likely to be its direct competitor, Yang Cho-cheng’s National Theater and Concert Hall, located next to the Chiang Kai-shek Memorial in Zhongzheng District. Nevertheless, there are limitations to the location in Shilin: the Shilin Night Market is primarily tourist fare, for example, and not where locals go for street food. And although TPAC may draw students from the nearby National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University, it is farther away from arts universities that would likely bring in students with more of an interest in attending performances, such as the Taipei National University of the Arts or National Taiwan University of Arts.

In response to the strictures of the site, OMA has responded accordingly. “We made this vertical, stacking theatre instead of a horizontal, spread-out theatre as most other theatres would do,” says Chia-ju Lin, senior architect and building site manager, who emphasises the structure’s vertical nature. “It brings in this Z-direction instead of only X and Y.” This same theme is picked up by David Gianotten, an OMA managing partner and architect, who describes the theatre’s structure as reflecting its environment in that the Shilin night market is itself “super-efficient, super-compact, and focused on functionality”– an interesting take on a space that is usually described in terms of rowdy hubbub or urban chaos. Consequently, the “aesthetics of the building are very much based on the functionality.” In this respect, Gianotten describes the centre as “a machine for theatre-making rather than an aesthetic theatre building.”

Functionally, TPAC combines three theatres, which are joined together by a boxy central frame that provides the central hub through which visitors move, with the theatres themselves external to this core. The design emphasises the distinctions between these spaces, which have each been assigned a unique spatial profile and colour scheme. As represented in the building’s wayfinding and iconography, the three theatres have individual profiles that make them recognisable from each other, while colour coding helps distinguish the functions of spaces: neutral greys denote areas for the public, blue signifies theatre spaces, green designates offices, and pink points out rehearsal spaces.

The most unique feature of the TPAC, however, is its Public Loop (stylised on the building itself as the “Public Loooooop”), which allows visitors to enter the building and view the many layers of the theatre within, all without attending a dedicated performance, and at no charge. Not only does the loop let members of the public passing through the building view snippets of the performances happening within the theatres, but it also allows for a peek into backstage areas of these spaces, which remain hidden in a more traditional theatre layout. Passing these area, the loop then links through to the café rooftop, and assorted terraces – spaces that allow for fleeting glimpses of the sky and surrounding city from within the structure. “That moment of reflecting where you are, was very important to us,” says Gianotten. “That tells a story of the city, of the energy, and gives you the opportunity to step out of it for a moment and reflect. For us, that is an important part of architecture.”

As a linear route passing through three-dimensional space, the Public Loop is an entry point into various aspects of the “machine” as a whole – albeit one that offers a highly curated perspective. The loop aims to allow for a glimpse into the inner workings of the theatre, with its colour coding allowing viewers to know at a glance what purpose a specific area serves – an intimate experience of rehearsal spaces or ongoing performances, all seen through soundproof glass. It remains to be seen whether this experiment pays off, or whether it serves to make the theatre itself into a form of spectacle. Actors, performers, backstage theatre personnel, office workers, and others may ultimately find that allowing the public this level of access is intrusive – an act of putting them on display in spaces that would typically be considered private. Alternatively, the building’s staff may find themselves “acting” and “performing” in areas of the building in which they are visible to members of the public, thereby making the performing arts centre itself into a form of performance. But although it may prove to have elements of a voyeuristic panopticon, the Public Loop’s dissolution of the border between public and private is intended to draw more members of the public into the theatre. In this way, the space is “exposed to people who still need to go over the threshold of going to the theatre,” says Gianotten.

Still, it may not be surprising to learn that TPAC has already drawn controversy – some serious, some less so. In a process familiar from other high-profile OMA projects, the TPAC’s architecture has been singled out for a number of humorous comparisons, such as how the CCTV Headquarters in Beijing came to be known as the “Big Pants Building” or the Shenzhen Stock Exchange was termed the “Miniskirt”. In particular, the TPAC’s round structure housing one of the theatres, and the overlapping blocks that comprise the building’s lobby and other two performance spaces, have drawn comparisons to compositions of pig’s blood cake, fish balls, and tofu (all local Taiwanese delicacies) in a number of internet memes. This may be appropriate given that these are among the street food sold at the nearby Shilin Night Market and, fortunately, the building management has taken the jokes in good humour, offering these dishes arranged in the shape of the building within its café. “We hope that after they’ve eaten the dish, they go through the building and see what it provides,” Gianotten comments wryly. “The fact that people make it their own, speculate about it, and comment is a good thing,” he explains, adding that he rather enjoyed the memes. It is a point echoed by Lin. “The question is if the building is creating any interesting discussions or generating new energy for public life,” she says.

Yet what has been more deeply controversial is the rollout of the centre. Although the outside of the building looks complete, the interior is still visibly in a state of construction, including aspects of the theatres. While this has been framed as part of TPAC’s trial period, and as part of the building’s fine-tuning before its formal opening later in the year, the unfinished nature of the space has taken some by surprise, as reflected in coverage of the opening by domestic media. It is unclear whether this extended rollout period is due to the significant delays in the building’s construction spilling over (or even an attempt to ensure that the building’s opening can be framed as taking place under Ko’s mayorship rather than a successive mayor’s), but the public is not used to this kind of debut for a project that they imagined to be in a high state of completion. For their part, both Gianotten and Lin emphasise the experimental nature of the structure. Continuing his machine metaphor, Gianotten compares the rollout to the process of software installation for a computer, while underscoring that the building has “all kinds of possibilities that you need to settle in.” Nevertheless, with the TPAC having been under construction for so long, some parts of the building may actually need refurbishing before the final launch, having been worn down over the past 10 years.

Still, delays are not unusual in Taipei, and this has not prevented previous construction projects from becoming objects of public pride down the line. The Taipei MRT metro is one example, with polling from 2003 showing an 86 per cent public approval rate for the MRT, less than 10 years after opening following decades of construction with no clear timeline for its completion. The Taoyuan Airport Express is another example of infrastructure that was opened in a partial state of completion following long delays. It remains to be seen whether the TPAC can be integrated into Taipei’s urban landscape in the same way. The public – and stakeholders such as the politicians who have overseen TPAC’s construction – were likely hoping that the structure would make a triumphant splash upon opening, grabbing headlines that would allow the project to be touted domestically as a political accomplishment. Yet although the structure has received some international attention, domestic responses to date have been more muted. One factor in all this is the pandemic, which has cut off ties between Taiwan and the international community, with Taiwan only gradually reopening its borders now, having maintained a Covid-zero approach for the duration of the pandemic. This policy has likely dampened domestic reception of what would otherwise have been a far more grandiose international opening.

Given its lack of recognition as a sovereign state by the majority of the world’s countries, Taiwan is often desperate for international recognition and achievements that it can tout on the global stage. More often than not, Taiwan is overshadowed by its significantly larger neighbour, China, which is also its largest geopolitical threat. China claims Taiwan to be part of its sovereign territory, despite Taiwan’s self-ruled, democratic government. Indeed, the last time that the same political entity controlled both Taiwan and the Chinese mainland was in the 19th century. As such, whether in terms of architectural distinctiveness or as a vibrant cultural hub, recognition is likely what Taipei’s politicians and the publics they serve had hoped for from the TPAC. In this sense, the pursuit of global architectural distinction is in line with Taiwan’s broader aspirations for international acknowledgement. Indeed, the aping of what is perceived as “international” is, in itself, an undercurrent of many architectural styles found across the country. As has been observed by critics and academics such as Hsiao Li-jun and Rong Fang-jie, structures in Taiwan are often replicative, reified versions of foreign architectural styles. One particularly blatant example is Tsai Yi-cheng’s Chimei Museum in Tainan – a building whose neoclassical architecture goes so far as to incorporate a replica of Jean-Baptiste Tuby’s Fountain of Apollo from Versailles.

Given that a grand debut may never take place, TPAC will be rolled out in a more gradualist fashion: even if TPAC aims for international recognition and to host international performances, its debut has occurred during the Covid-19 pandemic. As such, views of its success will be contingent upon its ability to transform itself into a trusted institution and a natural part of Taipei’s urban fabric, rather than existing as an alien spaceship plopped onto the city by politicians hoping to make a name for themselves. Only time will tell whether this can be accomplished.

Words Brian Hioe

Photographs Tei Koukei

This article was originally published in Disegno #33. To buy the issue, or subscribe to the journal, please visit the online shop.