Good Road, Bad Road

Image courtesy of Beeline.

About three times a week, on a good week, I cycle to work. I should cycle more. Door to door it’s my quickest route, it’s better for my health, and has that added edge of worthiness associated with cyclists.

The route itself is inviting too – an unbroken path following the Regent’s Canal north from Limehouse towards Haggerston in London’s east. At points, it even borders on the pastoral. Over the course of a year, blossoms are succeeded by leafy greens, to various reds, bronzes and coppers of canal vegetation. There are ducklings swimming amongst dumped Lime bikes, dreamily streaming with reeds.

A user selects a fast route on their phone, which is paired to Velo 2 (image courtesy of Beeline).

During my old route to work – the “bad route” – I had to sit behind Mile End traffic for minutes on end, gradually ingesting fumes from a bus I’d be too worried to overtake lest I be crushed in its blind spot. I’d awkwardly circumnavigate the Victoria Park roundabout via multiple zebra crossings. Shamefully, it scared me to cycle around it. I’m a fussy cyclist. I had always avoided the canal route for similar reasons. In all honesty, unless I can cycle on a completely separated cycle lane I’m probably not having a great time. In the case of the canal, I was keenly aware of the imminent risk of veering off the narrow path and drowning a horrible death amongst all those sunken, reedy Lime bikes.[1]

I was pleasantly surprised, then, to discover how easy cycling up the canal was when I finally decided to embark upon it. I took it slow, preferring to hover behind people and overtake with plenty of space. On finishing, I was intrigued to see my smart watch displaying the total time as 22mins, a vast improvement on my previous times via roads. I’ve since theorised that, due to the lack of traffic lights, junctions and/or need to weave around stationary traffic, it’s much faster. Because of this, the canal has become a pretty good motivator for me to cycle more.

Beeline hopes that users of Velo 2 will regularly rate routes, growing the data set upon which the device is built (image courtesy of Beeline).

The canal is the route I have in mind as I find myself opening Velo 2 on an autumn morning. Manufactured by Beeline, the Velo 2 is a black, circular screen, just under 50mm across and 20mm deep (it’s almost identical in size to my smart watch, which strays large). Beeline designs wayfinding hardware and software for bicycles and motorbikes, and Velo 2 is its most recent product for cyclists. It’s a simple device that provides directions to help cyclists navigate, saving them from attaching their phone to their handlebars (or keeping it in their pocket with Google maps blaring, or else having to stop every five minutes to check their phone for the route – it always comes back to the phone). “The size really matters to people,” Sam Lucas, Beeline’s head of design, tells me. “I think the fact that you can put the Velo 2 in a pocket, and not really worry about it is a big draw.” The device attaches to your bike via a discrete mount that straps onto the handle bars using black elastic bands. Once the mount is set, the Velo 2 itself can be twisted on and off. It offers obvious ease and flexibility for someone like me who regularly takes short trips and parks my bike outside.[2] In terms of set up, the device is operated by a smartphone app, and connects with the seamlessness that consumers now expect from any kind of technology product. I add in two favourite places as “saved locations” on the app: my current one (home) and work (Rose Lipman Building). It’s morning and I’m about to test it on my ride to work. Beeline offers me three route options – fast, balanced, quiet – but none of these are my usual commute to work. That puzzles me.

“The initial idea was, ‘Why don’t we make a really nice looking compass to go on your bike so you can orient yourself in the city?’” says Mark Jenner, who co-founded Beeline with Tom Putnam in 2015. “From there it developed into: ‘What if, rather than pointing north, the compass pointed at your destination? So you could find your way through the streets?’” Jenner and Putnam wanted to strip back some of the complications of cycling around a city and tap into the sense of joy they found in meandering about on a bike. The first Beeline product, 2015’s Velo, stayed true to the compass idea: a bike-mounted navigation device that displayed an arrow continually shifting to point the rider in the direction of travel. Jenner and Putnam wanted to offer something simpler, more intuitive and less intense than the more detailed bike navigation tools out there. “There’s lots of tech that is designed for elite sport cyclists – the sort of people who go for long rides on the weekend,” Jenner explains. “There’s not a huge amount catering for the person who is new to cycling, or someone who literally just rides their bike to work on known routes, and never goes off of that.” I feel a twinge of self-recognition as to the latter camp.

Beeline’s screen sits above a four-way rocker button in order to maximise its size (image courtesy of Beeline).

Meeting this gap in the market, the first Velo found a dedicated fan base whom Beeline courted and kept in contact with to understand how they experienced the product. As time went on, however, a sticking point began to emerge for some users. “Conceptually, the arrow is a really fun idea,” Lucas says, “but for a lot of use cases, like if you’re trying to get somewhere by a given time, it’s frustrating.” Velo 2 is the company’s answer to these frustrations. In this updated model, the device’s user interface has moved away from the compass-only wayfinding system (although it does retain this option if desired). Velo 2 now provides step-by-step directions, but aims to retain the spirit of simplicity of its predecessor.

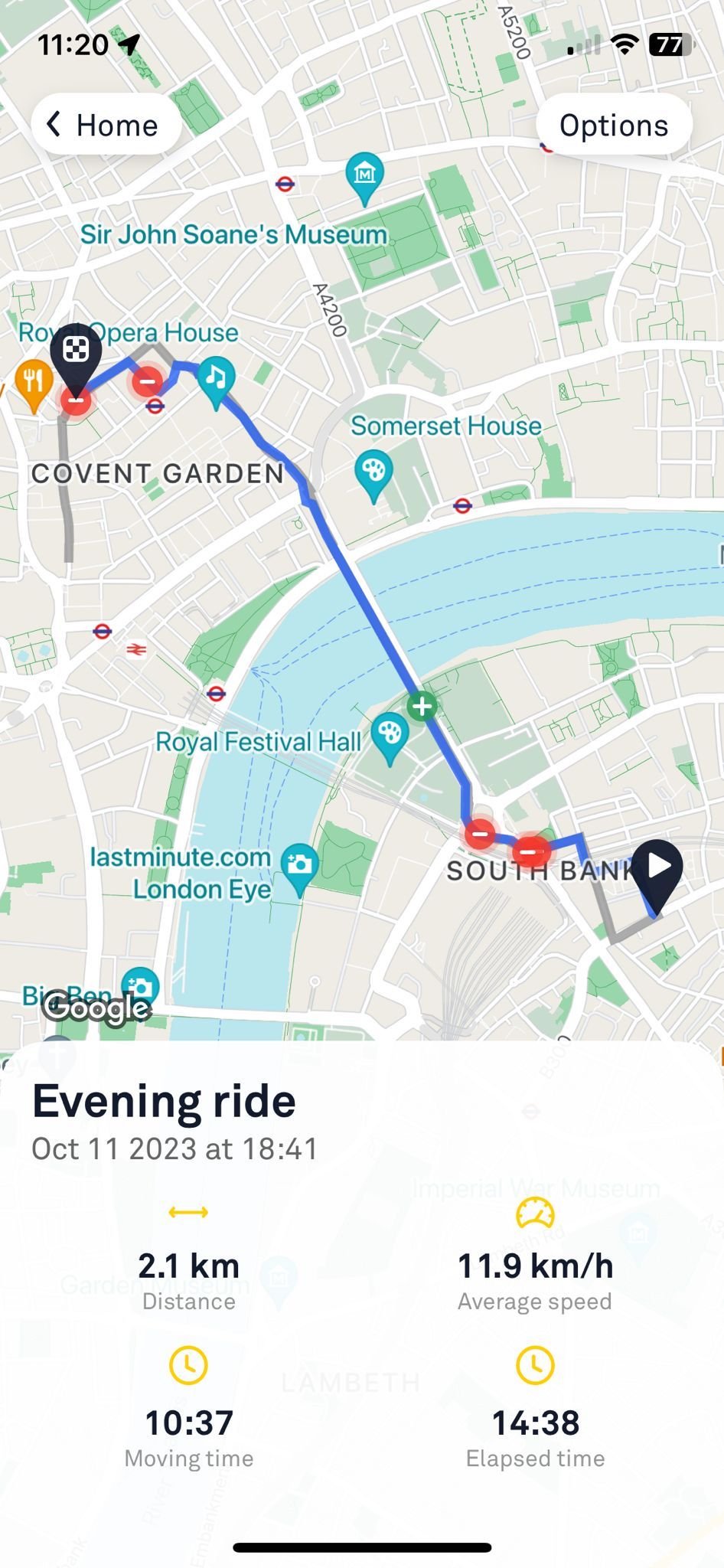

I’m running short on time, so set the Beeline app running but opt to follow my usual commute to work. As I cycle up the canal, I start wondering whether I just need to introduce Velo 2 to my route. Yet throughout the trip, the device is gently trying to pull me away from the towpath and onto a parallel route through Mile End Park. It does this by showing the path I’m on, but pairing this with a little white arrow pointing in the direction I should be heading. Meanwhile, it’s marking out the path it thinks I should be on by blocking it out in white, with other potential routes shown through white outlines. I ignore its suggestions and get to work on time via my usual route. My second journey that day is more successful: a long stretch from Haggerston to South Kensington. The fast route tells me it will take 55mins and the quiet route 1hr and 1min. I choose fast. The arrow appears on screen with the road to follow blocked out in white. It also beeps: one beep when you approach 100m to 90m from your turn, two beeps when it’s time to turn.

“There’s lots of tech that is designed for elite sport cyclists – the sort of people who go for long rides on the weekend. There’s not a huge amount catering for the person who is new to cycling, or someone who literally just rides their bike to work on known routes, and never goes off of that.”

Velo 2 guides me above central London, through Islington, Angel and Clerkenwell. My usual method for travelling is to go direct to the river, which offers a safe reference by which I navigate; as long as I know where I am in relation to the Thames, I feel fairly confident about improvising a route. There’s something instinctual about that form of wayfinding – honing in on a water source like some kind of migratory bird. Another reason I default to the Thames is because of the separated cycle lane that runs along the river, which avoids contact with cars and buses. Yet the routes Velo 2 is suggesting are not dedicated cycle paths (although they do propose these where appropriate), but rather quietways: residential streets that have been identified as seeing less traffic, and which the London Cycling Design Standards (LCDS) describes as being “aimed at new cyclists who want a safe, unthreatening experience.” Perhaps I should have been using quietways all along. In my mind, residential streets had equated to cars becoming irate as they struggled to pass you, or doors suddenly flying open from parked vehicles. But the quietways Velo 2 is taking me down feel direct, little used and visually interesting. I get distracted by strange buildings, diminutive parks and curious shops I haven’t seen before. There are moments of delight as, Oh! You’ve sprung up onto a road you recognise that leads from Old Street to Angel, but shot across it onto a hidden cut through which you’ve never spotted before.

I like this first long route, and I tell Beeline so at the end of my cycle (an app prompt appears when you’ve finished, asking you to rate the route via various degrees of smiley face). Ratings are important to Beeline. The brand wants users’ feedback and it wants as much of it as possible, because riders’ ratings are collected and combined with data from other sources to determine Beeline’s route suggestions. “The routes are based on things like time, historic traffic information and whole realms data from OpenStreetMaps,” Lucas tells me. “Then we can plug the user’s data in and use machine learning to expand that very quickly.” Suggestions evolve over time as more and more users have their say on whether or not they like a route. “I think the feeling that the product is living is one of the things that is so interesting about it.”

Velo 2 suggests routes with residential streets that experience less traffic (image courtesy of Beeline).

The Velo 2’s hardware design has been adapted from its predecessor with this feedback in mind. Its black glass circular screen offers an initial moment of cognitive dissonance as you grapple with the fact that it’s not a touchscreen. Instead, a four-way rocker button is situated below its screen, with the user pressing down on the sides of the circle in order to use it – it took me slightly longer to realise this than I’m willing to admit.

The arrangement of these buttons has visual similarities to the original compass inspiration. Four points are arranged on the screen; the north and south are marked out by white dashes, indicating the buttons that allow the user to switch between information screens: battery status or remaining route travel time, for instance. The east-west lines are green and red dashes respectively, the universal colours of yes/no, good/bad, stop/go. If you dislike a particular road that you are cycling down, just press red for a moment or two: a fat sad-face appears on the screen. Like the road you’re on? Press green and a smiley face affirms your evaluation. This rating mechanisms is key to the Velo 2. “We want people to be liberal with feedback,” says Jenner.

Propelling the green/red rating system to the front of a very minimal piece of technology highlights the importance of the rating system. It’s appealing to rate whilst cycling and there’s a satisfying dopamine kick as a circle loads up around the screen and completes when a qualitative smiley face appears in its centre (this “loading up” system is also designed to reduce any accidental ratings that might occur from bashing the Velo 2 in passing). Industrial designer Jon Marshall, who worked on the original Velo, was invited back to design the hardware for Velo 2, and this emphasis on feedback was central to the whole process. “When we started the project, we knew how important the buttons and the rating systems were going to be,” he says. “So we mocked up some models. They weren’t functional, just bits of cardboard to investigate that voting process. We realised pretty quickly that the bigger the button, the smaller the screen. We couldn’t square the circle of that issue for ages, until we came up with this idea of the upside-down construction.” Placing a rocker button below its screen allowed Beeline to keep its discreet size, but with as large a display as possible.

“What puts you off navigating by bike? I find solace in the fact that there are so many things that people dislike when cycling, particularly as they’re often things that I feel I’m being a bit wimpish or high maintenance about.”

There are obvious advantages to this system. For example, when attempting to approach the Waterloo IMAX roundabout, I find myself being rained on heavily and wearing gloves. The analogue button system succeeds where a phone’s touchscreen would fail given rain and fabric-laden fingers. I duly and negatively rate the road I’m on as red – bad road! – following a confusing and traffic-heavy right-hand turn. The roundabout, however, leads me directly onto Waterloo Bridge, which I immediately rate as green. Lovely view! Good road! It strikes me afterwards that this might be unfair to Beeline (after all, access to the bridge can only be reached via said roundabout), but the act of rating

has become habituated in me over the course of my test runs. It’s something Marshall also touches on when I speak to him. “Initially whilst I was trialling it, I was thinking: what am I actually rating here?” he tells me. “Is it the comfort, the speed? I had to get the hang of thinking, no, it’s just an instinctive plus or minus, thumbs up, thumbs down, and then allowing the wisdom of the crowd combined with Beeline’s AI model to make sense of it.”

This idea of creating a big data set driven by human users resonates more widely than just Velo 2’s user base. The original research behind the product was made possible by a European Space Agency (ESA) grant: the ESA’s interests, it would seem, are not solely interstellar, but also extend to terrestrial wayfinding. ESA is interested in how people make choices to navigate spaces on mass and sees this collective thinking as an effective computer to calculate tradeoffs in wayfinding around a complex space like a city. “The Beeline project aims at demonstrating a safest routing and mapping service optimised for the needs of cyclists in order to encourage people to choose to cycle,” ESA states loftily on its sustainable development goals’ website. “The way in which the proposed system adds value is in the manner in which it combines all of these various space assets to be able to mimic human intelligence by weighting them in the correct manner.”

An example of a Beeline route with rated sections (image courtesy of Evi Hall).

What puts you off navigating by bike? I find solace in the fact that there are so many things that people dislike when cycling, particularly as they’re often things that I feel I’m being a bit wimpish or high maintenance about. Being next to cars. Having to wait at traffic lights. Turning right. Other cyclists. Being next to parked cars. Hills. They’re things we feel we ought be better or braver about than we actually are. These moments of hesitation are echoed in design handbooks for planners of cycling infrastructure. The LCDS for example, notes that “right turns in traffic, which require cyclists to filter into the middle of other vehicles, should be avoided wherever possible”. In a similar vein, queued up traffic is listed as one of the “Sources of Stress” in the Urban Bikeway Design Guide from the North American National Association of City Transportation Officials. “Motor vehicle congestion presents safety and comfort issues for people bicycling,” it declares. “Queuing encourages both motorists and bicyclists to engage in unpredictable movements.”

Beeline is interested in the tradeoffs we make when navigating cities, and London is a great case study for this. It’s a complex, old and winding city, creating a continually expanding web of varied route options and combinations. “There’s always a balancing act when cycling between whatever your preferences are for the route and how quickly you want to get there,” says Jenner of the considerations they balance to create routes. “You’re always trading off between the two. So for a quiet route, your journey might be 50 per cent longer, but it will be roads that you’ll be comfortable with: they’re quieter, residential or have segregated cycle paths.” Beeline’s routes aren’t perfect: you’re not going to have a perfectly safe, quiet cycle every time. Where an area on a route has been badly rated but is unavoidable, that area is marked in orange, forewarning you of what’s to come. I don’t know if this ultimately makes me feel more confident when cycling – after all, you can’t see the orange line on the Velo 2 as you cycle, only in the app view of the route – but at least I have a sense of what I’m getting into. I think it boils down to what kind of person you are. Do you want constant information about a space to feel safe and prepared, or would you rather not worry unnecessarily about things you can’t control?

Image courtesy of Beeline.

“We want people to rate in a way that’s more about their emotional reactions than whether there is a pothole,” Lucas enthuses, expanding on Beeline’s attitude toward rating. More ratings means better routes, so much so that Beeline offers its app for free, regardless of whether you pair it with its Velo devices. The drawback of not having a paid-for customer is weighed against being able to collect more road ratings and also meet some of Beeline’s guiding principles of making cycling more accessible to more people. The popularity of these routes amongst Beeline’s users means there are now plans to begin offering in-app subscription services that move beyond travelling from A to B, and instead create routes that last for a set time, or which cover a particular distance before looping back to their starting point. As such, any and all influences are fair game in terms of how you decide to rate a route: how pretty the road is; how safe it feels; how well paved or not it is; how quick; how noisy. But if Beeline is so keen for rampant ratings of roads based on any and all criteria, it makes me doubly wonder why my route up the canal isn’t an option. I put this to Lucas, confused, since this shortcut ought to represent exactly the kind of secret insider knowledge that Beeline wants to track and use. “We used to [include] canals and towpaths,” he tells me, “but we removed them based on user feedback and rates.”

Canals, it turns out, are unpopular because “they’re incredibly dependent on the time of day,” Lucas explains. “At peak times they can be pretty sketchy because there’s lots of foot traffic, and at night they are very dangerous. We specifically removed them based on this.” I nod along, slightly unconvinced. You just have to be like me, I think to myself. One of the good ones who doesn’t hare down the towpath or aggressively overtake prams. With the clocks about to change, I concede that he may have a point about the darkness, but still, whilst the weather is good I’m sticking to my shortcut.

“We want people to rate in a way that’s more about their emotional reactions than whether there is a pothole. ”

I’m on my way to work as usual up the canal. I wouldn’t say I’m rushing or running late, but I am making progress.[3] I give way to runners and prams and merrily ting my bell before pedalling under bridges. I approach a corner, about to pass under a long bridge just before Broadway Market, tinging away. It’s busy on the towpath today but I’m clear. Or so I think until another bike appears silently but at significant speed from around the corner. I slam the breaks on, my bike stops, I don’t. Crashing into the wall of the bridge with an outstretched arm, I culminate the indignity by lying intertwined with my bike on the towpath with my arm cradled across my chest. My elbow hurts and I’m bewildered. People are gathered around me, including my crash-ee, a man with salt-and-pepper hair on a green Lime bike. My bike is bashed up and I’m feeling shaken and a bit guilty. Overall, however, I’m OK and eventually I walk my bike away shamefully to somewhere I can lock it up.

I finish my journey on foot. Walking along the towpath, I’m twitchy, turning around to watch out for bikes passing me, peering round bridges before walking through them. My good route has morphed into a bad route. Red. Sad face.

I reflect on what the Beeline team think about the confidence someone has on a bike. Lucas sums it up when explaining why rating is so important for them: “One scary moment or one negative moment ruins the whole ride, so it matters to us that we can remove that for as many people as possible.” It’s true. I’ve not been up or down the canal since my crash. Not just because it’s now dark in the evenings, an immediate barrier both visually and psychologically, but because the whole route has been recast in my mind. It’s become a no-go zone in my mental map of London, sat alongside locations such as Commercial Road with its never-ending supply of buses, the melee that is Hyde Park Corner, or anywhere in Marylebone.[4]

“One scary moment or one negative moment ruins the whole ride, so it matters to us that we can remove that for as many people as possible.”

In the meantime, I’m experimenting more with Beeline on a few different routes to and from work. I’ve accepted that it takes longer, that I’ll have to get up earlier, and need to cycle further. Much like the routing options, I’ve sacrificed time for safety. It’s not all bad. I’ve seen Halloween decorations go up, leaves mature and fall, and Christmas decorations start to creep over the more enthusiastic houses like so many LED vines. My routes now have a couple of steeper sections, which I grudgingly concede is better for me. They’re smoother too, with fewer potholes and tree branches to navigate. Arguably, I pass by more useful things on my journeys, such as shops, post offices and pubs. It’s added time, but they’re not bad journeys. In fact I’ve been enjoying them. Perhaps that’s what it’s really all about.

[1] Other dumped e-bikes are available.

[2] In hindsight, perhaps too easy. I’ve now lost two of the four bands by accidentally slingshotting them into moving traffic whilst attaching the Velo 2 to my bike.

[3] A phrase my driving instructor would use – “You’ve got to make progress!” – when I was driving too slow. She said it a lot.

[4] Where drivers honk at me every time I’m there on my bike. I’ve come to assume it’s due to the sin of “being on the road”.

Words Evi Hall

This article was originally published in Design Reviewed #3. To buy the issue, or subscribe to the journal, please visit the online shop.