A Topography for Encounter

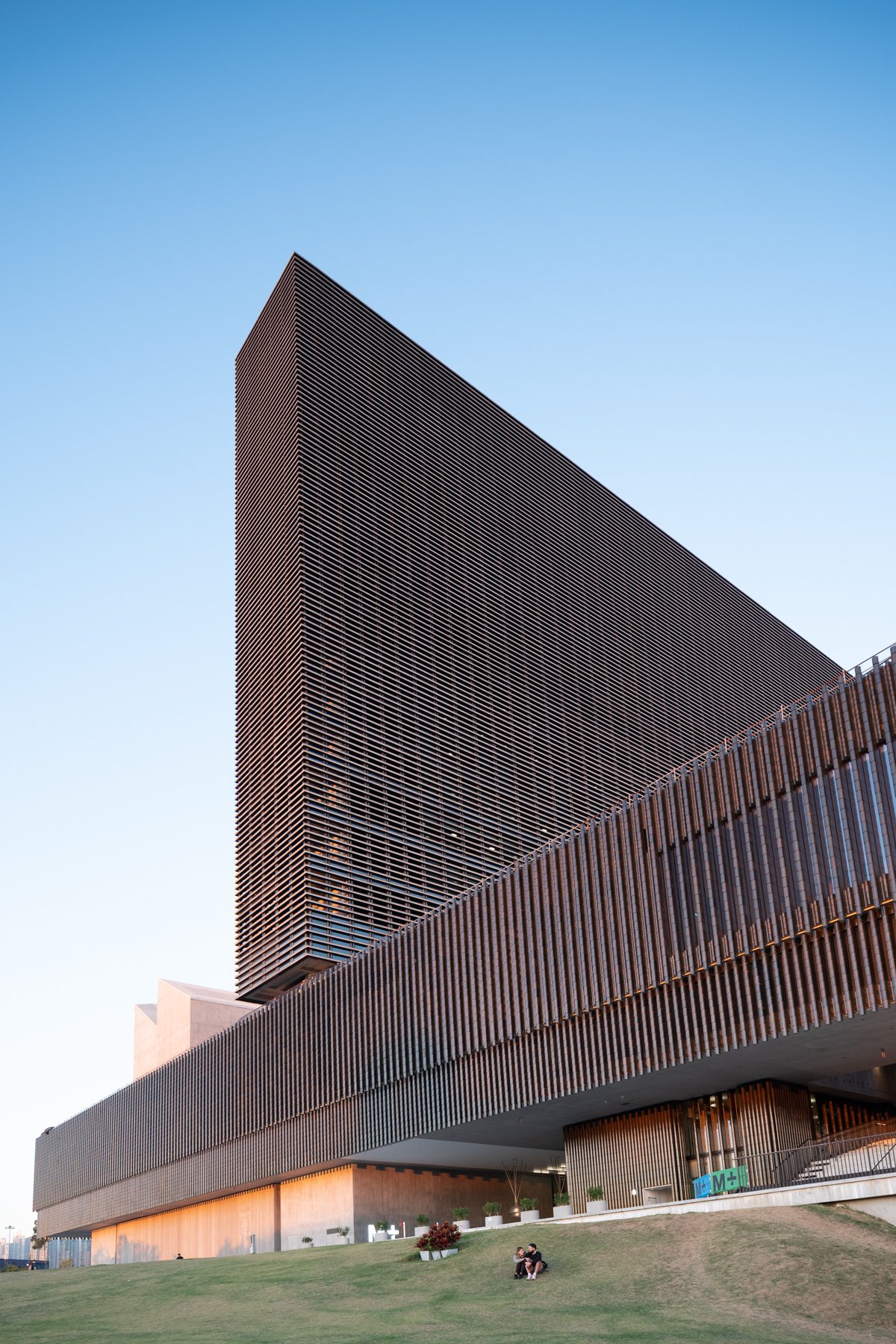

M+ in Hong Kong by Herzog & de Meuron (photo: Bowy Chan).

Growing up in Hong Kong in the late 1990s, I have a vague memory of boats carrying earth to fill in the harbour. I remember a different coastline and skyline, a different airport. Later, we started calling this newly made land West Kowloon, an addition to the southern part of the Kowloon peninsula that faces the Hong Kong island.

West Kowloon was developed as part of the city’s Airport Core Programme, a HK$160.2bn series of infrastructure projects focused around the new Hong Kong International Airport. Today, however, its reclaimed land is being put to different use. At the western end of West Kowloon is M+, a new cultural centre for 20th and 21st-century visual art, design and architecture, and the moving image, designed by Herzog & de Meuron (H&dM). It is one of the focal points of the ongoing West Kowloon Cultural District (WKCD), a government-backed development for the district masterplanned by Foster + Partners that comprises 16 arts and culture venues, a water-front park, a few skyscrapers, and a high-speed rail station that connects Hong Kong to Beijing.

In 2013, H&dM (in partnership with TFP Farrells and Arup) won the international competition for the M+ building, which comprises 17,000sqm of exhibition spaces, spread across 33 galleries. At the same time as H&dM worked on its architecture, the museum began building its collection. Reacting to Hong Kong and East Asia’s fast-evolving culture, M+ positions itself as a new kind of multidisciplinary institution dedicated to global visual culture: its collections, it says, “are rooted in Asia but defined, developed, and examined from a global perspective”. Other than visual arts, M+ also collects and showcases moving image works, design objects, architectural projects and everyday material culture from Hong Kong, Mainland China and beyond. In M+, one can find works as wide-ranging as Zhang Xiaogang’s well-known Big Family painting, Archigram drawings, Samson Young’s performance of Muted Tchaikovsky’s 5th, Sony’s robot dog AIBO, and a plastic ball manufactured in Hong Kong in the late 1950s. It is a breadth, and curatorial framework set outside the hitherto dominant perspectives of North America and Europe, that hopes to set M+ apart from the leading art museums of the global north.

Shiro Kuramata, Ishimaru Kiyotomo sushi bar (1988).

After eight years and multiple delays, M+ is now complete and open to the public. The project has seen H&dM grapple with the undefined and the unfamiliar. A venue for contemporary visual culture is new to Hong Kong – we have never before had a modern or contemporary art museum. Yet while M+ highlights arts and cultural programmes previously underappreciated within the city, it is also a building type that we Hongkongers know well: a tower with a podium.

“M+ is not only a museum for contemporary art and modern art; as the name implies, it’s a museum for visual culture.”

During the day, M+ stands out amidst Hong Kong’s skyline, which is mostly comprised of glass skyscrapers, thanks to its contrasting dark-green ceramic facade. At night, the south facade of the tower turns into a “welcome” sign, with an integrated LED screen advertising the presence of M+. Up close, you realise that the elevated podium doubles as a platform, a public space that is open to all sides and which exists on multiple different levels. Visitors can travel up to the main galleries in the podium, or pass under into the industrial spaces below. A grand stairway – an element previously employed by H&dM at its 2016 Switch House extension of London’s Tate Modern – serves as a link between the museum’s entrance, its hovering podium, and underground cinema space.

The tower, meanwhile, houses the institution’s research and administrative departments – functions that are traditionally hidden away in back-of-house areas, but which here are intended to remain partially open. In Hong Kong, the adaptation of the museum into the podium tower has allowed H&dM to carry forward its experimentation in verticality in museums, also seen in the Switch House extension.

Liang Shuo, Urban Peasants (1999–2000).

Underpinning all of this is the Found Space, a subterranean gallery for rotating installations that was carved out when the architects excavated around a pre-existing underground tunnel for Hong Kong’s Airport Express. This existing infrastructure had initially been seen as an obstacle that would complicate planning for the museum, but to H&dM it quickly become its raison d’être: an opportunity to look for what lies beneath the ever-changing land and sea of Hong Kong. Before the harbour was filled in the 1990s, the dockland surrounding what later became West Kowloon was variously used for factories, a fire station, and a camp for Vietnamese refugees entering Hong Kong by boats. Before that, it served as a military dock for the British Navy, where they made torpedoes.

These are just part of the complex, yet often obscured history of Hong Kong. Today, Hong Kong’s future is again at a crossroads. There are growing concerns about the erosion of freedom of expression and the public realm in Hong Kong, in particular after the implementation of the National Security Law in June 2020 that reduced Hong Kong’s judicial autonomy. Alongside ongoing travel restrictions caused by Covid-19, fears about censorship and oppression have left their mark on M+’s opening. In September 2021, images of the works of Ai Weiwei, including a photo of the artist raising a middle finger in Tian’anmen Square, have been removed from M+’s webpage. More works by Ai and other political pieces acquired by M+ are currently “under review.” “The ‘national security law’ that China’s central government passed last year has ruined the local political environment almost overnight,” wrote Ai for Artnet, “and has left the Chinese government’s promise of ‘one country, two systems’ as mere waste paper.” In this context, questions over what role architecture can play in facilitating artistic and creative freedom emerge.

With these issues lurking in the background, I spoke to Wim Walschap, the partner-in-charge, and Ascan Mergenthaler, a senior partner at H&dM. Over the course of our conversation, we were drawn inexorably to a question that sits at the heart of M+, and which the architects themselves asked upon winning the commission back in 2013: “What can lend authenticity to reclaimed land?”

Wang Wei, 1/30th of a Second Underwater (1999).

Juliana Kei I studied architecture as an undergraduate at the University of Hong Kong, and I remember going to the early presentations for the WKCD. It’s nice to see that M+ is now complete, and I suspect that many people in Hong Kong will probably feel the same way: “Finally. We have our very long overdue contemporary and modern art museum.” So I wanted to go back to the beginning, because the commission for the project actually came before the museum’s collection had been assembled. It also came at a time when the notion of East Asian art, or even East Asian modern art, remained relatively undefined.

Ascan Mergenthaler It was a special competition and I think that helped us develop the design. It was not the kind of competition where teams were invited to develop a design without any exchange with and context from the client. Instead, they invited six teams to not only compete, but also to come to Hong Kong for workshops. We basically tested a client dialogue with them during that competition process, which was a powerful tool for all of us to understand the common goals and aims of this project. That made our competition proposal so much stronger, because we had the opportunity to test ideas and understand a little bit better what they needed. Because M+ is not only a museum for contemporary art and modern art; as the name implies, it’s a museum for visual culture. That was interesting for us, because it makes it a much richer experience – it’s not only about white cube galleries, because it needs other, very specific, spaces as well, such as a cinema and multimedia lounges. There is also the Found Space, which can be used for art, but also for architecture, design, or even moving image performances, audio visual works – all kinds of things. That ultimately makes everything so rich, because it’s really a building for cultural activity of all kinds.

Wim Walschap And while it’s correct to say that the actual collection was not yet there at the time of the competition, there had already been Uli Sigg’s donation, which was an important start [Sigg is a Swiss art collector who holds the largest private collector of contemporary Chinese art in the world. In 2012, he donated a portion of his collection to M+, which now encompasses 1,510 works of Chinese art from 1972 to 2012, ed.]. Even during the competition we were able to do some planning with a curator who knows that collection well. So it wasn’t that there was absolutely nothing to start from.

Fang Lijun, 1995.2 (1995).

Juliana And did anything change over the years as the collection grew? Did the museum’s needs change?

Wim Not much. I don’t think we ever had to change the design because of a certain piece. What I do remember, however,is that they had to re-check the loads on the podium roof, for example, because they had a huge sculpture which they wanted to mount on the building. Things like that happened, but in a very limited way.

Ascan There were almost two parallel work streams. We were working with them on the refinement of the different exhibitions in the display spaces we were developing, while they were simultaneously building up the collection. There were some items, of course, that they were very excited about. They shared the news with us, for instance, when they bought the sushi bar from Japan [Shiro Kuramata’s 1988 interior for Tokyo’s Kiyotomo restaurant, which represents Kuramata’s last extant work of interior design, ed.], but even that did not have a direct impact on the planning and they were able to accommodate it within the space. That’s the strength of the building: it allows for flexibility. Spaces are not tailored around one piece.

Juliana Was this experience on M+ similar to any of your other museum projects from around the world?

Ascan Some of it was similar and some goes a little beyond what we have done before in museums. It was important to consider the moving image, for example, so we have three cinemas in this building. The Found Space, meanwhile, is an extreme example of something we’re always looking for in our work. Is there anything we can dig out? Is there something on the site that we can use as a first creative input, or something we can rub shoulders against to develop something? Reclaimed land can be difficult because it’s just flat and there’s no context whatsoever: that’s always a challenge for us because we like things we can react to. So that’s why we were very happy when they pointed out this Airport Express tunnel to us as an obstacle, because we could actually turn it into a really positive thing for the building. The method is not so dissimilar to Tate Modern, which was also a project that was almost archeology: you’re looking for these found spaces.

Juliana And this focus on context is something you’ve worked with in Hong Kong before. The Tai Kwun Centre for Heritage & Arts is a cultural space that you finished in 2018, for example, which was created in a compound formed from Hong Kong’s former Central Police Station, Central Magistracy and Victoria Prison.

Ascan Yes, Tai Kwun is a little bit similar in that we carefully analysed the existing urban fabric to see where we could open up and make new connections. It was a very thorough analysis of what was there, and then a case of activating those found spaces and making them accessible. In that regard the method was pretty much the same, but the result was unexpected and very different one from any buildings that we have done before.

Juliana Tai Kwun is quite a different context with all its alleyways and the existing courtyard spaces, whereas one of the key design elements for M+ is its public forum, which underpins the entrance into the building. Hong Kong is a place that has interesting manifestations of public spaces. A lot of people in Hong Kong treat shopping malls or privatised spaces as public spaces. People in Hong Kong are used to walking around the atrium spaces of malls like The Element, which is so big that it’s divided into five zones, or moving between the network of buildings that connects the harbor and hills. There is also the well-known entrance plaza of the HSBC building, designed by Norman Foster. How you envision that public forum of M+ functioning in Hong Kong and within the context of a museum?

Wim We elevated the volume and freed the ground floor up as much as possible, giving the possibility for permeability and access from all sides on both the ground floor and at the waterfront level. This is a public area both inside and out, and it’s a social space for people. Of course, you can go further into the museum, but you can also just stay there and have a coffee or meet people. It has a relation to what you see in the shopping malls, but it’s a very different space and not one focused on commercial activities. It can be a space where you just hang out and it even has an extension on the roof. From that ground floor, you can go all the way up to the roof garden on top of the podium. That is supposed to be a public space, which is accessible 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

Ascan It’s a platform for exchange and for supporting encounters between people and art, and also just between people. That was absolutely key, because there are only a few cultural buildings in Hong Kong right now, and they tend to be very closed. They’re hermetic structures with one front door, and it’s not so easy to go inside – there’s a physical and a psychological barrier to making that step. It was important that we send a very different message: “Please come in.” Just come under the roof to be sheltered from the sun and rain, and then you’re invited to go further and discover things. You’re invited to discover the Found Space. You’re invited to look up through the slots and discover the gallery level and the tower above. These vertical moments, which are almost like a section through the entire building, were actually important for us to make accessible and easy to engage with. That’s a huge opportunity, because cultural activities in Hong Kong have so far been a little bit elitist. The hope with M+ is that it will invite in more people and spark interest in different levels of society. And that’s not only the architecture, it’s also the programme.

Wim There’s choice.

Kongkee, Flower in the Mirror (2021).

Ascan Maybe its easier for people to immediately relate to popular culture or movies or design, but then they’ll also look around the corner and discover the art collection and the ink drawings and everything else they have there. It’s going to be so rich in terms of materials. There is also the tower facade, which we animated with embedded LED strips. That not only anchors the building in this very typical Hong Kong skyline, but it’s also a kind of billboard. It’s an artistic message from the curators or the artists. You’re almost inviting people from Hong Kong Island to come over to Kowloon. It’s way of sending out a message to the people of Hong Kong: “Please come and visit us. Here is something of interest for you.”

Wim It’s the endpoint, insofar as from the ground floor you can go up to that roof garden where you actually have that screen, and it’s so close by – you can almost physically touch it. Also in the materiality, there is no break between the outside and inside of the public space. The treatment of the floors, the ceilings, the cladding on the different walls is the same. So that also helps to invite people in and not create any kind of threshold between inside and outside.

Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries, Crucified TVs — Not A Prayer In Heaven (2021).

Juliana In the past few years there’s been a paradigm shift in museums or centres for visual culture in terms of showing, archiving and displaying digital art and design, but also in terms of decolonisation. You’ve spoken about making the back-of-house aspect of galleries and museums more visible to encourage participation – is that how you see architecture’s role in the changing paradigm of museums and galleries?

Ascan I mean, the big paradigm shift happened 20 years ago with the Tate Modern – not that it was the only one, but it was the most prominent example of a museum for contemporary art suddenly not only being a museum to store and show art, but also a platform for exchange and education. It was a place to invite the community into and it became a social centre of a sort, which its 5 million plus visitors per year is testament to. People just go there. They might look at an exhibition, or they might meet friends, or see a movie or a lecture or a talk, or whatever. So it’s not like we did this for the first time with M+ – we started to work on these ideas more than 20 years ago, but of course you can always add another dimension to it. In M+, this idea of learning, and the idea of exchange and encounter is very much in the foreground. It’s very prominently located on the ground floor, so it’s very accessible, but it’s also nice that you can sit on the roof, so theoretically you can have outdoor classes or impromptu learning sessions and exchanges with school classes and smaller groups. It’s literally a topography for encounter and exchange.

Lin Tianmiao, Braiding (1998).

Juliana The idea of topography is really fitting in the case of Hong Kong, which has sometimes been described as “a city without ground.” In areas like Central or Causeway Bay there are so many artificial ground levels created by sky bridges and the podiums of high-rise buildings. I think people in Hong Kong are programmed into walking between those elevated levels. On those bridges, even without street names and numbers, we still know where we are going.

Ascan It’s interesting that you mention that, because it’s definitely true. It’s simultaneously fascinating and disturbing. What I find interesting about Hong Kong’s network is that not everything is happening on street level, not everything is happening in public space. The boundaries between private and public space are so blurred, which is compelling but at the same time confusing, because sometimes you cannot immediately get down to where you want to go. You’re very restricted in your movements and the pathways are very pre-defined. Coming from Europe, it’s a little bit of a frustrating experience – like being on a highway where you can’t find the exit.

Wim And not easy to orientate.

Ascan Very difficult. That’s something we tried to do differently in Tai Kwun. You’re still on different levels there, but it’s a quite natural flow and it’s not pre-prescribed or pre-conceived how you have to navigate through that site. It’s very open and the same is true for M+. It has also these different levels, but there are so many different possibilities as to how you connect to them. Yes, you can take the escalators but you can also walk through the auditorium, you can take the stairs, an elevator. It’s very open and in that regard I think it’s very different compared to the typical built topography you find in Hong Kong.

Wim It’s not stressful. You have choice, not only in terms of content, but also how to circulate through those spaces. There’s more than one solution, more than one option.

One of M+’s gallery spaces.

Juliana Going into Tai Kwun, I’ve always found that there is a sense of, “I can stop if I want to. I don’t have to keep moving.”

Ascan Try to do that elsewhere in Hong Kong, and you’re immediately overrun. It has a different speed to it, I guess. It’s much slower, and that’s nice. It slows people down to perceive the context and the environment in a different kind of way. There are many similarities between Tai Kwun and M+, but at the same time they’re so different, not least in terms of sheer scale. It was nice that we were able to do Tai Kwun before M+, because we got to learn more about the city. It was a little bit like an incubator, starting what could later happen on a larger scale with M+. But Tai Kwun is really about being in the heart of the city, where Hong Kong is at its densest. It’s an oasis, whereas M+ sits on the edge of Kowloon on an empty piece of land. So to create a moment of density there – in a different kind of way, and maybe in terms of its content – was the aim.

Juliana And how do you do that?

Ascan One project is about revitalisation and the other is about vitalisation – injecting life into a place that was basically a wasteland. It’s about how can you create a space that doesn’t become boring or repetitive, and in which you have a lot of diversity: spatial diversity, proportional diversity, different materials, different experience in terms of how light comes into the spaces. From the outside, the building looks so simple. It’s an upside down T-shaped volume floating above the ground. But once you’re inside, you discover all these different layers and details and proportions and scales and vistas. Our aim was to create something like a city within the city, a very rich experience on something that was just an empty piece of land. I mean, this piece of land was nothing. You would not have gone there. And suddenly, everybody from Hong Kong will go there.

Juliana When we’ve talked about museums over the last few decades, the Bilbao Effect and an institution’s relationship with its city has often been at the forefront of the conversation. But in Hong Kong it’s quite different. Our city is led by global finance, it also has its relationship with tourism. It’s already a very globalised city. I wonder whether this consideration of how architecture will have a dialogue with the city’s future development or its past affect your design?

Ascan I mean, you don’t have to put Hong Kong on the map. They have a different problem to Bilbao in that they need to put culture at the heart of Hong Kong. It is there, it’s just not visible and it’s not palpable. We were in a very lucky position because through Tai Kwun we had already been able to contribute to this and make the cultural life of the city visible and accessible. And of course on a much bigger scale, we can now do that again with M+. That’s pretty unique to have the opportunity to do that twice in a city. I think that’s ultimately what Hong Kong is aiming for with this building – you put in the foreground something which has been a little bit neglected or not so obvious.

Juliana Foregrounding is interesting, because while you were building M+, everything in the WKCD has changed around you. There are a lot of different buildings that are now completing and also perhaps competing with M+ [at present, 17 different visual culture and performing arts facilities are planned for the site, ed.]. How do you see the development around WKCD and its relationship with M+?

Wim The good thing is that we are at the very end of that line of venues. We are next to the park at the very westernmost part, so it’s quite nice that we will never be in between two buildings. And in addition to that, we were also lucky to do the two buildings immediately behind the museums: the CSF, the conservation and storage facility building, and also the office tower where the West Kowloon Cultural District Authority is based. So we could already create quite a strong cluster of buildings that have a clear relation with each other. But I think our project will always stand out. I’m not worried about what will be next to it.

Ascan We were in the lucky position that the project orientates itself towards the city, towards the water, towards the harbour, towards Hong Kong Island and towards the park. And, as Wim said, we were able to create our own little urban context with these two supporting buildings. And they’re a fantastic opportunity, because often storage and conservation rooms in museums are hidden away, or somewhere in the basement, and you never see them. Here, it’s nice that on the one hand you have the place where you can see art and culture, and on the other you can see where all the exhibition prep is happening thanks to a big window that looks through into that area. I like that a lot of the ingredients that actually make a museum work are visible. The tower is the same idea in that regard. It’s primarily for the administrative functions of the museum, but rather than tucking them away and treating them as an afterthought, they’re in the foreground. These people who think and run and make this museum alive are right there, and you see how they work. And then they also connect to the city and the place.

Wim The media screen will also play a role in that. Of course, the museum building is free-standing at the moment, although there will be something next to it eventually, but even now, with these huge towers behind it, M+ stands out. The building is there, it’s present, and that will not change.

Ascan It’s an amazing opportunity for Hong Kong. The idea of the WKCD, and creating a cultural mile of theatre, of Cantonese opera, visual culture, music, all these things, is amazing. I really hope that they’ll be able to realise all these buildings. It’s an ambitious plan and if they don’t succeed in realising the rest, then it will become a little bit of an awkward situation because you will have these fragments like missing teeth. But I think the overall concept is smart: that you use the commercial buildings to financially support the cultural one.

Juliana And while M+ was still under construction, the park was really the one thing mediating the experience of going to that part of the city. The park was completed first and it drew people to see what was going on there.

Ascan It’s so important that you have significant and great, green spaces in a city, especially in a city such as Hong Kong. The masterplan is smart: condensing the buildings on one are of the site, leaving enough room for a large, active parkland on the remainder. They’ve been clever about this, because the park recently completed and made the site accessible, and so people got used to how to get there. Also, programmatically, M+ was already around organising exhibitions in the city. They built the institution at the same time as we built the building.

Wim It’s also interesting that it’s actually, at least in my experience, one of the very few locations in Hong Kong where you can get very close to the water, even though Hong Kong is at the harbour. The sea somehow always feels so far away.

Ascan Speaking about water, if we could have one last wish, it would be amazing – and we mentioned this to the client – if there could be a direct Star Ferry line to the museum with a little jetty there. That would be so beautiful. The only drawback at the moment is that it’s still not the easiest to get to, whereas a direct Star Ferry line would make it so straightforward. It would also provide a sense of arrival, because when you take the metro you will always arrive from the back. So hopefully it’s going to be realised.

Wim It was part of the masterplan, but it’s probably not coming so soon.

Juliana But it’s already been quite a long project – nine, almost ten, years. So what was the most memorable part of the process?

Wim I think that is still to come. The building is opening and will soon be populated by the people of Hong Kong, which is the moment that I was looking forward to – but we will not be part of it.

Ascan To not be able to go there for the opening is very difficult. On the other hand, it’s a building for the people of Hong Kong and it’s nice that they will be the most important people at the opening. This period is probably the first time in history where buildings are being opened without their architects present, and maybe that’s an opportunity. This is a strong sign to the community and the people of Hong Kong. “Here, this building is for you. Enjoy it.”

Words Juliana Kei

Photographs Bowy Chan

This article was originally published in Disegno #31. To buy the issue, or subscribe to the journal, please visit the online shop.