There’s Only So Far You Can Go

Charlotte Perriand on the Chaise longue basculante B 306, 1929 - Le Corbusier, P. Jeanneret, C. Perriand, 1928| image: © F.L.C. / ADAGP, Paris 2019 © ADAGP, Paris 2019 © AChP).

“When you enter the Salon d’Automne of 1929, it’s almost as though you’re stepping into your own place, you could imagine living there,” exclaims Jacques Barsac, co-curator of Charlotte Perriand: Inventing a New World, an enormous retrospective that recently opened at Paris’s Fondation Louis Vuitton to mark the 20th anniversary of the designer’s death. He’s referring to one of the show’s highlights: a meticulous recreation of the mythical modernist interior that Le Corbusier, Perriand and Pierre Jeanneret showed at the annual Parisian art event that year.

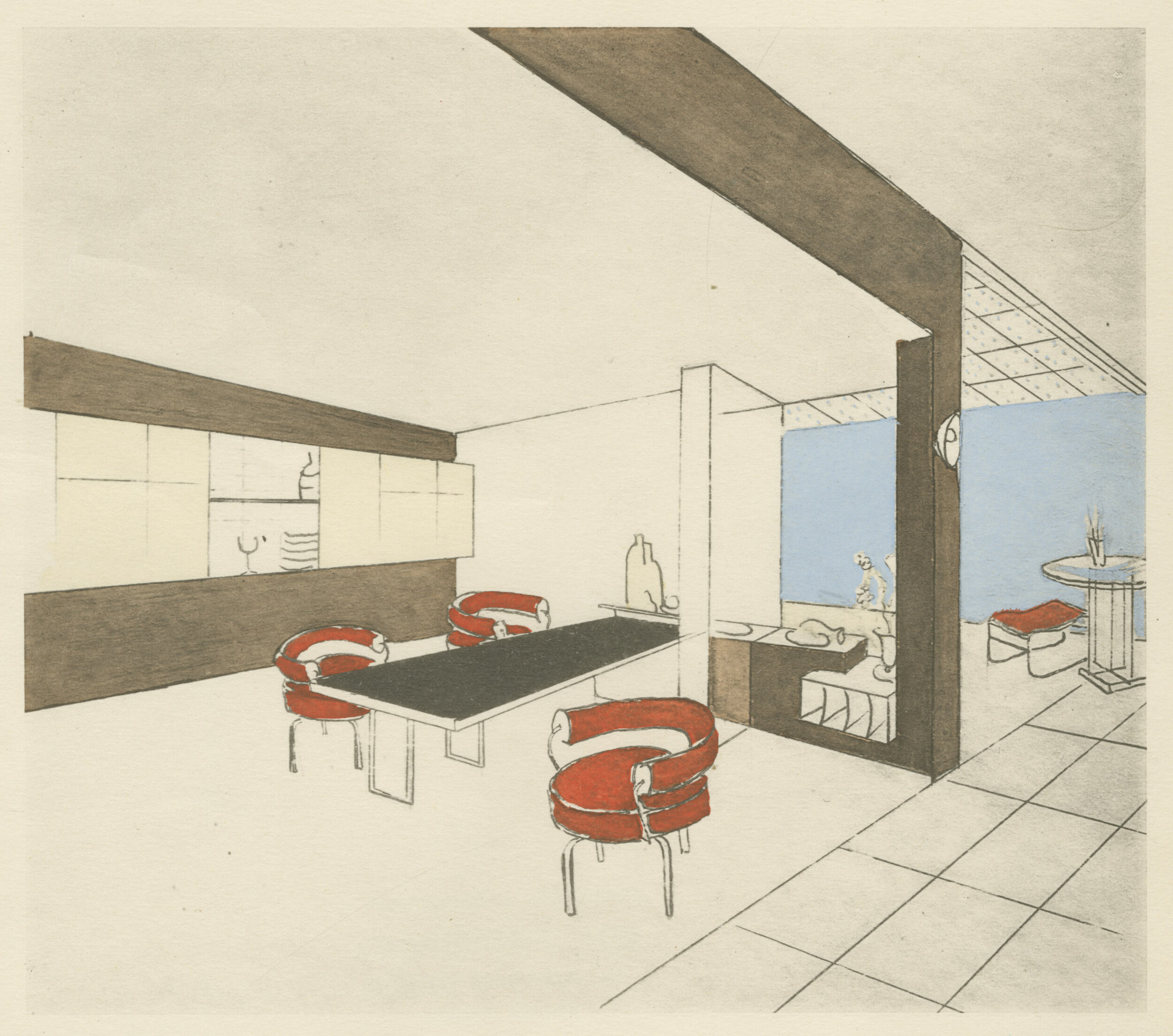

Le Corbusier was actually absent at the time – he’d departed in September 1929 for a tour of Latin America – leaving Perriand and Jeanneret to build the stand in just three months. Titled Interior Equipment of a Dwelling, the Salon d’Automne installation was a manifesto demonstration of living in the Esprit Nouveau, Le Corbusier’s vision for domestic design in the machine-age city. An idealised open-plan apartment, the stand was kitted out with the tubular-steel furniture the trio had designed for the Villa Church (1927-29) (the first time these pieces, which included the now-iconic Chaise longue basculante, were publicly exhibited). In place of walls, it featured a series of specially made metal storage units that separated the kitchen, bedroom and bathroom from the main living space. Not only was the floor of the apartment in glass, but so too was much of the external wall, which comprised one of Le Corbusier’s trademark ribbon windows set above

a parapet of Saint-Gobain Nevada glass bricks. Furthermore, the windowless bedroom, bathroom and kitchen were lit by a luminous opaline ceiling. Everywhere the eye roamed it settled on sparkling chrome, nickel, porcelain and glass, tempered only by the various pelts and hides adorning the furnishings.

Charlotte Perriand, Le Corbusier, Pierre Jeanneret – Un équipement intérieur d’une habitation - Salon d’automne 1929, Reconstitution 2019 (image: © F.L.C. / Adagp, Paris, 2019 © PJ / Adagp, Paris, 2019 © Charlotte Perriand / Adagp, Paris, 2019 Crédit photo : © Fondation Louis Vuitton / David Bordes).

The shock of the new must have been acute for those lucky few who visited the stand, which existed for a mere 12 days. Le Corbusier himself returned to Paris

too late to see it and it’s only known today thanks to the countless photographs that were taken of it – a further indicator of its modernity, since it was made deliberately photogenic for glossy magazines. “You could say it was Instagrammable before Instagram,” jokes Sébastien Cherruet, another of the show’s co-curators.

“ You could say it was Instagrammable before Instagram. ”

Allowing visitors to experience something of that shock was among the aims of the Louis Vuitton exhibition – like the salon-goers of 1929, you can walk into Interior Equipment of a Dwelling and try out the furniture. But this is merely one of the most spectacular in a range of recreations on display at the show. Running the gamut of possibilities, they include a scale model of Perriand’s never-built 1929 Travail et sport scheme (which until now existed only in the form of drawings); a recreation of her dining room as shown at the 1928 Salon d’Automne; a restitution of the Maison du jeune homme (House for a Young Man) that she, Le Corbusier and Jeanneret exhibited at the 1935 Exposition Universelle et Internationale in Brussels; one of her and Jeanneret’s Tonneau mountain refuges (a 1938 design never produced in her lifetime – the example at Vuitton was made by furniture brand Cassina in 2012); and, outside in the Fondation’s water feature, her Maison au bord de l’eau (House by the Water), designed in 1934 but only realised 79 years later by Louis Vuitton and first shown at Design Miami in 2013. Lost furniture has also been recreated for the show: the 1937 Manifesto table and 1938 Boomerang desk, for example, both designed for the newspaper editor Jean-Richard Bloch, as well as some of the giant photomontages she displayed at Paris’s 1936 Salon des Arts Ménagers and 1937 Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques.

Charlotte Perriand, Perspective du Bar et de la salle à manger de la place Saint-Sulpice, 1927 (image: © Adagp, Paris, 2019 © AChP).

“Eighty per cent of Charlotte’s work has disappeared,” declares Barsac. “Our goal is to show originals. But what do you do when you don’t have them?” For Barsac and his wife Pernette Perriand – Charlotte Perriand’s daughter and another co-curator – the designer’s work cannot be fully comprehended without some notion of its initial context. “We wanted people to understand how small her Place Saint-Sulpice atelier was,” continues Barsac, referring to the space for which the dining room she exhibited at the 1928 Salon d’Automne was created. “Why did she make that extensible dining table? Because space was at such a premium. Exhibited on its own the table seems like just a clever design object, but shown in situ its full purpose becomes evident.”

“Eighty per cent of Charlotte’s work has disappeared. Our goal is to show originals. But what do you do when you don’t have them? ”

Then there was the fact that the curators had 4,000sqm to play with – the entirety of the Fondation Louis Vuitton, which has for the first time been given over to a monographic design show. This is twice the size of, say, a Centre Pompidou temporary exhibition. As a result, there was an awful lot of space to fill and the challenge of choosing exhibits that wouldn’t exhaust visitors. Given the Fondation’s generous budgets, recreating lost interiors seemed an excellent way to communicate all the force of Perriand’s design world. Furthermore, this approach is arguably akin to Perriand’s own modus operandi, since she frequently used simulacra of idealised living as a way of promoting her work and making it palpable. In this she was following a tradition that stretched back to the emergence of the ensembliers-décorateurs in the late-19th century, all of whom exhibited at the various Parisian salons – not to mention the department stores that hired them to create new furniture lines to display in simulated interiors on their premises. Indeed, one of Perriand’s teachers at the École de l’Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs was none other than Maurice Dufrêne, a renowned ensemblier-décorateur who founded the Atelier de la Maîtrise at Galeries Lafayette. The mock- ups and restitutions at the Louis Vuitton show perfectly illustrate the power of such simulations to whet consumer desire: “When people come out of the Maison au bord de l’eau,” recounts Barsac, “they all say, ‘I want to live in a house like that!’”

La Maison au bord de l’eau, 1934, reproduction 2019 (image: © Adagp, Paris, 2019 Crédit photo : © Fondation Louis Vuitton / Marc Domage).

“What interests me in architecture and design is above all the space between objects,” explains Cherruet. “When you touch a table in metal, it’s not at all the same thing as wood. These questions of space, touch and texture are omnipresent in Charlotte Perriand’s work, so it was important to reproduce the materials and textures of these objects and to make palpable the spaces they occupied.” But how far do you go? And what about the inevitable accusations of inauthenticity? For Barsac, reproducing furniture by Perriand is legitimate to the extent that nine times out ten she designed with serial production in mind, be it industrial mass production or more limited artisanal fabrication.

Remaking the lost Bloch pieces was not only a way of illustrating the organic sensuality of her designs at a key moment in the evolution of her thinking: it also gives physical form to Perriand’s left-wing politics. Close to the communists,

she was a member of AEAR, the Association des écrivains et artistes révolutionnaires; Bloch was the editor of Ce Soir, a communist daily

that actively supported the Republicans in the 1936-39 Spanish Civil War, and the Manifesto table she designed for him featured zinc etchings of, among others, Pablo Picasso’s Songe et mensonge de Franco (Dream and Lie of Franco). So yes, this was a one-off piece, but the curators felt it was an important demonstration of Perriand’s lifelong ideal of achieving a synthesis of the arts, where fine art would be taken down from its pedestal and made an integral part of daily life. But how valid is such a reconstitution in the case of a unique table like this? Especially since the original 1930s zinc- etching technique has been lost and a modern approximation had to be found. For Cherruet, “it’s a question of atmosphere,” the justification residing in the communication of the visual and material culture of Perriand’s world.

“When you touch a table in metal, it’s not at all the same thing as wood. These questions of space, touch and texture are omnipresent in Charlotte Perriand’s work.”

When recreating whole interiors, questions of accuracy and authenticity become yet more numerous and thorny. At the Brussels Maison du jeune homme, Perriand included large expanses of Nevada glass bricks, those emblems of hygienist modernity that Pierre Chareau so famously used at the Maison de verre and which Le Corbusier also employed at the Cité de refuge and the Immeuble Clarté. Although Saint-Gobain stopped manufacturing them in the 1960s, reproductions are now available, but the problem with modern reproductions is their composition, which results in a very white, transparent glass quite unlike the green-tinged product of the 1930s. Even were you able to recreate the original composition (the specifications for which have been lost), the chances are you couldn’t use it in a public space because it wouldn’t have gone through the EU health-and-safety approval process. While reproduction Nevadas were used

to recreate the 1929 Salon d’Automne, at the Maison du jeune homme the curators came up against a further problem – those heavy blocks of glass were suspended 2m up in the air. Building a structure to support them turned out to be prohibitively expensive, so the decision was taken to evoke them using ink on backlit paper. “I now think it was a mistake,” says Pernette Perriand. “We should have faked them for 29 and used the real ones for Brussels.” Barsac disagrees: “It would have been too expensive. There’s only so far you can go. And we decided we’d invest more in 29.”

Charlotte Perriand, René Herbst, Louis Sognot – Maison du Jeune Homme, Exposition universelle de Bruxelles, 1935, reconstitution 2019 (image: © F.L.C. / Adagp, Paris, 2019 ; © Adagp, Paris, 2019 Crédit photo : © Fondation Louis Vuitton / Marc Domage).

For Arthur Rüegg, the specialist who helped the curators recreate the lost interiors, reproducing Nevada glass bricks at the Maison du jeune homme was far less important than tracking down and borrowing Fernand Léger’s 1935 canvas La Salle de culture physique – Le sport, a stylised gym in primary colours that adorned the real gym in the young man’s idealised hygienist dwelling. Rüegg’s relationship with Perriand dates back to the 1980s, when he met the designer in order to produce accurate plans of the 1929 Salon d’Automne – none of the originals had survived, only sketches, photographs and certain measurements that Perriand had noted in her logbook. Measured plans were one thing; recreating that interior 90 years later turned out to be a minefield of approximations and vexations. “Take opaline,” says Rüegg, “the opaque glass used in the storage units. It was readily available until the 1970s, but now it’s impossible to find. Opaline was coloured throughout its thickness; we couldn’t do that, so we used frosted glass to achieve a similar effect but had to etch the edges as well to ensure it looked authentic.”

“A team member spent two months sourcing fake cat fur that appeared sufficiently convincing.”

Then there was the fact that nickelled copper, which was commonly used in the 1920s, has since been banned on the grounds it emits a toxic gas. It took months to find a suitable equivalent, the team eventually settling for a slightly golden chrome. While the glass floor tiles could be reproduced, it was far too expensive to use them for the entire surface, so they have only been laid in the bedroom – which is out of bounds to the public both because of how small it is and because it doesn’t conform to today’s dimensions for wheelchair access. The living space is in linoleum instead of glass, which is also preferable from a health-and-safety perspective. The next problem was the countersunk handles in the storage units. What were their dimensions? Were they welded or not? Even once their dimensions had been “guestimated”, there was the fact that tools of the right size didn’t exist to make them and had to be specially fabricated. Where the moveable furniture was concerned, exact copies of the originals had already been made by Rüegg in partnership with Cassina, but these can’t be used in a publicly accessible display since they haven’t gone through the EU approval process – instead, visitors get to try out standard-issue Cassina reproduction pieces. And last but not least, there was the question of all the pelts and furs present in 1929. Some of them, says Rüegg, were cat and calf skin – “‘alley cats,’ as they put it at the time, while to get the very soft calf skin you probably had to kill the mother and take the calf from the womb”. Such products are still available from China, but would have been morally unacceptable in France today. The curators could have used vintage fur, but in a museum environment it has to be constantly treated and controlled for pests and fungus. Instead, a team member spent two months sourcing fake fur that appeared sufficiently convincing.

“There’s only so far you can go,” repeats Barsac. “Questions of budget and practicalities will always guide your choices.” Rather than attempt to reproduce all the bathroom fittings in porcelain, which again would have cost an arm and a leg, the curators faked them in lacquered wood. Since the washbasin was the same model used at the Villa Savoye, its form could be copied faithfully; the bathtub, however, is an invention, the photographic record being too meagre to know exactly how it looked. While in the kitchen the fridge has a mocked-up front, the Table tube d’avion in the main living space has a real glass top that attempts to reproduce the colour and texture of the original. Though Rüegg has spent years working with Cassina on this, he still isn’t satisfied with the result.

Charlotte Perriand – Maison de la Tunisie, chambre d'étudiant - Cité universitaire internationale de Paris, 1952", reconstitution 2019 (image: © Adagp, Paris, 2019 Crédit photo : © Fondation Louis Vuitton / Marc Domage).

As a simulacrum of a simulacrum, the 1929 Salon d’Automne is an impressive and photogenic fake, even if – without knowing all the problems it posed – one senses it isn’t quite right. But there were some instances where the curators gave themselves a much easier time of it, the most extreme example being their “evocation” of the Galerie Louise Leiris in Paris (Leiris was the daughter of the great Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler), which Perriand remodelled in 1989. In a gallery

of similar dimensions at the Fondation Louis Vuitton, Picasso canvasses exhibited by Leiris hang on the white walls and four Grand Confort armchairs sit in the centre of the room. And that’s it. “Charlotte’s work at the gallery produced a very pure, minimalist space, which is basically what we already had at the Fondation Louis Vuitton,” explains Cherruet. “There didn’t seem much point in going to all the trouble and expense of reproducing fake ventilation grills or any of the other detailing she designed.” To which Barsac adds: “What was important? The artworks and the visitor who observes them from the 1928 armchairs she had chosen. With that and the Fondation’s white walls, we had the essentials.” Notwithstanding this infallible logic, one can’t help feeling that, despite the presence of real Picassos, there’s something terribly emperor’s new clothes about this.

What should, in theory, have been the easiest reconstruction turned out to be just as much a minefield as all the others. Perriand designed her ephemeral Japanese tea house in 1993 for the grounds of the Unesco headquarters in Paris – her daughter Pernette Perriand remembers it well, because she worked with her mother on the project and has already recreated it once before. But for this third tea house, the conditions were a little different: while the first had stayed up

just two weeks outdoors, this one had to last four months indoors. “The minute you come inside, you have a humidity problem – it’s much drier,” explains Perriand. “There was a risk that in a drier atmosphere, over that length of time, the curved bamboo branches holding up the awning would snap. So, to avoid any problems, we made curved wooden lasts onto which we bent each bamboo branch for three months to make sure they wouldn’t budge for the duration of the exhibition.” And what about the tatamis, which are given summer and winter configurations in Japan? Pernette Perriand’s initial instinct was to arrange them for winter, the season when the tea house is being shown, but Perriand’s original was unveiled in summer, so, for greater fidelity to the original, a summer arrangement has been used.

Charlotte Perriand – La Maison de thé, 1993, reproduction 2019 (image: © Adagp, Paris, 2019 Crédit photo : © Fondation Louis Vuitton / Marc Domage).

The dilemmas encountered by the Charlotte Perriand curators are exactly the kind facing the restorers of Notre-Dame: what are the rules of the game when exact reproduction is impossible due to gaps in our knowledge, lost technologies, or modern health, safety and accessibility regulations? Some would say that any attempt at recreation is foolhardy and that only a strict interpretation of the 1964 ‘Venice Charter for the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites’ – which calls for a visible distinction between old and new fabric – should be observed. But in France, where Eugène Viollet- le-Duc – author of a number of controversial restorations, including Notre-Dame itself – is still hugely influential, recreation, even if it results in historical inauthenticity, is the preferred option. “To restore an edifice means neither to maintain it, nor to repair it, nor to rebuild; it means to re- establish it in a finished state, which may in fact never have existed in any given time. Both the word and the meaning are modern,” Viollet-le- Duc wrote in his 1854 Dictionnaire raisonné de l’architecture française. While the end result may contravene all the rules of the ‘Venice Charter’, the journey there can be rich in lessons, not only with respect to materials and techniques, but also in terms of increasing our knowledge about the design phase of a project. And we’re not talking about a building here, but an exhibition where the impact on non-specialist audiences must be taken into account. Not in the habit of peering at archival documents, they are generally much more immediately drawn in by full-size reconstructions, whether of furniture, interiors or even graphic works. Some of Perriand’s giant photomontages – accomplished exercises in propaganda that had all been lost – have been remade for the show. Among them is La grande misère de Paris, created for the 1936 Salon des Arts Ménagers, which Barsac has reproduced from the original glass plates at 80 per cent of the initial size to fit into the available space. In his shoes, Perriand would surely have done the same – after all, nobody in the 1920s and 30s had the slightest qualms about doctoring photographs to present buildings, interiors and movie stars in an idealised light. Indeed, one might legitimately argue that the curatorial choices at this exhibition are an act of homage to her genius for creating a compelling image of her ideals.

Words by Andrew Ayers

This article was originally published in Disegno #25. To buy the issue, or subscribe to the journal, please visit the online shop.

Charlotte Perriand: The Modern Life is on at the Design Museum until 5 September 2021.

Charlotte Perriand: Inventing a New World ran from 2 October 2019 at the Fondation Louis Vuitton ran from 2 October 2019 to 24 February 2020.

RELATED LINKS