The Design Line: 10 - 17 June

The Design Line is back after Milan mania, with a bombshell report on The Bartlett, a creepy crawly solution to polystyrene pollution from down under, Ikea’s baby name catalogue, and a mysterious case of an architect-less skyscraper in New York.

Dining out at Studies of a Table, shown at 3 Days of Design (image: &Tradition).

Fair dealings

This year saw Milan’s Salone del Mobile bounce back (and you can read some of our reflections from the week here), with the fair reporting an attendance of more than 262,000 visitors (down from its high of 386,236 visitors in 2019, but given the absence of Chinese and Russian visitors this is perhaps to be expected). Yet Salone is not the only design week to take place this June, with Copenhagen’s 3 Days of Design maintaining impressive growth since its inaugural 2013 edition. Given the pandemic’s impact upon the Stockholm Furniture & Light Fair, the event has come to provide an increasingly significant focal point for Scandinavian brands (and Danish brands in particular), with companies such as Gubi, Hay, Muuto and Hem all using the event as a platform for new product launches and installations. 3 Days may lack the scale of events such as Salone, but it is all the better for it, offering a more tightly curated display of showroom launches and installations that are displayed within an easily walkable area of the city. This year, attention particularly fell on Fritz Hansen, which celebrated its 150th anniversary with a temporary pavilion from Henning Larsen Architects erected in the courtyard of the soon to reopen Designmuseum Denmark. The pavilion was beautifully executed and, pleasingly, its design was based around ease of disassembly, with the dimensions of its constituent elements selected such that they can be used within the future reconstruction of the brand’s headquarter. On a smaller scale, albeit no less impressive, was Studies of a Table, a project from &Tradition and All the Way to Paris that provided five international studios with identical briefs to produce a dining table. Drawing on talent from across Scandinavia, Japan, India, South Africa and the USA, the results were delightfully eclectic, highlighting the degree to which subjective taste, technical knowledge and material availability shape any creative response to a brief. Design weeks, it would seem, are back with a bang.

Would you still love me if I was a worm that ate plastic? (image: University of Queensland).

Worming a way out

Plastic. We have approximately 8.3bn tons of it currently, and just over three quarters of it is waste. So, how on Earth do we get rid of it all? Could worms be the way forward? A team of chemistry and molecular bioscience students in Australia have found a species of worm with plastic-degrading enzymes in their gut. The worms are able to break down polystyrene containers, which would normally take up to 500 years to decompose, using the polymers for energy and sustenance, with the research paper stating that, after digestion, “the polystyrene particles appeared partially degraded”. The researchers hope to use the worms, along with other natural enzymes that break down plastics, in future studies, as well as aiming to come up with a scalable recycling process. Will it be feasible to upscale worms as a way to deal with to plastic waste, or will it become another niche solution adopted by few? While the news is encouraging, it risks plastic-eating worms becoming another stopgap solution that enables the continued production and use of plastic. It may be some time yet before we see worms employed in recycling centres.

Reckoning at the Bartlett

Last week, University College London issued an apology to current and former students, almost a year after Bartlett School of Architecture alumni Eleni Kyriacou blew the whistle on conditions at the institution. Her dossier of student testimonies formed part of an in-depth report on the school’s environment, which was published last week by independent investigators Howlett Brown. The report makes for queasy reading, airing decades of a “toxic culture” where racism, sexism and cruelty from teaching staff became pervasive. The Bartlett had prided itself on its crit system, where students publicly defended their work, ostensibly to prepare them for the workplace. Instead, budding architects were subjected to humiliation, racial micro-aggressions and even physical abuse, with allegations of models being thrown out of windows, students being physically shoved by tutors, and a staff member throwing a laptop at a student’s face. While there has been public outrage, the official response has been decidedly milquetoast, with the RIBA suggesting it might look into a code of conduct for educators. For an industry that has spent years bemoaning its lack of diversity, it should be a stark wakeup call. For decades, women and people of colour have suffered abuse at the hands of the people who were supposed to teach them the skills they needed to become architects and designers. It’s a terrible loss, and an apology and vague promises to change should only be the start of a systematic overhaul.

The next generation of Norwegians could all be named after Ikea designs (image: Ikea).

Billy the kid

Selecting a name for one’s offspring is tricky. Should you name them after your beloved great aunt Agatha? While old fashioned names are deeply trendy right now, will your child be teased in the playground for being called Hortensia or Winnifred? Why is no one calling their kid Gary any more? So perhaps it makes sense to outsource the project to an organisation that famously has a lot of experience naming its progeny: Ikea. The Swedish furniture company has stepped in after its neighbours in Norway experienced a pandemic baby boom, with birth rates up 5 per cent. The company has selected 800 Ikea names from their back catalogues and made them available in an online name directory where they are displayed along with their namesakes and some whimsical meanings. Of course there is Billy, after the 1966 bookcase, which Ikea says means “youthful, funny and mobile". Some are perhaps a little prescriptive or strange for a baby (Ulrika means “exquisite and beautiful with beautiful legs”), which suggests there may be limits to naming humans after things. But then, try telling that to celebrities such as Gweneth Paltrow, who named her child Apple, or Jamie Oliver, who went all out with Petal Blossom Rainbow. If you’ve got a favourite piece of furniture, why not honour it by naming your firstborn after it?

David Crow: “thoughtful, considerate and always very cool” (image: David Levine).

In memory of David Crow

On 10 June, the graphic designer and educator David Crow died following a short illness, with the subsequent outpouring of tributes and memorials showing the impact that Crow made throughout his career. “A superstar in graphic design education,” offered Rebecca Wright, dean of academic programmes at Central Saint Martins, while Frances Corner, warden of Goldsmiths, remembered a colleague who was “thoughtful, considerate and always very cool”. Deeply interested in the connections between music and graphic design, Crow had trained at Manchester Metropolitan University at the time of the Hacienda, and his later work became synonymous with the city. After educational roles at University College Salford and Liverpool John Moores University, he rejoined Manchester Metropolitan in 2004, swiftly rising to become the pro-vice-chancellor and Dean of its constituent Manchester School of Art. Here, Crow played a key role in the school’s development, commissioning its Benzie building from Feilden Clegg Bradley Studios, as well as emphasising the need for education to engage with increasingly cross-disciplinary and collaborative forms of design. In 2016, Crow left the school to join UAL, where he restructured Camberwell, Chelsea and Wimbledon Colleges of Arts, prioritising collaboration across departments and the importance of digital teaching methods. Crow will be much missed, but his legacy will live on: the fourth edition of his highly influential book Visible Signs: an introduction to Semiotics is due to be published this summer.

Co-Living in the Countryside aims to cull the cul-de-sac (image: Davidson Prize).

Co-escape to the county

Now in its second year, the Davidson Prize is an annual multidisciplinary call for projects that offer “thought-provoking ideas around the design of the home”, with this year’s iteration focusing on investigation as to whether co-living could offer “a transformative key to the design of our homes” (NB: any proposals that said “no” probably didn’t get very far in the judging process). Step forward the winning team of Charles Holland Architects, Quality of Life Foundation, Sound Advice and Verity-Jane Keefe, who spun the theme into a proposal focused on rural co-living (a neat reorientation of the topic away from the much discussed urban co-living and towards regeneration of rural brownfield sites instead). Titled Co-Living in the Countryside, the team’s proposal took aim at the UK countryside’s “shortage of affordable housing” and reliance upon “a narrow development model” that results in “single-family units in car-dependent cul-de-sacs”. Instead, Holland and co. proposed a flexible timber-framed construction that would allow for shared facilities and owner-adaptation of private areas, overseen by a community-based governance model that would allow “individuals to co-exist while sharing resources, skills and spaces”. It’s an intriguing idea and one that seems deserving of the Davidson’s £10,000 cash prize – let’s just hope the idea can be taken further and pushed into reality. So long to cul-de-sacs; viva countryside co-living!

Super shady supertall

New York City has become the epicentre of a well-documented outbreak of supertall skyscrapers, as developers rush to reach for the skies – and profits. With land at a premium, building as high as possible obviously maximises the floorspace that can be sold off or rented out. But with supertall buildings comes super-great responsibility, which is why it was unnerving to learn this week that the architect of record for a 196m-tall hotel currently under construction in Hudson Yards has never heard of the tower he supposedly designed and signed off. A New York Times investigation has revealed that the professional seal and signature of 80-year-old retired architect Warren L. Schiffman had appeared on multiple projects for the developer Marx Development Group. Schiffman worked for the developers before he retired, and had signed a contract saying he would let them use his signature in return for quarterly payments. But the retired architect claims he hasn’t practiced for five years and never reviewed these particular building documents. He told the Times he was “baffled” that his seal could have been used as it hasn’t left his house, but then it wouldn’t be hard to whip up a digital forgery. David Marx of Marx Development has refused to comment. The city’s Department of Building said it hadn’t found any structural defects at the supertall hotel, thankfully, but it’s still a very tall mystery to get to the bottom of.

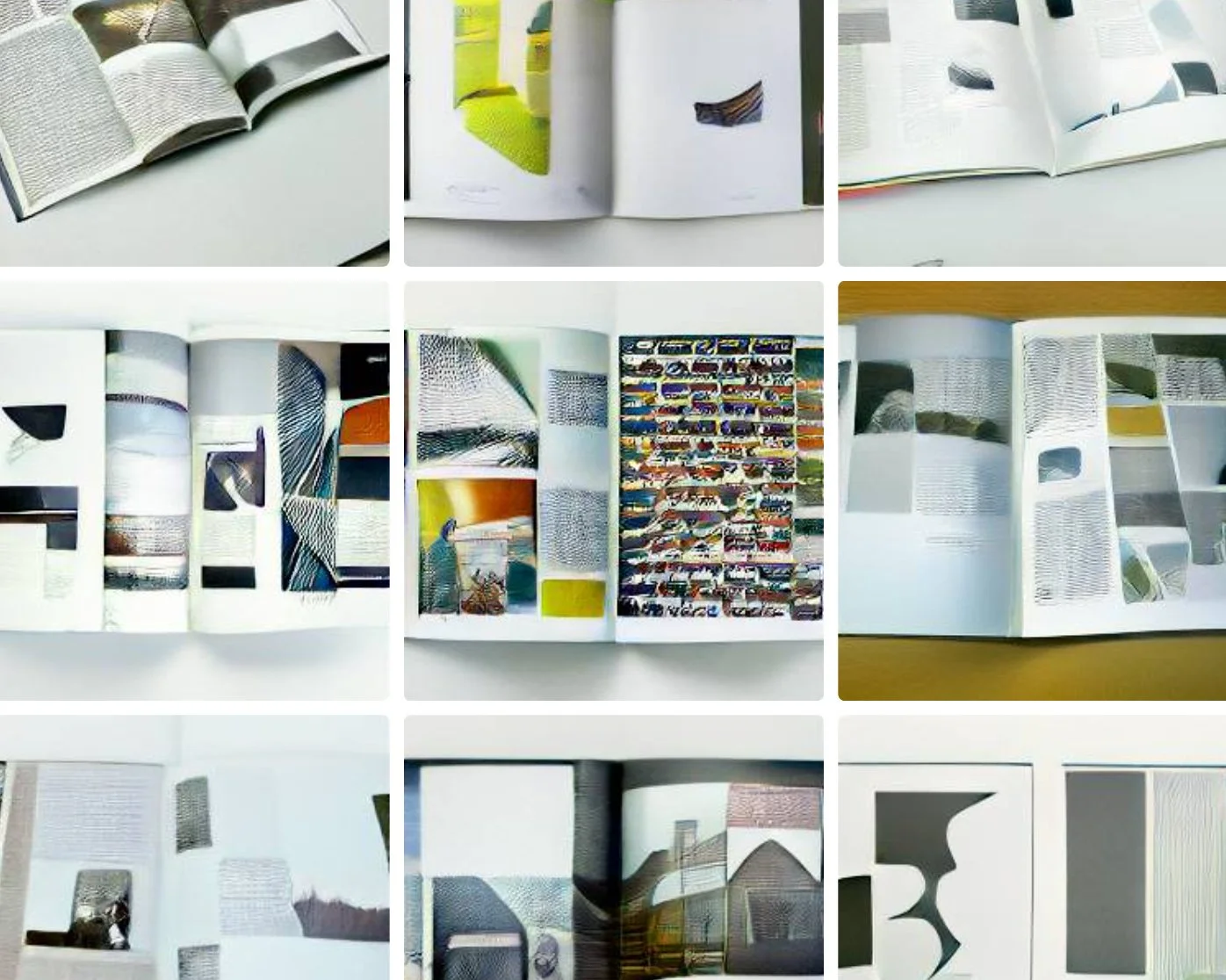

An AI vision of a quarterly design magazine (image: Disegno via Dall-E Mini).

Computer says wow

By now, you’ve probably heard about or seen some of the weird and wonderful images generated by Dall-E mini on social media, the publicly available child of the stronger, more accurate Dall-E engine. The text-to-image generator, which launched last year lets users loose with a neural network that uses the internet as its data set. Dall-E mini's ability to conjure up images of the most random and bizarre sentence you can feed it has gone down a storm with social media, appealing to the meme-obsessed nature of contemporary online society. Dezeen reported on the architecture critic Oliver Wainwright, who used the generator to come up with designs for next years’ Serpentine pavilion. The results are a clear blend of features from four previous pavilions giving a bit of an insight into the mind of Dall-E – and maybe those of contemporary architects. The generated images are almost realistic enough that they have a bit of an eerie and uncanny valley feel to them. But as it becomes harder and harder to distinguish renders from photographs, it makes Disegno wonder how real AI generated images will look in years to come. These images aren’t created in a vacuum, either, as the AI was trained on thousands of images found online, many of which belonged to artists and illustrators, many of whom are worried about copyright infringement from AI. At the moment copyright law on AI images remains vague but the generated images are public domain, or the users’ if they so claim, as the engine cannot legally be the ‘author’. In the spirit of science, Disegno asked Dall-E to generate images of “ a quarterly design magazine” (see above). Let’s just say we won’t be replacing our creative team with an AI any time soon.