Plants ≠ Objects

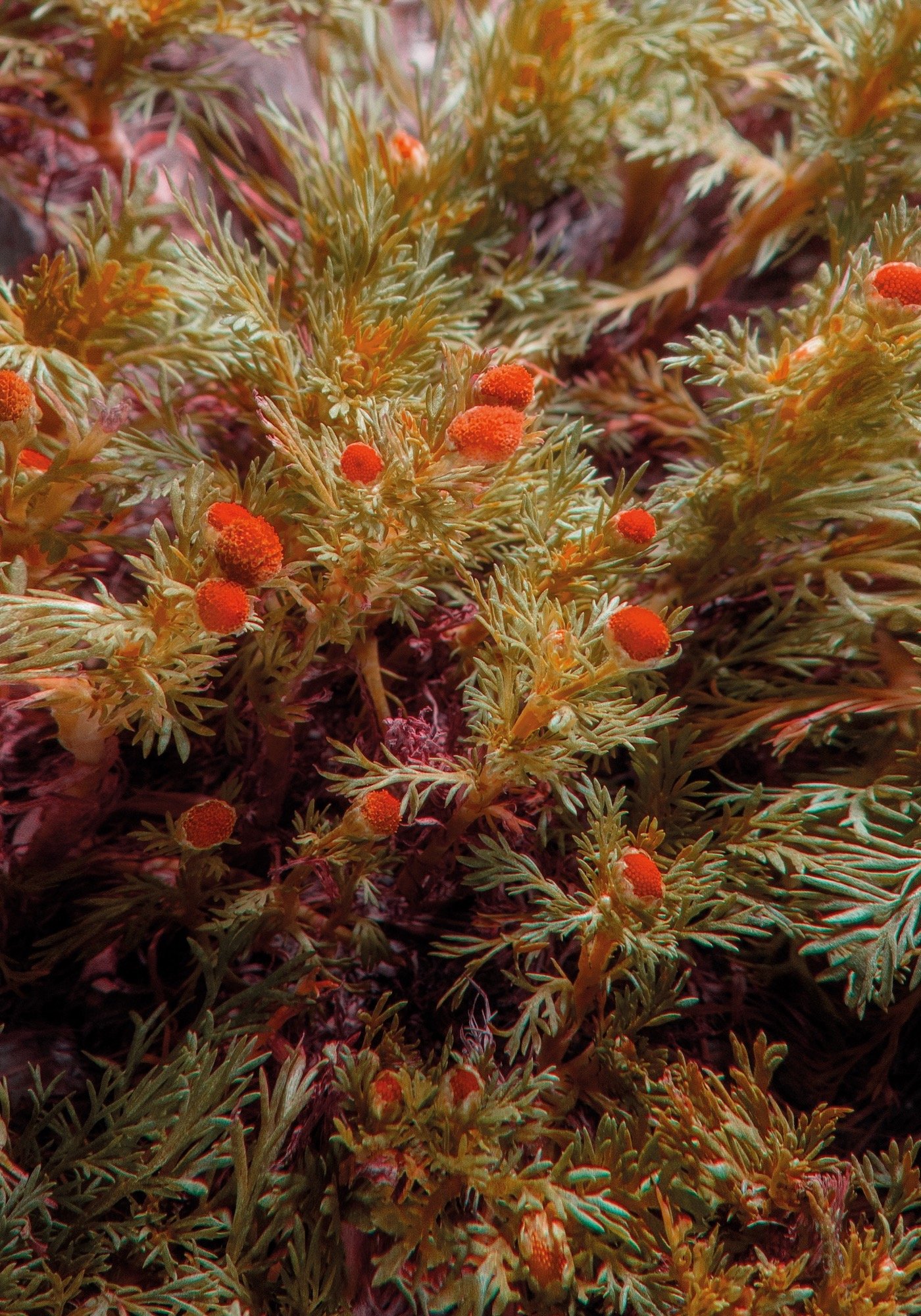

The images accompanying this roundtable were created by Overmind and commissioned by Studio d-o-t-s for Plant Fever. Towards a Phyto-centred Design (Stichting Kunstboek & CID au Grand-Hornu, Belgium, 2020).

Could challenging the way that design treats plants help to shift our perceptions of materials, value, resources and equity?

Plant Fever was born out of a conversation. In our research and curatorial work, we try to cast light on hidden or neglected facts and actors, telling their stories and putting them in conversation with a wider and diverse audience. Back in 2017, Laura had just finished reading a few mind-opening books – such as Éloge de la plante by the French botanist Francis Hallé and Braiding Sweetgrass by the American professor Robin Wall Kimmerer – when we had the opportunity to interview Dossofiorito, the design studio of Livia Rossi and Gianluca Giabardo. We spoke about their practice and how it looks at other-than-humans from a design perspective, and that conversation sparked a question: are there other designers who are looking into plants as their source of inspiration, subject of study, or allies in conceiving new scenarios?

Thus began the research that went on to become Plant Fever, a book and exhibition produced and presented by the Belgian museum CID au Grand- Hornu in 2020, and which is currently on display in the Museum für Gestaltung Zürich. There are two aspects that we wanted to target with the project. The first is to challenge the idea that plants only constitute the background of our lives and exist for us to exploit – something that is embedded in our Western perspective on the duality between humans and what we call “nature”. We want to explore how, through design, we might be able to mend that separation and reconnect the two. The second point is to look at “plant blindness”, a term coined in the late 90s by the American botanists J.H. Wandersee and E.E. Schussler to describe a cognitive bias against plants and our failure to account for their importance as living beings. Through art and design, can we break down this idea of plants as invisible?

Early on in our investigation, we realised that looking at design from a vegetal point of view could highlight how Western culture has often established a relation of domination over plants and considered them as mere commodities. From a design perspective, or even from a social perspective, when we objectify something, we are in a position of power to change its destiny or form. An object is passive matter. In that sense, when we consider plants as objects or as a simple resource, we fail to understand their full nature and complexity. While conducting research, however, we encountered a number of designers who were questioning that relationship with plants, proposing different ways of relating to them.

We imagined Plant Fever as a space of reflection, and an opportunity to ask questions. A lot of design work with plants is political, presenting designers as agents for change: the micro-shifts that they can bring about are highly relevant when dealing with natural resources, plants and other beings. Also, as Dossofiorito pointed out to us during that initial 2017 interview, when we interact with plants, we have to learn their language. We need to absorb their grammar and lexicon in order to be able to connect with them. These two aspects – designers as political agents who give value to what they touch and designers as agents who build bridges with other species – are essential. Through Plant Fever, we have learned about a new generation of designers working on a small scale with communities – either human, plant or animal – and also interacting with biologists and philosophers to establish deeper interdisciplinary connections. These ideas are essential if we are to build new futures based on mutual reliance.

At the end of both the exhibition and book is ‘The Manifesto of Phyto-centred Design’, a seven- point call for practitioners and the general public to establish a new sense of respect, responsibility and empathy for plants. The first point in the manifesto is critical: “Plants ≠ Objects”. To discuss this issue further, we convened a roundtable that would bring together designers from across disciplines and theorists from different fields to reflect on ways in which design might help to forge alternative relationships with plants.

The panel is:

Laura Drouet and Olivier Lacrouts are Studio d-o-t-s, a nomadic research-led studio active in editorial and curatorial production. The studio’s investigations focus on alternative social dynamics and experimental design perspectives.

Fernando Laposse is a designer whose work centres on plant fibres and their social, political, economic and environmental entanglements: his Totomoxtle project[1] creates marquetry from the husks of native corn grown in Tonahuixtla, Mexico, as a way of empowering an indigenous community to regain control of these grains, and make a livelihood and profit from a new material.

Natasha Myers is an associate professor in the Department of Anthropology at Canada’s York University and also director of the Plant Studies Collaboratory. She works with the concept of the planthropocene, which proposes ways of conspiring with plants and forming new reverential relationships with them, in contrast to the human-centric view of the anthropocene.

Livia Rossi and Gianluca Giabardo are the founders of Dossofiorito, a design practice active between 2012 and 2018 in Verona, Italy. Some of their work has focused on the human relationship with nature and, specifically, plants. Their Phytophiler project is a series of ceramic plant pots equipped with functional appendices, such as mirrors, magnifying glasses and climbing frameworks, which are designed to enhance human’s interest in and relationship with houseplants.

Emanuele Coccia is a philosopher and associate professor at Paris’s École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (EHESS). He is the author of The Life of Plants: A Metaphysics of Mixture (2018), which argues for plants as occupying a position from which we should analyse all elements of life, and addresses philosophy’s historical lack of interest in plant life.

Ioana Man is an architect whose work focuses on the microbiology of the built environment, examining the ways in which all architecture is inhabited not just by humans but by other lifeforms too. She is also the design lead of Faber Futures, a design agency founded by Natsai Audrey Chieza that works at the intersection of design, society and technology, and focuses on biologically derived materials.

What does it mean to treat a plant as an object?

Natasha Myers Plants have been relegated to the background of our lives: as a resource, there for the taking; as the substrate for our economies; and as the material fodder out of which we make our worlds. But that way of addressing the world follows a deeply colonial form. One of the frameworks that I want to bring to this conversation is an understanding that to render beings as objects is a colonial project – a project grounded in dispossession and extraction. We have to remember that colonial power is bound up in managing land and specifically managing plants – colonial powers continue to rework land and extract value through plants. Plants are at the core of the engines of our economy today, and they fuel capitalism and adjacent economies. So, we have to consider these values that have been set in place through an extractive, violent regime that has rendered plants as objects, and also enslaved people in the process. We have to preface the question you are asking with the realisation that rendering plant as object and resource is also bound up with the dehumanisation of people, with slavery, and a wide range of forms of enslavement. We have to realise that the split between nature and culture we seem to remain so caught up in is continually shored up through colonial power. So the beginning of the conversation, for me, is about de-tuning the colonial common sense that would have us talk about plants as natural resources. How can we start to engage with them as beings and what work would that require on our part? What work is required for us to be able to register the being-ness of these creatures with whom we cohabit the earth, and with whom we co-create our worlds?

“Design can help us reframe how we see the natural world, how we see plants, and how we see other organisms.”

Ioana Man Design can help us reframe how we see the natural world, how we see plants, and how we see other organisms. We tend to see them in isolation. When working on projects on the microbiome of the built environment, I’m often asked, “What are the good microbes that we want in a building?” And there’s no such thing as a “good” microbe, right? I wonder, when we think about a microbe, or a tree, or sugarcane, or any of these other organisms, how could we start to describe them not through what they do for us, but through what relationships they support – both ecologically and to do with human practices they impact?

Emanuele Coccia What interests me about plants is the fact that they have a way of being where forms are produced in a much richer way than in the animal realm. Plants are, in a way, designers. If you think about trees, they’re very strange entities because they’re living beings that add parts to their body every year. In the case of most animals, we reach a form and then just grow within it. So trees are, in a way, always questioning the problem of form. They have to decide which form to assume, every single year. They’re designers, perhaps in an even stronger sense than humans. Plants are also the living beings that radically changed the atmosphere of our planet. They made this planet liveable and breathable, and are also responsible for the fact that sunlight, which is the main source of energy for all animals, is available for us in a practical form. That’s why it is important to study plants.

Fernando Laposse There’s obviously this connotation of extractivism, which was turbocharged during the colonial time – an ambition to control and take everything as something to be possessed. Having worked for so long with an indigenous Mexican community, I’ve been looking at their relationship to maize, which is their totemic plant. But that’s almost a humanmade plant. You don’t have “wild” corn – it has been cultivated for thousands of years to reach its present form. So, I think that this question of dominating a plant or controlling and owning is not necessarily a colonial feeling. I think it’s a very big part of human nature. It’s about trying to utilise our intelligence and skills and observations to try and persuade plants towards helping us achieve what we want to. If we’re discussing what designers should be doing with plants nowadays, I don’t necessarily see it as wrong to consider them as materials, or to consider them as a commodity to be used, because that’s part of human nature. Humans have done that since the inception of agriculture.

Livia Rossi I think that it is important, however, to try to develop a different approach to nature: in “progress- oriented” societies such as ours, nature has traditionally been looked at as a set of exploitable resources. But in other cultures, especially in indigenous societies, nature has been perceived as a generous entity that offers us its gifts. This is not a subtle difference, because the notion of a gift implies reciprocity. In his work on this subject, the anthropologist Marcel Mauss claimed that gift-exchanging is strongly connected to the human capacity for establishing relationships and, therefore, creating social contexts. So, for me, the establishment of alternative, reciprocal attitudes towards nature is key to the development of a different perception of it and the role of humans within it. I also believe that a more widespread understanding of plants is important in this process of establishing a different relationship with the vegetal world. For example, we often don’t consider plants as being properly alive because they appear motionless to us. But of course they do move, they do change, and they grow in different ways depending on the situation they are in. We really need to let go of our speed and adopt a different timeframe to witness and participate in all of that. Through the Phytophiler and our other projects dedicated to plants, we were really trying to underline how “having” a houseplant is much more than showcasing a nice decorative element in a space. It is a form of co-habitation that presents a great opportunity for approaching, understanding and caring for otherness, in a context like the home where we are more at ease, and therefore more open and welcoming towards this experience.

“If we’re discussing what designers should be doing with plants, I don’t see it as wrong to consider them as materials. That’s part of human nature.”

Fernando I think the issue is perhaps this super-colonialist view of, “Let’s just completely plunder plants.” Perhaps something to relearn or look at is to focus on our traditional communities worldwide, because these are people who still have a radically different philosophy of how to approach our relationship with plants by understanding the interconnections between us and them in a more fruitful way for both organisms. Something that I learned from working with an indigenous community for the past few years is the idea of inter-species design – where you as a designer are perhaps not just designing for the benefit of the designer, but saying, “Okay, how can we collaborate with plants to create improvements for the both of us?” That sometimes has to be done through the production of a material, because, ultimately, we have built our world on matter. I think it is a little bit utopian or naïve to just assume that we can forget about that altogether. It’s more a question of, “Can we reframe it? Can we go back a few steps behind? And can we listen to the people who are still living in tune with that, to be able to move forward?” It’s about diversifying solutions, because so far, we are re-approaching the issues with a very Western mind. So, in my case, I’ve tried to not exclusively think about technology and new materials, but also about reviving or revitalising old systems that worked. And this is often through looking at traditional communities.

Emanuele I think we have to avoid this attitude that Western culture is necessarily an objectifying culture. It’s a very neocolonialist attitude and it’s not something that I agree with. When we ask what it means to treat something as an object, it reminds me of the work of the anthropologist Alfred Gell, who showed that a huge part of our culture deals with objects in a very specific way – art. What we call art in Western society is a sort of animism, because within it we are relating to objects as if they were subjects. Even with objects, we can have different attitudes. When we say that something is an artwork, we recognise that this object exists in the same way as a subject exists. That’s the key, I think. It’s not a question of becoming different, or transforming the world, it’s about recognising that in the realm of objects, or even design, there is a special attitude whereby you create an object, but the object exists with subjective attributes or qualities. That’s why, in my opinion, design and art play a huge role in an ecological crisis – they’re realms that are training people to have a different relationship to objects and to help them see that matter is not just matter, or not just a function. In a way, design is really the impossibility of letting matter exist just as matter, because the designer is obliged to give form a meaning. So every piece of matter that is designed contains something that belongs not to matter, but to the mind. That’s why designers are so important.

Natasha It’s about relations [between things] – you can produce materials, but those materials are precious and charged with a different relationship. They’re experienced as a gift, not as an extraction. Yes, we can harvest and draw in these incredible gifts, as Livia is talking about, but if we’re relating to them as gifts, then we have to reciprocate. One of the things that I would want to achieve is a reconfiguration of our understanding of the human – to understand that we are of plants and that we have been shaped by them. To begin with, they entrained our sensorium: they taught us how to taste, how to smell. They taught us about beauty, they taught us about aesthetic forms, inciting intoxication and exciting our pleasures. If we start to recognise that we are of the plants, then the next step is asking how can we return that support? So, one concept I’m working with is the indivisibility of plants and people, and beginning to recognise that our future hinges on their future. What can we do to support their thriving, so that they can help everybody live? This is the planthropocene – this recognition of indivisibility and this realisation that we need to be in a reverential relationship with plants. I’m also working with this concept of conspiracy, which means to get on the same side, but also means to breathe with. If plants breathed us into being, how can we get on their side and support their thriving? Part of this process is really thinking about the human-plant relation[ship] – not dreaming of a world without humans so that plants can survive, but dreaming about a world of conspiracy, or co-constitution, or collaboration. That reconstitutes our relation to something that is less extractive. It’s less about designing for us, but about designing with and for other beings and designing for the relations that plants have set up in the world – precisely those that our practices tend to sever. I think design is a powerful place of reworking those relation[ship]s.

“In a way, design is really the impossibility of letting matter exist just as matter, because the designer is obliged to give form a meaning.”

Ioana A lot of my thinking around these issues is to push back on the modernist exceptionalism of the designer as the figure who shapes how we live. And also the modernist obsession with control through cleanliness, exclusion and efficiency. So a lot of my work is to establish frameworks, tools and processes that allow for different kinds of outcomes. Some of what we do at Faber Futures is to think about what a design brief is actually for. Do we work on briefs for products or for a production system that can equitably support people and the planet? Is the architect’s brief to design buildings for profit? Or is the brief to design space for human-plant-microbiological interactions through gardening or foraging? What was striking about what both Natasha and Fernando were saying is this idea that we should maybe be writing briefs for processes and relationships. Looking at Fernando’s work, that’s kind of happening already. It feels like you’re writing the brief not for the artefact, but for the making with nature. It all goes back to, “What do we want to achieve in design?” Maybe we need to strive for things that are not profit or domination.

Emanuele It’s funny – when we walk down a street where there are 50 or 60 trees, nobody’s thinking, “This is actually quite a crowded place.” But if there were, I don’t know, 50 or 60 dogs, we would feel very differently. So there is a problem in acknowledging that plants are living: we consider them as a part of the visual landscape, and not as living beings. If we could start considering them as real subjects, that might change a lot. Once we start to acknowledge that plants and trees are alive, and that they have the same status as animals, everything changes. All this debate about vegetarianism and veganism, for instance, would change radically because you couldn’t say that you wanted to avoid eating living beings, but you also couldn’t stop eating them because you have to eat something. To be an animal means to acknowledge that the life you’re living comes from other living beings. You are, in a very literal sense, a reincarnation of other living beings.

Fernando It’s easy to explain my ideas to the people that I work with, the farmers, because they’re already a lot more empathetic and a lot more understanding. The bigger challenge is always, how do you explain them to more of an urban crowd? So, without getting super cheesy, I try to give a bit of human personality to the plant when I’m describing it. When we harvest agave, we wait until almost the end of the plant’s life. So when I’m talking about the agave, I talk about the end of their lives, when they do something incredibly poetic – they basically put all of their energy and all of their sweetness into creating a 10m-long flower that is pollinated at night by bats. And so, right before they die, as one last act, they put all of their energy into copying themselves and making babies. When you frame life in that way, people start to think of themselves and their children. But the corn is a big challenge at the moment because I get looked up a lot by interior designers, who are interested in my work because of its ecological aspect. But as soon as we start to talk about the colours of the corn, they ask me about Pantones. “Give me all the RAL or Pantone codes of your material.” Which is impossible – it’s as if they were asking for the Pantones of people. I mean, it’s almost as wrong as that. I think that standardisation has become so prevalent, that sometimes you need to reflect on how ridiculous it is to expect that in a plant, because it would be equally ridiculous to expect that in a person.

Emanuele I have no problem with anthropomorphism in the sense that, firstly, it’s unavoidable, and secondly it’s necessary. When we say, as botany now does, that plants think, we are not just anthropomorphising plants, we are also vegetalising human beings – we are saying that thinking is something that is common to human beings and plants, and which is neither purely human nor purely vegetable. From this point of view, anthropomorphism is also a practice of dehumanising human beings and that’s interesting as a negation of human exceptionalism. From a biological point of view, one of the major consequences of the theory of evolution is the fact that every species is a patchwork of features from different species. Our own bodies give us access to a multi-species experience: in a sense, we are not purely human, but are already biodiverse. Everything we have exists in every other species under another form.

“Paradoxically, another way to talk about plants’ importance is to speak about us – humans – and how much our life depends on them. ”

Olivier Lacrouts We’ve been working on an organic farm here in the French Alps for the past month and a half, talking with the people who own the farm about the plants that live here. Those kinds of questions, “Are plants objects?” or “Is it difficult to explain that plants are alive?” do not really seem to apply here – they are probably only relevant for an urban population that is distanced from other-than-human beings. It’s that distance from where the materials we use come from that causes the problem. People who live closer to so-called nature have the vocabulary to express what these beings are. In Plant Fever, for instance, there’re two projects by the Latvian designer Sarmite Polakova called Pineskins and A Story About a Pine Tree, which examine the production of pine timber, comparing it to cattle breeding practices and showing us how we tend not to consider forests as living entities but as mere “factories to deliver wood”. In her research, Sarmite explores the potential of new relationships with pine trees. In common forestry operations, only the trunk of the tree is seen as useful material, for example, whereas the bark is extracted on-site in the forest and then just left there. In a series of drawings, Sarmite shows how the bark is almost like the skin of an animal – it’s a way of confronting the audience with the fact that the plant is a living being.

Laura Drouet We also featured a project by the Austrian designer Alexandra Fruhstorfer called Menu from the New Wild, which proposes eating certain plants and animals that have become invasive in Austria as an alternative to using poisonous substances – such as glyphosate or zinc phosphide – to get rid of them. Many [visitors] expressed their reluctance and disgust at the idea of eating a raccoon or a turtle, claiming that it would be unethical; they were, however, not disturbed by the prospect of eating two plants, Japanese Knotweed and Himalayan Balsam. As a vegetarian I do understand their point, but it does say a lot about the distinction we create between animals and plants.

Emanuele But I don’t think our attention towards plants should be reduced to a moral level, because it’s more about an explosion in our knowledge of plants. The city, at least in its origin, was an association between human beings and vegetable beings – we built cities because we built gardens, and we took food from our gardens to support ourselves. Today, cities conceive of themselves more and more as monocultural entities, which is a huge problem, but not because of any lack of attention towards plants. The problem was the demographic explosion of the 1950s, when we quickly built cities because we had to host billions of people coming into them from the countryside and we just didn’t have time. The problem was haste. I think the reason that design is now looking at plants differently is because we know so much more about them. Botany has experienced a revolution in the last 40 or 50 years with the discovery of the importance of symbiosis to evolution, which means that cooperation is more important than predation or competition – this was the work of a biologist called Lynn Margulis. That means that plants may actually be more important for our understanding of life on this planet than animals, because their life is not based on predation – botany has become so important for understanding life on a planetary scale. We should stop reducing everything to a moral movement and to a movement of more respect, because much of it is also about the fact that we have discovered something amazing.

Laura Cultivating fascination towards plants by raising awareness of their poetic singularity and “powers”, such as Fernando pointed out with the example of agave, is one way for us all to understand that plants are more than objects or materials and that they have a design of their own – for instance, to multiply and spread. Paradoxically, another way to talk about the importance of plants is to speak about us – humans – and how much our life and that of many other beings depends on them. Being aware of this interdependence makes you change your mind on the vegetable realm.

“Design has been the backbone of capitalism. In that sense, it is in a compromised position. We have an original sin.”

Natasha Animals can, of course, look back at us and we can produce all kinds of affinities with such creatures. It’s harder to do that with plants. But all beings rely on plants and we are held together as a planet by the plants. If you want to help bring back endangered animal species, you have to remember that it needs a whole world and that world is going to be made by plants in some way. You cannot save a creature if you’ve destroyed its land and its relations with plants. The point that I’m trying to bring forward is that we all need plants. Environmental, climate and racial justice all hinge on healing people’s relationships with land and plants. Growing good relations with plants is a way of fostering plants’ relation[ship]s with all other beings. So instead of thinking, “Oh, we need some habitat to make sure that we’re saving the animals” – habitat is such a passive concept – what if we were to understand plants as the world-makers we need to heed? These are the creatures who terraformed these lands making them habitable for all the rest of us. This question becomes who is the “we” that matters? We need a “we” expansive enough to include all kinds of multispecies solidarities if we are going to be able to reckon with the enormity of the challenges that lie ahead. I think we have to reckon with what it is that plants are actually holding together for us.To turn our attentions from animals to plants is to recognise the centrality of plants’ role in our planetary way of life.

Gianluca Giabardo I’ve been thinking about the role of design in all of this, because design has traditionally been an innovation and technology-focused discipline. It has been the backbone of capitalism, consumption and industrialisation, and has enabled the extraction and exploitation of raw materials. In that sense, design is in a compromised position, which presents a big challenge for the discipline. So, how do we enable – or bring forward – a discussion where this idea of bridging and eliminating the separation between nature and culture is done through the work of design? As a discipline, we have an original sin that is hard to let go of. For this purpose, I really like the idea of conspiracy that Natasha brought up. I am exploring symbiotic conviviality in my doctoral research through the practice of natural fermented bread baking. In my understanding, which relies on the work of Lynn Margulis that Emanuele mentioned, symbiosis is a form of co-existing survival, while conviviality is both living with, and – as Ivan Illich proposed – individual freedom when it is realised in personal interdependence. I think that when we acknowledge this possibility to think together, be together, live together, and breathe together with “others”, we return to the idea of the garden. There are no “others”, there is only a plural “us”. I feel we should stop this polychotomy, which also exists in our languages, that divides humans from others – it only keeps reinforcing a perception of a separation that does not exist.

Natasha We need to figure out ways that we can conspire with plants if we are going to live on this planet well. So, precisely the kinds of deep work that can transform them from being objects to becoming beings who are worthy of our address. We should actually be learning design from them and so I’m interested in how the way we decide to relate to plants though design will decide the world that we live in, in the future.

Fernando A bit of a challenge as designers, is that we see plants as resources, but it’s very hard to get out of that now, because it demands a whole restructuring of our world. We’re in a hyper capitalist world, where you don’t have much counter-balance from an opposite ideology, so if you want to preserve something, you almost have to assign an economic value to it. The conundrum is that if you don’t assign an economic value to ecosystems, there’s no way of controlling them. Something I’m interested in at the moment is the fact that the traditional communities we’re dealing with don’t live in a vacuum: they’re still affected by economic chains and globalised markets. So one challenge that designers have, and also a huge opportunity, is to look at how you could create parallel sources of revenue that allow you to not compete with these established ways of seeing everything as a resource. What we’re doing right now with the corn, for example, is looking at what we do with waste, which in our case is the grain because it has become the least profitable part of the plant. A square meter of our material is equivalent to a tonne and a half of grain, so it’s about seeing whether we can use that grain to feed the farmers growing it, and then create a new sub-economy that is in competition with the wider ravenous overproduction of corn. Perhaps one way forward is some sort of capitalist activism. That could be dangerous, but there may be a way of hacking that wider system, which is, unfortunately, almost impossible to operate outside of nowadays.

Olivier Yes. Probably one of the main challenges for designers such as you, who work closely with communities, is to create these sub-economies and maintain them at a small enough size. Because once you scale up production, even if you’re using leftovers, you risk establishing a new monoculture. Staying small is thus part of your responsibility.

Fernando I completely agree, but staying small has also to do with the amount of added value that you can generate. In the case of what we’re doing, we can put such a markup on the material that we don’t feel the necessity to go and chop down half a mountain to plant corn. We’ve downscaled and the overall corn production of the village is a lot less than it used to be, but there is such a markup on this material that it’s allowing them to have a certain independence from this frenzy to overproduce. It’s about staying at a sustainable size, economically and environmentally.

Ioana You’re talking about a shared language that can communicate value and, under capitalism, that shared language is very often money. I wonder if there is an alternative way of regarding the living world and finding a different shared language. I navigate biotech on one side, and design and architecture on the other, which are both notoriously exclusive fields that talk in lingoes and abstract terms. The challenge with both is to find the stories and metaphors that open up what it is that we do to the real world. For instance, working with microbes in built environments is also my grandparents putting pots of milk on top of their cupboard, and the microbes in the room transforming those into yogurt. It’s this kind of knowledge that actually embodies the relationships that we have with plants, microorganisms, and the living world, and these real-life stories communicate different approaches to design and challenge the idea of who counts as the designer. You mentioned design’s original sin, Gianluca, but is that where design started? I know that’s one way of seeing the situation, but aren’t ancient fermentation vessels design? Aren’t permaculture strategies design? Maybe we’re just too limited in who counts as the designer and we should learn from all of these other designers who embody a lot of these values in their work.

Gianluca I totally agree with that, but there is this narrow view of design that is mainstream in many universities and which we’re educated in – or at least I was. When you were talking about the economies of the maize grain and husks, Fernando, it reminded me of this interview with the chef Dan Barber on [the BBC World Service show] The Food Chain. He was saying that he was known and acclaimed for his bread, the grain for which was sourced from a nearby farmer. So he felt that he was supporting local agriculture and economies. But when he went to visit the farm, he found out that the emmer wheat he was using was only a small fraction of the farm’s overall production: to get him the grains needed to bake his bread, the farmer had to rotate the field, and grow millet, barley and kidney beans as cover crops. So the chef realised that he needed to use all the produce that went into that rotation and then developed a menu around it. This made me think that it’s crucial to find ways to think systemically about the implications that certain kinds of economies have on the ecosystem.

Natasha The question that I want to offer is, “What is your garden growing?” What are we growing in our homes; what are we growing outside of our homes; what are we growing in the design projects that are being dreamed up and funded today? Because we could be growing the apocalypse, right? We can grow capitalism really easily, we know how to do that, and the question I’m interested in provoking designers with right now is, “Can we design for a different future?” That means reckoning critically with all of the terms that capitalism served us. It would be easy to grow “sustainability”, which in many ways is about sustaining capitalist growth, but then that’s not helping. We have to recognise the ruse of sustainability rhetoric and re-think what kinds of ecologies we can build, which are relation[ship]s that don’t necessarily have extractive economic forms. That’s something that I’d love to have as a core of this new thinking from within design.

Gianluca I think that different futures have always been at the root of design. We want to design a different future, but thinking about who thinks what that future will be, is important. We have to first design spaces and modes for deliberation: how is this future going to be imagined and discussed and decided together? Because otherwise, the role of the expert, of the designer, remains in the hands of the few, and will inevitably replicate problematic dynamics.

Introduction Laura Drouet and Olivier Lacrouts

Illustrations Overmind

This article was originally published in Disegno #31. To buy the issue, or subscribe to the journal, please visit the online shop.

1 See ‘Design for a Rural Mexico’ by Martha Pskowski and Carlos Álvarez Montero, published in Disegno #22.