A Rebirth

Stefan Diez’s Ayno lamp for Midgard, the company’s first new design in 70 years (image: Peter Fehrentz, courtesy of Midgard).

In developing its first new design brief in 70 years, the German lighting brand Midgard resolved to set out precise requirements. “There were no restrictions at all in terms of the design,” notes David Einsiedler, Midgard’s CEO, “but regarding sustainability and functionality, we were careful to create a clear roadmap. It needed to be an adjustable lamp that was made from as few materials as possible; the materials needed to be recycled or recyclable; and the LED needed to be changeable by the customer without any special tools. These were strict requirements.”

Precise constrains, then, but this kind of rigour befits a company that is widely credited with inventing adjustable lighting. Midgard was founded in 1919 by the German engineer Curt Fischer, who brought the exacting nature of his discipline to bear on the problem that he set himself. At the time, workshop and factory lighting was only provided by ceiling-mounted pendants, whose static design could not be adjusted to suit different tasks and which often caused unwanted shadows. Fischer recognised that the best way forward would be a more flexible, mechanically sophisticated form of lighting – one which could be quickly and easily adapted to suit any task. It proved the birth of the adjustable lamp. “The company archive contains many dozens of different solutions to this problem,” notes Einsiedler, “most of them patented by Midgard and/or Curt Fischer.”

“There were no restrictions at all in terms of the design, but regarding sustainability and functionality, we were careful to create a clear roadmap.”

Midgard gained international repute when its new adjustable lights were adopted by the Bauhaus in 1926 for its new buildings in Dessau, with its TYP 113 lamp in particular subsequently picked up and championed by the school’s masters, such as Walter Gropius, Hannes Meyer, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy and Lyonel Feiniger. “We later envied the inventors of the Midgard lamp’s arm,” noted the Bauhaus artist and designer Marianne Brandt. “Our lamps were adjustable too, but they simply weren’t as elegant.” Yet while Fischer continued to innovate throughout the 1930s and 40s – investing in materials such as enamelled bakelite and new production technologies including aluminium pressure casts – the company began to decline in the second half of the century, first under the state control of the DDR, before struggling against the cheap imported products made possible by globalisation.

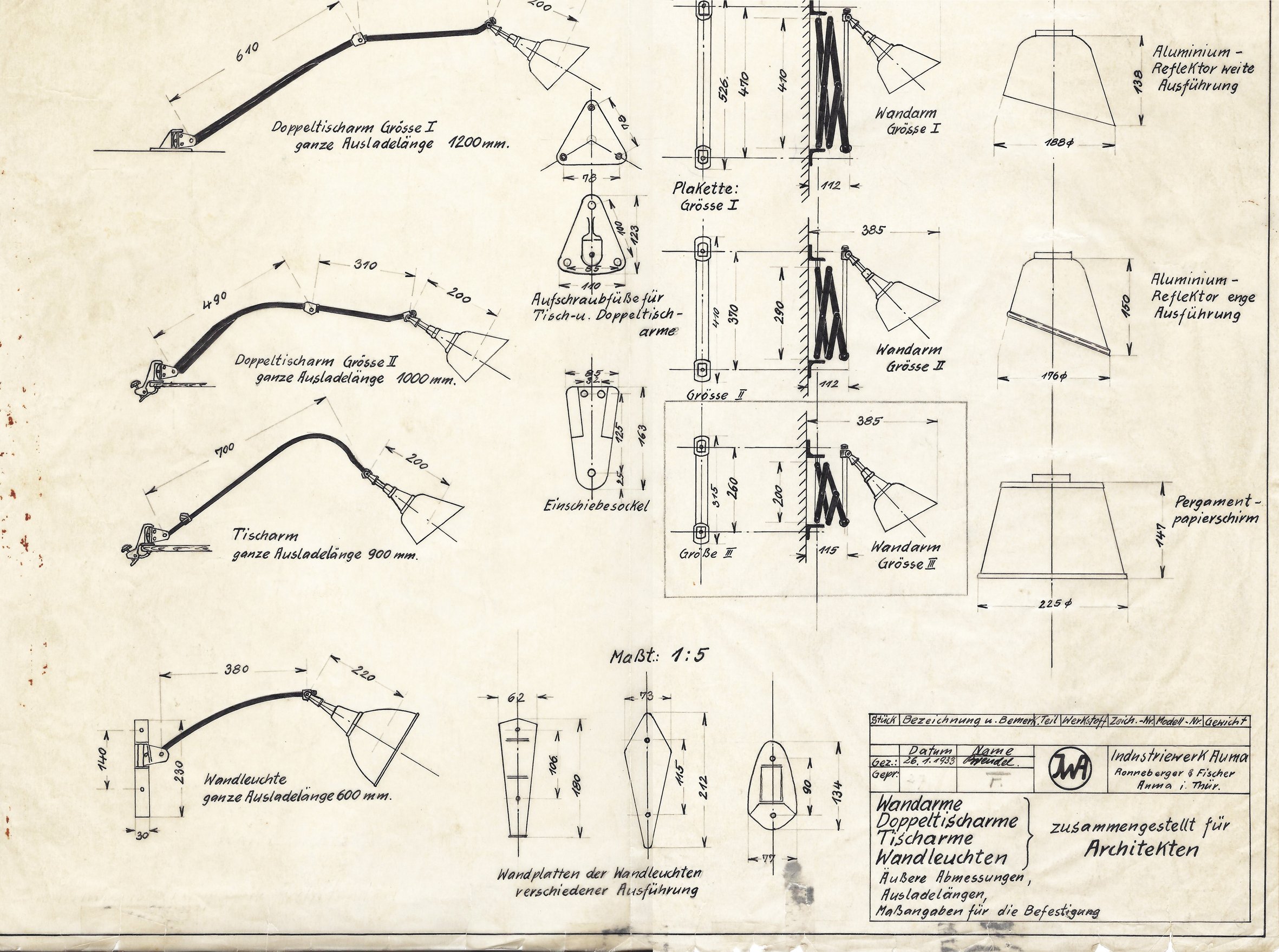

Technical drawings of different Midgard lamp models, originally developed for architects (image: Midgard Archive).

In 2011, Midgard filed for bankruptcy, prompting Einsiedler and his business partner Joke Rasch, who had previously founded the design and architecture practice Ply Atelier together, to step in. “I’d known Midgard since around 1999 when I bought some of their lamps because of their quality and the flexibility that they provided,” says Einsiedler. Rasch and Einsiedler initially tried to find investment for the brand in 2011 without success, but subsequently returned in 2014 with a proposal to license production of the company’s Modular lighting system for an architectural project. “We knew that all the tooling still existed and we loved the idea of building and offering different types of the Modular system as part of our work,” says Einsiedler. But following conversations with the Fischer family, negotiations moved in a different direction. “After months of discussions and meetings, we were offered the whole company, including its copyrights, archive, machines, tooling and brand,” says Einsiedler. “And we agreed!”

A TYP 113 lamp installed in the New Bauhaus (which is today known as the IIT Institute of Design at the Illinois Institute of Technology), an institution founded in Chicago by László Moholy-Nagy in 1937 (image: Midgard Archive).

Under Rasch and Einsiedler’s leadership, the company began restructuring production of its existing lines, as well as digging into the company’s extensive archive to restore designs such as the K831 adjustable pendant lamp. But while Midgard explored its past, Rasch and Einsiedler were simultaneously pivoting towards the present. The company had not produced a new design since the 1950s, but Rasch and Einsiedler were determined that Midgard would return to creating new lamps that felt sympathetic to the company’s heritage, while also marking out new territory. After a successful reedition of the TYP 113 in 2019 to mark Midgard's centenary, the road ahead became clear. “We had learned enough,” says Einsiedler, “to go ahead with our first new Midgard design.”

To execute this new design, Midgard began early work in 2017 when the company reached out to Munich-based designer Stefan Diez. Rasch and Einsiedler both admired Diez’s practice, seeing parallels between its rigour and the work of Fischer in establishing the company. “Stefan for us is a ‘materialist’, insofar as he knows about the characteristics of materials, how they behave together, and how they can be connected in a useful way,” explains Einsiedler. A short while after Diez had received their brief, Rasch and Einsiedler visited his studio to see his first response. “It took a matter of seconds before we knew we were on the right track,” says Einsiedler. “Our brief had been hit perfectly. We immediately felt that it belonged to the Midgard family.”

Adjustment in the Ayno is provided by means of the electrical cable holding the lamp’s fibreglass rod in tension (image: Peter Fehrentz, courtesy of Midgard).

The new addition to that family is the Ayno collection of adjustable lamps. Whereas Fischer’s lamps were based around precisely calibrated engineering, Diez’s interpretation of the typology is grounded in a simple idea: replacing mechanical complexity with material efficiency. The lamp’s head is positioned on a fibreglass rod, to which a slim electrical cable is affixed with two adjustable rings. As these rings are moved along the length of the fibreglass, they place the cable under tension, which in turn bows the rod into elegant arcs to suit any position, with further calibration available through the swivelling lampshade. It’s a system that allows for careful, precise adjustability, but without the need for a single joint – the movement is provided for by the material itself. “It is a unique mixture of Stefan’s talents and our requirements,” summarises Einsiedler.

Midgard’s original snake and sun logo. The company was founded by Curt Fischer in 1919 and has been under the control of Joke Rasch and David Einsiedler since 2015 (image: Midgard Archive).

The mechanism developed by Diez has now been patented, but material and mechanical innovation was only one part of what the team hoped to achieve with Ayno. “We wanted to follow Midgard’s history of engineering but with a clear focus on sustainability, which is the most important element for today,” explains Einsiedler. Thanks to Diez’s reduction of parts, the Ayno can be produced from three main materials, all of which are recyclable. The lamp’s base is made from steel, its rod from fibreglass, and the rings and lampshade from a recycled ABS/PC sourced from an automobile factory that recycles offcuts from its production line. While the team debated the merits of including a plastic in their design, and considered employing aluminium instead, they ultimately found that a holistic interpretation of sustainability found in favour of the ABS/PC. The energy costs required to recycle a metal such as aluminium would be prohibitive if the lamp was to be sustainable, while the use of plastic kept the weight of the lamp low, making it more efficient to ship.

“Ayno is a unique mixture of Stefan’s talents and our requirements.”

The materials selected for Ayno have a further role to play in matters of sustainability. While Ayno’s specialist ABS/PC elements, such as its adjustment rings, are produced centrally at Midgard’s home in Germany, the lamp’s more standard elements, including the fibreglass rod and steel base, can also be manufactured in other markets so as to further reduce the environmental costs of shipping. “It was always part of the briefing that Ayno needed to be designed in such a way that it could be produced everywhere to limit transportation,” explains Einsiedler. “We wanted to chose materials that were available locally to Midgard, but also look at assembling the lamp in regions in which it performs best so that we’re not unnecessarily shipping products all over the globe.”

To further aid sustainability, Ayno is designed to be flat-packed (and it ships without plastic air cushions, which have been foregone in favour of biodegradable packaging produced from cornstarch) and can be assembled in three minutes. This ease of assembly is intended to support customers during the lamp’s setup, but also ensures that the design can be quickly disassembled to allow for the replacement of individual parts if required, not least the LED itself. Whereas many contemporary LED lamps require specialist repair if the light source is to be replaced, the Ayno is fitted with a standard E27 bayonet socket ensuring that anybody can simply open its diffuser, remove the LED and fit a replacement. In this manner, Diez’s design fulfils the last of Einsiedler’s “strict requirements” developed in conceptualising the lamp.

Ayno is produced from three main materials – steel, fibreglass and recycled ABS/PC – all of which can be recycled (image: Peter Fehrentz, courtesy of Midgard).

It is through these requirements that Einsiedler and Rasch see ties to Midgard’s past. While Fischer’s original lamps utilised careful design and engineering to grapple with the needs and production methods of the 20th century, Diez’s lamp applies this same approach towards dealing with the dominant issue facing 21st-century design – sustainability. “Working with the company’s history and knowing where Midgard has come from is what has enabled us to build this bridge to the future,” says Einsiedler. It is an approach that proved vindicated when Ayno was selected as one of the 2021 winners of the prestigious German Sustainability Awards.

With this success, Ayno has marked out its own place in Midgard’s history, continuing the principles of Fischer’s original work with adjustable lighting while adapting them to the realities of contemporary design. “It’s an ongoing story,” notes Einsiedler, “and we´re very thankful to be a part of that story. We’re grateful to be in a position where we can develop such a historic manufacturer and help to transform it for the future.”

This article was made for Midgard.