The Ground of Palestine

Even as early as the 1900s, Zionism could be understood as a terraforming, climate-changing, time-warping and anthropomorphising movement. It sought to transform the land, architecture and archaeology of Palestine, make the desert bloom, and transcend and recast millennia of exile. Whereas the pilgrims to Palestine of the 18th and 19th centuries had encountered ruins that seemed to verify the Biblical prophecies of a deserted Zion, for the rising Jewish nationalist movement, the processes of construction and terraforming were validating acts of return.

Meanwhile, Palestinians were being marginalised by the colonial powers that controlled the region – first the Ottomans and then the British. These empires developed and deployed technologies of survey, vision, engineering and archaeology across the region, which meant that, slowly, Palestinians were written, archived, visualised and mapped out of Palestine. In this respect, those colonial empires have left behind a living legacy: a juridical, scientific and technological violence that has been weaponised by the Israeli settler colonial regime. While this violence is clearly felt by the Palestinian populace, its gradual implementation has meant that it has been naturalised within swathes of Israeli society, as well as in many parts of the international community. As part of this, archaeological research has been co-opted as a mechanism of settlement and colonisation, with excavation of sites used to support particular national narratives, elide others, reshape territories, and allow for the introduction of extensive surveillance and security apparatus.

This attempted overwriting of Palestine, escalated since the Nakba of 1948, has been resisted on the ground as well as through scholarly research and the development of counter practices. The late Edward Said was one of the first to clearly outline the ways in which Western empires imprinted their imaginary perceptions of the East onto Palestine. The researcher Salman Abu Sitta’s reconstructive cartographies of pre-Nakba Palestine have, for several decades, painstakingly retraced the dense network of habitation that existed in British-mandated Palestine. Meanwhile, anthropologist Nadia Abu El-Haj, in her groundbreaking work Facts on the Ground: Archaeological Practice and Territorial Self-Fashioning in Israeli Society, has continued this research into the construction of social imaginaries and political structures though Israel’s use of archaeology and architecture. An attempt to grasp and reconnect with a landscape or memory that is out of reach or under threat of erasure drives many Palestinian artworks, such as Yazan Kahlili’s Landscape of Darkness (2010), a video and photographic work that is shot at night, documenting the West Bank’s Israeli-controlled Area C.

To explore these issues, I met with the Palestinian architect and artist Dima Srouji and archaeologist Silvia Truini (both of the group Depth Unknown) to speak about their work around architecture and archaeology, the manner in which these disciplines are inherently political, and the ways in which they have been operationalised and come to serve as tools for violence and dispossession in Palestine. In both their individual practices and work with Depth Unknown, they have researched and explored not only a critique of Israeli occupation and settler colonialism, but, first and foremost, the vocalisation of a Palestinian-driven archaeology and imagination of space. Working in Silwan and Sebastia – Palestinian communities in East Jerusalem and the West Bank, both of which house Israeli-controlled archaeological sites – they have formed wide circles of collaboration and participation, inviting us to rethink spatial-practice-led research, art and political action. In the conversation that follows, we spoke of the past but predominantly of the unfolding political present and the urgent need to rethink the future.

***

Ariel Caine To quote a question asked by Depth Unknown, what does the ground of Palestine say? How can new modes of architectural and archaeological practice allow us to be more attuned to what the ground in Palestine has registered?

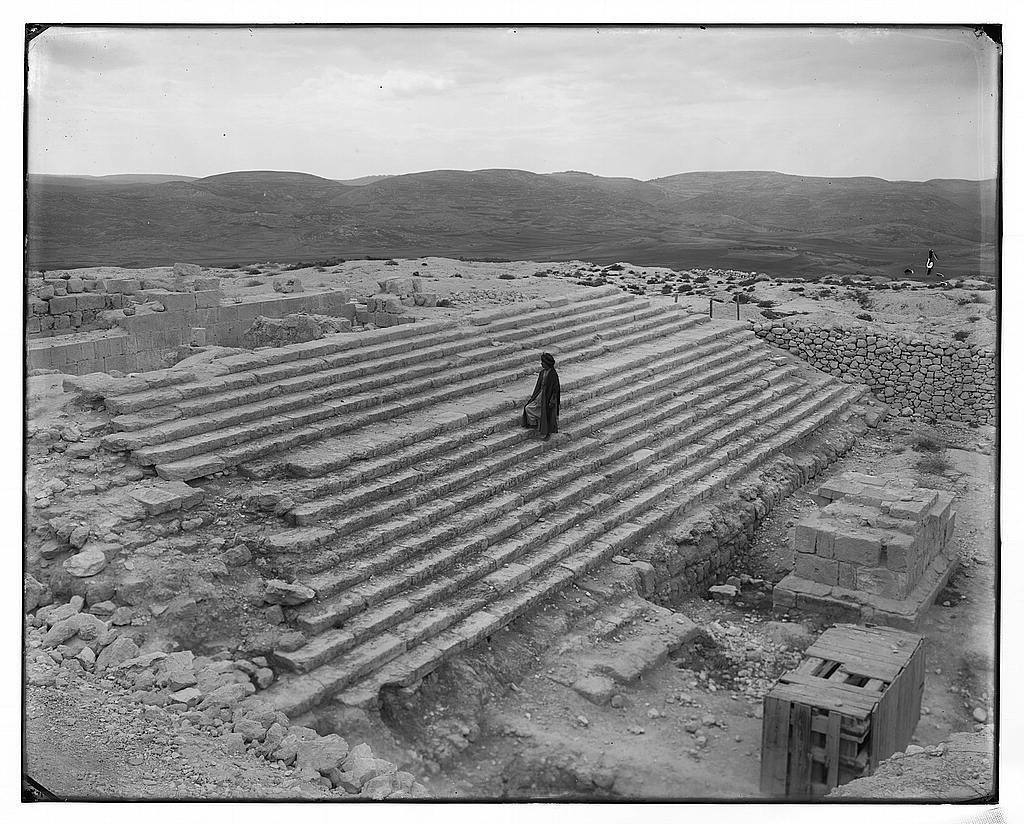

Dima Srouji Our collective started in late 2018, when we were commissioned to work on the Sharjah Architecture Triennial Project. I had been working on Sebastia for an art residency in 2018 and I grew up going there with my family. I realised, during this residency, how much it has changed over the years, and how much it had been affected by the occupation. I thought at the time that Sebastia would make a great case study. So I invited Silvia, an archaeologist and anthropologist, and Dirar Kalash, a sound artist, to start thinking collaboratively by linking multiple disciplines together.

Silvia Truini Archaeology, sadly, is a child of power. It arrived in Palestine with Western imperialism, and it remains very colonial. All archaeological activity, everywhere, is regulated by specific laws of the state. The ground of Palestine and the material that it contains are regulated by the Israeli 1978 Antiquities Law, which was inherited from the British Mandate period, but subsequently enhanced. The fact that that law was passed after 1967 [the Six-Day War between Israel and a coalition of Arab states, which saw Israel seize the Golan Heights, the West Bank (including East Jerusalem), the Gaza Strip and the Sinai Peninsula, ed.] is indicative, because that law serves to deal with Palestine’s past in a very specific way. In the West Bank and Gaza, the laws currently enforced are really an accumulation of British Mandate law, plus Jordanian or Egyptian law with minor amendments. This, together with the political and administrative fragmentation of historic Palestine, generates a fragmentation in terms of how archaeological grounds are dealt with. When it comes to archaeology, if you want to act on the ground in any way, you need to ask for a permit from the authorities. The same goes for when you find artefacts: you must handle them according to the provisions of the law. Archaeology has domesticated a traditional Palestinian way of dealing with ground and artefacts within these legal frameworks, such that it cannot be easily adjusted and the grassroots participation is severely limited by the constraints of the law. Its colonial character can be mitigated, but probably never fully subverted. Archaeology itself is limited, which is the added value of creating bridges with other professions such as architecture and art.

“Archaeology’s colonial character can be mitigated, but probably never fully subverted. Archaeology itself is limited.”

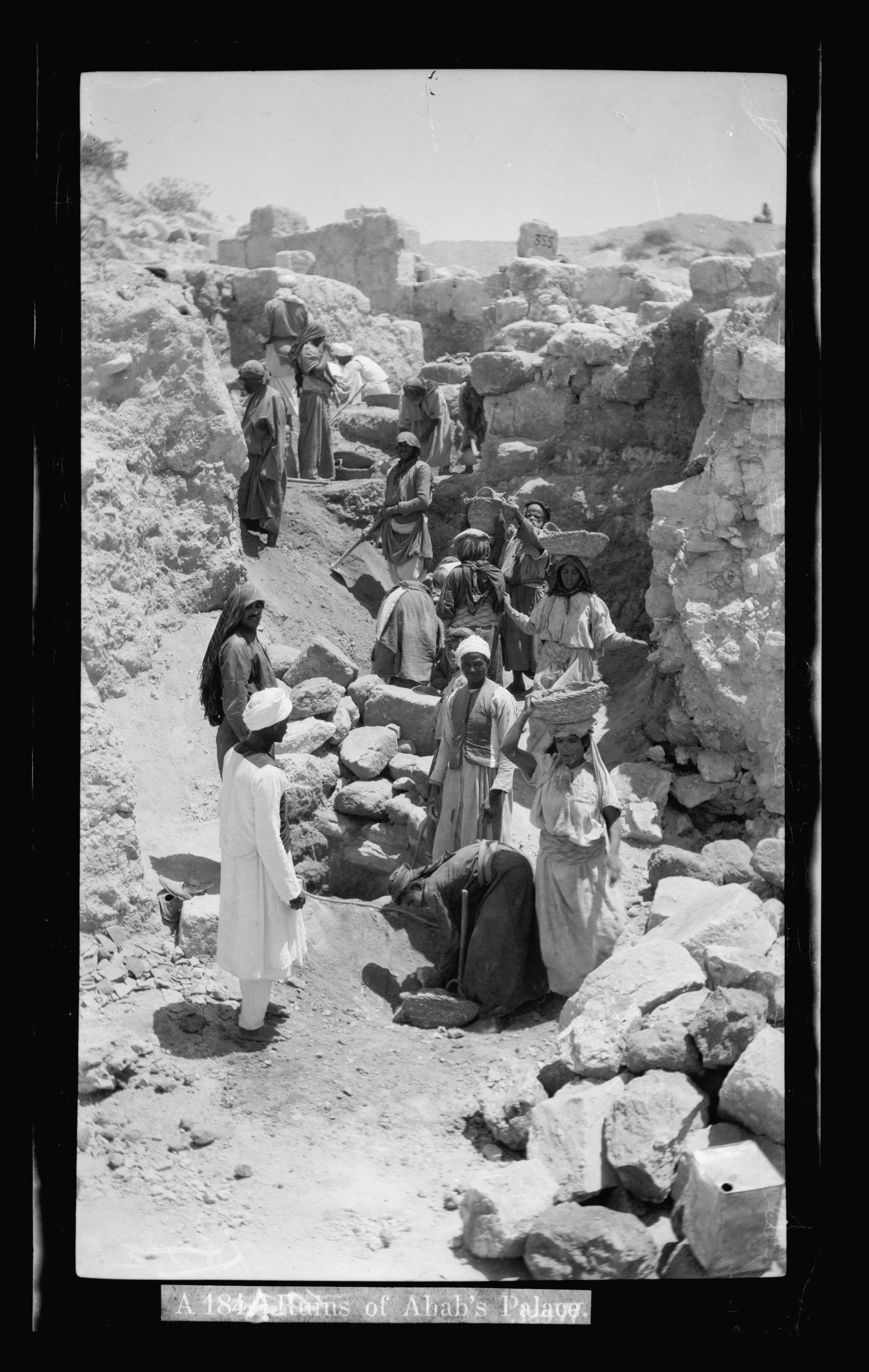

Dima Sebastia was our first case study for these ideas and it took us quite a few years to gather all the data and build our networks on the ground. We met one of its residents, for instance, who owns the Al-Kayed Palace, and is very historically knowledgeable about not just Sebastia’s written history, but also its oral history. His grandmother for example, was one of the people hired as a labourer during the excavations in 1908 [a project led by Harvard University that used Sebastia locals as cheap labour to excavate the land, ed.]. There are a lot of stories like that there, which we wanted to make sure we archived. Obviously over the last few months, since the revolution started up again, if you want to call it that, Silwan has been on our minds, but the reason we initially decided to focus on Sebastia was that it felt more urgent. Sebastia is earlier in the process, whereas Silwan is maybe 10 years ahead in terms of the ways in which the occupation has transformed it. There’s already the City of David tourist attraction in Silwan [an archaeological site speculated to constitute the original settlement of Bronze and Iron Age Jerusalem, ed.], which has massive amounts of funding coming in. It’s almost foreshadowing what could happen to Sebastia. We’re currently looking at surveillance in archaeology, for instance, and the idea of people and objects both being watched in archaeological sites.

Silvia There are so many intersections of archaeology with landscape, including surveillance. Usually, the discussion of archaeology around surveillance is very narrow and based on balancing the preservation of the site: how do we prevent the site from being damaged by tourists, while at the same time providing the best tourist experience? The scope of the conversation is how to maximise the experience of paying visitors, whereas there is almost nothing about the broader surveillance of specific social groups that live around or inside archaeological sites. These archaeological issues can sometimes be considered counter-intuitive, because we are so used to thinking that archaeology is all about the past that we forget the present and the future. But those are key functions of archaeology too.

Ariel Silwan is an interesting site within those parameters of surveillance.

Silvia Silwan has been under consistent pressure from settler NGOs for years. So there is the Ir David Foundation or El’ad, for instance, which is interested in expanding a Jewish-only residential settlement and has been doing so by obtaining the management of the archaeological area. This continuous expansion is foregrounded by increased surveillance and, in turn, brings more surveillance after each step. As an established policy, the state gives, and this is their wording, Jewish citizens living in Arab areas paid-for protection for their own safety: guard posts, guards, cameras and all this kind of apparatus. But also, surveillance prepares the expansion of settlement, because you need to know what the situation is – you don’t parachute yourself into a situation you don’t know. So surveillance is a sort of enveloping case – it embraces the settlement activity before it happens and it’s reinforced after it. Sometimes it passes unnoticed because of how the cameras are placed respective to the archaeological sites – they are perceived as being in connection with the protection of the antiquities, and not so much to do with policing and surveillance of the Palestinian population. Correct me if I’m wrong, Dima, but a few months ago a new police station was also opened at the very edge of the archaeological site in Sebastia.

Dima About seven months ago.

Silvia It’s in an area that is classed as an archaeological zone, but it’s also a public space which the people of Sebastia have always engaged with. It was also – traditionally, historically and presently – used as a marketplace, a parking spot, a playground and before that it was a threshing ground. So it had this history of use and engagement, but now there is a police station there. There is this perceived communication that the Palestinians are inherently dangerous to the settlers and, at the same time, an idea of conveying to the settlers that they are being protected against that danger through complex surveillance and policing.

Dima It’s important to note that as tourists go into the City of David, as they call it, they’re coming in from higher ground. As they arrive, they go through the tourist attraction, which is a new addition developed on top of the archaeological site, and then they move towards the edge of the cliff looking over Silwan where you have this theatrical performance space. It presents the archaeological site almost as if it were a stage, with everybody sat with their backs towards the village. Then you have guides who are not archaeologists, but rather religious tour guides, performing a particular narrative to an audience of mostly Zionist settlers and tourists, as well as the birthright buses that come to the sites. So there’s this idea of orientation, which we’re playing with a lot in our practice – they’re physically orienting your body to the archaeological site and away from the village, and they’re also orienting the cameras away from the archaeological site to the village. The tourists are watching archaeology, but the surveillance and the cameras are watching Palestinians. We also think about the way in which things are labelled and categorised. The terminology is also being censored and watched – conceptually, it’s reframed to cater to a specific audience – and that is definitely not a Palestinian audience.

Silvia So instead of things being labelled “Iron Age”, for instance, you would have “First Temple period”, which is the traditional religious chronology of biblical origin.

Dima It’s a constantly shifting form of language, as well as a constantly shifting orientation of the body and lens.

Ariel The expansion and entanglement of the City of David into Silwan takes place through the manipulation of the spatial layers, controlling sight and movement, as well as the levels of opacity and erasure of non-Jewish presence. This is achieved through the use of things like archaeology, architecture and landscaping of the site, but also with the use of language as you both mentioned. A section of my PhD focused on Silwan, and examined the use of optics in the site. I looked at the ways in which El’ad was directing the excavations of various sections of archaeology, while burying, bypassing or erasing parts of the village – that may take place through the routes by which people are led through the site, the excavation lines, or through the landscaping and gardening that literally hides the remaining Palestinian houses still within the City of David. But there are different types of archaeologists working on these sites.

“I grew up several hundred metres from Silwan, I know the City of David well, yet only in recent years saw and acknowledged Silwan.”

Silvia There’s an established framework in the specialised literature that articulates a substantial difference between the so-called settler pseudo- archaeologists and the university/state function of secular archaeologists, which runs along the lines of inaccurate/accurate, bad/good, politically motivated/ objective. In my analysis, I try to take the point of view of the Palestinian people of Silwan. I want to understand what archaeology does, more than what it says it does. Archaeologists tend not to acknowledge the colonial present of archaeology much. They’re very willing to go into discussions about its colonial legacies or imperial origins, but when it comes to talking about the colonial present of archaeology today, everybody gets very defensive. By contrast, I want to take the point of view of people who are not professionals, who do not have a formal education in archaeology, and who are just on the receiving end of all these archaeological operations, be they operations led by El’ad and the rest of the right-wing, religious-aligned groups, or be they the University of Tel Aviv or the IAA [Israel Antiquities Authority, ed.]. Palestinians are still on the receiving end.

Ariel As you say, those distinctions don’t help when it comes to the question of rights to the ground.

Silvia When the excavations in Silwan started they were privately funded, and they relied on enthusiastic scholars who were ideologically motivated. Those excavations were then criticised by Israeli secular archaeologists as bending facts for the sake of religious and political narratives. Eventually, the IAA itself started to excavate in Silwan, and went from overt opposition to something like a compromise solution in which they now work together. So the question is, how did the IAA turn 180 degrees? Is it likely that the entirety of this good, methodologically solid Israeli archaeology has become aligned with the so-called pseudo archaeology of religiously oriented settlers? The answer is absolutely not, because the excavations of the IAA are state of the art. They’re providing a better interpretation that is more methodologically accurate. But does it improve the situation? Does it contribute to better representation of all local stakeholders? Does it include the Palestinian people of Silwan more? The answer is always no – there is no substantial change. Settlement has not stopped, and the kind of history that is being portrayed in the archaeological park is not more inclusive. So in regards to this dichotomy between secular archaeology and religious archaeology, the bitter conclusion that I have to come to is that it just obfuscates the fact that Palestinians do not have a stake in all this. The Israeli archaeological sphere saturates all the possible space for discussion, and while there may be two different kinds of Israeli archaeology battling for the truth of Silwan, for the truth of what happened in Palestine and for the truth of the ground in Palestine, where are the Palestinians? They have no space because everyone is occupied by this split between religious and secular. Zionist thinking generally constructs itself with internal dichotomies between secular and religious, but it’s a way of taking the Palestinian other out of the discussion. Neither archaeological practice fully accounts for what the Palestinian people suffer, nor for how Palestinians understand the past of their village.

Ariel As an Israeli growing up in Western Jerusalem, I can – sadly – say that life was so confidently centred around the Jewish Israeli presence, culture and language that there almost seemed to be no Palestinians. I grew up several hundred metres from Silwan, I know the City of David well, yet only in recent years saw and acknowledged Silwan. Even if one is relatively politically aware, the slowness of the violence through which this process is taking place and the depths of its normalisation within Israeli society mean that there is a deep de-politicisation and naturalisation of the urban environment, including, of course, within the areas of occupation. You have these extreme right- wing ideologists like Gush Emunim going to Sebastia and establishing a settlement [Gush Emunim was the group that led the religious settlement movement, ed.], but in the Israeli ethos we also have Yigal Yadin and Moshe Dayan making their own collections of archaeology [Yigael Yadin (1917-1984) was an Israeli archaeologist and politician who led a number of excavations; Moshe Dayan (1915-1981) was a military leader and politician who used his position to loot antiquities – upon his death, the Israel Museum in Jerusalem paid $1m for 1,000 objects from his collection, ed.]. And you have a series of generals, heads of state and presidents re-articulating the past in order to enable a narrative of continuity of Jewish presence in the region. But only a marginal minority acknowledges and prioritises Palestinian life in Silwan. When petitions were brought to the courts that the foundations of people’s homes in Silwan were being undermined by the archaeological tunnels, the judge responded by saying that there was no proof or that the proof was not enough to necessitate stopping culturally significant finds, such as those that come out of the digs. The professionalisation of the practice only works to solidify this, in that to most Israelis and, I believe, also to most international eyes, it makes the digs legal, scientific and to some degree ethical.

Silvia You’ve hit the nail on the head – that’s exactly what it does. Whatever happens in the name of science gets a general stamp of approval, because science is believed to be objective and apolitical. But archaeology is one of those social sciences that like to pretend to be an exact science because it uses instruments of the hard sciences. So we use mapping and quantitative research methods, and we use lab technology – so a lot of science is used by archaeology, but that doesn’t mean that it’s an exact science. Eventually, the results are heavily interpreted and build narrations about what happened in the past. Of course, there are also doubts about whether exact sciences are apolitical, but those doubts are especially strong in the social sciences, which are inherently political because they come from a society, belong to that society, and express that society’s needs. What archaeology does is present something as if it is objective, which means that it is seen as a sort of absolute non-political truth that cannot be disputed because it comes from this ivory tower of science.

Dima There is also the expectation from the funders themselves for excavations to bring value to the funding institution, which has been the case for 100 years. The Harvard excavation in Sebastia in 1908 was funded by a Zionist, Jacob Henry Schiff, who was the founder of the Harvard Semitic Museum [in 2020 this institution was renamed the Harvard Museum of the Ancient Near East, ed.]. He became quite frustrated towards the end of the excavation because the Ottoman Empire dictated that they weren’t able to take the artefacts they excavated back to the Semitic Museum. They were only able to keep the diaries of the archaeologists – a lot of the artefacts ended up going to the museum in Istanbul – and those diaries reveal the funder’s frustration and desire to claim ownership of the artefacts, as well as of the narrative that was being excavated. That expectation is still the case in the City of David today – to excavate and claim the value of the narrative that’s there. Obviously, they now have the support of the state too, so there are no blocks in this case as there were in the past with the Ottoman Empire. It’s a much smoother ride.

Ariel Can we re-repurpose the methods and tools of archaeology and the state? With Ground Truth, a project that I led with Forensic Architecture [a project exploring the village of al-’Araqīb, which has been demolished more than 170 times over the past 60 years, and which Israeli authorities claim did not exist prior to the 1948 establishment of the state of Israel, ed.], I was in the Naqab desert. In that environment, you’re talking about ongoing erasure through physical displacements, as well as the afforestation projects of the KKL [the JNF-KKL or Jewish National Fund was founded in 1901 to buy and develop land in Palestine for Jewish settlement, ed.], which also owns land in Silwan. So we were working with activists from al-’Araqīb and helping members of the village create community-led mapping of the land using various constellations of media, media practices and testimony. By using, modifying and repurposing different tools normally associated with the state, as well as introducing DIY or low-technology practices, such as kite aerial photography, we were able to not only challenge the dominant claims of the state andits experts, but also, together with the families, begin proposing a different way of thinking and practising surveys, photograph and politics from the perspective of the Palestinian Bedouin families. The most important part for me in all of this was building a community of practice. What form of community practice could you both imagine there to be around archaeology in Silwan or Sebastia? What form does that take and how does that equip people for the long run, because it’s a very slow process of resistance?

Dima Since the Oslo Accords [a pair of agreements between the Israeli government and the Palestine Liberation Organization that were signed in 1993 and 1995, dealing with questions of borders, settlements and Palestinian autonomy, ed.] Sebastia’s archaeological site has been split into Areas B and C. Area B is managed by the Palestinian authority and the mayor of Sebastia, whereas Area C is untouchable to that community. But Area C covers almost the entirety of the archaeological site, so that has now become an Israeli national state park and with that comes zoning loopholes. So there are military archaeologists, funded by the state, and settlers who can come and go into Area C, bringing bulldozers and guns with them – that is something you don’t see anywhere else in the world. Area B is partially under Palestinian control, which means that it’s a living and breathing city, but even Area C, as an archaeological site, is still a living and breathing public space. Because of the density in Sebastia and the way that zoning laws work around there, public space is very hard to come by, so the archaeological site has always been a space where kids can play football in the Roman forum. Historically, that site functioned as a public space where kids could play and men could hang out and smoke shisha, and the more forested areas let lovers walk down the street as teenagers, where no one would be able to see them. It’s not an area that’s frozen in time and it’s not an archaeological site that’s partially excavated – this isn’t a dead space.

“As Palestinians, we don’t understand archaeological sites as being of the past. They are specifically part of our lineage and history, and we value them.”

Silvia When you said that Silwan is 10 years ahead of Sebastia, that is very true. The archaeological site of Silwan was once all public space, which is still very much alive in the memory of the generation of people who are now in their 40s. They remember when those spaces were available for public use and how they used to go into the ruins or use those spaces before excavations resumed in the 1990s – people still feel that loss. Let us not forget that the excavated areas in Silwan lay between Palestinian houses, so there have always been pathways for Palestinians to move from place to place that crossed through those areas. Over the course of the last 10 years or so, all the excavated areas have been progressively fenced in and closed with gates, the opening times of which respond to the opening hours of El’ad’s park and not to the Palestinian patterns of movement. In some areas, like the water sources, Palestinian access must now respond to the commercial dynamics of this tourist attraction, which means buying a ticket. That is a massive social wound and I have collected the testimonies of many people who are completely crushed by the fact they have lost the public space that they used for weddings to a massive excavation, or that they have lost access to the water sources of the village that their grandmothers used for water and which became a swimming pool in the summer. These changes mean the disaggregation of the social network.

Dima What that means for Palestinians is that we don’t understand archaeological sites as being of the past. They are specifically part of our lineage and history and we value them, whereas a lot of tourists come in thinking, “Wow, this is really ancient.” In speaking to a lot of the kids who collect pottery shards from the Sebastia site, the way that they talk about them isn’t, “This is part of my heritage” or “This is part of my history and I’m romantically, emotionally connected to these things.” It’s more, “I’m from here and these are cool things that I’m collecting” – almost as if they’re at the beach collecting seashells. There’s something really freeing about that – it’s those objects’ presence in the moment that is valued, whereas the state values lineage. So a lot of the anger that’s coming out of Sebastia today is around not having the right to live in the moment and not being able to use the public space. We don’t question or push our indigeneity.

Silvia Sebastia is still in the very embryonic stages of this development, but in Silwan this has already happened and its impacts are devastating. And whatever the people decide they want to do in terms of resisting or counteracting this is necessarily symbolic, because you need permits to materially act upon archaeological areas, and everything that happens in the archaeological site is legal. This doesn’t mean it’s fair, but it is legal, and its effect on Palestinians has been wilfully unacknowledged. Unfortunately, this is just yet another one of the sore spots of the situation. On top of the dispossession, on top of the impending demolitions, on top of the tunnelling beneath houses, there is this crushing of the social and symbolic spirit – the connection between people and place. It’s a very refined alienation of the Palestinian people from their land.

Dima As a Palestinian and someone who grew up going to Sebastia as a tourist, we’re fighting for the rights of the future generation and making sure that Sebastia doesn’t end up where Silwan is today. So Dirar Kalash, the sound artist we work with, is recording Sebastia’s underground voids, in which you can sometimes pick up the sounds of kids playing football, just as you can also hear the bulldozers or the birds chirping in the trees. The site itself is incredibly complicated, but also somehow very simple. It’s just a public space and there’s something beautiful about that. We want to try to use Dirar’s recordings and all the data that we’ve collected to shed light on the living and breathing part of Sebastia, rather than focusing so much on the underground, which is the spotlight for archaeology. So, yes, we want to highlight the ways in which the system is oppressive and, yes, how bulldozers and machine guns are there, and, yes, how settlers are burning olive trees that will never grow back, but we also want to move a step beyond that and think about what public space means in Palestine today How do we, through policy, save public space and actually create a soccer field for the kids, or provide funding for a youth club. There are interventions that are on the periphery of architecture and archaeology, but which are very much relevant to daily life in Sebastia.

Silvia The huge question is: how do we make a better archaeology without losing archaeology? It’s a difficult question, because archaeology is so inherently colonial, and it’s great that there is now an open discussion in archaeological academia about decolonising archaeology, but it’s going to be hard because archaeology is a method. It’s a way of analysing things or an instrument. But instruments in themselves are neither good nor bad. A hammer is a hammer – the fact that I can use it to hammer a nail into a wall to hang up a picture, or else to smash someone’s head, doesn’t make the hammer inherently good or bad. The problem, however, is that the hammer has the capability of hurting people. So the problem is, do we still hammer nails into the wall if we also have people’s heads lined up all over that wall? Do we still want to hammer nails or should we try to do things differently?

Dima We’re thinking about archaeology in a way where you’re thinking about excavating the ground as a means to better connect with the land and our own individual memories, but also the collective memory. Talking to people from Sebastia, they speak about their connection to water and the absence of water, and to the polluted water that’s there today because the Israeli settler factories produce cosmetics and leather, and then pour their wastewater into our fields. It’s not just about the lands being polluted, but it’s also a lot about what is no longer there. It’s about absence and recognising the memory of what used to be there. It’s about being able to walk down into the valley, filling your jug with water, and going back up to the house. That absence and the memory that remains is incredibly powerful.

Ariel It’s not just a matter of the public space being cut off either. The plans for that area include a new public park, so there’s a whole green belt that’s also threatening to demolish more parts of Silwan. A lot of this is the process of terraforming, of reconfiguring the earth around the space and creating a future that is, in my mind at least, done in a way to not just banish these places into the realm of memory, but to not even allow residents to imagine themselves as being a part of that land. There’s an estrangement that is starting to happen. Speaking to Aziz al-Tūri, a man in al-’Araqīb, he gave the sense that the landscape is transforming under their feet, in front of their eyes, and they are literally starting to get lost in their own land, becoming unable to imagine that land as theirs, not able to pass on those memories in connection to the space to his son, his daughter. It’s this inability to actually connect yourself to the place from which you’re from.

Dima There is a nostalgia that captures every Palestinian. There is this running joke about Palestinians being excessively nostalgic and there’s a film that Elia Suleiman made called It Must be Heaven. There’s only one line in the whole film, where Suleiman is at a bar in New York drinking with a Lebanese man. And the Lebanese guy looks at him and says, “Everyone drinks in the world to forget and only Palestinians drink to remember.” There is this idea about memory that is so embedded in our psyche, which I like to call nostalgic paralysis. There’s definitely a nostalgic paralysis that Palestinians carry with them as a remembrance of the Nakba, which is never over. There’s an ongoing Nakba that continues in our bodies, and which continues from one generation to the next. Every single Palestinian has this story from their grandmother or great-grandmother that stays in our memories, in our bodies. Whether you’re from Silwan, Sebastia or any other Palestinian city, you carry their stories with you.

“The only thing that the collective and I are trying to do is continue the conversation, because there are hundreds of sites that we need to look into.”

Ariel During one of his artist talks, John Akomfrah spoke about the Caribbean sociologist Orlando Patterson’s notion of life in the absence of ruin as a part of the state of diaspora [Patterson has explored the poet Derek Walcott’s assessment of West Indian consciousness as being informed by “an absence of ruins”, stating that “To be a West Indian is to live in a state of utter pastlessness”, ed.]. As this slow erasure happens in Palestine, this confiscation and blocking off and transformation of the lands, the erasure of pre-1948 as well as of the post-1948 ruins, people are increasingly living in the absence of the remains of places that define them to some degree.

Dima I really like the idea of an evocative object in the ground – ruins themselves embedding memories and the potential for these space to exist beyond the human being. An archaeological object that’s maybe four or five strata down, contains within itself a memory, with or without us. There’s a lot of safety in feeling that way, because it takes a little bit of weight off of us to continue telling the ground what to say, and having this anxiety around making sure that the ground can speak through us. I like the idea of the ground speaking for itself. And maybe within that idea, there’s this sense of the ground telling its own truth, without archeaologists trying to superimpose narratives on top of it. There is an intensity and debate about the subjectivity and the perception of an archaeologist , so if we remove ourselves from the equation, what does the ground say? That’s why collaborating with a sound artist to try to get the ground to speak was really exciting.

Ariel Part of the changed understanding within my own practice – a change that has taken place very much through learning from people close to me, like the photographer and activist Miki Kratzman and hugely through Eyal Weizman [the founder of Forensic Architecture, ed.] – is how to use, let’s say, my privilege as an Israeli Jew within this system to form networks that stretch and challenge the disciplines of archaeology, mapping, photography and juridical structures. How can we return to the question we started from – that of listening to the Palestinian ground speak? What communal practices do we form? And, lastly, how do you see the connection or collaborations with Israeli Jewish people, for instance?

Dima First of all, the only thing that the collective and I are trying to do is continue the conversation, because there are hundreds of sites that we need to be looking into. Collaborating with multiple institutions, individuals and collectives is really important to get the ball rolling on this investigative work. I was actually in New York over the last four months, which was crazy timing, and the biggest allies during that period were Jewish friends whom I met at protests. It seems to me that there is this new phase, where there is finally a separation in people’s minds between their religion and the way in which they understand Israel. Their relationship to the state is changing very quickly, or at least it is for people in my community. Those people who grew up in Zionist homes, where their families were a big part of AIPAC [the American Israel Public Affairs Committee, ed.] and so on, came to me over the last two months saying, “We’re changing our minds. We’re having conversations with our parents and we no longer relate to the state of Israel the way we did growing up. We understand that our relationship with it does not need to be the way that we grew up understanding it to be.” I’m quite hopeful, actually, that the Jewish community abroad is having an easier time with this than Jewish Israelis. It seems to me that physical separation from the state is useful, because I know a couple of people here who are starting to speak up openly, but they’re having a very hard time. I feel like it’s definitely time for a serious, much more direct collaboration with anti-Zionists in Israel. I just don’t know enough of them.

Ariel There aren’t that many, sadly. It’s also shrinking as a community.

Dima Because they’re leaving or because they’re being converted to Zionism?

Ariel Some are leaving, but there are many levels to this process. On a very small, prosaic scale, I believe for some there’s the need to just conduct daily life. After battling against your environment for decades, at some stage many people feel the need to pull back and say, “Okay, I still have to take my kids to kindergarten or to school. I need to go to work. I need to rest a bit.” They’re no less political intellectually, or even vocally, but in terms of feet-on-the-ground existence it is quite attritional. Just as an anecdote, the soldiers or university students today never lived under a non-right-wing government; most of those within this age range have lived most of their lives under Netanyahu, where leftism, even Zionist leftism, has been equated with a form of national betrayal. There’s also an ideological and political loss of direction for the socialist counter-nationalist leftist political parties and social movements that we can see on a global scale. In the context of the depoliticization we spoke of, all the globally relevant issues that come with the rise of nationalism and neoliberalism are also having a considerable effect on the diminished possibility of a leftist anti-Zionist presence within Israeli society.

Dima The Palestinian community seems quite demanding from the Israeli perspective. I have a couple of friends who are artists living in New York and they’ll say things like, “We speak up about this all the time and a lot of our work is about shedding light on Palestinian craft and heritage.” Well, there’s a little bit of a trick there in terms of talking about Palestinian art and craft history as an Israeli, so how do you navigate that, but also are you still working with Israeli institutions? To them, we look like we’re being quite demanding, and we do have a lot of red lines and there are expectations to not work with specific institutions. So I can imagine how it would be quite hard, not because of identity politics, but just because of daily life to check off all of those boxes and say, “Yes, we will not work with any Israeli institution. We will call ourselves anti-Zionists publicly and abide by BDS [the Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions movement, ed.] regulations.” Those are almost impossible to do living in Israel, but our demands are quite basic at the same time. There’s a long way to go.

Ariel The direction where I’m asking it from is that I have the feeling that, since Oslo, this cutting off between the different societies has led to a huge amount of radicalisation and extremism. Just by the fact that everything is regulated, there’s no flow between different perspectives in communities. Everything is either speaking for one or the other. We need another type of group that can speak across the, let’s say, border and mix the two, not erasing the differences between Israeli and Palestinian members, but forming different constellations or groups of activists, who can keep communication going and allow for different viewpoints that are so crucial in imagining something else.

Dima You’re reminding me of something you said earlier in the conversation, which was about Israelis growing up and not knowing that there is this whole other world that exists in parallel. It is exactly the opposite for Palestinians. You grew up your whole life knowing that you’re occupied, knowing that there is something on the other side that is creating this intolerable life. You grow up looking at settlements across the valley and seeing an apartheid wall in front of your face, and checkpoints, and being treated like a second-class citizen. The presence of Israel and Israelis, at least in a Palestinian life, is so overwhelming. It’s so present and it’s so loud and it’s so visceral, whereas the experience of an Israeli is the exact opposite. It’s almost like there’s nothing there. A friend of mine, who was born and raised in a settlement, moved to the US as an undergrad and then became quite politically radical, completely changing her ideas about the occupation. She went back home to visit family for the first time in 15 years and told me: “I heard the mosque for the first time in my life. And I saw the village across the valley for the first time in my life. I asked my family whether it had been there the whole time and they said, ‘Yeah, it’s always been there. It’s not a new mosque – it’s been there the entire time.’” She was suddenly able to see it and hear the Azaan for the first time in her life. So there’s this sense of seeing and being seen, which is also relevant to the idea of surveillance and who is watching and who is being watched. In terms of collaborations, I think that a big part of it is determining who is doing the labour and who is putting the effort into explaining or crossing the border. The general Palestinian community will say that it’s not up to us to collaborate and not our responsibility to reach out – it’s in Israelis’ hands to make that effort and to approach the Palestinian community with generosity and care and understanding. And it seems like that’s starting to happen. For us, however, it’s a question of how do we make space for that? We also need to be caring, generous and graceful in the way that we make room for that to happen.

Introduction Ariel Caine

Photographs Dima Srouji

This article was originally published in Disegno #30. To buy the issue, or subscribe to the journal, please visit the online shop.