Enzo Mari was a Universe

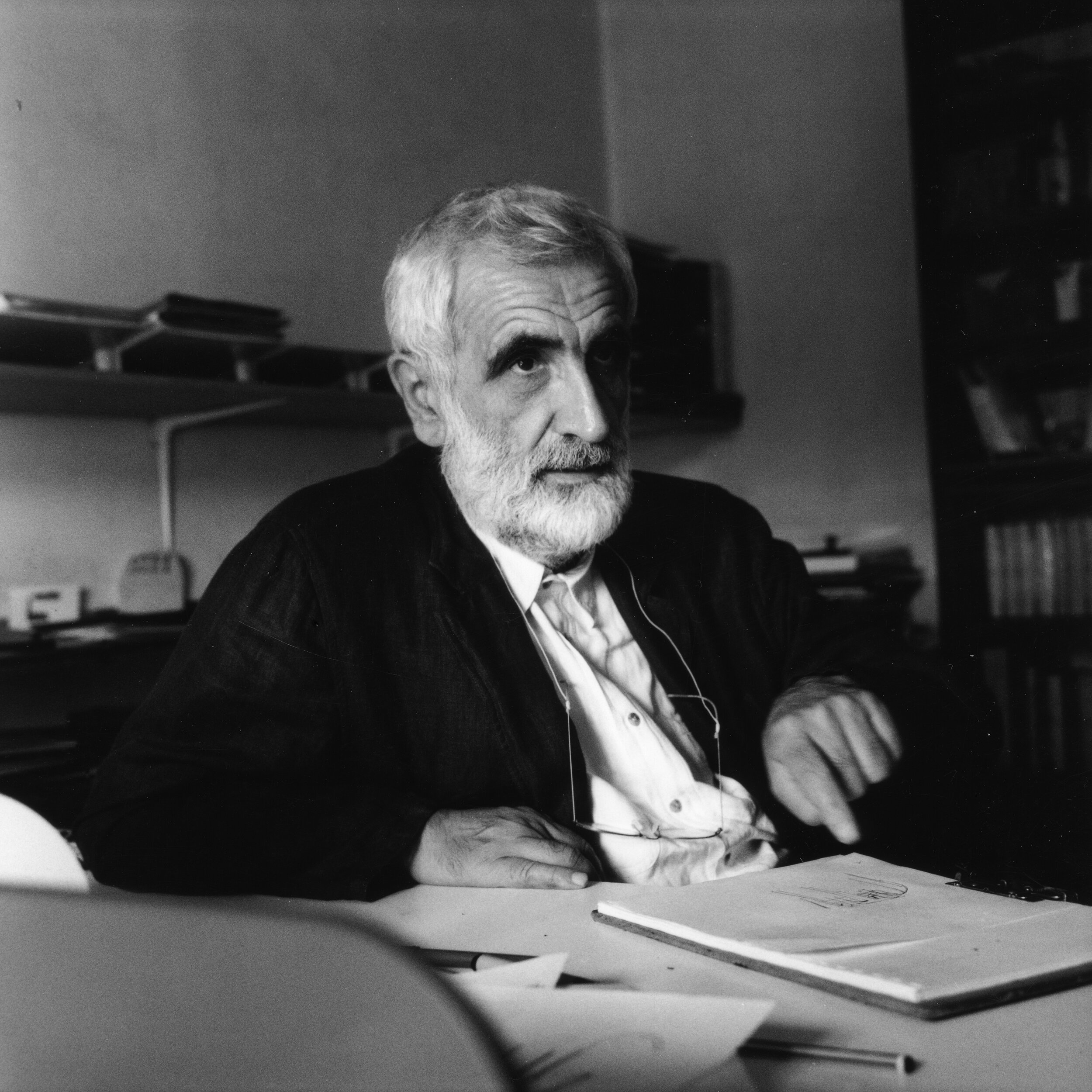

Enzo Mari (1932-2020) (image: Ramak Fazel).

For Disegno’s 10th anniversary, we’re republishing 29 stories, one from each of the journal’s back issues, selected by our founder Joahnna Agerman Ross. From Disegno #28 she chose our roundtable memorial to Enzo Mari.

On 19 October 2020, the radical thinker and designer Enzo Mari passed away in Milan, shortly followed by his wife, the art historian and critic Lea Vergine. Disegno gathered a roundtable of collaborators, friends, students and scholars to remember a figure who was often at odds with the design industry. His assistant Francesca Giacomelli introduces the conversation, which features designers Martino Gamper and Corinna Sy, design historian Cat Rossi, and curators Hans Ulrich Obrist and Lorenza Baroncelli.

I was honoured to work with Enzo Mari for more than 14 years, observing his research method, his revelations, failures, and theses. He had first called me in 2007, asking me to assist with the curation and coordination of Enzo Mari : l’arte del design, an ambitious exhibition held in 2008 at GAM in Turin. After that extraordinary project, he asked me to continue to assist him.

Working with Mari was an enlightening experience. It wasn’t always easy – a sort of monastic training in which I pursued exercises of criticism and utopian thinking. Mari involved me in constant dialogue – endless discussions in which time seemed to be suspended as ideas flowed and hypotheses were dissected, denied or cultivated. These conversations often triggered clashes, but their intellectual exchange was my greatest teacher. Mari jokingly called me the “anarchist conscience” of the studio, because of my critical tendency. But, as he taught us, if we want to change the world, then we need a lucid madness, a faith in utopia, and the critical ability to identify what needs changing.

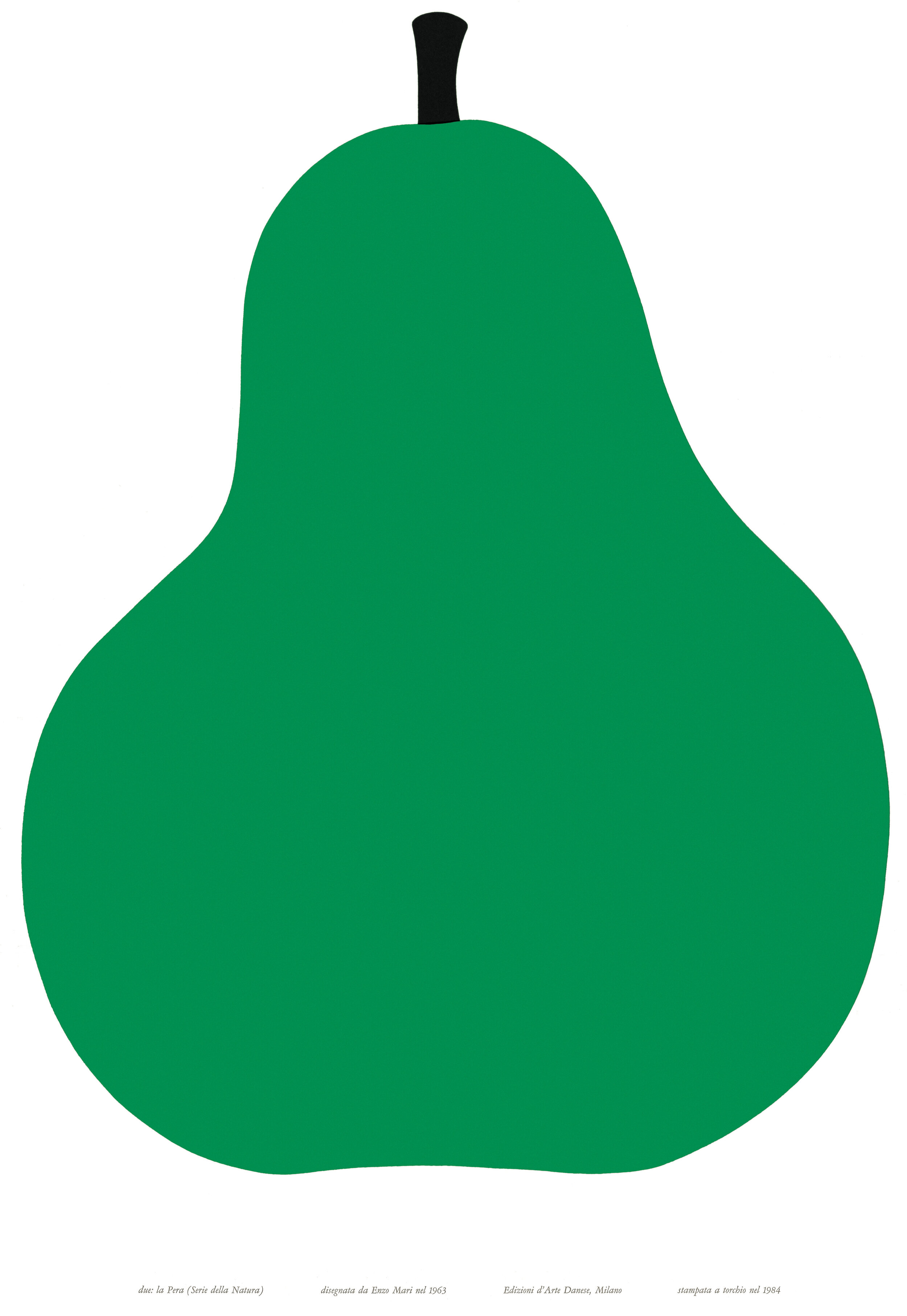

A silk-screen print from Mari’s La Serie della Natura with Elio Mari for Danese (1961).

Mari was a universe. His lifelong project was to transform the world through a socialisation of design. By freeing us from simply being passive consumers

of design, he believed we could reorganise society according to more collectively conscious principles of material and intellectual production. He saw design not as a simple producer of forms for contemplation or consumption, but as an instrument for transformation that needed the active participation of the collective. His ideas for a new form of civilisation were rooted in the cultural and social degradation that he saw around him, and that he fought against his entire life.

In 2018, Mari, his wife Lea Vergine, Stefano Boeri, Hans Ulrich Obrist, Lorenza Baroncelli and I decided to recreate and expand L’arte del design, the last exhibition curated by Mari himself. The resulting show at the Triennale Milano opened on 17 October 2020, and displayed an unprecedented number of works, as well as hitherto unseen archival materials. It also symbolically marks the hand-over of Mari’s archive to the City of Milan, which Mari provocatively said won’t be publicly accessible for another 40 years. As he wrote in Funzione della ricerca estetica (1970): “The meaning of the research will only be understood by the public after a mediation, which will last for at least two generations”. This archive is a complex codified diary in which Mari collected and conserved his projects and wider programme of revolutionary ideas; it is his life’s work, the essence of his research. For Mari, “The research is the design, not the product”. Now we need to rediscover those methods and ideas, preserve them, and celebrate their astonishing transformative potential.

Martino Gamper I met Enzo Mari as a student in Vienna, where I studied in 1994-97. Matteo Thun had been our professor, but he then left and so the college was looking for a replacement. They asked Enzo, but we had no idea who Enzo Mari was. I guess the 90s was anything other than Enzo Mari design – it was Philippe Starck and that whole idea of “form follows fun”. So Enzo walked in and was very charming, but also rigorous and strict. He really left an impression on us from the first day we met him. He was very pragmatic and made us clean out what he called “all the shit” from the studio, because there was a lot of stuff that had been there for 15 or 20 years. It was an interesting way of refreshing the course and, after that, I kept in contact.

“My interview with Mari lasted over two hours. I asked one question.”

Cat Rossi I’m afraid I only knew him from a distance. I’m a design historian and did my PhD on the role of craft in postwar Italian design, and was fortunate enough to interview him. It was an amazing experience because you think you know how an interview is going to go: it’ll last an hour and you’ll ask some questions. This interview lasted over two hours and I asked one question right at the very beginning – that was it.He just gave this magnificent rationale for everything he believed in and how it informed his design practice. It left an impression, that’s for sure.

An installation view of Enzo Mari curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist with Francesca Giacomelli at the Triennale Milano (image: Gianluca di Ioia).

Martino To be honest, we were terribly confused when he came to Vienna, because can you imagine going from someone like Matteo Thun to suddenly having Enzo Mari in your classroom? It was like day and night. He said that if you needed more than three images to show your work, it was basically a bad idea. So we had to really get the essence of our work out there. There were tears and all kinds of disasters as you can imagine, but he was also sort of a father figure. At the end of the day we would go and have a drink with him in one of the Viennese coffee houses, and he would talk and ask personal questions. He was interested in where people were from, what they did, what their background was. And it always ended up in quite a heated conversation where we lost him in a rant. Because he didn’t speak any German, he had to be translated for those who didn’t speak Italian. A friend of mine from Bolzano said, “Okay, well, I can translate whatever Enzo is saying.” I remember that a couple of times Enzo somehow knew that the words my friend was using weren’t right, even though he had no idea about German. My friend was trying to be more polite and using slightly softer language, but Enzo would get absolutely crazy about this; totally mad about small details that were very important to him.

“Mari was a kind of myth for everyone in Milan, as well as all around the world.”

Lorenza Baroncelli He was a kind of myth for everyone in Milan, as well as all around the world. I had the chance to meet him for the first time when Hans Ulrich and I were working on the Swiss Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2014. Hans Ulrich came to Milan and we went to visit Enzo – I remember that I didn’t speak for the entire afternoon. I was so impressed. When we started to organise the exhibition at the Triennale Milano with Stefano Boeri [president of the Triennale Milano, ed.], Hans Ulrich Obrist and Francesca Giacomelli, we spent an entire day in his and Lea Vergine’s apartment, which was the last time I saw him. That last time he was older and more tired, but he was perfect with us and spoke a lot about his career. We expected him for the opening of the exhibition at the Triennale, but he was already in hospital with coronavirus.

Corinna Sy Like Cat, I only knew him from a distance, even though he has been very present in my life these last seven years. When I was studying design I had never heard of Enzo Mari, but as I started to learn about him I became fascinated. I got in touch with him because my former colleague Sebastian Däschle initiated workshops for refugees with Mari’s remarkable concept of Autoprogettazione [a 1974 manual that provided instructions on how to assemble a furniture collection designed by Mari using readycut materials, ed.]. Based on this, we founded Cucula [a project which hosted workshops and produced furniture with refugees in Germany, ed.]. Unfortunately I never met Mari, but he granted us the rights to sell the collection.

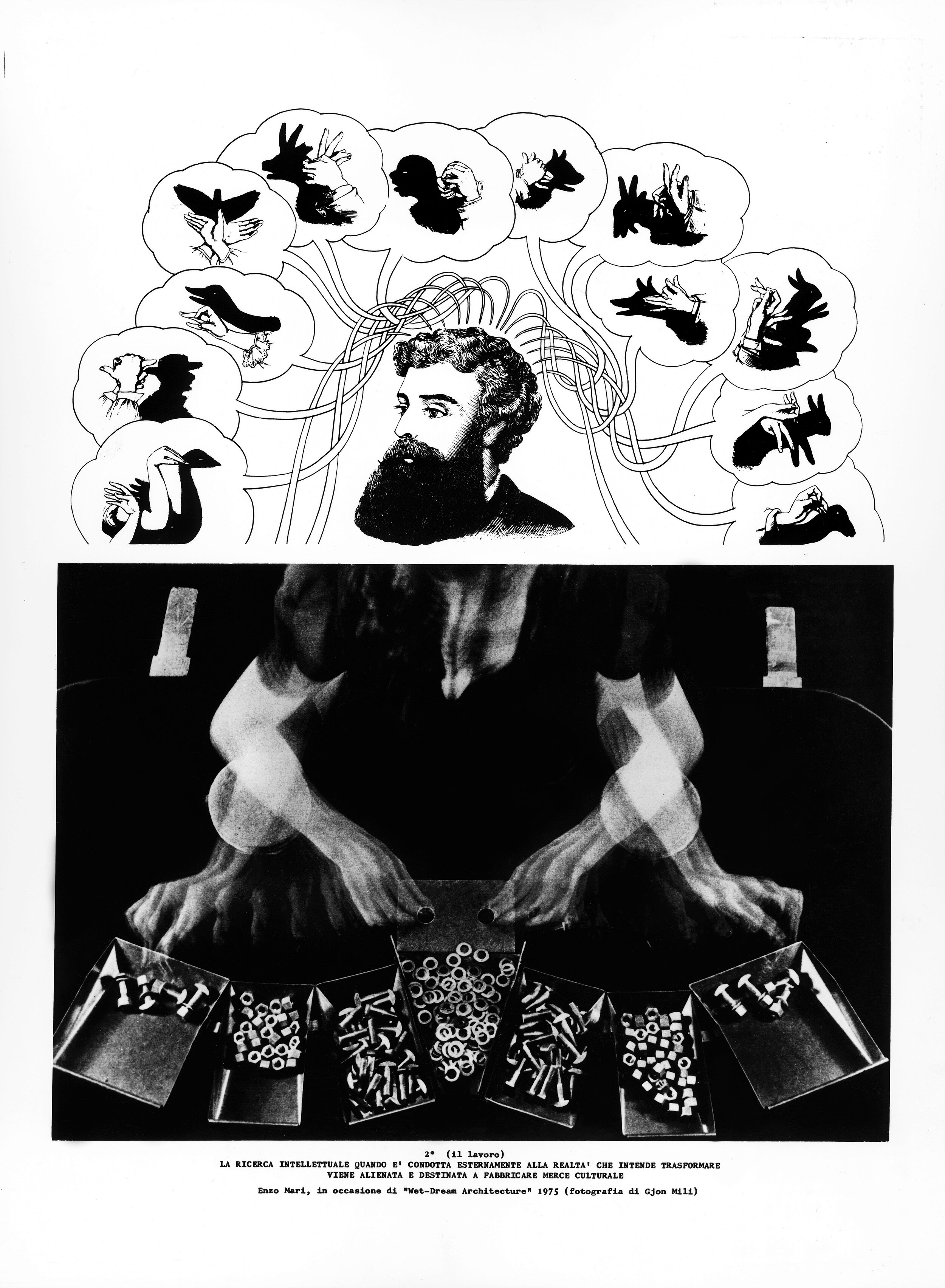

Il Lavoro, a lithograph from Critica della Ricerca Intellettuale Separata, Edizioni Il Lavoro Liberato (1975).

Hans Ulrich Obrist I used to teach at IUAV [Università Iuav di Venezia] in Venice in the early 2000s. At that time I was the curator of the Musee d’art Moderne in Paris, and I would always take the night train to Venice and stop over in Milan to work with Stefano Boeri. Stefano was editing Domus back then and had asked me to do the art pages. So I started to do a series of interviews, which was the beginning of meeting this extraordinary generation of designers in Milan. One day, somebody will have to write a book about the salons at Maddalena and Stefano Boeri’s house, because they were like the great 19th-century salons in Paris. It was a circle where you would have Nanda Vigo, Cini Boeri, Alessandro Mendini, Vico Magistretti, Angelo Mangiarotti, and Achille Castiglioni. At one of these salons I sat next to Enzo and politics really infused his entire thinking: he immediately started a tirade against the design world. I think he was reassured that I was not from the design world and that was the secret of our later close working relationship: his anger wasn’t really directed at me. He invited me to his studio and I was fascinated by his many dimensions. It’s almost like superstring theory with Enzo, because there was Enzo the polemicist, the writer, the intellectual, the furniture designer, the industrial designer, the DIY designer, the exhibition maker, and Enzo the artist, with his extraordinary contribution to Arte Programmata. At the same time, there was also Enzo the pedagogue, the teacher, the anti-teacher, or however one wants to see it. As a result of that, I invited him to come and teach at IUAV, where he spoke for hours against this idea of art, architecture and design education. He basically told all the students to leave the university because it would be a big mistake to continue unless he took over.

Lorenza In the summer of 2018, we decided to host an exhibition on Mari. We felt it was necessary because he’s someone that everyone knows, but to whom nobody had dedicated an important reflection. We knew that he was considering how to donate his archives to Milan, and we felt that the city should reflect on him before that, which is why we decided to invite Hans Ulrich Obrist to curate it. Mari had already said that he felt his work should be closed for the next 40 years. He said nobody was able to understand it because designers are too much under the influence of design’s economic system. He wanted a moment of silence, so we decided to build this last chance to show it before that. Obviously we didn’t know about coronavirus when we decided to host the exhibition, but by coincidence his work seems really important in this moment of transition. He brings the political value of what we do in design back into the debate. There is a sentence in the catalogue where he says that you have to look out your window and see if you like what you see. If you don’t, you need to do something about it. We started working on the catalogue during lockdown and it was interesting to look outside and see everything closed. We realised that we didn’t like what we were seeing right now. It’s really a moment to change our way of thinking.

“We call it Autoprogettazione, but in a sense it was also

Autolimitazione. He could be very limiting.”

Martino In Vienna, I saw him as a designer who had obviously shaped a lot of the post-war generation, but somehow it hadn’t clicked with me yet. I had to

go away and it wasn’t until I was at the RCA in London that I actually came back to Enzo and fully appreciated his thinking. Some of my projects were inspired by

his work and very close to his thinking, but I also got to the limits of his projects. We call it Autoprogettazione, but it was also Autolimitazione in a sense because he could be very limiting – he didn’t really want people to make other stuff out of that project. There was the set of things that he designed, the furniture, and you made it that way or no way. This project, as much as we love it, and everyone gets inspired by it, was also a limitation because it wasn’t necessarily open-source as we know it. It wasn’t that anyone could contribute to it and so extend the catalogue. The catalogue is the catalogue, and that is it. It hasn’t really progressed the way that we live and it’s a very static project in a sense. That’s where Enzo Mari becomes interesting, because he was this character who was divisive, who was cold, but in some ways also very warm. He would give you a lot, and at the same time, he would tell you off and say that your work is terrible. That was just him.

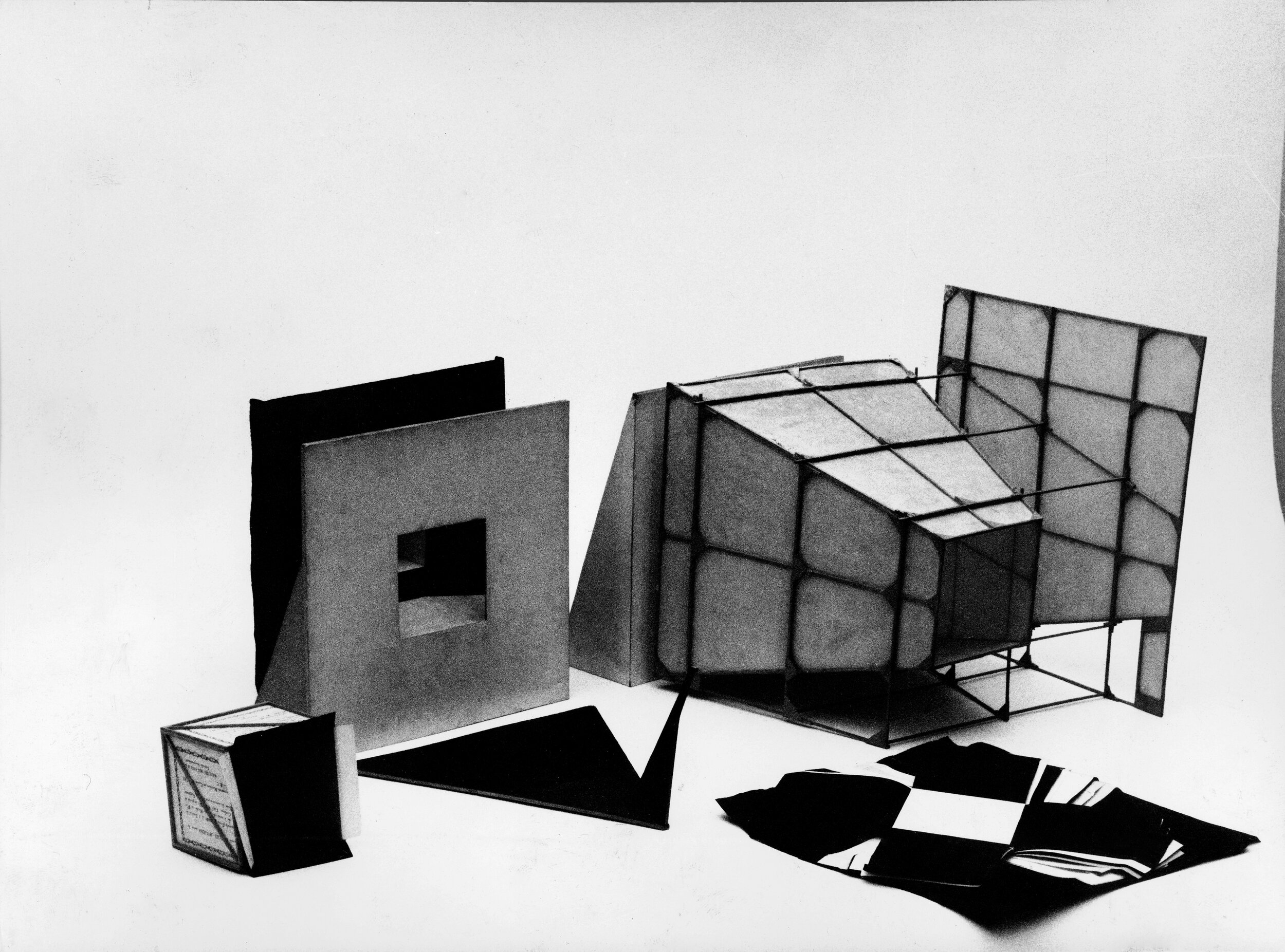

Research materials on volumes and colours in relation to paper and wood (photo: Paolo Monti).

Corinna At Cucula, we started pretty naively with Autoprogettazione. The idea began by offering workshops to refugees living in a camp to use the time and to learn something, and produce furniture they might need. Actually, most of them didn’t like the pieces at first. They said, “No, this is really not a nice style.” We were disappointed, but everybody enjoyed the common experience anyway. The educational background among the participants was very diverse and we were mostly working with people with little to no experience in carpentry or craft, but it was amazing to see how they came to really understand design and how to produce it. One of the participants, who didn’t like the design at first, even ended up building his whole interior based on Enzo Mari’s design. But what was more relevant was it taught us a lot about labour. We wanted to break the stigma surrounding why these people are not allowed to give value to society.

Martino I think young designers go back to his work because he’s one of the few designers who spoke his mind and was very, very clear about intent. There’s

no misunderstanding with Enzo. His Barcelona Manifesto, for instance, is a clear declaration that anything to do with “IT” is basically just an excuse to vomit sellable goods. In our time of Instagram, where really superficial imagery is spread all around the world with very few words, I think we like characters who speak their mind and have a clear vision of what their work is intended for. Maybe he was out of touch, because digital technologies have changed the world: the way we’re having this conversation, and the reason why his work has become fashionable again, is because of how they have allowed people to share things so widely online.

Materials relating to the 1974 Autoprogettazione guide, including a technical sheet, nails and balsa wood panels, photographed in 2002.

Cat I think his legacy and how it’s understood has changed hugely over time. I was a design student in Milan in the early 2000s and he wasn’t really a name that was referenced. But in the last 15 years that I’ve been teaching in art schools, you’ve seen this growing realisation and understanding of how important he is in connection to this growth in political, sustainable and ethical consciousness among young designers. I think he stands out, both now and then, because he wasn’t about ego, it wasn’t about a work being an Enzo Mari project. His was this idea of the designer stepping back from being the figurehead, which I think appeals to young designers. It’s not about them, it’s about what they can do with their design and how, through design, you can endow people with agency.

Corinna I’m now working in the field of social design, and everything I learned from Mari is very valid right now. It’s all about questioning systems and structures; questioning what is being built instead of giving answers within an existing system. As Lorenza said before, if you’re unsatisfied, start a project. That’s how we started Cucula – we were unsatisfied with the situation facing refugees in Berlin, so we started from scratch. We created a workshop, built furniture, and followed that with the concept of teaching and learning together. The project became something of a proposal or even a provocation, but it’s important to create these different models, and to have more experiments which could give an idea or inspire a different way of living together. Enzo once said something about the need to smuggle in moments of research to practice, and that is now burned into my head. This is what we need now: to figure out alternative way of living.

“Enzo said something about the need to smuggle research into practice. That is burned into my head.”

Hans Ulrich I think it’s fascinating to hear from Corinna and Cat, in terms of a younger generation of designers, that it resonates so much. Every generation seems to be inspired by Mari, but in a different way. The complexity of his oeuvre is almost irreducible. There’s so much there that every generation can find something else. So in the exhibition, we have Nanda Vigo, another immense loss to Covid, who created an homage to her friend Enzo using light, reinterpreting his Sedici Animali and Sedici Pesci to create an Enzo “zoo” out of neon. So you have artists and designers of Mari’s own generation who were inspired by him. Then you have Martino’s generation, as well as another generation of designers like Formafantasma, who discovered sustainability and accessibility through his lens. Not only the democratisation of design, but sustainability is another area where he’s a model because his objects were made to last for good. When I was in Milan for Salone del Mobile, I would always ring Enzo and say, “Would you want to come and see some shows with me?” It was always very amusing because he usually never went to see the shows, so nobody could believe it when suddenly Enzo Mari showed up at the design opening. And then, all of a sudden, he would start to scream in the middle of the show about an object: “This is not going to last!” He was opposed to any form of disposable waste of resources and yet he connected it to his passion for transformation.

Enzo Mari’s studio photographed by Mimmo Jodice in 2020.

Cat It’s interesting, because even in the 70s he was talking about how he wasn’t understood. He talked about that with Autoprogettazione, but he also talked about it with its precursor, the Day-Night bed for Driade. That used tubular steel and an aluminium frame to create a very simple sofa bed that was meant to be really cheap, really standard, as an example of the anti-elitist idea of design that he promoted. But he complained that nobody bought it. It was a flop and he just thought that A) he couldn’t get it cheap enough, and B) people didn’t understand it. He would talk about that as being a problem of alienation from a Marxist perspective and a problem of the capitalist system. In a way Autoprogettazione was the next step on from that – you have to hand the tools over to the people. That project was popular in the sense that he got hundreds of letters and hundreds of photographs, and in the front of the catalogue there’s an invitation to send in photographs of what you’ve done. So while Martino is right in the sense that it was closed, he was also interested in seeing how people might be able to express themselves through it. But he still complained that people didn’t get it and thought it was an aesthetic when really it was about consciousness-raising.

Martino He was almost like a master for designers, because no one ever criticises anyone in design. The design world is different to the art world. In the art world, you have harsh critics, and more critical writing, whereas in the design world you have press releases and that’s as far as it goes. Even between designers, there’s very little criticism unless late at night in Bar Basso someone says, “Actually, I think your show is shit,” which is probably more an insult than a critical instigation. The design world is not known for its criticism because it is linked to industry, markets and global companies. It’s always about talking things up and making things look amazing and great. Enzo was one of the few figures who would say, “this is shit”, and we all need to hear that things are shit as well. We can make things as beautiful as we want, but the system is broken. He could already see that 40 years ago.

“He had these connections to utopia, but felt we lived in a difficult time. That’s why he wanted the archive to be inaccessible.”

Cat A word that describes a lot of what we’re talking about is “integrity”. He wouldn’t do something if he didn’t genuinely believe it. He was invited to design one of the domestic environments for MoMA’s Italy: The New Domestic Landscape, this seminal show from 1972, and he refused. That’s quite some commission to turn down. Instead he wrote this catalogue essay where he talked about the fact that designing physical objects didn’t have any significance anymore. It seems so prescient, because we now have more stuff than we could ever need, and most of it is rubbish. In the end, he talked about communication being what he was going to design instead. That’s the really interesting point, because the key to being a critical designer was actually to not engage with processes through which you could get commissions and opportunities.

Hans Ulrich I think he was very aware of his legacy, but he just thought it was somehow a moment that would pass. If you look at his writings, ideas of utopia appear quite a lot. There is a really interesting [issue of] NAC or Notiziario Arte Contemporanea that he [guest-]edited with his partner, Lea Vergine, in 1971. It starts with a proposal from Enzo where he basically asks all the magazine’s participants – and it’s a long list: Argan, Archizoom, Thomas Maldonado, Lea Vergine and Sottsass – to talk about the annunciation of a utopia, or what he calls a “visione utopizante”. It’s really fascinating to see that he had these connections to utopia, but I think he felt we lived in a difficult time, which is why he wanted the archive to be inaccessible for 40 years. He told me and Lorenza that 40 years, in the bigger picture, is not such a long time.

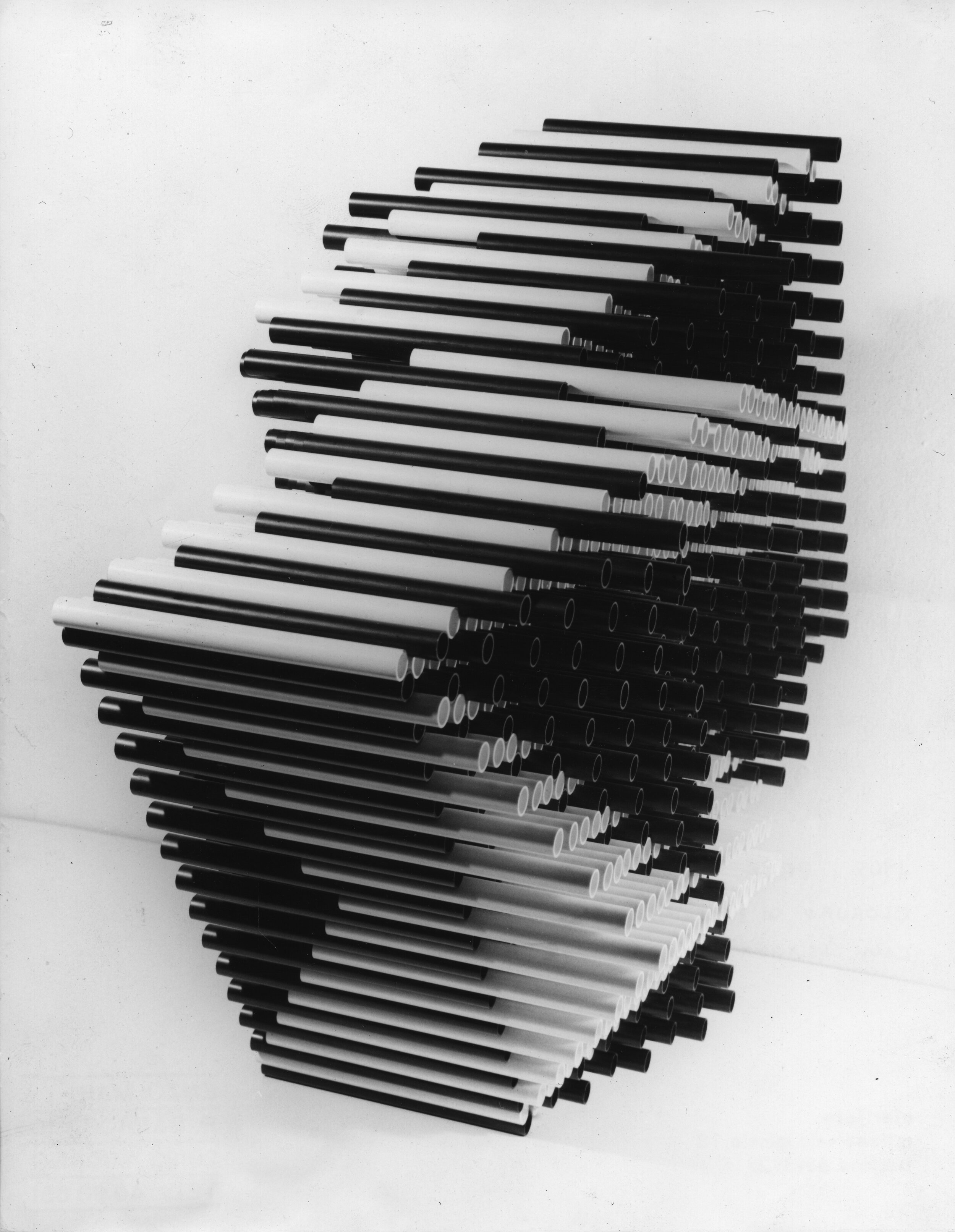

Struttura 783, a structure made from small PVC tubes (1965).

Martino I think he was ahead of his time. He was very much a long-term thinker and I don’t think he saw his thinking as a fashion that would change. It was grounded in the past and he spent a lot of time reading and investigating other people’s work as well. His thoughts didn’t just come from him being a stubborn and very charismatic designer. They are grounded in a lot of other people’s writing and his knowledge of that. I think he saw his thinking as something that’s eternal, and which would hopefully prove lasting.

Cat I don’t think he has ever been overlooked by design, but I always see him as being slightly “aside” from aspects of its history. If you think about radical design, you think of people like Superstudio and Ettore Sottsass and all those figures who always get grouped together, even if falsely, but Mari was apart from that. Although he was political, he was outside of the politics of those other practitioners, but I would say that he was respected. Alessandro Mendini talked about his importance, and critics like Giulio Carlo Argan talked about and understood the political significance of it. Mari caught people’s attention –

he won the Compasso d’Oro four times and featured in the key magazines like Domus and Casabella – but I always got a sense that he had a different position in those social circles to some of his contemporaries.

Hans Ulrich Lea Vergine played a very big role in his thinking. Lea was one of the visionary art critics of her generation. She originally wrote on the same art that Mari was interested in, Arte Programmata, but then she moved into body art and performance, and became a great feminist thinker and critic. She made it a rule that she wouldn’t write about Enzo, so they wouldn’t mix their work. But at the same time, they discussed their work every day. She was, of course, extremely influential on him because she questioned everything and would discuss everything, and vice versa. Her influence on this exhibition was immense.

“That’s a curse for Mari. He may not want it to be about objects, but he also created such beautiful objects.”

Lorenza She followed everything, all the details: looking at the design and discussing everything with Hans Ulrich while smoking her cigarette, because she was always smoking. Francesca Giacomelli was also an important figure, who really has the archive of Enzo Mari in her hands. She knows everything about every object: where it is stored, when it was produced, and has all of the documents, the original files, the original drawings, the text. She’s the person, I think, who will run the legacy of the archives.

Hans Ulrich Francesca has this immense knowledge and there are literally 2,000 projects or more that Enzo created during his career – she knows each of those 2,000 projects by heart. There’s no-one on the planet who knows more about Mari than her, but this idea of knowledge production was key for Enzo. He wanted design to convey knowledge and so the exhibition in that sense also has to be about producing knowledge. It would be absolutely contrary to his idea of work if the exhibition was about objects and not research.

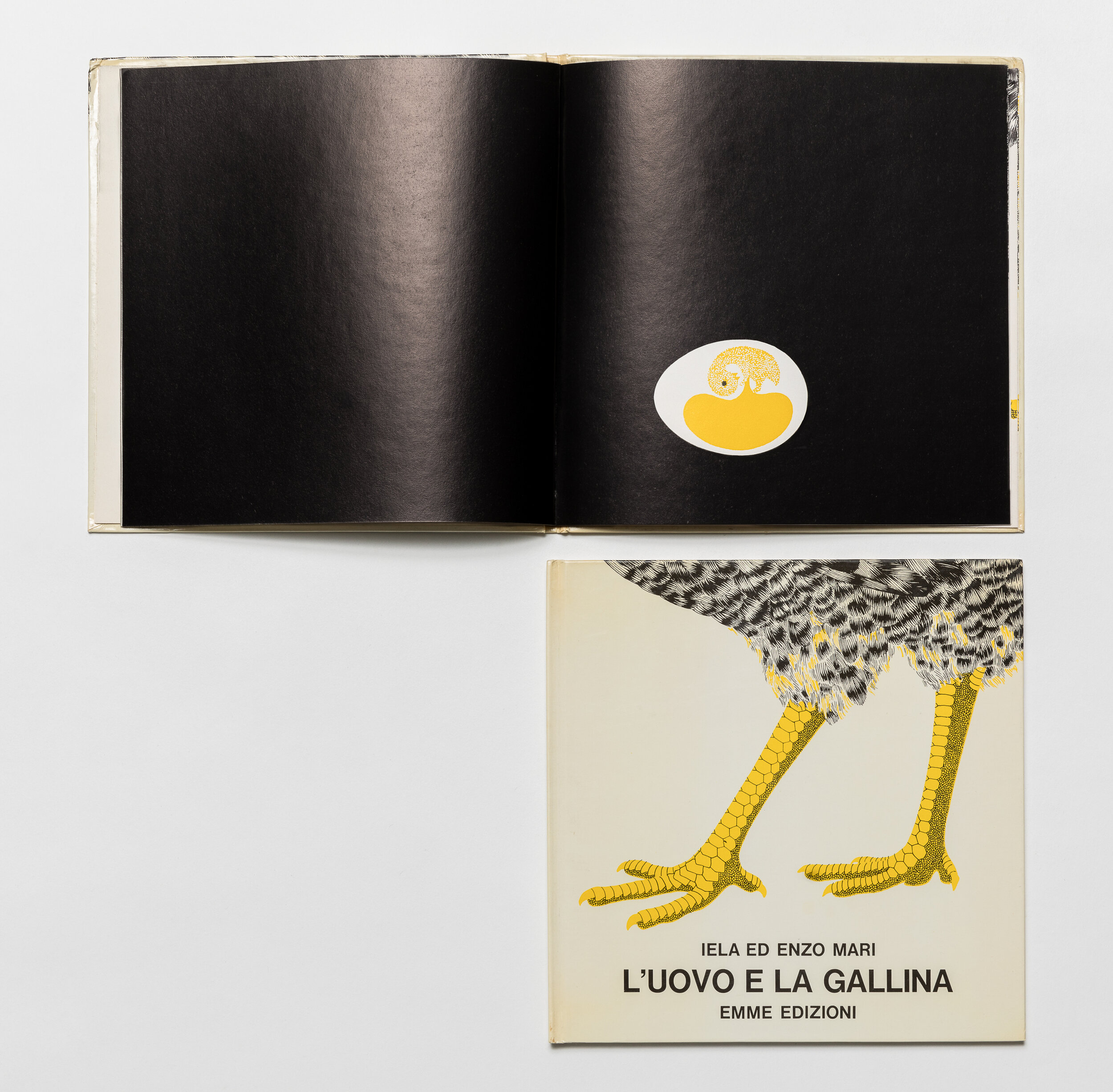

Details from L’Uovo e la gallina, a book for Emme Edizioni (1969).

Cat That’s a curse for Mari in a way. He might not want it to be about objects, but he also created such beautiful objects. Things like the Pago Pago vase,

or all the marble works he did in the early 60s, or the Putrella series, these I-beam [trays] that are absolutely stunning and couldn’t be from anywhere other than post-war Italy. And yet they’re all underpinned by a kind of politics. The skill to marry that politics with aesthetic sensibilities is really something.

Martino He was also a collector and had a really big knife collection, for instance. Whenever he traveled, he would buy knives. I wanted it for my Serpentine show [Martino Gamper: Design Is a State of Mind, 2014, ed.], but he wouldn’t lend it. He was an avid collector of everyday objects – a bit like Castiglioni, but actually a lot more. I don’t know what’s going to happen with his private collections. They’ve never been shown. He must have kept the knives in his house, because I never saw them in his studio.

Lorenza His studio was impressive. It’s going to be destroyed, in accordance with his wishes, but every room was devoted to a topic. One room for materials; one room for prototypes; and all the chairs were stored in the bathroom. The most interesting room was the kitchen, because that was where they produced objects. He was also obsessed with the archive, so created two books with the list of all the objects in the studio and all the documents. He gave Arabic numbers to every object and catalogued everything in those two books. This programmatic system was the basis of his work and I think is the reason why there was no difference between art and objects and graphic design – for him, it was all part of one unique path.

Introduction Francesca Giacomelli

This article was originally published in Disegno #28. To buy the issue, or subscribe to the journal, please visit the online shop.

RELATED LINKS