Design Line: 3 – 9 June

The future has arrived in this week’s Design Line, as Apple reveals its AR headset the Vision Pro and Ikea’s Space10 lab cooks up a flatpack sofa designed with the assistance of AI. Meanwhile, the Barbie movie’s set designers admit to causing a pink paint shortage, and a Polish non-profit wins plaudits for sourcing windows to help Ukraine rebuild.

The future of tech may come with goggle marks (image: Apple).

A vision of the future?

One of the worst kept secrets in design was confirmed this week, with Apple finally revealing that it has indeed been working on an AR headset: the Vision Pro. The device isn’t due out until 2024, and few have actually tried it, but let’s not allow that to stop us from offering expert analysis on Apple’s “spatial computer”. On the positive side, the Vision Pro seems, technologically speaking, extremely impressive, with its three-dimensional user interface responding to a user’s eyes, hands and voice. Conversely, despite a liberal application of Apple’s industrial design polish, there remains an undeniable whiff of dweebishness about the device (although Disegno does prefer its ski-goggle aesthetic to the horrendous smart glasses that have previously dominated the field). More concerning, however, is the question of who this device is actually for. The Vision Pro will retail at $3,499 (with a battery life of two hours), immediately restricting its audience to a select few: more than any previous Apple device, the Vision Pro feels like a 1.0 device that is intended exclusively for early adopters, with more mass market adoption seemingly only sought for future iterations. There is nothing wrong with a technology taking time to bed in, but it’s surely worth asking if anybody beyond hardcore tech bros actually wants AR to take off. Previous entries in the product category from the likes of Meta and Google have hardly set the world on fire, and while Apple will hope that this is because of these devices’ individual failings, there’s no guarantee: in a time ripe with concerns over privacy and digital overload, do people really want to strap their faces into a 12-camera rig and be plunged into virtually-augmented landscapes (that are typically, let’s be honest, crap)? Futurists often speak of certain typologies as having “colonised the future”, meaning that through our experiences of science fiction and similar fields, we develop rigid ideas of what the future should look like, and subsequently work towards those. We want flying cars, for instance, not because they’re actually a good idea (they’re not), but because The Jetsons promised us them (and by God it’s time for George Jetson to deliver accordingly). The longer AR devices struggle to make their mark, the stronger the suspicion will grow. Is AR the future we actually want, or simply the one we’re marching unthinkingly towards?

Barbie and the case of the missing pink paint (image: Warner Bros).

Think pink

There’s nothing like a supply chain shortage to create buzz around a film. Just as there were rumoured shortages of googly eyes after Everything Everywhere All At Once stormed the box office (see ‘A Belief In Kindness’, Disegno #34), now Barbie has blamed itself for a run on pink paint. Director Greta Gerwig’s tribute to the Mattel doll, which stars Margot Robbie in the titular role and is due to hit cinemas next month, reportedly required so much bright pink paint for its set that the supplier Rosco's global stock ran out. In an interview with Architectural Digest, production designer Sarah Greenwood and set decorator Katie Spencer explained that they found inspiration in Palm Springs midcentury architecture and vintage Barbie Dreamhouses to create the set, shrinking everything down in scale ever so slightly to create a doll-like effect on the human-sized actors. Everything was coated so liberally in the fluorescent fuchsia that “the world ran out of pink” said Greenwood. No one could resist such a peachy headline, prompting Rosco to clarify that it wasn’t just Barbie to blame for the paucity of pinkness. “They did clean us out on paint,” Rosco's vice president of marketing told the Los Angeles Times. “There was this shortage and then we gave them everything we could – I don’t know they can claim credit.” The preexisting salmon-tone scarcity was mostly down to the Covid-19 pandemic and damage caused to Rosco’s production facility during the blizzard and blackouts that afflicted Texas in 2021. Zoonotic spillover and extreme weather – it was the climate crisis all along! Now that’s cleared up, perhaps we could focus on the true mystery: who is responsible for using up the world’s supply of glitter?

Fundacja BRDA opens a window of hope for rebuilding Ukraine (image: Taran Wilkhu via Dezeen).

A clear purpose

It bears repeating: awards in design (as in most fields) are just a bit of silly fun, and nobody should read too much into one project winning over any other. Nevertheless, Disegno was very happy to learn late last week that Poetics of Necessity, Poland’s contribution to the London Design Biennale, had claimed the festival’s medal for “the most outstanding overall contribution”. The pavilion displays the work of Fundacja BRDA, a Polish non-profit that has collected some 12,000 windows that it plans to donate to aid rebuilding efforts in Ukraine. Windows in Ukraine are the building elements most vulnerable to Russian shelling, while also being hard to replace given that Ukraine’s pre-war supply of glass came through Russia. The project has not only sourced windows from across Poland, but also produced a DIY manual setting out multiple alternatives for how they can be installed in damaged buildings, regardless of their size and shape and the corresponding gap in a wall. Fundacja BRDA worked with Warsaw architecture firm TŁO on the London display, which features the windows on pallets ahead of being shipped to Ukraine, and this in itself is an interesting response to the biennale format. Pavilions at biennales frequently raise profound sociopolitical questions, but it is sometimes difficult to understand how precisely these issues are being engaged with within the context of festivals that are often commercial or celebratory in tone. In the case of the Polish pavilion, there is a well-defined rationale for the display: Fundacja BRDA is hoping to use the display to raise awareness and collect further windows from the UK. If the biennale had to pick a winner, then it has, at least, chosen exceptionally wisely.

Lina Ghotmeh’s 2023 Serpentine Pavilion is a posh park café (image: Iwan Baan).

Opinions tabled

It’s finally summer, which means it’s time for the Serpentine pavilion and the annual sharpening of architecture critic’s pencils. This year it’s the turn of Lina Ghotmeh, who has created a circular pavilion titled À Table with a concept based around communal eating. Commercial tie-ins abound, with tables and stools designed in collaboration with The Conran Shop and food supplied by underwhelming chain restaurant Benugo. Ghotmeh’s original design involved glazed panels that would support the zig-zag roof, but these had to be swapped with CNC-cut plywood panels for cost and carbon calculations. The effect prompted The Guardian’s architecture critic Olly Wainwright to say it gave the structure “the look of a clumsy piece of flat-pack furniture, with the twee style of something you might find on Etsy,” which seems a little harsh given that keeping on budget is important for a project that is funded only afterwards, by the sale of the pavilion to a private buyer. As Wainwright rightly highlights, however, many previous Serpentine pavilions languish disassembled in the collections of the superrich, rather than being repurposed for the good of the community. Art Review sent food writer Ruby Tandoh down to interrogate the central conceit of Ghotmeh’s design, and was underwhelmed by the collaboration with Benugo and the blunt commercial energy it brings to the space. “The pavilion ought to be an architecturally significant work reluctantly incorporating a Benugo,” writes Tandoh. “Instead, it has become a Benugo reluctantly incorporating an architecturally significant work.” À Table opens to the public today (9 June) so if you can get to Kensington Gardens you can judge for yourself – just maybe bring a packed lunch.

Satoshi Kuwata is the winner of the newly boosted LVMH Prize for Young Designers (image: LVMH).

Power and prizes

Yes, we did say prizes in design risk straying towards silly fun. That is, unless you put some decent cash and industry heft behind them. It’s no surprise then that the announcement of a winner of the all-powerful LVMH Prize for Young Designers is notable, often hinting at the fashion industry’s future bent. This week, the award went to Satoshi Kuwata of Setchu, who is bestowed a €400,000 grant and year-long mentorship along with the prize. The Japanese designer has a comprehensive training in fashion that began with training on Saville Row and study at Central Saint Martins, followed by working at brands from the North Face to Givenchy, culminating in running his own label in Milan. Awarding the prize, the jury noted the Kuwata’s successful combination of East meets West; something that Kuwata purposefully captures in the name “Setchu” or compromise (from the Japanese term “Wayo Setchu”, with “wayo” meaning West). Kuwata’s work is a deliberate and sometimes unexpected marriage of his Japanese background and self described “360 perspective” and experiences in fashion. These ideas of combination and compromise run deeper than a cross-cultural appeal; Setchu’s collection is deliberately unisex, and “interchangeability between the genders is the main focus” according to his website. The judges noted that these combinations led to “designs [that] blend great tailoring and elegance, producing collections that are both streamlined and exquisitely cut,” as summed up by Delphine Arnault, CEO of Christian Dior Couturee. Crucially, this year the prize has been increased by €100,000, with Arnault acknowledging to Vogue that the prize money "hadn’t been raised in a long time and [€400,000] really helps. The designers have a big problem of cash flow—they have to buy fabrics and pay manufacturers before being paid by wholesale.” Amongst the glitz and glamour of award ceremonies, some reflection on the practical realties of a designer’s work during economic downturns is good to see. Empty accolades abound, but money (and LVMH) will always have power.

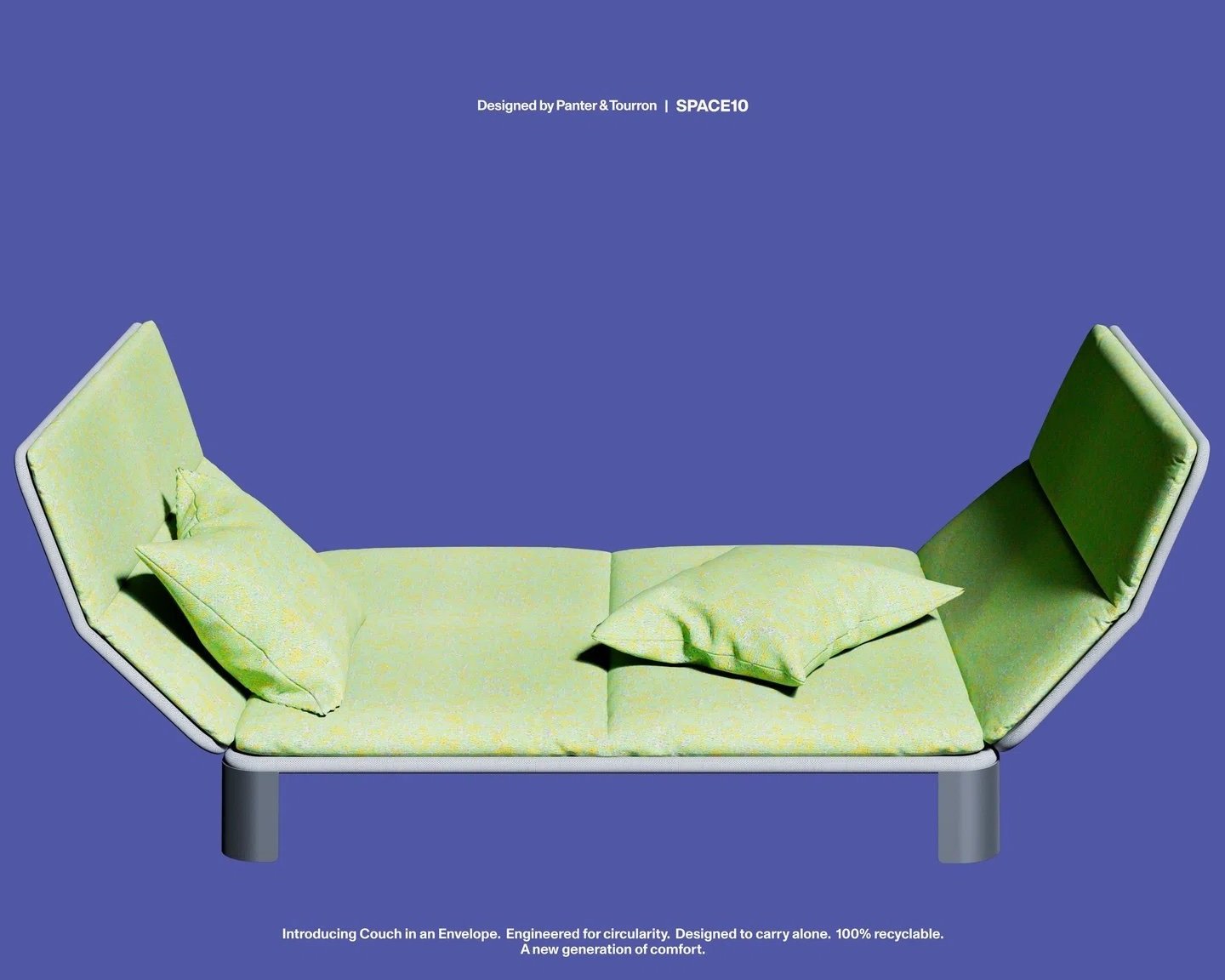

Space10 and Panter&Tourron’s concept couch is designed to weigh just 10kg (image: Space10).

Future flatpack

Space10, Ikea’s research and design lab, has been working hard on the puzzle of a flatpack sofa that could also be sustainable. As a typology, the lounge chair is notorious for being packed with foam that’s melded with the frame to make the seating extra comfy, but a complete pain in the proverbial to recycle properly (see ‘What Lies Beneath’, Disegno #29) and forces you to rely on the charity of friends when you move house. Space10 turned to design and technology studio Panter&Tourron, who used AI to try and make a lightweight and portable couch. It didn’t get off to the best start, with the AI spitting out sofas that looked just like traditional sofas. “Outdated, unsustainable design archetypes embedded in large language models are problematic in algorithms, and negatively impacting the future of design,” said Panter&Tourron founder Alexis Tourron. “Presently, AI can only take us so far in design innovation before craft, and the human hand needs to intervene.” Eventually they managed to push it in the right directions, and the result is Couch in an Envelope, a foldable sofa that is light enough for a single person to carry up a flight of stairs alone. Currently it’s just a prototype, but Space10 imagines that if it went into production the foam would be made out of mycelium and the fabric would be cellulose-based. The concept is fun and practical, but including AI in the process, however, feels like something of a gimmick. If you want to make something that breaks the mould, you clearly need a human designer at the helm.