Childhood Utopia

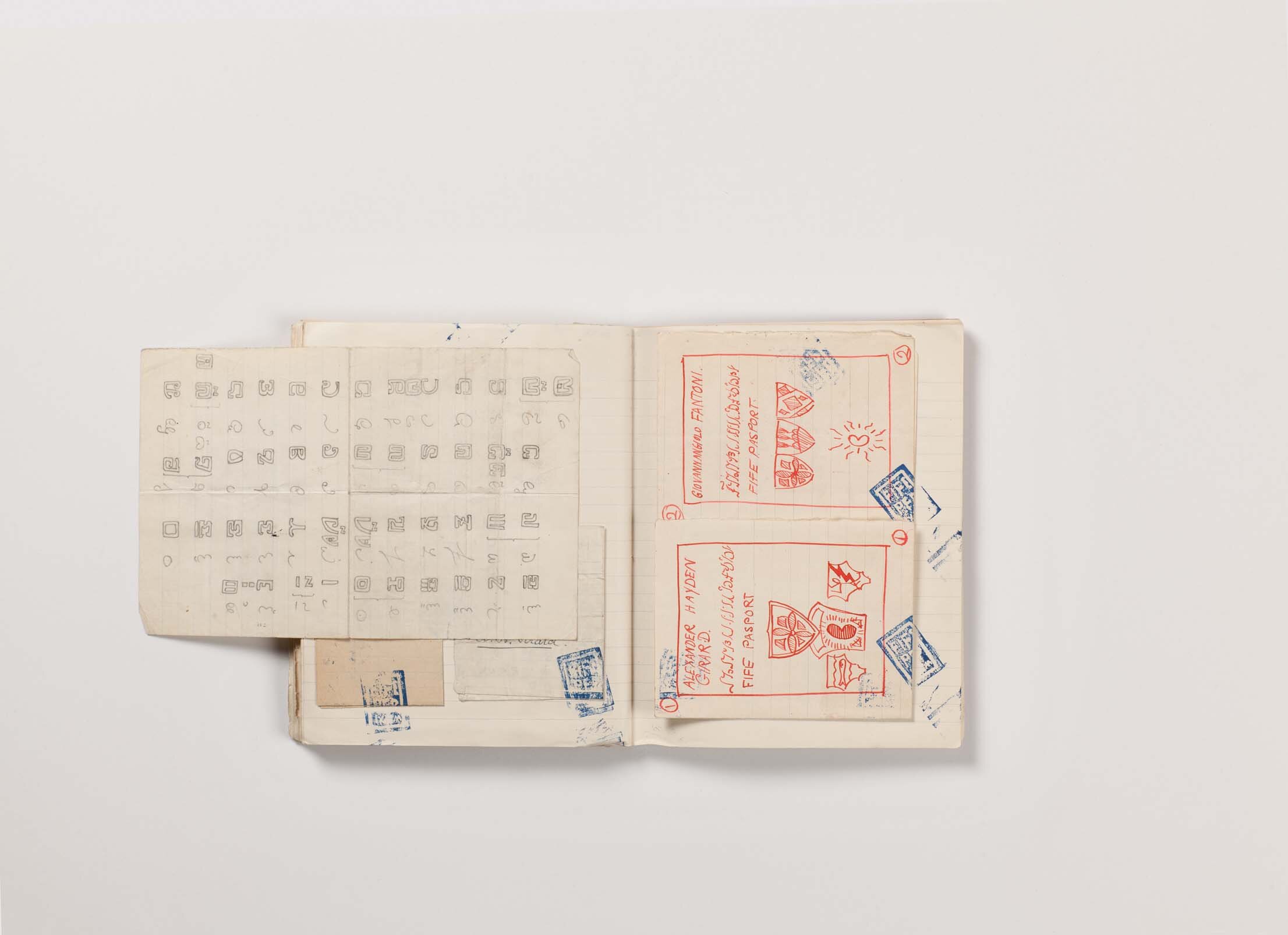

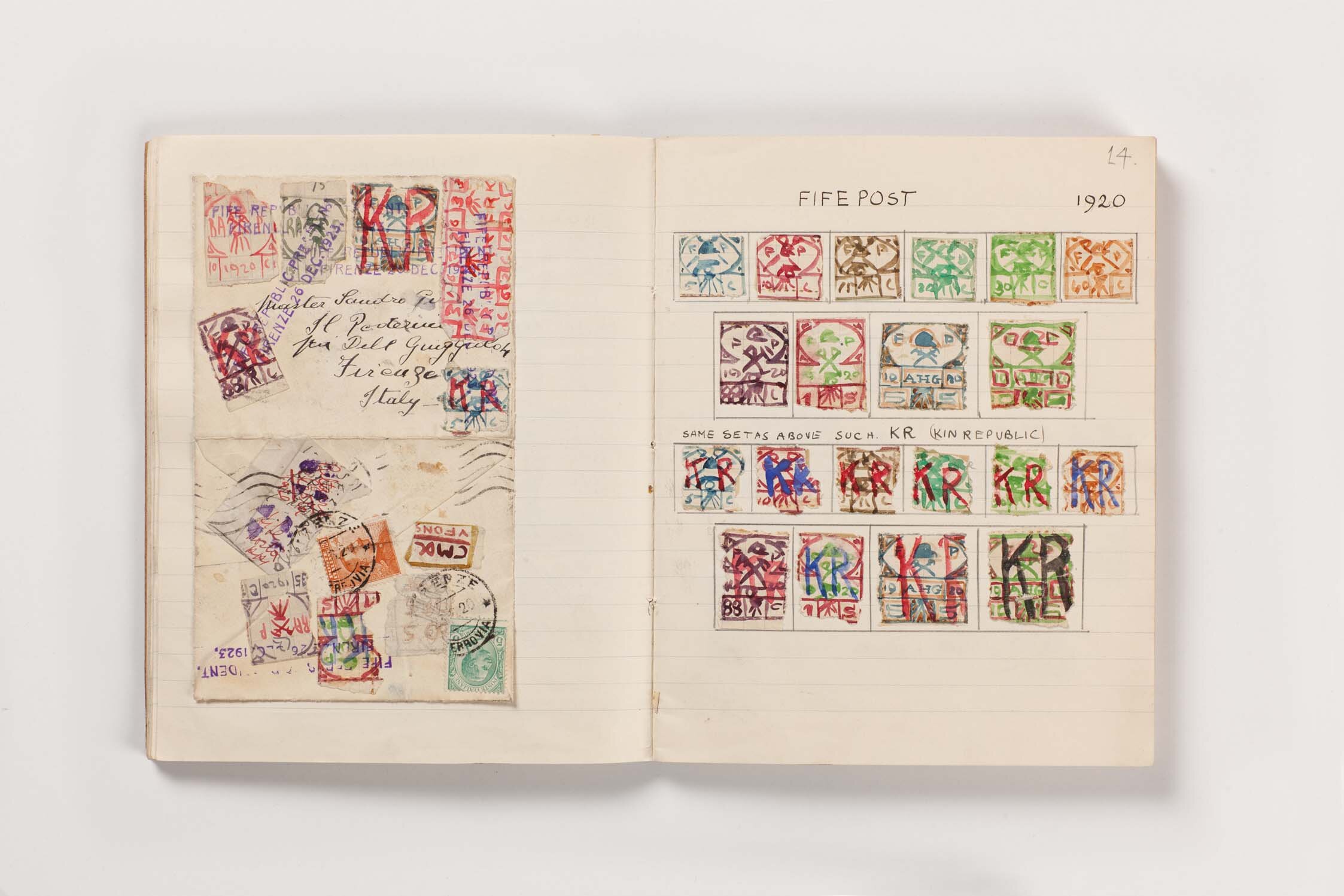

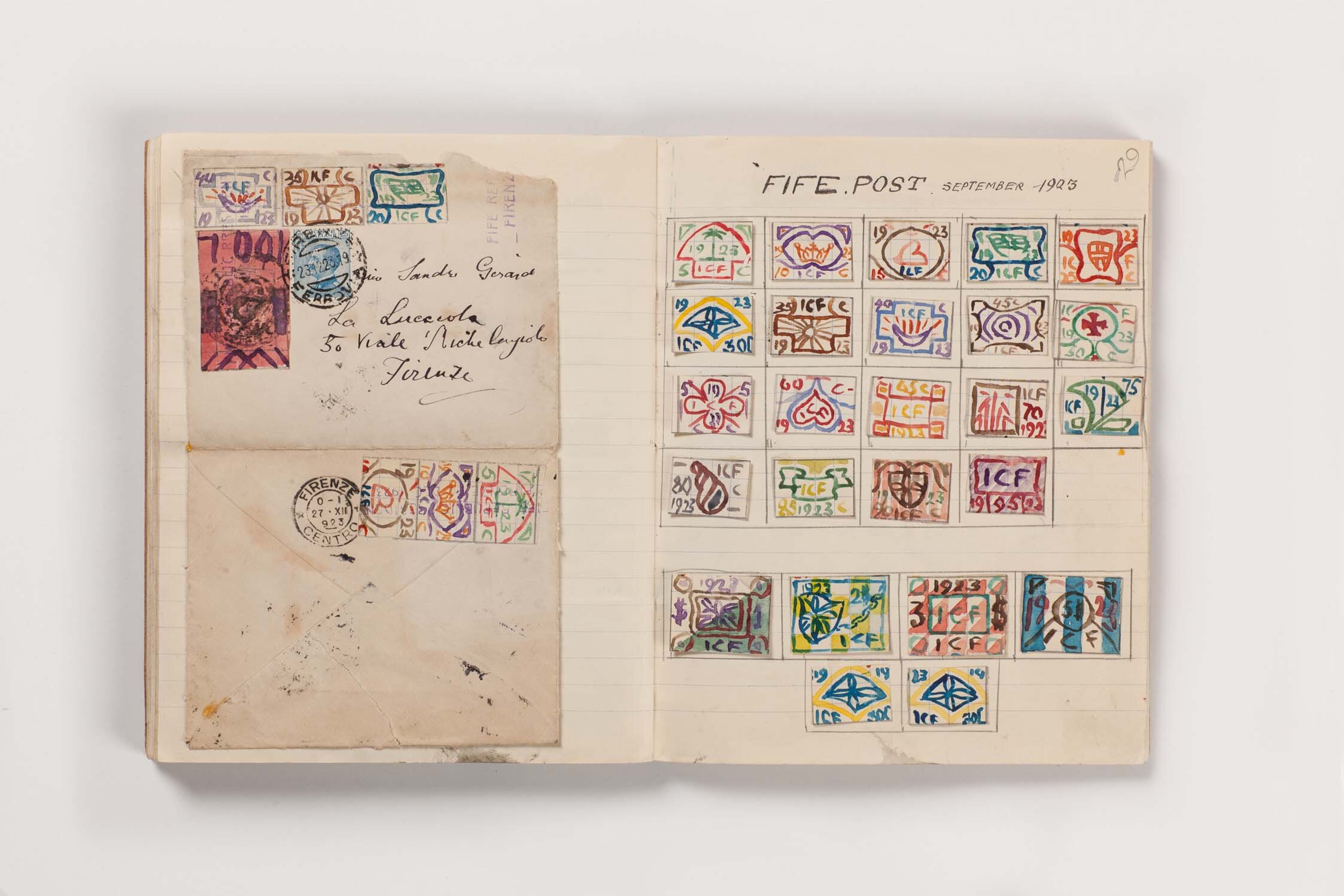

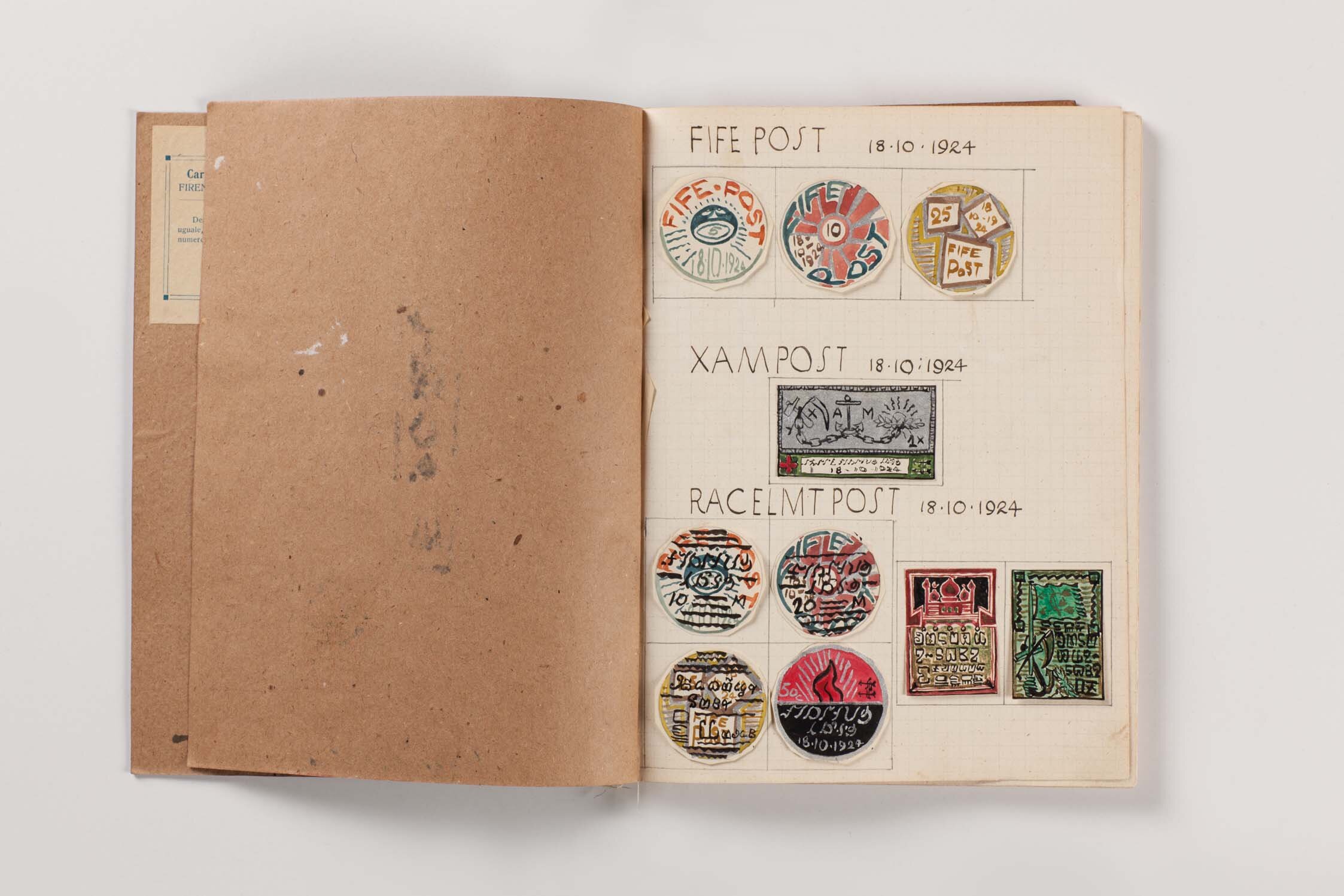

Stamps for an imaginary world designed by a young Alexander Girard (image: courtesy of Vitra Design Museum).

For Disegno’s 10th anniversary, we’re republishing 29 stories, one from each of the journal’s back issues, selected by our founder Joahnna Agerman Ross. From Disegno #13 she chose Aleishall Girard Maxon and Alexander Kori Girard’s encounter with the fantasy world that their grandfather, Alexander Girard, started designing when he was sent away to boarding school aged 10.

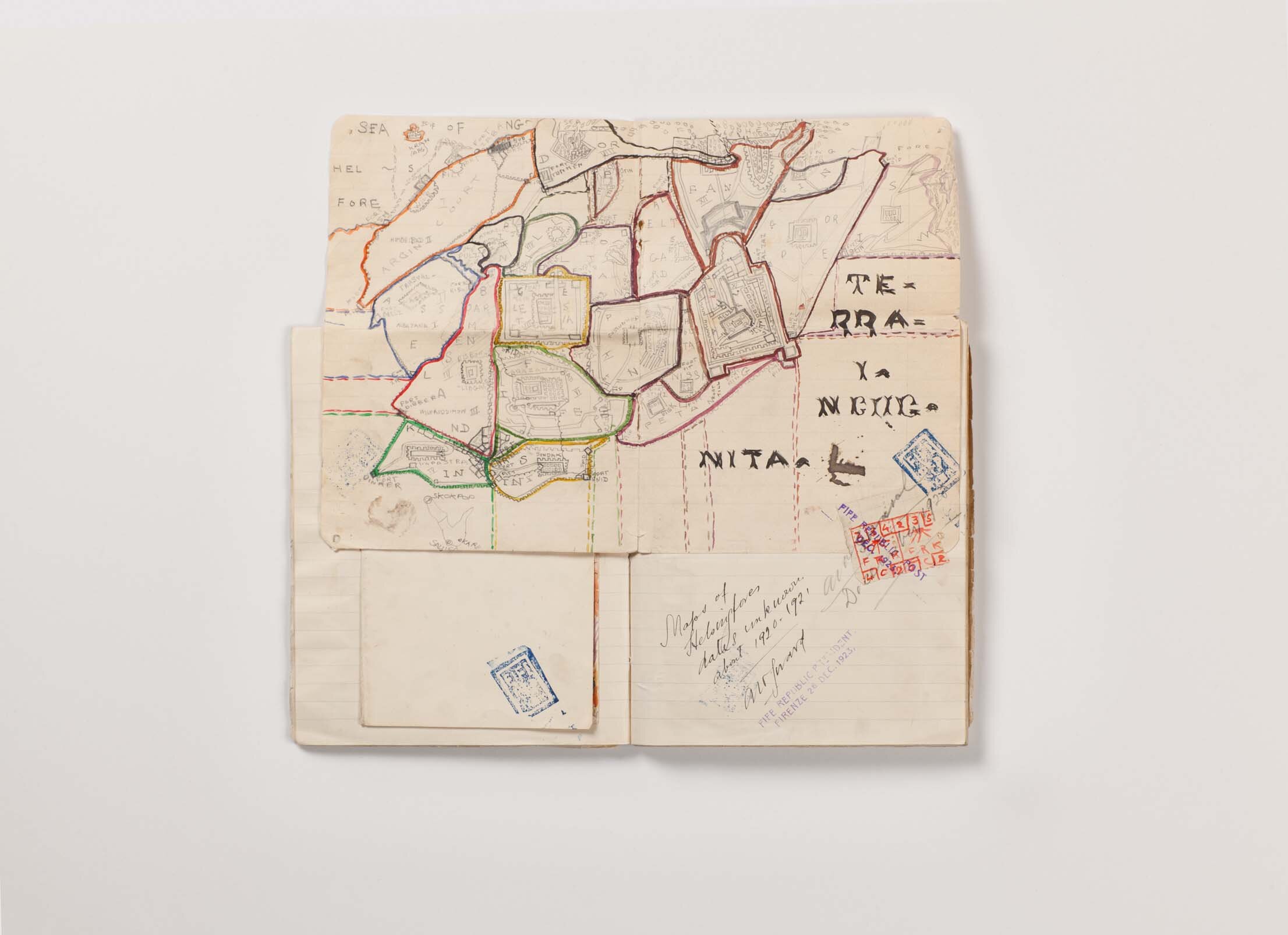

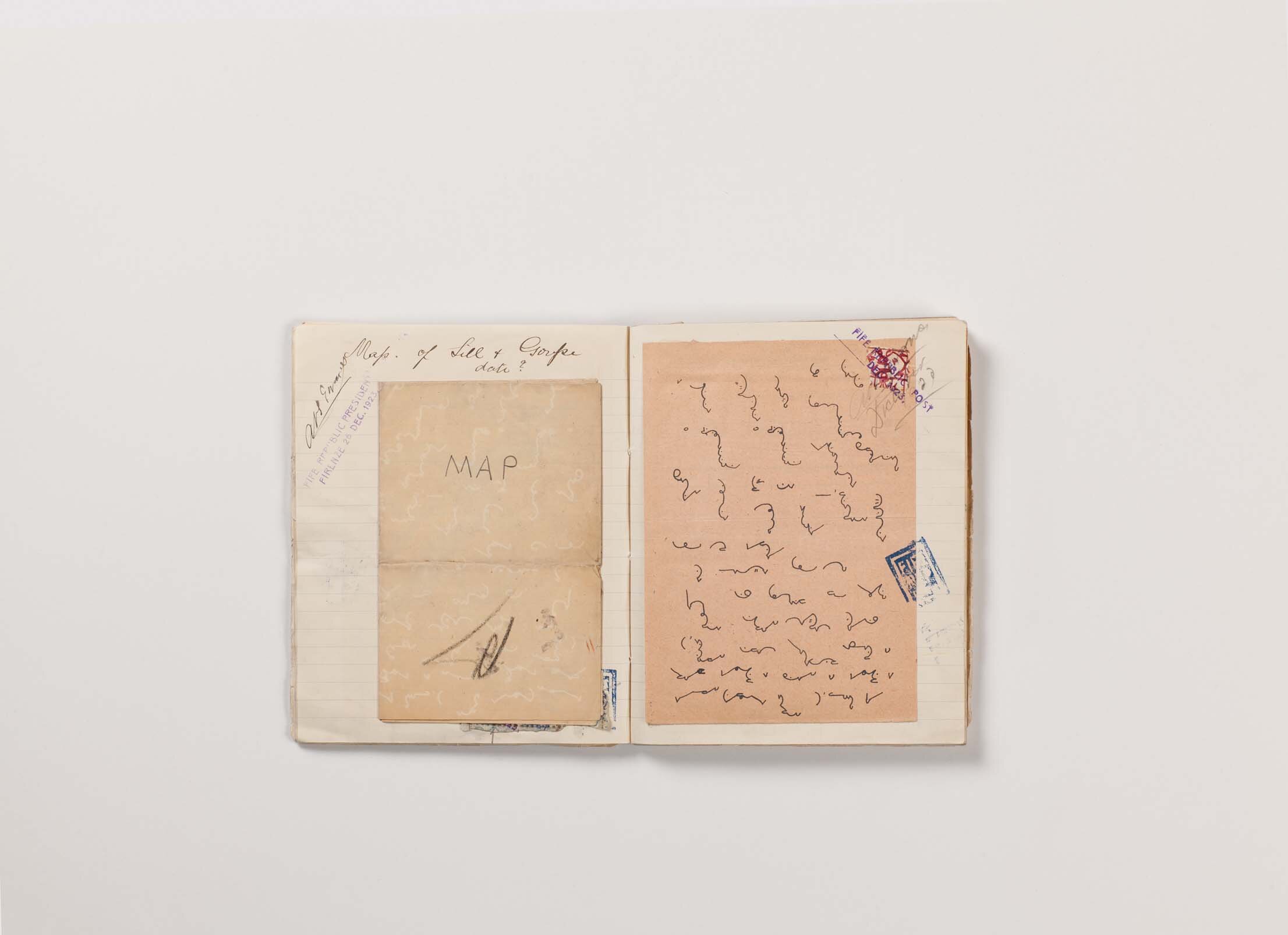

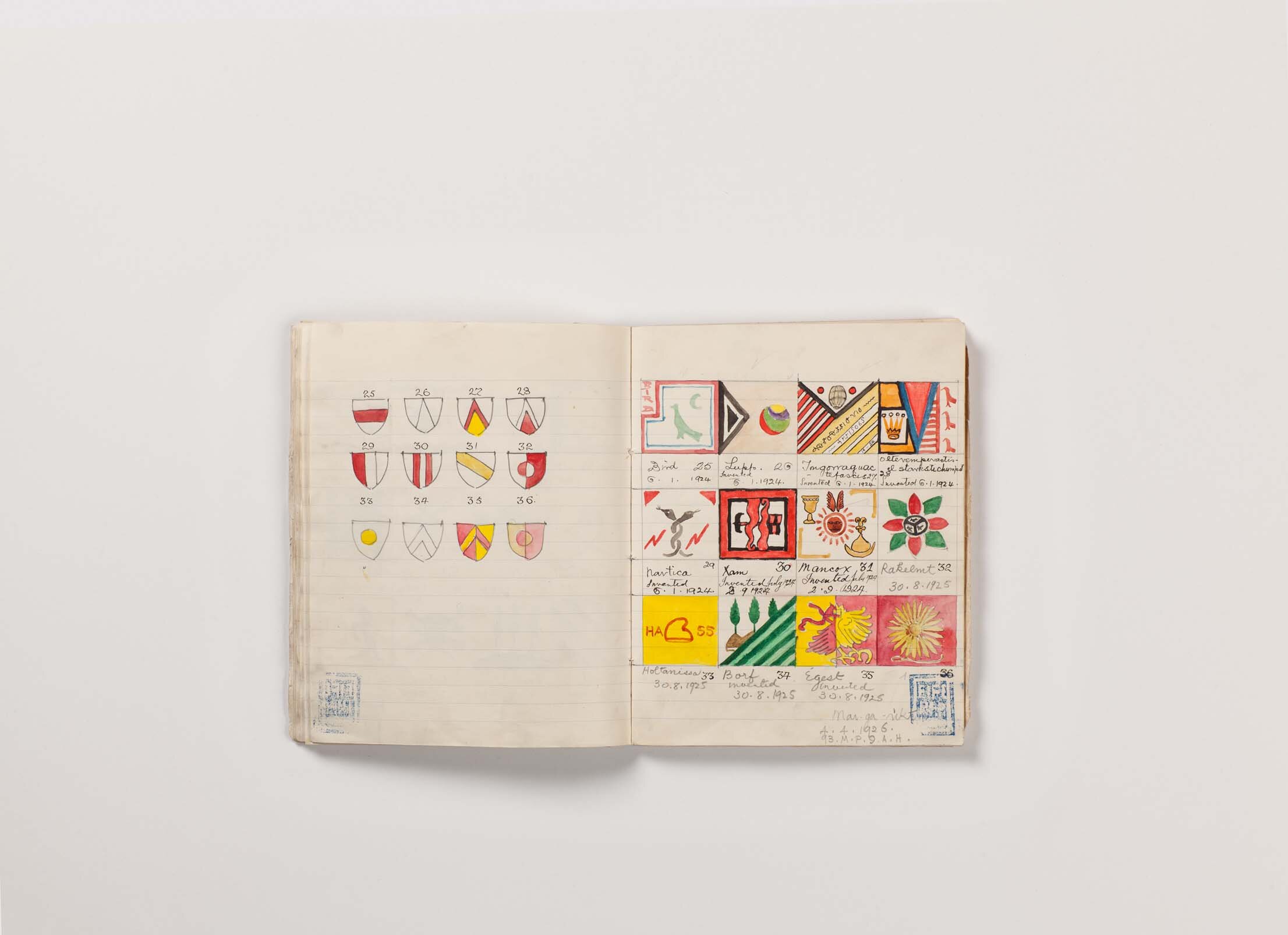

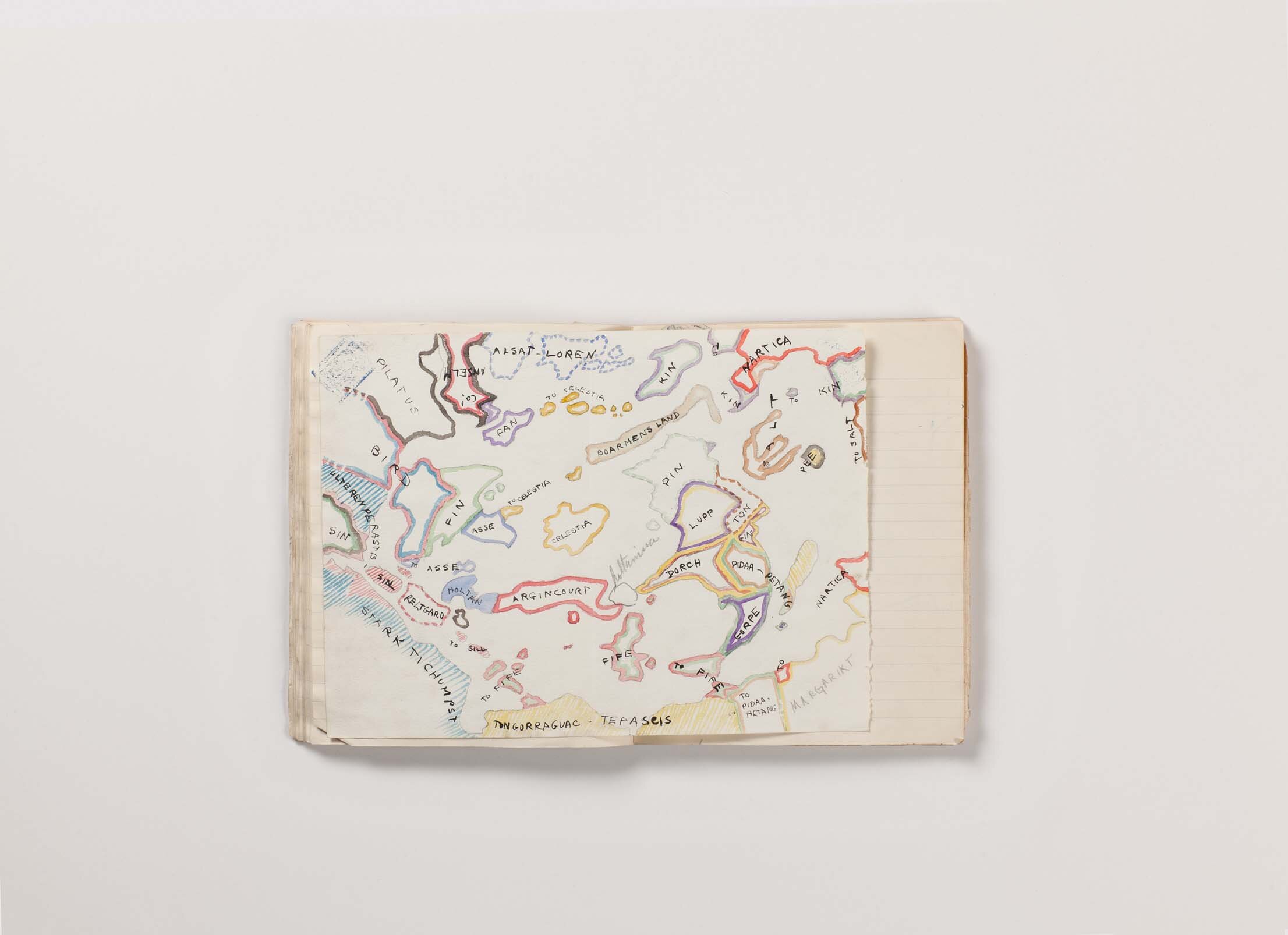

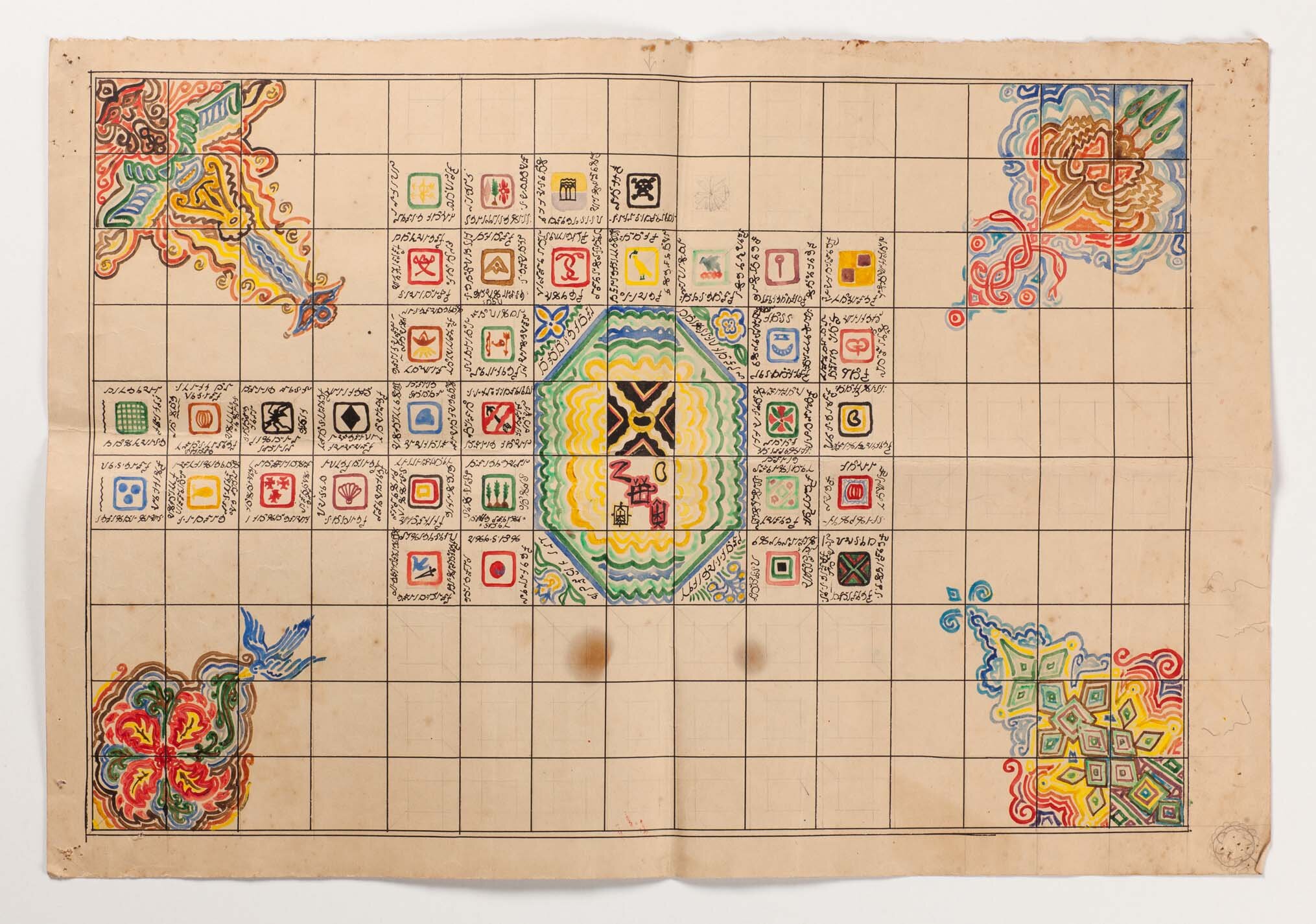

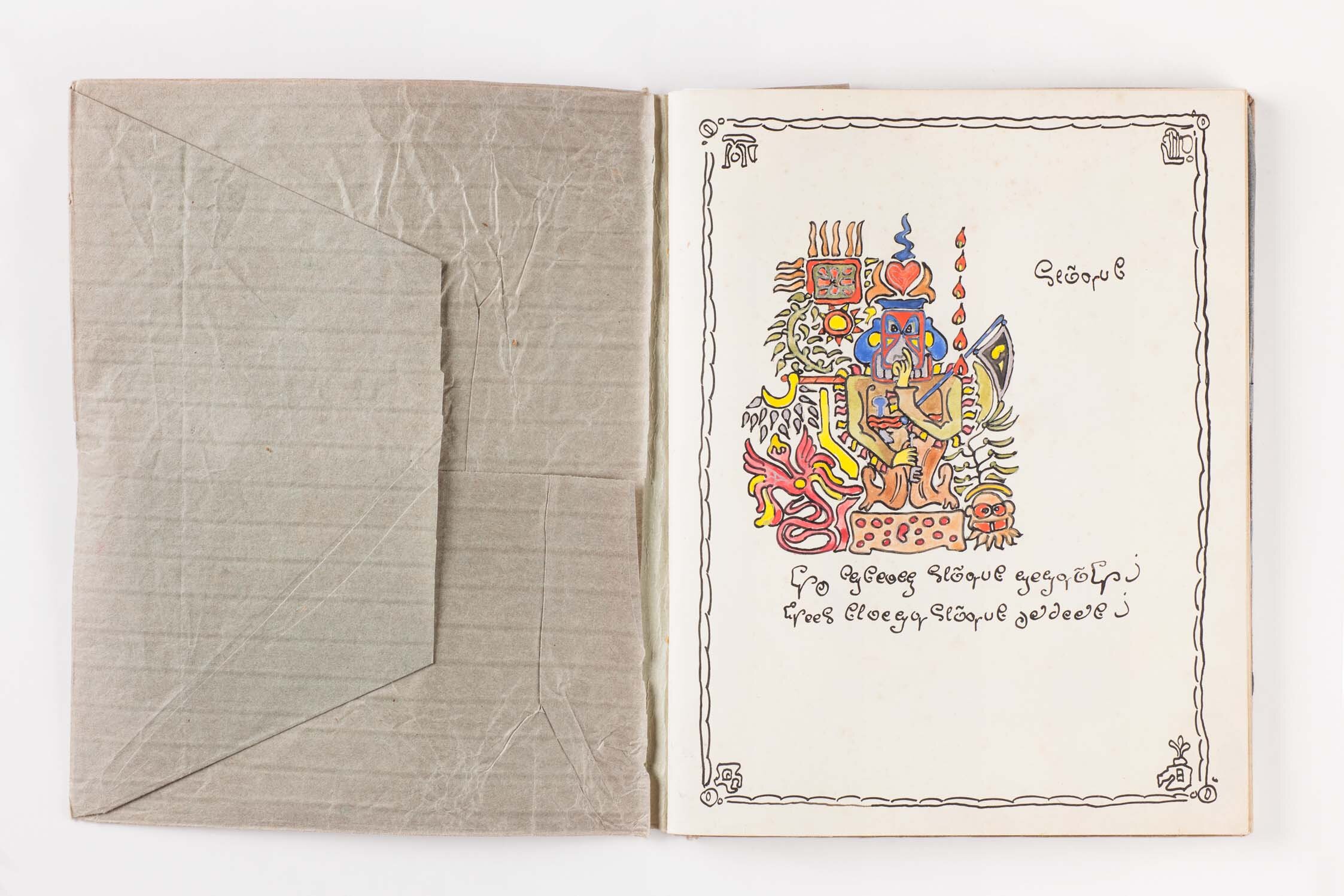

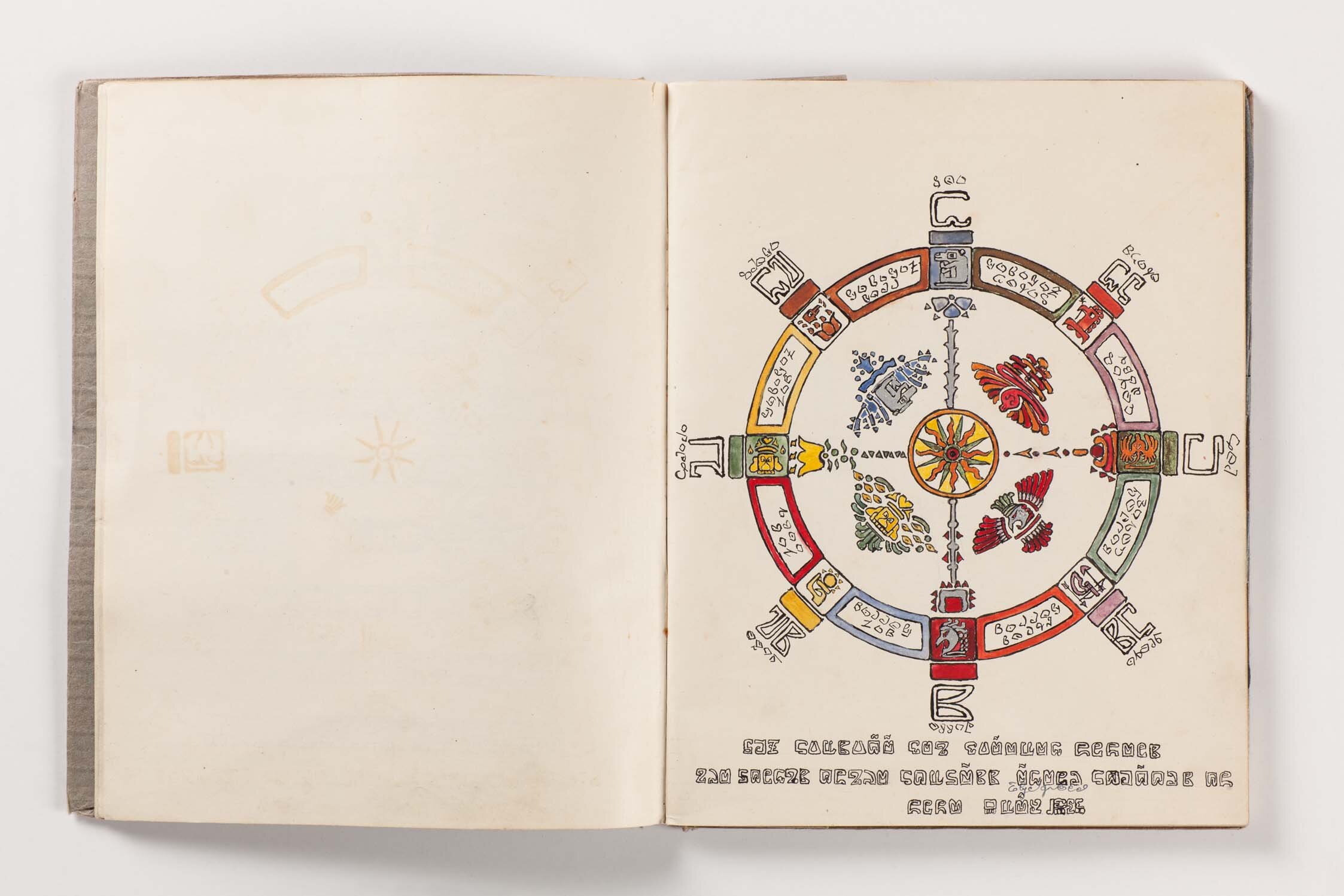

When you look through the intricate watercolour maps, carefully designed trading cards, flags, code languages and games that comprise The Republic of Fife, it is difficult to believe that this was all created by an adolescent boy, away from his home in Florence at a boarding school in England during the First World War. Alexander Girard’s childhood reverie, however, would become an incredible precursor for his later design career.

Alexander Girard (1907-1993) was one of the leading figures of postwar American design. Although known primarily for his textiles (he was head of the Herman Miller textile division for more than 20 years) he worked across architecture and interior, industrial and furniture design. Girard was also a seasoned collector, amassing what is still the largest collection of folk-art objects in the world. It eventually became The Girard Wing at The International Museum of Folk Art in New Mexico. He was also our grandfather and we knew him as a man of humour, kindness and mischief.

Young Girard designed bank notes for his make-believe world.

Growing up just minutes from our grandparents in Santa Fe, New Mexico, we were frequently in their company. We would explore their endlessly captivating home, always discovering new objects and places to hide. On occasion, we were allowed into The Foundation, a 5,000sqft concrete room built to process and house our grandfather’s collections: aluminium foil models of churches from Poland; drawers full of perfectly flattened candy wrappers; jars of stones, shells, seed pods and dirt, organised by size and colour; hotel stickers from seemingly every country in the world; an extensive array of amulets, among many other things.

“One could consider The Republic of Fife, begun in 1917, as the first comprehensive design project of our grandfather’s career.”

Discovering The Republic of Fife after our grandfather had passed away was like being transported back to those early years, when we had had free reign to explore his world. The skilled execution, refined palette and playful imagery felt familiar, while the incredible focus and distillation of the idea is astounding when you consider the complexity of the project. It spoke of his ability to see a task from every angle, addressing even the smallest of components, and his desire to use design as a means of communication. One could consider The Republic of Fife, begun in 1917, as the first comprehensive design project of our grandfather’s career. It included everything from planning and layout, to the composition of hundreds of documents and designs – flags, costumes, maps and banknotes – to support his vision for a make-believe world.

He designed costumes and flags for the fantasy land of the Republic of Fife.

Drawing on maps of Europe available at the time, our grandfather deployed his early childhood in Italy, as well as his nascent understanding of the geopolitical situation as the First World War approached – The Republic of Fife was his way of digesting the world at large. Young enough that he would not be drafted, but old enough to fear the looming danger, he sought to compose a utopia where he could affect everything from the territories to the postage stamps and all that lay between. The endeavour also connected him to his relatives, who had remained in Florence. Letters went back and forth in secret languages, demonstrating his family’s ability to honour and engage his imagination. Enlisting all of his relations, especially his younger brother Giancarlo, our grandfather honed his skill of bringing people together through correspondence, colour, design and the human need for fantasy as a coping mechanism.

“Poring over the Republic’s extensive correspondence, city plans, kingdoms, characters and cryptic symbols, it’s clear that the brothers found solace in their mystical world. ”

The relationship between our grandfather and great-uncle Giancarlo, who became a ceramic sculptor, was a deep one. The brothers were born 10 years apart and The Republic of Fife is the earliest example of their visions coming together to create a complex and calculated visual language. Although Giancarlo was young at the inception of the project, he made a huge contribution as he grew older. Poring over the Republic’s extensive correspondence, city plans, kingdoms, characters and cryptic symbols, it’s clear that the brothers found solace in their mystical world. This correspondence gave them the space to grow their relationship, despite the distance between them.

Girard drew up maps and devised a coded language

We recently experienced a number of elements from The Republic of Fife again when we visited the Vitra Design Museum’s Alexander Girard: A Designer’s Universe retrospective. We went with Aleishall’s children (aged five and eight), who brought us back to a more youthful understanding of this early work. Children’s ability to suspend disbelief and fully absorb a narrative is a trait our grandfather understood well. For Aleishall’s children, this wasn’t a fantasy or a game, but a possibility of a time and space that exists within imagination – a realm which, for children, is not yet severed from everyday life and in which they can speak and dream freely without the influence of adults. Even now, trying to decipher the exact meaning of The Republic of Fife is beyond our reach. It was a place that our grandfather created for himself and it was not intended for public consumption.

The Vitra Design Museum’s exhibition deals with only a portion of the project – the material produced between 1917 and 1924 – but the world and the languages that the Girard family developed to support it went on long after this. Much of The Republic of Fife remains a mystery for all bar those involved in its creation, but the project remains vital thanks to the beauty of its utopian impulse. Our grandfather made the seemingly unfamiliar something that we might recognise within ourselves.

Words: Aleishall Girard Maxon and Alexander Kori Girard (Girard Studio)

Images: courtesy of the Vitra Design Museum

This article was originally published in Disegno #13. To buy the issue, or subscribe to the journal, please visit the online shop.