Are We All Investors?

Image: Robinhood.

At the beginning of this year, we saw what happens when millions of small-time investors coordinate to make money, with the bonus effect of annoying Wall Street: the GameStop short squeeze.

The video game retailer GameStop was in trouble. Its asset growth rates had been in the red for several years, its equity was declining constantly, and hedge funds had begun to short the company’s stock. For those unfamiliar with the practice, shorting sees investors borrow stock in order to sell it, intending to buy it back later at a lower price before returning it to the lender – thereby making money off the difference between sell and buy price. As Gamestop’s shares (GME) fell, however, amateur investors took note of what the hedge funds were doing and began buying up the shorted stock, thus driving prices up again.

GME’s value jumped from $13.66 at the beginning of December 2020 to $347.51 by the end of January 2021. Hedge funds that had bet on the price falling were forced to buy stock back at a higher price, thus losing money on their investment. One of the funds caught in the squeeze, Melvin Capital, lost 53 per cent of the $13bn it was managing at the start of January, forcing it to take an emergency cash injection of $2.75bn from two other hedge funds. What became clear was that amateur investors could now exert enormous influence over markets which had previously been the purview of professional investors. The opening up of these secluded spaces can be linked to a significant change in the financial industry – the rising popularity of FinTech.

While app-extensions of financial services such as managing your bank account or transferring money through PayPal have been around for some time, a multitude of apps now exist with the purpose of gamifying finance and allowing amateurs access to the stock market: TD Ameritrade, eToro, Acorn, Moneybox, or E-Trade, to name a few. The disruptive potential of these trading apps lies in their personalisation of investing and the way in which they allow everyone, independent of professional background, to trade whenever, from wherever. One FinTech provider in particular, Robinhood, made headlines with its involvement in the GameStop short squeeze, serving as the platform of choice by which the amateurs, who largely organised themselves through the subreddit r/wallstreetbets, took on the professional traders.

“Millions of new investors have entered the market for the first time as technology transforms the world. It’s time for the financial system to catch up.”

Founded in 2013 by Vladimir Tenev and Baiju Prafulkumar Bhatt, Robinhood is one of the most popular (and most controversial) retail brokerage firms on the market. In a blog post from December 2020, the company reports a recent increase of “3+ million people who joined Robinhood this year”, which it attributes to the pandemic. While global lockdown may have provided many with a motivation to get their personal finances in a row, FinTech companies deliberately target tech-savvy customers with the technical know-how, financial means and confidence to trade online. In particular, they focus on millennials, who are assumed to be both digital natives and eager to maximise profits on what they’ve earned from entering the workforce. Having grown up during the economic crisis in 2008, these users may be wary of established financial institutions. Against this backdrop of generational wealth transfer and progressing digitalisation of services, Tenev and Bhatt realised that there was an underserved market to which their app could provide a solution – millennial- friendly financial inclusion. It was a vision of techno-optimism, which Tenev set out on the company’s blog. “Millions of new investors have entered the market for the first time as technology transforms the world,” he wrote. “It’s time for the financial system to catch up[...]As industry leaders, we need to meet this moment with a vision for the future and a focus on the people we serve[...] Technology is the answer, not the oft-cited impediment.”

In contrast to the image of traditional bankers, FinTech providers claim that wealth accumulation is possible for everyone, not just the professional traders we see depicted in movies like The Wolf of Wall Street. In Robinhood’s first ever television commercial, aired during the 2021 Super Bowl, the company states that “We are all investors”, underlining this message by featuring diverse individuals making emotional investments in non-traditional trading settings – a process that the company likened to financial investments in order to encourage uptake on its services. A woman colouring her hair pink, for instance, is framed as making a short-term investment; a Black-owned business opening is presented as a long-term one. When a young woman uses the app while getting her morning coffee, the narrator explains, “You don’t need to become an investor, you were born one.” The company’s name alone indicates that it likes to associate itself with ideas of social justice and the wealth transfer from rich to poor. This, however, is unique to Robinhood. Other FinTech companies have opted to align themselves with existing financial hubs, such as eToro playing on the bull as the symbol of Wall Street. What all these companies have in common, however, is that they profess to democratise finance by turning the well-known Occupy slogan, “We are the 99%”, into the promise of getting a seat at the table.

Image: eToro.

The most intimidating aspect of trading for most amateur investors is the knowledge barrier. Financial markets are notoriously complicated, but these apps claim to have got you covered with everything you might need. FinTech often incorporates features that go beyond simply facilitating investment, including providing information about market news, market data and tools for financial literacy: eToro has a podcast, while Robinhood offers a blog, and plans to introduce a learning platform soon. Amateur investors bring a more social dimension to trading, which eToro also capitalises on by marketing features that “[extend] well beyond the trading platform itself”, such as a newsfeed and its popular investor program. Robinhood, meanwhile, offers analyst ratings, features such as “people also bought” and “featured in” recommendations, and the ability to search not only for specific stocks, but also top movers in the market. All of these elements of user experience (UX) design are helpful tools for inexperienced traders to gather digestible investment tips; Robinhood’s goal is “to make investing in financial markets more affordable, more intuitive, and more fun, no matter how much experience you have (or do not have)”. The software providers’ efforts reminded me of the European Stock Market Learning competition, a scheme run by the European Savings and Retail Banking Group that simulates trading transactions for high school groups. Contrary to the high school programme, however, real money is lost and won on FinTech.

Entry barriers to these apps are shockingly low – all you need are a Wi-Fi connection and a bank account (technically, you don’t even need a smartphone, as most services have a web version), and in case you don’t want to monitor money flows between your account and the apps, they also offer to set up direct deposits, pay per cheque, or schedule auto deposits. All of this is designed to make participating in the world of finance as convenient and stress-free as possible. Robinhood has even removed the financial entry barrier that many FinTech apps still have. As its website states, there is no minimum deposit and trading is commission-free to rectify the fact that “big Wall Street firms pay effectively nothing to trade stocks, while most Americans were charged commission for every trade”. To unlock this kind of access to the markets, you just need to download the app. Robinhood’s swipe-to-trade feature makes investing convenient and the range of trade options unique to its service guarantees that everyone finds what they are looking for. Order types include market orders (activity at current market price) and conditional orders (activity when certain conditions are met, with specific types such as limit order or trailing stop order also available). Setting price alerts, recurring investments, or investing in a certain amount of money or a certain number of shares, either in stock or options, is all possible. Robinhood and Acorn, an app that lets you make micro-investments by rounding up, also allow you to buy fractional shares, reducing costs and thereby removing another barrier to entry.

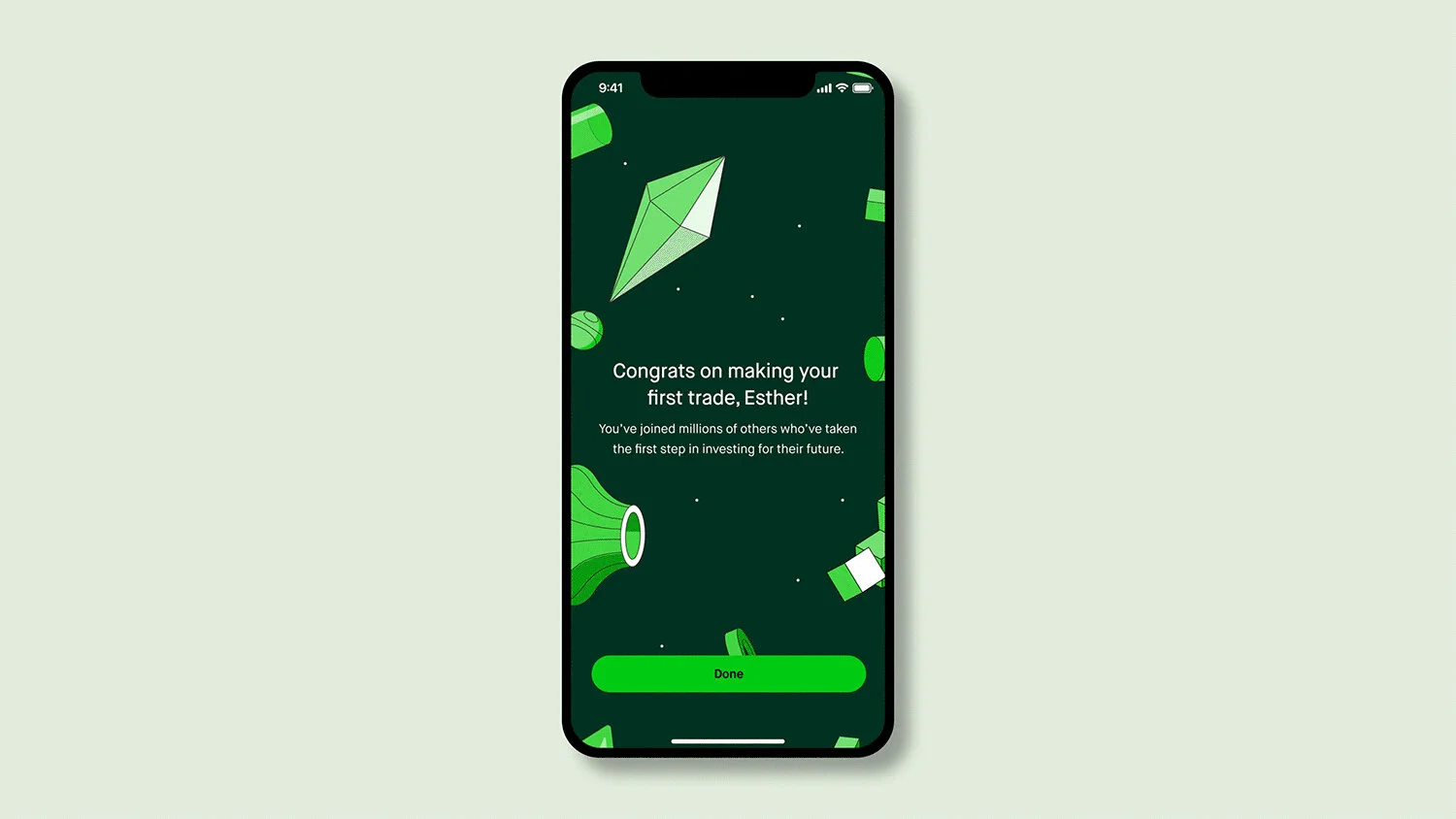

If this ease of investing paired with accessible information is not enough, Robinhood has more to motivate you to trade. New users receive some stock as a welcome-present, which makes getting started even easier, and the accompanying visual of confetti raining down the screen positively reinforces investing behaviour right from the get-go. Merging aspects of game design with elements of the trading experience is a way to make investing more engaging and enjoyable, and of drawing people back to the app. The Robinhood home screen, for instance, displays a graph with ever-changing stock values followed by daily and total returns. This illustrates at one glance what market movements mean for you, and subsequent navigation is simplified through whimsical icons, such as a wallet for viewing your investment history or a graph for the homescreen. Combined with a sleek interface, this contributes to user-friendliness, with Robinhood further allowing users to personalise its colour scheme. In the default setting, the app uses colours to signal if the stock market is open (white) or closed (black); and if investments are above (green) or below (red) market value. This gamification, the researchers Arjen van der Heide and Dominik Želinský have argued in the Journal of Cultural Economy, does not only make apps more informative, but also functions “as a means to construct highly stylized understandings of finance that reduce the ‘complexity’ of the financial world”. For its straight-forward design, Robinhood won the 2015 [app] design awards USA and the Apple Design Award in the same year.

Image: Robinhood.

It is safe to say that amateur investing is trending, but does this mean that we should all take up the opportunity to start investing on our phones? Too much techno-optimism can obscure what is at stake for amateur investors, who are trading with their own, limited resources, fuelled by idealistic online communities. On r/wallstreetbets, the online investor jcosmosstar posted during the Gamestop short squeeze: “~$70K actual loss but still diamond hands,” which is Reddit slang for investors holding stock for a collective cause regardless of risk. This shows the ease with which some users put their savings on the line and face significant losses, and the ideologies which FinTech can support. As GME stock fell in February following its meteoric rise, many investors faced substantial losses. Posting on r/wallstreetbets on 2 February, investor SimplyPwned wrote, “no sane long-term investor would consider to invest into any of these investments – this is about ‘get rich or die trying!’. This is not r/investing!”

Like most apps, FinTech also suffers from technical failures. The difference from other apps, however, is that technical failures in FinTech can cost users much more than losing their top score on Candy Crush. Nathaniel Popper, the author of Digital Gold: Bitcoin and the Inside Story of the Misfits and Millionaires Trying to Reinvent Money, explains in an article for The New York Times that “the risks of trading through the app [Robinhood] have been compounded by its tech glitches”. Known glitches include delays, which matter when market prices can change rapidly, or trouble with the execution of conditional orders. When investors do not willingly risk losses for ideological reasons, like jcosmosstar, app failures can have devastating consequences. Popper reports that one user had reported in a suicide note that he had “killed himself after he logged into the app and saw that his balance had dropped to negative $730,000. The figure was high partly because of some incomplete trades.”

There are other risks of amateur investment. The ready access to updates and news provided by FinTech apps can discourage independent research, placing a lot of weight on the curation generated by the apps’ algorithms. Algorithms are routinely used in trading, but cannot entirely replace human judgment, as the hack crash of 2013 demonstrated: a false tweet sent from a hacked Associated Press account about an attack on the White House caused the financial markets to crash as the algorithms used in trading treated it like real news. Furthermore, FinTech is in danger of oversimplification on multiple fronts: interpreting stock markets is sold as something that everyone can do, but it is not straightforward at all. While it’s true that everybody can trade, there is still a significant knowledge imbalance that is tipped in the favour of professional traders and industry insiders. Reducing confusion is good, but can also be misleading. As Van der Heide and Želinský note, it “simultaneously reinforces the boundaries between insiders and outsiders by cultivating very specific forms of financial knowledge”. Professional traders retain the upper hand with their knowledge of the market’s inner workings and ability to pore over financial reports, whereas amateurs must rely on their own judgement and the selected information that the app provides them with.

“Although it seems evident that FinTech makes finance more accessible, it is less clear whether it makes the field more democratic.”

While it may be satisfying to watch graphs rise, it is also dangerous: the allure of gamification can lead users to invest more than they had originally planned and draw those with less experience to riskier trading. Highly volatile stocks make for nice graphs and might yield big wins, but also big losses. This, however, is not accounted for by FinTech apps, which actively encourage users to invest by making it extraordinarily easy to move money. Linking an app to a bank account allows for uncomplicated transactions of large sums, while the UX also influences the perception of choices that investors have. Robinhood offers buy and sell as its only trade options, but this is not an accurate representation of the choices actually available – another important option for generating revenue is to hold. Failing to make this a clickable option, however, encourages actions that can lead to increased market volatility.

Although it seems evident that FinTech makes finance more accessible, it is less clear whether it makes the field more democratic: the interests of financial institutions remain those that are still best protected and served. When the GameStop short squeeze led to hedge funds losing huge sums, Robinhood temporarily restricted trading of GME stock. Many users spoke out against this perceived hypocrisy, dropping the app’s Google Play store rating to one star, while this critique was backed by a wide range of celebrities from Elon Musk tweeting that “shorting is a scam legal only for vestigial reasons”, to Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, on the same platform, saying, “This is unacceptable. We now need to know more about @RobinhoodApp’s decision to block retail investors from purchasing stock while hedge funds are freely able to trade the stock as they see fit. As a member of the Financial Services Cmte, I’d support a hearing if necessary.”

Image: eToro.

Robinhood defended itself by arguing that its clearing broker, the intermediary behind the app and the markets that actually handles the exchange of money and stocks, “put the restrictions in place in an effort to meet increased regulatory deposit requirements, not to help hedge funds.” Yet Robinhood’s measures ran counter to what its name suggests and eventually led to the congressional hearing that Ocasio-Cortez proposed. This is not even the first time that Robinhood has been under review by the SEC, the United States’s security and exchange commission, for its business model. The app makes its money by acting as a broker between retail investors and investment firms; in other words, it gets compensated for directing orders to these firms as part of a process called “payment of order flow”. While information about this business model can be found on Robinhood’s website, it is not immediately obvious through the app, which the SEC criticised in December 2020. In a press release, the SEC stated that a lawsuit pertaining to actions from 2015 to 2018 had been filed “for repeated misstatements that failed to disclose the firm’s receipt of payments from trading firms for routing customer orders to them, and with failing to satisfy its duty to seek the best reasonably available terms to execute customer orders.” Robinhood agreed to pay $65m to settle the charges.

The GameStop short squeeze and Robinhood’s involvement in it shows that strengths in user experience simultaneously carry weaknesses of oversimplification. FinTech can do great harm to individual amateur traders: those who are less protected by market regulations and who are more likely to trade from a precarious financial position. While the gamification of finance makes the historically elitist space of finance accessible to a wider audience, it is a double-edged sword that reinforces existing imbalances and, in the end, benefits established financial institutions most. FinTech should be treated with care. It democratises opportunity for profit and loss simultaneously.

Robinhood and eToro are both available from various app stores.

Words Anna Rohmann

This article was originally published in Disegno #29. To buy the issue, or subscribe to the journal, please visit the online shop.

RELATED LINKS